Abstract

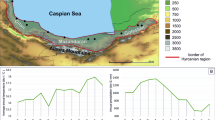

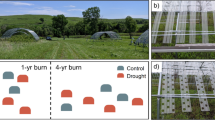

The challenge of understanding how composite disturbances affect ecosystems is a central theme of modern ecology. For instance, anthropogenic footprints and wildfire are increasing globally, but how they combine remains poorly understood. Here, we assessed how a disturbance legacy of about 10-m-wide cutlines, cleared for seismic assessments of fossil fuels, affects wildfire dynamics and species assemblages in boreal peatland forests. One year after the Fort McMurray Horse River wildfire of 2016 (Alberta, Canada), we assessed differences in plant and butterfly assemblages across forests and cutlines, from unburned and severely burned peatlands. We hypothesized that, by reducing fire severity, cutlines could support plants and butterflies in the presence of a severe wildfire (the “refuge hypothesis”). Proportion of burned duff was five times higher in burned forests compared to burned cutlines (53% vs. 11%). We found 107 plant and 46 butterfly taxa, with species richness being, respectively, about 1.4 and 1.7 times higher in lines than in forests, independently from wildfire. Models for single species demonstrated different responses to disturbance, including no responses (25% of species), dominant effects of fire or lines (50%), additive effects (10%), and interactive effects (15%). Cutline refuges occurred for 20% of plant and 70% of butterfly species. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that anthropogenic refuges from fire occur in these peatland forests, yet different patterns of responses confirm the complex effects occurring with composite disturbances. Given that cutlines dissect thousands of square kilometers of boreal forests in North America, further studies should investigate their implications on recovery trajectories of these forests’ succession after wildfire.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arienti MC, Cumming SG, Krawchuk MA, Boutin S. 2009. Road network density correlated with increased lightning fire incidence in the Canadian western boreal forest. International Journal of Wildland Fire 18:970–82.

Bergeron JAC, Pinzon J, Odsen S, Bartels S, Macdonald SE, Spence JR. 2017. Ecosystem memory of wildfires affects resilience of boreal mixedwood biodiversity after retention harvest. Oikos 126:1738–47.

Buma B. 2015. Disturbance interactions: characterization, prediction, and the potential for cascading effects. Ecosphere 6:1–15.

Burke RJ, Fitzsimmons JM, Kerr JT. 2011. A mobility index for Canadian butterfly species based on naturalists’ knowledge. Biodiversity Conservation 20:2273–95.

Burton PJ, Parisien MA, Hicke JA, Hall RJ, Freeburn JT. 2008. Large fires as agents of ecological diversity in the North American boreal forest. International Journal of Wildland Fire 17:754–67.

Certini G. 2005. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 143:1–10.

Côté IM, Darling ES, Brown CJ. 2016. Interactions among ecosystem stressors and their importance in conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283:20152592.

Dabros A, Pyper M, Castilla G. 2018. Seismic lines in the boreal and arctic ecosystems of North America: environmental impacts, challenges, and opportunities. Environmental Reviews 26:214–29.

Dennis RLH, Shreeve TG, Van Dyck H. 2006. Habitats and resources: The need for a resource-based definition to conserve butterflies. Biodiversity Conservation 15:1943–66.

Dornelas M. 2010. Disturbance and change in biodiversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 365:3719–27.

Filicetti AT, Nielsen SE. 2018. Fire and forest recovery on seismic lines in sandy upland jack pine (Pinus banksiana) forests. Forest Ecology and Management 421:32–9.

Fisher JT, Burton AC. 2018. Wildlife winners and losers in an oil sands landscape. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16:323–8.

Flannigan MD, Krawchuk MA, de Groot WJ, Wotton MB, Gowman LM. 2009. Implications of changing climate for global wildland fire. International Journal of Wildland Fire 18:483–507.

George EI, McCulloch RE. 1993. Variable selection via Gibbs sampling. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 88:881–9.

Haddad NM, Brudvig LA, Clobert J, Davies KF, Gonzalez A, Holt RD, Lovejoy TE, Sexton JO, Austin MP, Collins CD, Cook WM, Damschen EI, Ewers RM, Foster BL, Jenkins CN, King AJ, Laurance WF, Levey DJ, Margules CR, Melbourne BA, Nicholls AO, Orrock JL, Song D-X, Townshend JR. 2015. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science Advances 1:e1500052.

Hart SA, Chen HYH. 2008. Fire, logging, and overstory affect understory abundance, diversity, and composition in boreal forest. Ecological Monographs 78:123–40.

Heon J, Arseneault D, Parisien M-A. 2014. Resistance of the boreal forest to high burn rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111:13888–93.

