Abstract

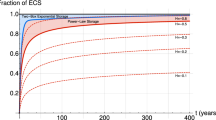

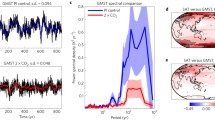

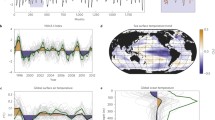

Although current global warming may have a large anthropogenic component, its quantification relies primarily on complex General Circulation Models (GCM’s) assumptions and codes; it is desirable to complement this with empirically based methodologies. Previous attempts to use the recent climate record have concentrated on “fingerprinting” or otherwise comparing the record with GCM outputs. By using CO2 radiative forcings as a linear surrogate for all anthropogenic effects we estimate the total anthropogenic warming and (effective) climate sensitivity finding: ΔT anth = 0.87 ± 0.11 K, \(\uplambda_{{2{\text{x}}{\text{CO}}_{2} ,{\text{eff}}}} = 3.08 \pm 0.58\,{\text{K}}\). These are close the IPPC AR5 values ΔT anth = 0.85 ± 0.20 K and \(\uplambda_{{2{\text{x}}{\text{CO}}_{2} }} = 1.5\!-\!4.5\,{\text{K}}\) (equilibrium) climate sensitivity and are independent of GCM models, radiative transfer calculations and emission histories. We statistically formulate the hypothesis of warming through natural variability by using centennial scale probabilities of natural fluctuations estimated using scaling, fluctuation analysis on multiproxy data. We take into account two nonclassical statistical features—long range statistical dependencies and “fat tailed” probability distributions (both of which greatly amplify the probability of extremes). Even in the most unfavourable cases, we may reject the natural variability hypothesis at confidence levels >99 %.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ammann CM, Wahl ER (2007) The importance of the geophysical context in statistical evaluations of climate reconstruction procedures. Clim Change 85:71–88. doi:10.1007/s10584-007-9276-x

Arrhenius S (1896) On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature on the ground. Philos Mag 41:237–276

Bauer S, Menon E (2012) Aerosol direct, indirect, semidirect, and surface albedo effects from sector contributions based on the IPCC AR5 emissions for preindustrial and present-day conditions. J Geophys Res (Atmos) 117. doi:10.1029/2011JD016816

Brohan P, Kennedy JJ, Harris I, Tett SFB, Jones PD (2006) Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: a new dataset from 1850. J Geophys Res 111:D12106. doi:10.1029/2005JD006548

Foster G, Rahmstorf S (2011) Global temperature evolution 1979–2010. Environ Res Lett 6:044022. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044022

Frank DC, Esper J, Raible CC, Buntgen U, Trouet V, Stocker B, Joos F (2010) Ensemble reconstruction constraints on the global carbon cycle sensitivity to climate. Nature 463(28):527–530. doi:10.1038/nature08769

Gao CG, Robock A, Ammann C (2008) Volcanic forcing of climate over the past 1500 years: and improved ice core-based index for climate models. J Geophys Res 113:D23111. doi:10.1029/2008JD010239

Hansen J et al (2005) Earth’s energy imbalance: confirmation and implications. Science 308(5727):1431–1435. doi:10.1126/science.1110252

Hansen J, Ruedy R, Sato M, Lo K (2010) Global surface temperature change. Rev Geophys 48:RG4004. doi:10.1029/2010RG000345

Huang S (2004) Merging information from different resources for new insights into climate change in the past and future. Geophys Res Lett 31:L13205. doi:10.1029/2004GL019781

Krivova NA, Balmaceda L, Solanski SK (2007) Reconstruction of solar total irradiance since 1700 from the surface magnetic field flux. Astron Astrophys 467:335–346. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066725

Lean JL, Rind DH (2008) How natural and anthropogenic influences alter global and regional surface temperatures: 1889 to 2006. Geophys Res Lett 35:L18701. doi:10.1029/2008GL034864

Ljundqvist FC (2010) A new reconstruction of temperature variability in the extra-tropical Northern Hemisphere during the last two millennia. Geogr Ann Phys Geogr 92A(3):339–351. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0459.2010.00399.x

Lovejoy S (2013) What is climate? EOS 94(1):1–2

Lovejoy S (2014) A voyage through scales, a missing quadrillion and why the climate is not what ou expect. Clim Dyn (submitted)

Lovejoy S, Schertzer D (2012a) Low frequency weather and the emergence of the climate. In: Sharma AS, Bunde A, Baker D, Dimri VP (eds) Extreme events and natural hazards: the complexity perspective. AGU monographs, pp 231–254

Lovejoy S, Schertzer D (2012b) Haar wavelets, fluctuations and structure functions: convenient choices for geophysics. Nonlinear Proc Geophys 19:1–14. doi:10.5194/npg-19-1-2012

Lovejoy S, Schertzer D (2012c) Stochastic and scaling climate sensitivities: solar, volcanic and orbital forcings. Geophys Res Lett 39:L11702. doi:10.1029/2012GL051871

Lovejoy S, Schertzer D (2013) The weather and climate: emergent laws and multifractal cascades. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lovejoy S, Scherter D, Varon D (2013a) How scaling fluctuation analyses change our view of the climate and its models (Reply to R. Pielke sr.: Interactive comment on “Do GCM’s predict the climate… or macroweather?” by S. Lovejoy et al.). Earth Syst Dyn Discuss 3:C1–C12

Lovejoy S, Schertzer D, Varon D (2013b) Do GCM’s predict the climate… or macroweather? Earth Syst Dyn 4:1–16. doi:10.5194/esd-4-1-2013

