Abstract

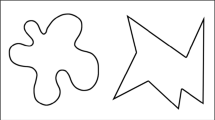

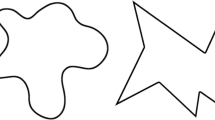

We examine a high-profile phenomenon known as the bouba–kiki effect, in which non-word names are assigned to abstract shapes in systematic ways (e.g. rounded shapes are preferentially labelled bouba over kiki). In a detailed evaluation of the literature, we show that most accounts of the effect point to predominantly or entirely iconic cross-sensory mappings between acoustic or articulatory properties of sound and shape as the mechanism underlying the effect. However, these accounts have tended to confound the acoustic or articulatory properties of non-words with another fundamental property: their written form. We compare traditional accounts of direct audio or articulatory-visual mapping with an account in which the effect is heavily influenced by matching between the shapes of graphemes and the abstract shape targets. The results of our two studies suggest that the dominant mechanism underlying the effect for literate subjects is matching based on aligning letter curvature and shape roundedness (i.e. non-words with curved letters are matched to round shapes). We show that letter curvature is strong enough to significantly influence word–shape associations even in auditory tasks, where written word forms are never presented to participants. However, we also find an additional phonological influence in that voiced sounds are preferentially linked with rounded shapes, although this arises only in a purely auditory word–shape association task. We conclude that many previous investigations of the bouba–kiki effect may not have given appropriate consideration or weight to the influence of orthography among literate subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The limitations on our materials in terms of voicing, orthography, and use of English phonemes creates a third contrast: that between stop (k, t, g, d) and continuant (s, f, z, v) consonants. This means that our items are stretched across all possible contrasts, and may make results difficult to interpret. The ideal remedy to this would be to test voiced/voiceless pairs of curved and angular stops and continuants. However, the constraints of English phonology and orthography prevent this: there are no voiced angular stops and no voiceless angular continuants in English. We address this issue more specifically in the results of each study, by looking at the specific rank of ratings for each pair of items combined with specific predictions informed by earlier results.

For all p values reported in both experiments, we provide corrected p values (unless otherwise noted) using conservative sequential Bonferroni correction (Cramer et al., 2014), given both the use of multiple post hoc ANOVAs to explore effects of stop/continuant status and the general use of multi-way ANOVAs.

Due to the fully crossed nature of our items, constrained by facts of English phonology and orthography described in the materials section, we also made post hoc analyses using two additional ANOVAs: one where stop/continuant status was included in lieu of voicing (shape × orthography × stop/continuant) and one in which stop/continuant status was included in lieu of orthography (shape × voicing × stop/continuant). A four-way model, shape × stop/continuant status × voicing × orthography, is impractical in this case since this model would result in eight cells, and we have only six types of items (two shapes, two letter shape types, two sound types). The results observed in the original ANOVA were straightforwardly replicated [significant interaction of shape × orthography, F(1, 292) = 671.28, p < 0.001; \(\eta_{p}^{2}\) = 0.509], and no additional significant interactions or effects emerged (all F’s < 1; p > 0.05). Replacing orthography with stop/continuant status (2 × 2 × 2; shape × voicing × stop/continuant status) did result in a significant three-way interaction of shape, voicing, and stop/continuant status [F(1, 292) = 671.28, p < 0.001], since crossing voicing and stop/continuant status results in divisions in orthography. Unsurprisingly, this interaction accounts for the same amount of variance explained by orthography in the other models (\(\eta_{p}^{2}\) = 0.509).

As with Experiment 1, all reported p values are corrected due to multiple post hoc ANOVAS.

As in the first experiment, we ran two additional ANOVA analyses to explore effects of stop/continuant status on shape–word ratings: one which excluded voicing in favour of stop/continuant status (shape × stop/continuant × orthography) and one which excluded orthography in favour of stop/continuant status (shape × voicing × stop/continuant; model 2c. In this case, these additional analyses presented with slightly more complicated results due to effects of voicing. Where voicing was excluded, the interaction between shape and orthography reported in the main ANOVA remained [F (1, 257) = 113.87, p < 0.001], and the voicing effect was borne out as a three-way interaction between shape, stop/continuant status, and orthography [F(1, 257) = 32.55, p < 0.001]. Where orthography was excluded, the interaction between shape and voicing remained [F(1, 257) = 32.55, p < 0.001], and the effect of orthography emerged in the form of a three-way interaction between shape, stop/continuant status, and voicing [F (1, 257) = 113.87, p < 0.001].

References

Ahlner, F., & Zlatev, J. (2010). Cross-modal iconicity: a cognitive semiotic approach to sound symbolism. Sign Systems Studies, 38(1), 298–348.

Aveyard, M. (2012). Some consonants sound curvy: effects of sound symbolism on object recognition. Memory & Cognition, 40, 83–92. doi:10.3758/s13421-011-0139-3.