Hintze C, Heydel F, Hoppe C, Cunze S, König A, Tackenberg O. 2013. D3: The Dispersal and Diaspore Database - Baseline data and statistics on seed dispersal. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15:180–92.

Hui FKC. 2016. boral—Bayesian ordination and regression analysis of multivariate abundance data in r. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7:744–50.

Jaeger JAG. 2000. Landscape division, splitting index, and effective mesh size: New measures of landscape fragmentation. Landscape Ecology 15:115–30.

Jarzyna MA, Jetz W. 2016. Detecting the multiple facets of biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 31:527–38.

Keppel G, Van Niel KP, Wardell-Johnson GW, Yates CJ, Byrne M, Mucina L, Schut AGT, Hopper SD, Franklin SE. 2012. Refugia: identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 21:393–404.

Kulakowski D, Veblen TT. 2007. Effect of prior disturbances on the extent and severity of wildfire in Colorado subalpine forests. Ecology 88:759–69.

Lecomte N, Simard M, Bergeron Y. 2006. Effects of fire severity and initial tree composition on stand structural development in the coniferous boreal forest of northwestern Québec, Canada. Écoscience 13:152–63.

New TR. 2014. Insects, fire and conservation. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Paine RT, Tegner MJ, Johnson EA. 1998. Ecological surprises. Ecosystems 1:535–45.

Pollard E. 1977. A method for assessing changes in the abundance of butterflies. Biological Conservation 12:115–34.

R Core Team. 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

van Rensen CK, Nielsen SE, White B, Vinge T, Lieffers VJ. 2015. Natural regeneration of forest vegetation on legacy seismic lines in boreal habitats in Alberta’s oil sands region. Biological Conservation 184:127–35.

Riva F, Acorn JH, Nielsen S. 2018a. Distribution of cranberry blue butterflies (Agriades optilete) and their responses to forest disturbance from in situ oil sands and wildfires. Diversity 10:112.

Riva F, Acorn JH, Nielsen SE. 2018b. Localized disturbances from oil sands developments increase butterfly diversity and abundance in Alberta’s boreal forests. Biological Conservation 217:173–80.

Riva F, Acorn JH, Nielsen SE. 2018c. Narrow anthropogenic corridors direct the movement of a generalist boreal butterfly. Biology Letters 14:20170770.

Roberts D, Ciuti S, Barber QE, Willier C, Nielsen SE. 2018. Accelerated seed dispersal along linear disturbances in the Canadian oil sands region. Scientific Reports 8:4828.

Robinson NM, Leonard SWJ, Ritchie EG, Bassett M, Chia EK, Buckingham S, Gibb H, Bennett AF, Clarke MF. 2013. Refuges for fauna in fire-prone landscapes: Their ecological function and importance. Journal of Applied Ecology 50:1321–9.

Rosa L, Davis KF, Rulli MC, D’Odorico P. 2017. Environmental consequences of oil production from oil sands. Earth’s Future 5:158–70.

Simms CD. 2016. Canada’s Fort McMurray fire: mitigating global risks. Lancet Global Health 4:e520.

Stern E, Riva F, Nielsen S. 2018. Effects of narrow linear disturbances on light and wind patterns in fragmented boreal forests in northeastern Alberta. Forests 9:486.

Swengel AB. 2001. A literature review of insect responses to fire, compared to other conservation managements of open habitat. Biodiversity & Conservation 10:1141–69.

Thom D, Seidl R. 2016. Natural disturbance impacts on ecosystem services and biodiversity in temperate and boreal forests. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 91:760–81.

Turner MG. 2010. Disturbance and landscape dynamics in a changing world. Ecology 91:2833–49.

Weber MGB, Stocks J. 1998. Forest fires and sustainability in the boreal forests of Canada. Ambio 27:545–50.

Acknowledgements

We thank COSIA (CRDPJ 498955), Alberta Innovates—Energy and Environmental Solutions (ABIEES 2070), Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (15GRFFM12), NSERC-CRD, LRIGS via the NSERC-CREATE program (CRD 498955-16, CREATE 397892), Alberta Conservation Association via the ACA Grants in Biodiversity (RES0034641), and Xerces Society via the Joan Mosenthal DeWind Award (RES0036460) for supporting this research. We also thank Fionnuala Carrol and Marcel Schneider for participating in the project as summer undergraduate assistants, Angelo Filicetti, Francis K. C. Hui, Nick M. Haddad, Felix A. H. Sperling, and Hans Van Dyck for insightful comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Turner, Dr. Seidl and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on the manuscript

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riva, F., Pinzon, J., Acorn, J.H. et al. Composite Effects of Cutlines and Wildfire Result in Fire Refuges for Plants and Butterflies in Boreal Treed Peatlands. Ecosystems 23, 485–497 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-019-00417-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-019-00417-2