Abstract

Both Japan and parts of the European Monetary Union have experienced boom and bust in stock and real estate markets, which have been followed by a lasting crisis. The paper analyses the role of a high degree of regional heterogeneity for public debt and monetary policy in the context of crisis. It is shown for Japan that the attempts to maintain regional cohesion via a regional transfer mechanism has contributed to the unprecedented rise in public debt and persistent monetary expansion. Econometric estimations show that in Japan regional redistribution of funds has ensured homogeneous living conditions across Japanese regions pre- and post-crisis. The side condition is monetary expansion. A similar effect could emerge in Europe, if the crisis persists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The boom phases in the southeast Asian countries were accelerated by capital inflows (in form of bank-based lending) from Japan, where the central bank kept interest rates low to facilitate the economic recovery.

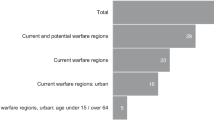

The groupings are shown in Table 2 in the Appendix.

Note that all these numbers refer to GDP per capita after redistribution (see section 3.1)

This created concerns that the EMU might be subjected to a higher likelihood of asymmetric shocks.

Note that the numbers in Figure 3 refer to all now 19 EMU member states during the whole observation period.

We assume for parsimony that inflation rates in Japan and euro area are similar and low.

What is characterized as balance sheet recession (Koo 2003).

The regional distribution of these funds was unknown by 2017.

The local allocation tax is financed by a fraction of national taxes on income, liquor, tobacco and corporate profits (Shirai 2004). It is therefore collected in all Japanese prefectures. Because the tax revenues can be assumed to be larger in the rich prefectures, there is a second redistribution effect on the income side of the redistribution mechanism, which is not captured here because regional data on the income side are not available.

For instance, for the public sector “education” the first of the three factors is a variable measuring the number of pupils and teachers, multiplied by a prefecture-invariant unit cost factor for the respective service branch, and multiplied by a modification factor reflecting prefecture-specific conditions like climate and population density (see Aoki 2008). This shows that the allocation of funds is strongly based on structural factors rather than year-over-year growth rates. This reduces the concern of endogeneity bias in the econometric estimations (see section 4.1.).

“In order to promote its overall harmonious development, the Union shall develop and pursue its actions leading to the strengthening of its economic, social and territorial cohesion.” Art. 174 (1) TFEU

The share of EMU member states is 34 billion euros.

Greece (15,5%), Ireland (6,5%), Italy (47,2%), Spain (20,3%), Portugal (10,4%).

A third CBPP has been set up in Oct. 2014.

Note that ELA credits are reflected in TARGET2 balances.

The provisions for quality of collateral are less strict than for the standard ECB monetary policy operations. The Bank of Greece got the permission by the ECB governing council to lend a maximum of 90 billion euros. When in summer 2015 this limit was rejected to be increased, the Greek authorities had to close banks and introduce capital controls (Götz et al. 2015). When in August 2015 the euro group passed a 86 billion euro resecue package, this included 25 billion euros for the recapitalization of Greek banks (what can be seen as an indication for the insolvency of the Greek banking sector).

In opposite to the „regular“Local Allocation Tax grants, which are supposed to compensate prefectures to assure the deployment of “basic needs” in every Japanese region, National Disbursements are meant to compensate for special events such as natural catastrophes etc. However, National Disbursements are widely a regular redistribution mechanism (see Regional Statistical Database Item Definition; RD1).

Short-term interest rates are a deficient proxy for changes in the monetary policy stance since 1999 because they remain widely unchanged at the zero bound (see Figure 8).

An alternative dummy (rich) is compiled for all prefectures having an income per capita higher than the median prefecture in 1990 (i.e. the year, when the crisis started). The results remain qualitatively unchanged.

