Abstract

Aims

We aimed at evaluating residual β-cell function in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) while determining for the first time the difference in C-peptide level between patients on basal–bolus compared to those on the basal insulin scheme, considered as an early stage of insulin treatment, together with assessing its correlation with the presence of complications.

Methods

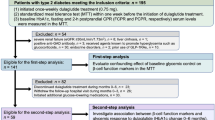

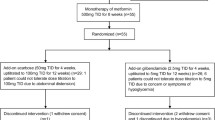

A total of 93 candidates with T2D were enrolled in this cross-sectional study and were categorized into two groups based on the insulin regimen: Basal–Bolus (BB) if on both basal and rapid acting insulin, and Basal (B) if on basal insulin only, without rapid acting injections. HbA1c, fasting C-peptide concentration and other metabolic parameters were recorded, as well as the patient medical history.

Results

The average fasting C-peptide was 1.81 ± 0.15 ng/mL, and its levels showed a significant inverse correlation with the duration of diabetes (r = -0.24, p = 0.03). Despite similar disease duration and metabolic control, BB participants displayed lower fasting C-peptide (p < 0.005) and higher fasting glucose (P = 0.01) compared with B patients. Concentrations below 1.09 ng/mL could predict the adoption of a basal–bolus treatment (Area 0.64, 95%CI:0.521–0.759, p = 0.038, sensitivity 45% and specificity 81%).

Conclusions

Insulin-treated patients with long-standing T2D showed detectable level of fasting C-peptide. Measuring the β-cell function may therefore guide toward effective therapeutic options when oral hypoglycemic agents prove unsuccessful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Health topics. Obesity. https://www.who.int/topics/obesity/en/. https://www.who.int/topics/obesity/en/. 2020

Watanabe M, Risi R, De Giorgi F et al (2020) Obesity treatment within the Italian national healthcare system tertiary care centers: what can we learn? Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00936-1

Hu FB (2011) Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care 34(6):1249–1257. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0442

Basciani S, Camajani E, Contini S et al (2020) Very-low-calorie ketogenic diets with whey, vegetable or animal protein in patients with obesity: a randomized pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105:336. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa336

Basciani S, Costantini D, Contini S et al (2015) Safety and efficacy of a multiphase dietetic protocol with meal replacements including a step with very low calorie diet. Endocrine 48(3):863–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-014-0355-2

Bruci A, Tuccinardi D, Tozzi R et al (2020) Very low-calorie ketogenic diet: a safe and effective tool for weight loss in patients with obesity and mild kidney failure. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020333

Soare A, Khazrai YM, Del Toro R et al (2014) The effect of the macrobiotic Ma-Pi 2 diet versus the recommended diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: the randomized controlled MADIAB trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-11-39

Look ARG, Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G et al (2007) Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 30(6):1374–1383. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-0048

Watanabe M, Gangitano E, Francomano D et al (2018) Mangosteen extract shows a potent insulin sensitizing effect in obese female patients: a prospective randomized controlled pilot study. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10050586

Yilmaz Z, Piracha F, Anderson L, Mazzola N (2017) Supplements for diabetes mellitus: a review of the literature. J Pharm Pract 30(6):631–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190016663070

Soare A, Del Toro R, Khazrai YM et al (2016) A 6-months follow-up study of the randomized controlled Ma–Pi macrobiotic dietary intervention (MADIAB trial) in type 2 diabetes. Nutr Diabetes 6(8):e222. https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2016.29

Watanabe M, Tuccinardi D, Ernesti I et al (2020) Scientific evidence underlying contraindications to the ketogenic diet: an update. Obes Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13053

Tuccinardi D, Farr OM, Upadhyay J et al (2019) Lorcaserin treatment decreases body weight and reduces cardiometabolic risk factors in obese adults: a six-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 21(6):1487–1492. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13655

American Diabetes A (2019) 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42:S90–S102. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S009