Berlin, B. (1994). Evidence for pervasive synaesthetic sound symbolism in ethnozoological nomenclature. In L. Hinton, J. Nichols, & J. Ohala (Eds.), Sound symbolism (pp. 76–93). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bremner, A. J., Caparos, S., Davidoff, J., de Fockert, J., Linnell, K. J., & Spence, C. (2013). “Bouba” and “Kiki” in Namibia? A remote culture make similar shape–sound matches, but different shape–taste matches to Westerners. Cognition, 126(2), 165–172.

Brown, R., Black, A., & Horowitz, A. (1955). Phonetic symbolism in natural languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 54, 312–318.

Carr, P. (2012). English phonetics and phonology: an introduction. Hoboken: Wiley.

Cheung, H., Chen, H.-C., Yip Lai, C., Wong, O. C., & Hills, M. (2001). The development of phonological awareness: effects of spoken language experience and orthography. Cognition, 81(3), 227–241.

Cheung, H., & Chin, H.-C. (2004). Early orthographic experience modifies both phonological awareness and on-line speech processing. Language and Cognitive Processes, 19(1), 1–28.

Cramer, A.O.J, Van Ravenzwaaij, D., Matzke D., Steingroever, H., Wetzels, R., Grasman, R.P., Waldorp, L.J., Wagenmakers, E-J. (2014). Hidden multiplicity in multiway ANOVA: Prevalence, consequences, and remedies. http://www.ejwagenmakers.com/papers.html. Accessed 20 Nov 2014.

Cuskley, C. (2013a). Shared cross-modal associations and the emergence of the lexicon. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Edinburgh. https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/7702. Accessed 15 May 2013.

Cuskley, C. (2013b). Mappings between linguistic sound and motion. Public Journal of Semiotics, 5(1), 37–60.

Cuskley, C., & Kirby, S. (2013). Synaesthesia, cross-modality and language evolution. In J. Simner & E. Hubbard (Eds.), Oxford handbook of synaesthesia (pp. 869–907). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

D’Onofrio, A. (2013). Phonetic detail and dimensionality in word–shape correspondences: refining the bouba–kiki paradigm. Language and Speech,. doi:10.1177/0023830913507694. (preprint).

Davis, R. (1961). The fitness of names to drawings. a cross-cultural study in Tanganyika. British Journal of Psychology, 52(3), 259–268.

Fischer, S. (1922). Uber das enstehen und verstehen von namen. Arch. f. d. Gestalt Psychology, 42, 335–368.

Fort, M., Weiß, A., Martin, A., & Peperkamp, S. (2013). Looking for the bouba–kiki effect in pre-lexical infants. Poster presented at the International Child Phonology Conference (June 12, 2013). Nijmegen: Radboud University.

Fox, C. (1935). An experimental study of naming. American Journal of Psychology, 47, 545–579.

Gallace, A., Boschin, E., & Spence, C. (2011). On the taste of ‘bouba’ and ‘kiki’: an exploration of word–food associations in neurologically normal participants. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(1), 34–46.

Hinton, L., Nichols, J., & Ohala, J. (1994). Sound symbolism. In L. Hinton, J. Nichols, & J. Ohala (Eds.), Sound symbolism (pp. 1–14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hockett, C. (1960). The origin of speech. Scientific American, 203, 88–96.

Imai, M., Kita, S., Nagumo, M., & Okada, H. (2008). Sound symbolism facilitates early verb learning. Cognition, 109, 54–65.

Inglis-Arkell, E. (2010). The bouba–kiki effect. http://www.io9.com/5691770/the-bouba+kiki-effect. Accessed 3 Dec 2013.

Irwin, F., & Newland, E. (1940). A genetic study of the naming of visual figures. Journal of Psychology, 9, 3–16.

Jesperson, O. (1933). Linguistica: Selected papers of O. Jesperson in English, French and German. Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard.

Köhler, W. (1929). Gestalt psychology. New York: Liveright.

Köhler, W. (1930). Gestalt Psychology (British Edition). London: Liveright.

Köhler, W. (1947). Gestalt psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Liveright.

Koriat, A. (1977). The symbolic implications of vowels and of their orthographic representations in two natural languages. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 6(2), 93–104.

Kovic, V., Plunkett, K., & Westerman, G. (2010). The shape of words in the brain. Cognition, 114, 19–28.

Lukatela, K., Carello, C., Shankweiler, D., & Liberman, I. Y. (1995). Phonological awareness in illiterates: observations from Serbo-Croatian. Applied Psycholinguistics, 16, 463–487.

Marks, L. E. (1996). On perceptual metaphors. Metaphor and Symbol, 11(1), 39–66.