Lovejoy S, Varotsos CA, Efstathiou MN (2014) Scaling analyses of forcings and outputs of a simplified last millennium climate model. J Geophys Res (submitted, March 2014)

Lyman JM, Good SA, Gouretski VV, Ishii M, Johnson GC, Palmer MD, Smith DM, Willis JK (2010) Robust warming of the global upper ocean. Nature 465:334–337. doi:10.1038/nature09043

Mann ME, Bradley RS, Hughes MK (1998) Global-scale temperature patterns and climate forcing over the past six centuries. Nature 392:779–787

Moberg A, Sonnechkin DM, Holmgren K, Datsenko NM (2005) Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 433(7026):613–617

Muller RA, Curry J, Groom D, Jacobsen R, Perlmutter S, Rohde R, Rosenfeld A, Wickham C, Wurtele J (2013) Decadal variations in the global atmospheric land temperatures. J Geophys Res Atmos 118(11):5280–5286

Myhre G (2009) Consistency between satellite-derived and modeled estimates of the direct aerosol effect. Science 325(5937):187–190. doi:10.1126/science.1174461

Myhre G, Myhre A, Stordal F (2001) Historical evolution of radiative forcing of climate. Atmos Environ 35:2361–2373

Peng C-K, Buldyrev SV, Havlin S, Simons M, Stanley HE, Goldberger AL (1994) Mosaic organisation of DNA nucleotides. Phys Rev E 49:1685–1689

Peterson TC, Vose RS (1997) An overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network temperature database. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 78:2837–2849. doi:10.1175/1520-0477

Rayner NA, Brohan P, Parker DE, Folland CK, Kennedy JJ, Vanicek M, Ansell T, Tett SFB (2006) Improved analyses of changes and uncertainties in marine temperature measured in situ since the mid-nineteenth century: the HadSST2 dataset. J Clim 19:446–469

Santer BD et al (2013) Identifying human influences on atmospheric temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110(1):26–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210514109

Smith E, Conception SJ, Andres R, Lurz J (2004), Historical sulfur dioxide emissions 1850–2000: methods and results report. U.S. Department of Energy

Smith TM, Reynolds RW, Peterson TC, Lawrimore J (2008) Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880–2006). J Clim 21:2283–2293

Wang Y-M, Lean JL, Sheeley NRJ (2005) Modeling the Sun’s magnetic field and irradiance since 1713. Astrophys J 625:522–538

Wigley TML, Jones PD, Raper SCB (1997) The observed global warming record: what does it tell us? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:8314–8320

Acknowledgments

P. Dubé, the president of the Quebec Skeptical Society, is thanked for helping to motivate this work. An anonymous reviewer of an earlier version of this paper is thanked for the opinion that a GCM free approach to anthropogenic warming cannot work, concluding: “go get your own GCM”.This work was unfunded, there were no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Scaling modified Gaussians with fat tails

Appendix: Scaling modified Gaussians with fat tails

In Fig. 9 we showed the empirical probability distributions (Pr(ΔT > s), for the probability of a random (absolute) temperature difference ΔT exceeding a threshold s for time lags Δt increasing by factors of 2. Note that we loosely use the expression “distribution function” to mean Pr(ΔT > s). This is related to the more usual “cumulative distribution function” (CDF) by: CDF = Pr(ΔT < s) so that Pr(ΔT > s) = 1 − CDF. Two aspects of Fig. 9 are significant; the first is their near scaling with lag Δt: the shapes change little, this is the type of scaling expected for a monofractal “simple scaling” process, i.e. one with weak multifractality (as discussed in Lovejoy and Schertzer (2013), over these time scales, the parameter characterizing the intermittency near the mean, C 1 ≈ 0.02 so that this is a reasonable approximation).

This implies that there is a nondimensional distribution function P(s):

σΔt is the standard deviation. Due to the temporal scaling, we have \(\upsigma_{{{\lambda \varDelta }t}} =\uplambda^{H}\upsigma_{{\Delta t}}\) where H is the fluctuation exponent and P(s) is independent of time lag Δt. From Fig. 9 it may be seen that as predicted by the RMS fluctuations (σΔt, Fig. 7), H ≈ 0. This is a consequence of the slight decrease in the RMS Haar fluctuation (with exponent H Haar ≈−0.1; Fig. 8). Unlike the Haar fluctuation, the ensemble mean RMS differences cannot decrease but simply remains constant until the Haar fluctuations begin to increase again in the climate regime (compare Figs. 7, 8, beyond Δt ≈ 125 years).

The second point to note is that the lag invariant distribution function P(s) has roughly a Gaussian shape for small s, whereas for large enough s, it is nearly algebraic. This can be simply modelled as:

where P G (s) is the cumulative distribution function for the absolute value of a unit Gaussian random variable. The simple way of determining s qD used here is to define s qD as the point at which the logarithmic derivative of P G is equal to −q D so that the plot of log P qD versus log s is continuous:

this is an implicit equation for the transition point s qD .

In actual fact the only part of the model that is used for the statistical tests is the extreme large s “tail” which Fig. 9 empirically shows could be bracketed between:

(with qD1 = 6, qD2 = 4) hence the Gaussian part of the model is not very important, it only serves to determine the transition point s qD . In any case, for the extremes we can see from the figure that this bracketing is apparently quite well respected by the empirical distributions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lovejoy, S. Scaling fluctuation analysis and statistical hypothesis testing of anthropogenic warming. Clim Dyn 42, 2339–2351 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2128-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2128-2