Bretzel RG, Eckhard M, Landgraf W, Owens DR, Linn T (2009) Initiating insulin therapy in type 2 diabetic patients failing on oral hypoglycemic agents: basal or prandial insulin? The APOLLO trial and beyond. Diabetes Care 32(Suppl 2):S260-265. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-S319

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report (2020) Centers for disease control and prevention. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA

Swinnen SG, Hoekstra JB, DeVries JH (2009) Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32(Suppl 2):S253-259. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-S318

Landin-Olsson M, Nilsson KO, Lernmark A, Sundkvist G (1990) Islet cell antibodies and fasting C-peptide predict insulin requirement at diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 33(9):561–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00404145

American Diabetes A (2020) 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43:S14–S31. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-S002

Sabbah E, Savola K, Ebeling T et al (2000) Genetic, autoimmune, and clinical characteristics of childhood- and adult-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 23(9):1326–1332. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.9.1326

Di Stasio E, Maggi D, Berardesca E et al (2011) Blue eyes as a risk factor for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 27(6):609–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.1214

Shields BM, Peters JL, Cooper C et al (2015) Can clinical features be used to differentiate type 1 from type 2 diabetes? a systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open 5(11):e009088. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009088

Jones AG, McDonald TJ, Shields BM et al (2016) Markers of beta-cell failure predict poor glycemic response to glp-1 receptor agonist therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 39(2):250–257. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-0258

Lee A, Morley J (1999) Classification of type 2 diabetes by clinical response to metformin-troglitazone combination and C-Peptide criteria. Endocr Pract 5(6):305–313. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP.5.6.305

Jones AG, Besser RE, Shields BM, McDonald TJ, Hope SV, Knight BA, Hattersley AT (2012) Assessment of endogenous insulin secretion in insulin treated diabetes predicts postprandial glucose and treatment response to prandial insulin. BMC Endocr Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-12-6

White MG, Shaw JA, Taylor R (2016) Type 2 diabetes: the pathologic basis of reversible beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes Care 39(11):2080–2088. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0619

Pieralice S, Pozzilli P (2018) Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: a review on clinical implications and management. Diabetes Metab J 42(6):451–464. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.0190

Foley JE, Bunck MC, Moller-Goede DL et al (2011) Beta cell function following 1 year vildagliptin or placebo treatment and after 12 week washout in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes and mild hyperglycaemia: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 54(8):1985–1991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2167-8

Chon S, Gautier JF (2016) An update on the effect of incretin-based therapies on beta-cell function and mass. Diabetes Metab J 40(2):99–114. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2016.40.2.99

Kaneto H, Obata A, Kimura T et al (2017) Beneficial effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and reduction of insulin resistance. J Diabetes 9(3):219–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12494

Leighton E, Sainsbury CA, Jones GC (2017) A Practical review of C-peptide testing in diabetes. Diabetes Ther 8(3):475–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0265-4

Alves MT, Ortiz MMO, Dos Reis G et al (2019) The dual effect of C-peptide on cellular activation and atherosclerosis: protective or not? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 35(1):e3071. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3071

Covic AM, Schelling JR, Constantiner M, Iyengar SK, Sedor JR (2000) Serum C-peptide concentrations poorly phenotype type 2 diabetic end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int 58(4):1742–1750. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00335.x

Haffner SM, Miettinen H, Stern MP (1997) Are risk factors for conversion to NIDDM similar in high and low risk populations? Diabetologia 40(1):62–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001250050643

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants and the nurse Milena Rosati who contributed to patients’ management.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP SM DT RG designed the study. RG, DT, DM, AP, GD, SP, EF conducted research. DT and MW performed analyses. DT, SP, RG, MW, PP and SM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by the University Campus Bio-Medico Ethics Committee # 54/20 OSS ComEt CBM.

Informed consent

All patients signed an informed consent.

Consent for publication

The manuscript received the consent to be published.

Additional information

Managed by Antonio Secchi.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dario, T., Riccardo, G., Silvia, P. et al. The utility of assessing C-peptide in patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Acta Diabetol 58, 411–417 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01634-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01634-1