Maurer, D., Pathman, T., & Mondloch, C. J. (2006). The shape of boubas: word–shape correspondences in toddlers and adults. Developmental Science, 9(3), 316–322.

Monaghan, P., Mattock, K., & Walker, P. (2012). The role of sound symbolism in word learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 38, 1152–1164.

Newman, S. (1933). Further experiments in phonetic symbolism. American Journal of Psychology, 45, 53–75.

Nielsen, A., & Rendall, D. (2011). The sound of round: evaluating the sound-symbolic role of consonants in the classic takete–maluma phenomenon. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 115–124.

Nielsen, A., & Rendall, D. (2012). The source and magnitude of sound-symbolic biases in processing artificial word material and their implications for language learning and transmission. Language and Cognition, 4(2), 115–125.

Nuckolls, J. B. (1999). The case for sound symbolism. Annual Review of Anthropology, 28, 225–252.

Nygaard, L. C., Cook, A. E., & Namy, L. L. (2009). Sound to meaning correspondences facilitate word learning. Cognition, 112, 181–186.

O’Boyle, M. W., Miller, D. A., & Rahmani, F. (1987). Sound-meaning relationships in speakers of Urdu and English: evidence for a cross-cultural phonetic symbolism. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 16, 273–288.

Ozturk, O., Krehm, M., & Vouloumanos, A. (2013). Sound symbolism in infancy: evidence for word–shape cross-modal correspondences in 4-month-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114, 173–186.

Parise, C., & Spence, C. (2012). Audiovisual crossmodal correspondences and sound symbolism: a study using the implicit association test. Experimental Brain Research, 220, 319–333.

Peña, M., Mehler, J., & Nespor, M. (2011). The role of audiovisual processing in early conceptual development. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1419–1421.

Ramachandran, V., & Hubbard, E. (2001). Synaesthesia: a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(1), 3–34.

Ramachandran, V., & Hubbard, E. (2005). Synaesthesia: a window into the hard problem of consciousness. In L. Robertson & N. Sagiv (Eds.), Synaesthesia: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience (pp. 127–189). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reeve, C. D. C. (1998). Translation of Plato’s Cratylus (HPC Classic Series). Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

Rizzolati, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 169–192.

Robson, D. (2011). Kiki or bouba? In search of language’s missing link. The New Scientist, 2821, 12–16.

Rogers, S., & Ross, A. (1975). A cross-cultural test of the maluma–takete phenomenon. Perception, 5(2), 105–106.

Sapir, E. (1929). A study in phonetic symbolism. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 225.

Saussure, F. (1959). Course in general linguistics. New York: Philosophical Library.

Simner, J. (2011). Yellow-tasting sounds: Synaesthesia’s merging of the senses. Talk presented to Oxford University Department of Psychology, May 2011.

Simner, J., Cuskley, C., & Kirby, S. (2010). What sound does that taste? Perception, 39, 553–569.

Slowiaczek, L. M., Soltano, E. G., Wieting, S. J., & Bishop, K. L. (2003). An investigation of phonology and orthography in spoken-word recognition. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Section A, 56(2), 233–262.

Spector, F., & Maurer, D. (2013). Early sound symbolism for vowel sounds. i-Perception, 4(4), 239.

Stone, G., Vanhoy, M., & Van Orden, G. (1997). Perception is a two way street: feedforward and feedback phonology in visual word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 36, 337–359.

Teller, D. Y. (1979). The forced-choice preferential looking procedure: a psychophysical technique for use with human infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 2, 135–153.

Uznadze, D. (1924). Ein experimenteller bietrag zum problem der psychologischen grundlagen der namengebung. Psychology Forsch, 5, 24–43.

Walker, P., Bremner, J. G., Mason, U., Spring, J., Mattock, K., Slater, A., & Johnson, S. P. (2010). Preverbal infants’ sensitivity to synaesthetic cross-modality correspondences. Psychological Science, 21(1), 21–25.

Ward, J., & Simner, J. (2003). Lexical-gustatory synaesthesia: linguistic and conceptual factors. Cognition, 89, 237–261.

Werner, H. (1957). Comparative psychology of mental development (revised edition). New York: International Universities Press.

Werner, H., & Wapner, S. (1952). Toward a general theory of perception. Psychological Review, 59, 324–338.

Westbury, C. (2005). Implicit sound symbolism in lexical access: evidence from an interference task. Brain and Language, 93, 10–19.

Ziegler, J. C., & Ferrand, L. (1998). Orthography shapes the perception of speech: the consistency effect in auditory word recognition. Psychonomic Bulletin Review, 5(4), 683–689.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cuskley, C., Simner, J. & Kirby, S. Phonological and orthographic influences in the bouba–kiki effect. Psychological Research 81, 119–130 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-015-0709-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-015-0709-2