Abstract

From the mid-1960s to around 1980, Sweden extended its family policies that provide financial and in-kind support to families with children very quickly. The benefits were closely tied to previous work experience. Thus, women born in the 1950s faced markedly different incentives when making fertility choices compared to women born only 15–20 years earlier. This paper examines the evolution of completed fertility patterns for Swedish women born in 1925–1958 and makes comparisons to women in neighbouring countries where the policies were not extended as much as in Sweden. The results suggest that the extension of the policy raised the level of fertility, shortened the spacing of births, and induced fluctuations in the period fertility rates, but it did not change the negative relationship between women’s educational level and completed fertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Sundström and Dufvander (2002), who show that the fraction of paid days used by fathers never exceeded 11% over the 1974–1990 period. They also perform an interesting statistical analysis of the determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ use of the leave.

Because of this policy, care centres can require that a sick child be kept home instead of coming to the centre with an obvious risk for contagion.

See Hoem and Hoem (1997) for an informative account of such policy changes.

See, e.g. Angrist and Krueger (1999) for a formal presentation of the difference-in-differences approach.

See, e.g. Gustafsson (2001).

Monthly data through December 2003 show that the recovery has continued, and seasonally adjusted figures in the fall of 2003 reached around 1.75.

Data for Denmark and the Netherlands, available from the author upon request, show the same pattern.

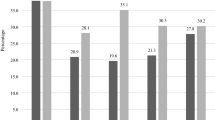

For Sweden one can see some reduction in the differentials by education level through the early 1950s, followed by some increase again during the rest of the 1950s. A very detailed analysis might find that the association between education level and completed fertility level has changed over time. Such a more detailed analysis would have to consider that the length of the educational levels have changed over time as well. My only claim in this paper is that the introduction of an extensive family policy has not eliminated the negative association between completed fertility and education level.

References

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1999) Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3A. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Birg H, Filip D, Flöthmann E-J (1990) Paritätsspezifische Kohortenanalyse des generativen Verhaltens in der Bundesrepuplik Deutschland nach dem 2. Welkrieg. IBS-Materialen Nr. 30. Institut für Bevölkerungsforschung und Sozialpolitik, Universität Bielefeld, Bielefeld

Bosveld W (1996) The aging of fertility in Europe. A comparative demographic-analytic study, PDOD. Thesis, Amsterdam

Brunborg H, Mamelund S-E (1994) Kohort-og periodefruktbarhet i Norge 1820–1993. Rapporter 94/27 SSB, Oslo

Council of Europe (2001) Recent demographic developments in Europe 2001. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Council of Europe (2003) Recent demographic developments in Europe 2003. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Daguet F (2000) L’évolution de la fécondité des générations nées de 1917 à 1949: analyse par rang de naissance et niveau de diplôme. Population 2000(6):1021–1034

Ermisch J (1989) Purchased child care, optimal family size and mother’s employment. J Popul Econ 2:79–102

Gauthier AH (1996) The state and the family: a comparative analysis of family policies in industrialised countries. Clarendon, Oxford

Gustafsson S (2001) Optimal age at motherhood. Theoretical and empirical considerations on postponement of maternity in Europe. J Popul Econ 14:225–247

Heckman J, Walker J (1990) The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: evidence from Swedish longitudinal data. Econometrica 58:1411–1441

Hoem JM (1993) Public policy as the fuel of fertility. Acta Sociol 36:19–31

Hoem B, Hoem JM (1997) Sweden’s family policies and roller-coaster fertility. J Popul Problems 52:1–22

Hotz VJ, Klerman JA, Willis RJ (1997) The economics of fertility in developed countries. In: Rosenzweig MR, Stark O (eds) Handbook of population and family economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Klevmarken A (1993) Demographics and the dynamics of earnings. J Popul Econ 6:105–122

Lappegård T (2000) New fertility trends in Norway. Demographic Research, vol 2/3. http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol2/3

Rönsen M, Sundström M (2002) Family policy and after-birth employment among new mothers—a comparison of Finland, Norway and Sweden. Eur J Popul 18:121–152

Sainsbury D (1996) Gender equality and welfare states. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schultz TP (2001) The fertility transition: economic explanations. In Smelser NJ, Baltes PB (eds) International encyclopedia of the social sciences. Elsevier, Oxford

SOU (1989) Arbetstid och välfärd. Betänkande av arbetstidskommittén. SOU 1989:53

Sundström M, Dufvander A-Z (2002) Family division of child care and the sharing of parental leave among new parents in Sweden. Eur Sociol Rev 18(4):433–447

Walker JR (1995) The effect of public policies on recent Swedish fertility behavior. J Popul Econ 8:223–251

Wennemo I (1994) Sharing the costs of children. Dissertation series no. 25, Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm

Acknowledgements

This is a revised and updated version of my presidential address at the ESPE-2001 meetings in Athens. I am grateful to several national experts for help and advice with data collection for this paper. By country, these are Belgium, Ron Lesthaeghe; Denmark, Lisbeth Knudsen, Jørn Korsbø Petersen and Nina Smith; France, Fabienne Daguet; Germany, Michaela Kreyenfeld and Thorsten Schneider; Netherlands, Gijs Beets and Jan Latten; Norway, Helge Brunnborg and Trude Lappegård; and Sweden, Gun Alm-Stenflo and Elisabeth Landgren-Möller. I also thank Gunnar Andersson, Thomas Aronsson, Lena Edlund, Jan Hoem, Per Molander, Marianne Sundström, and Mårten Palme for many valuable discussions about the paper’s topics. Three referees provided most valuable comments. Despite all help and suggestions, the usual disclaimer applies. Swedish Council for Social Research and Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research provided financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data sources

Figure 1. Data for Sweden were obtained from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers. Only women born in Sweden are included. Data for other countries were obtained from Council of Europe (2001). Births through age 42 are recorded.

Figure 3. For Belgium, data were obtained from census-based data in table A9.3 in Monografie nr. 5B (2000) Ministerie van Economische Zaken. Daguet (2000), plus more detailed data provided by her, supplied the information for France. For Germany, tabulations from the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) were made for me by Torsten Schneider. For Norway, the sources were Brunborg and Mamelund (1994), Lappegård (2000), and unpublished data from Statistics Norway. Finally, for Sweden, data came from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers merged with the education register.

Figures 4, 5, and 6. Computations for Denmark were obtained from the Fertility Data Base provided by Jørn Korsbø Petersen. Daguet (2000), plus more detailed data provided by her, supplied the information for France. Data for Germany came from Birg et al. (1990) and Kreyenfeld (unpublished data). For the Netherlands, register-based estimations were provided by Jan Latten. For Norway, the sources were Brunborg and Mamelund (1994), Lappegård (2000), and special tabulations from Statistics Norway. For Sweden, data came from special tabulations from Statistics Sweden’s population registers. As for the UK (England and Wales only), data were provided by the Office of National Statistics, Birth Statistics 1999, Table 10.3.

Figure 7. Council of Europe (2003) and national statistical offices provided the data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Björklund, A. Does family policy affect fertility?. J Popul Econ 19, 3–24 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0024-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0024-0