Summary

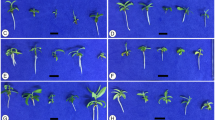

First-generation seed tubers (seedling tubers) derived from true potato seed (TPS) were produced in nursery beds; the yields were up to 12 kg and total numbers up to 1242 tubers (>1 g) per m2 of bed. Direct sowing of TPS in beds followed by thinning gave yields similar to those from transplanted seedlings and reduced the total growing period. The optimum plant population was 100 plants per m2 spaced at 10 cm×10cm. The application of 3 cm of substrate (1∶1 shredded peat moss:sand) after seedling emergence was sufficient to maximize tuber number and to minimize tuber greening. Two or three applications of N-dimethylaminosuccinamic acid (B9) gave sturdier plants but did not increase the number of tubers >1 g. The seedling tubers when multiplied gave yields similar to those of low virus clonal seed tubers.

The potential use of this method by farmers in developing countries is discussed.

Zusammenfassung

Für den Kartoffelanbau erscheint die Verwendung von Pflanzkartoffeln, die von Samenkartoffeln (TPS) stammen, als besonders geeignet, weil hier die niedrigen Kosten und der hohe Gesundheitsstandard der TPS vereinigt werden können mit der gewohnten Handhabung und der schnellen Pflanzenentwicklung bei Pflanzkartoffeln.

Die von den TPS stammenden Knollen der ersten Generation (Sämlingsknollen) wurden in Beeten von 1,1 m Breite und 0,25 m Tiefe erzeugt, die mit einer 1∶1 Mischung aus zerkleinertem Torf und Sand gefüllt waren. Ein Vergleich zwischen der direkten Aussaat der TPS in die Beete mit nachfolgendem Ausdünnen und dem Umpflanzen von Sämlingen in die Beete ergab bei der Reifeernte die gleiche Gesamtzahl an Knollen und Erträgen (Abb. 1).

Die gesamte Wachstumsperiode von der Aussaat an betrug bei der direkten Aussaatmethode 110 Tage, bei der Verpflanzungsmethode aber 125 Tage wegen des dem Umpflanzen nachfolgenden Wachstumsschocks. Die Zunahme der Pflanzenzahl erhöhte den Anteil des mit Blättern bedeckten Bodens (Abb. 2), verringerte die Überlebensrate der Pflanzen (Tabelle 1), erhöhte den Knollenertrag und die Anzahl der Knollen, die kleiner oder grösser als 1 g waren (Abb. 3) und verringerte nicht die Knollenzahl in einer der Grössenklassen (Abb. 4). Die optimale Pflanzendichte war 100 Pflanzen/m2 in Abständen von 10 cm × 10 cm; eine grössere Pflanzdichte behinderte das Anhäufeln.

Die Anwendung von 2–3 cm des 1∶1 Torf-Sandgemisches nach dem Auflaufen der Sämlinge förderte die Stolonenbildung und erhöhte die Anzahl und das Gewicht der Knollen >1 g im Vergleich zur Kontrolle (Tabelle 2). Bei der Anwendung von 6–7 cm Substrat unterschied sich die Stolonen-und Knollenbildung nur wenig von derjenigen mit 2–3 cm. Die Applikation von N-Dimethylaminobernsteinsäure (B9) ergab kräftigere Pflanzen sowie weniger und kürzere Stolonen (Tabelle 3). Die Applikation bei Pflanzenhöhen von 10 und 15 cm beeinträchtigte nicht die Knollenzahl oder den Ertrag, während Applikationen bei Pflanzenhöhen von 8, 12 und 20 cm die Anzahl der Knollen, die kleiner als 1 g sind, um 73% erhöhte und das Gesamtgewicht der Knollen, verglichen mit der Kontrolle, verringerte. Die Sämlingsknollen >1 g wurden in bewässerten Feldern mit einem durchschnittlichen Multiplikationsfaktor (Verhältnis zwischen dem gepflanzten und dem geernteten Gewicht) von 22 vermehrt. Eine 10 m2 grosse Anzuchtfläche könnte genügend Knollen erzeugen, um nach 3 aufeinanderfolgenden Vermehrungen 200 t Pflanzkartoffeln zu erhalten.

Vermehrte Sämlingsknollen der Linie DTO-33 die von offen bestäubten TPS stammten, ergaben gleiche Erträge wie die virusarmen Pflanzkartoffeln des Klones DTO-33.

Die Methode, Sämlingsknollen in Anzuchtgärten zu erzeugen, könnte die Landwirte in den Entwicklungsländern in die Lage versetzen, ihre eigenen Pflanzkartoffeln zu produzieren.

Résumé

L'utilisation de plants issus de semences vraies (TPS) semble être une méthode efficace pour la culture de la pomme de terre, car elle associe à un faible coût un niveau sanitaire élevé des semences vraies, ainsi qu'une facilité de manutention et un développement rapide des plantes à partir des tubercules de semence.

