Abstract

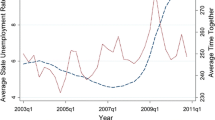

Economists have previously suggested that gains from marriage can be generated by complementarities in production (gains from specialization and exchange) or by complementarities in consumption (gains from joint consumption of household public goods and joint time consumption). This paper uses the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) from 2003 to 2011 to test whether couples that engage in less specialization (are more similar in hours of market work) spend more time together. We find that among married couples without young children, those with a greater difference in weekly hours of work between husband and wife spend less time together on non-working weekend days. Importantly, we find that this relationship is quite symmetric between couples in which the husband works greater hours and couples in which the wife works greater hours. We do not find evidence of a relationship between specialization and couple time together among couples with young children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be noted, however, that while couples that specialize do not need to enjoy each other’s company, they do need to trust each other’s commitment to the marriage. For example, a wife who doubts whether her marriage will last will be much more reluctant to specialize in household production, lowering her potential earnings in the event of divorce. To the extent that couples that are less certain of their marital stability will specialize less, this will bias us away from finding that less-specialized couples spend more time together.

Because the observed timing of work can be an artifact of how a society is organized, Hallberg (2003) tested the leisure synchronization hypothesis by constructing artificial households of single men and women for whom only societal factors should impact their time synchronization. The results indicate that the hours couples spend in the market is significantly interdependent, even after differencing out synchronization behavior that stems out from the way a society is organized.

Aguiar et al. (2013) find that the decline in market work from macroeconomic shocks results in much larger substitution into leisure than household production, but that among married couples with children there is substantial substitution into child care.

The specific question asked is “who was with you?/who accompanied you?”

For the purposes of determining the analysis sample, education-related activities are categorized as market work. An additional minor sample restriction to eliminate potential outliers is the exclusion of individuals who do not report at least 300 min of non-personal time on their time diary day.

Because we are already splitting the sample into considerably smaller subsamples, it is problematic to further estimate a separate coefficient for couples in which the wife works greater hours.

One possibility is to use the age of the oldest child as a proxy for duration of marriage. We only, however, observe age of children for those living at home, so this approach is only feasible for families with children at home. The estimates in columns 1 and 2 of Table 4 are robust to controls for the age of the oldest child at home and its square.

References

Aguiar M, Hurst E, Karabarbounis L (2013) Time use during the great recession. Am Econ Rev 103:1664–1696

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Connelly R, Kimmel J (2009) Spousal influences on parents’ non-market time choices. Rev Econ House 7:361–394

Fisher K, Egerton M, Gershuny JI, Robinson JP (2007) Gender convergence in the American heritage time-use study. Soc Indi Res 82:1–33

Hallberg D (2003) Synchronous leisure, jointness and household labor supply. Lab Econ 10:185–203

Hamermesh DS (2002) Timing, togetherness and time windfalls. J Popul Econ 15:601–623

Hamermesh DS, Frazis H, Stewart J (2005) Data watch: the American time use survey. J Econ Persp 19:221–232

Jenkins S, Osberg L (2005) Nobody to play with? The implications of leisure coordination. In: Hamermesh D S, Pfann G (eds) The economics of time use. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 113–145

Kamo Y (2000) “He said, she said”: assessing discrepancies in husbands’ and wives’ reports on the division of household labor. Soc Scien Res 29:459–476

Lam D (1988) Marriage markets and assortative mating with household public goods: theoretical results and empirical implications. J Human Resour 23:462–487

Lee YS, Waite LJ (2005) Husbands’ and wive’s time spent on housework: a comparison of measures. J Marr Fam 67:328–336

Lundberg S (2012) Personality and marital surplus. IZA J Lab Econ 1:3

Lundberg S, Rose E (1999) The determinants of specialization within marriage. University of Washington Mimeograph

Morrill MS, Pabilonia S (2012) What effects do macroeconomic conditions have on families’ time together? Discussion Paper 6529, IZA

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2007) Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. J Econ Persp 21:27–52

Sullivan O (1996) Time co-ordination, the domestic division of labour and affect relations: time-use and the enjoyment of activities within couples. Sociology 30:97–100

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments and suggestions from Brian Cadena, Craig McIntosh, and Mark Hoekstra.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Erdal Tekin

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mansour, H., McKinnish, T. Couples’ time together: complementarities in production versus complementarities in consumption. J Popul Econ 27, 1127–1144 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0510-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0510-3