La première génération de tubercules (tubercules issus de plantules) provenant de semences vraies a été plantée en billons d'1.1 m de large et 0.25 m de profondeur, remplis d'un mélange 1∶1 de tourbe fragmentée et de sable. Un semis direct suivi d'un éclaircissage, comparé à un repiquage de plantules dans les billons, donne un nombre total de tubercules et un rendement à maturité identique (fig. 1). La période de végétation à partir du semis était de 110 jours mais atteint 125 jours avec la méthode de repiquage, à cause d'un retard de croissance après plantation. L'augmentation conduit à un recouvrement du sol plus rapide par le feuillage (fig. 2), à une diminution de la survie des plantes (tableau 1), à un rendement en tubercules plus important, à un nombre plus élevé de tubercules inférieurs ou supérieurs à 1 g (fig. 3), tandis que le nombre de tubercules par calibre ne diminue pas (fig. 4). La densité optimale est de 100 plantes par m2 espacées de 10 cm × 10 cm. Une population plus dense empêche le buttage. Un apport de 2–3 cm du mélange tourbe-sable après la levée de plantules favorise la formation des stolons et augmente le nombre et le poids des tubercules inférieurs à 1 g par rapport au témoin (tableau 2). Un apport de 6–7 cm de substrat donne peut de différence au niveau de la formation des stolons et des tubercules, par rapport à 2–3 cm. Une application d'acide N-dimethylaminosuccinamique (B9) donne des plantes plus vigoureuses et moins de stolons et de longueur plus courte (tableau 3). Une application réalisée au stade 10–15 cm des plantes n'affecte pas le nombre de tubercules ni le rendement, tandis que des applications à 8, 12 et 20 cm augmentent de 73% le nombre de petits tubercules inférieurs à 1 g et diminuent le poids total des tubercules par rapport au témoin. Les tubercules supérieurs à 1 g issus de semences sont multipliés en parcelles irriguées avec un coefficient de multiplication 22 (rapport entre poids récolté et poids planté). 10 m2 de surface de multiplication peut produire un nombre de tubercules suffisant pour atteindre 200 tonnes de plants après 3 multiplications successives.

Les tubercules obtenus par multiplication à partir de semences vraies de la lignée DTO-33 ont donné des rendements similaires à des plants indemnes de virus issus du clône DTO-33. La méthode de production de plants à partir de semences peut permettre aux producteurs des pays en voie de développement de produire leur propre plant.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Accatino, P. & P. Malagamba, 1982. Potato production from true seed. Bulletin, International Potato Center, Apartado 5969, Lima, Peru, 20 pp.

Bedi, A. S., P. Smale & D. Burrows, 1980. Experimental potato production in New Zealand from true seed. In: The International Potato Center Report of the Planning Conference on the Production of Potatoes from True Seed (Manila, Philippines): 100–116.

Devaux, A., 1984. True potato seed development. Circular, International Potato Center 12(3): 6–7.

Harris, P. M., 1983. The potential for producing root and tuber crops from seed. Sixth symposium of the International Society for Tropical Root Crops (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru, 20–25 February 1983).

Hermsen, J. G. T., 1980. Aardappelteelt uit zaden: problemen en perspectieven. Growing potatoes from seed: problems and prospects.Zaadbelangen 34: 67–72 (in Dutch).

Kunkel, R., 1980. Physiological and agronomic constraints in the use of botanical potato seed in commercial potato production. In: The International Potato Center Report of the Planning Conference on the Production of Potatoes from True seed (Manila, Philippines): 29–35.

Li, C. H. & C. P. Shen, 1980. Production of marketable and seed potatoes from botanical seed in the People's Republic of China. In: The International Potato Center Report of the Planning Conference on the Production of Potatoes From True Seed (Manila, Philippines): 21–28.

Malagamba, P., 1983. Seed-bed substrates and nutrients requirements for the production of potato seedlings. In: W. J. Hooker (Ed.), Proceedings International Congress ‘Research for the Potato in the Year 2000’ (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru): 127–128.

Martin, M. W., 1983a. Techniques for successful field seeding of true potato seed.American Potato Journal 60: 245–259.

Martin, M. W., 1983b. Field production from true seed and its use in breeding.Potato Research 26: 219–227.

Monares, A., P. Malagamba & D. Horton, 1983. Prospective systems and users for true potato seed in developing countries. In: W. J. Hooker, (Ed.), Proceedings International Congress ‘Research for the Potato in the Year 2000’ (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru): 134–136.

Sadik, S., 1980. Preliminary observations in vitro germination of potato true seed. In: The International Potato Center Report of the Planning Conference on the Production of Potatoes from True Seed (Manila, Philippines): 36–41.

Sadik, S., 1983. Potato production from true seed-Present and Future. In: W. J. Hooker (Ed.), Proceedings International Congress ‘Research for the Potato in the Year 2000’ (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru): 18–25.

Sawyer, R. L., 1979. Another ‘green revolution’: Botanical seeds.I.D.B. News 5(11): 4.

Song, B. F., 1984. Use of true potato seed in China. Circular, International Potato Center 12(2): 6–7.

Steinbauer, G. P., 1957. Interaction of temperature and moistening agents in germination and early development of potato seedlings.American Potato Journal 34: 89–93.

Wang, P. & C. Hu, 1982. In vitro mass tuberization and virus-free seed potato production in Taiwan.American Potato Journal 59: 33–37.

White, J. W. & S. Sadik, 1983. The effect of temperature on true potato seed germination. In: W. J. Hooker (Ed.), Proceedings International Congress ‘Research for the Potato in the Year 2000’ (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru): 188–189.

Wiersema, S. G., 1981. Seed tuber production from TPS.True Potato Seed Newsletter 2(2). International Potato Center, Apartado 5969, Lima, Peru.

Wiersema, S. G., 1983. Potato seed-tuber production from true seed. In: W. J. Hooker (Ed.), Proceedings International Congress ‘Research for the Potato in the Year 2000’ (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru): 186–187.

Wiersema, S. G., 1984. The production and utilization of seed tubers derived from True Potato Seed. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, England, 229 pp.

Wiersema, S. G., 1985. Production and utilization of seed tubers derived from true potato seed. In: Report of the Planning Conference on Innovative Methods for Propagating Potatoes. (International Potato Center, Lima, Peru).

Zaag, D. E. van der & D. Horton, 1983. Potato production and utilization in world perspective with special reference to the tropics and sub-tropics.Potato Research 26: 323–362.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiersema, S.G. A method of producing seed tubers from true potato seed. Potato Res 29, 225–237 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02357653

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02357653