References

Abad J, Löffler A, Schnabl G, Zemanek H (2013) Fiscal divergence, current account and TARGET2 Imbalances in the EMU. Intereconomics: Rev Eur Econ Policy, Springer 48(1):51–58

Aoki I (2008) Decentralization and intergovernmental finance in Japan. PRI Discussion Paper Series 8A:4

Arghyrou MG, Kontonikas A (2012) The EMU sovereign-debt crisis: fundamentals, expectations and contagion. J Int Financial Markets, Inst Money 22(4):658–677

Bayoumi T, Collyns C (2000) Post-bubble blues: how Japan responded to asset price Collaps. International Monetary Fund, Washington DC

Belke A, Haskamp U, Schnabl G, Zemanek H (2015) Beyond Balassa and Samuelson: Real convergence, capital flows, and competitiveness in Greece. Forthcoming as CESifo Working Paper

Bernanke B (2002) “Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke at the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman.” University of Chicago, Illinois

Burda MC, Hunt J (2011) What explains the German labor market miracle in the great recession?. NBER Working Paper, 17187. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Economic Studies Program, The Brookings Institution 42(1):273–335. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17187

Caballero RJ, Hoshi T, Kashyab AK (2008) Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. Am Econ Rev 98(5):1943–1977

Cargill TF (2001) Monetary policy, deflation, and economic history, lessons for the Bank of Japan, Monetary and Economic Studies – Special Edition, 2001

Christodoulakis N (2009) Ten years of EMU: convergence, divergence and new policy priorities, Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe, 22

De Grauwe P (2010) Crisis in the eurozone and how to deal with it. CEPS Policy Brief 204. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1604453

Doi T (2010) Poverty Traps with Local Allocation Tax Grants in Japan, Keio/Kyoto Global Coe Discussion Paper Series, DP2010–002

ECB (2015): https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html, as of September 2015

ECB (2016a): https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html as of April 2016

ECB (2016b): https://www.ecb.europa.eu/explainers/tell-me-more/html/anfa_qa.de.html, as of April 2016

European Commission (2015): http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/news-room/content/20150622IPR69218/html/Juncker-Plan-Parlament-billigt-Investitionsplan-zur-Konjunkturbelebung; as of August 22nd 2015

Funabashi Y (1989) Managing the dollar: from the Plaza to the Louvre. Institute for International Economics, Washington DC

Gabrisch H, Staehr K (2014) The euro plus pact: cost competitiveness and external capital flows in the EU countries, ECB Working Paper, 1650

Götz MR, Haselmann R, Krahnen JP, Steffen S (2015) Did emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) oft he ECB delay the bankruptcy of Greek banks? Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe Policy Letter 46

Hashiba H, Kameda K, Sugimura T, Takasaki K (1998) Analysis of landuse change in periphery of Tokyo during last twenty years using the same seasonal landsat data. Adv Space Res 22(5):681–684

Hayashi F, Prescott EC (2002) The 1990s in Japan: a lost decade. Rev Econ Dyn 5:206–235

Hodson D (2013) The eurozone in 2012, whatever it takes to preserve the euro? J Common Mark Stud 51:183–200

Hoshi T, Kashyap A (1999) The Japanese banking crisis: Where did it come from and how will it end?. NBER Working Paper, 7250. https://doi.org/10.3386/w7250

Ishi H (2001) The Japanese tax system. Oxford University Press, New York

Kanaya A, Woo D (2000) The Japanese banking crisis of the 1990s: sources and lessons, IMF Working Paper, 00/7

Koo R (2003) Balance sheet recession: Japan’s struggle with uncharted economics and its global implications. Wiley and Sons, Hoboken

Krishnamurthy A, Nagel S, Vissing-Jorgensen A (2014) ECB policies involving government bond purchases: impacts and channels, Mimeo

Krugman (2010) How much of the world is in a liquidity trap?http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/17/how-much-of-the-world-is-in-a-liquidity-trap/?_r=0 as of June 23rd 2015

Lane P (2015) The European Souvereign debt crisis. J Econ Perspect 26(3):49–68

Mayr J (2008) The financial crisis in Japan – are there similarities to the current situation. CESifo Forum, Ifo Inst Econ Res 9(4):64–68

McKinnon R, Ohno K (1997) Dollar and yen: resolving the economic conflict between the United States and Japan. MIT Press Books, Cambridge

Mochida N (2001) Taxes and transfers in Japan’s local public finances, World Bank Institute, 37171

Powell B (2002) Explaining Japan’s recession. Q J Austrian Econ 5(22):35–50

Schaltegger C, Weder M (2013) Will Europe face a lost decade? A comparison with Japan’s economics crisis, Center for Research in Economics, Management and the Arts Working Paper Series, 2013-03

Schnabl G (2015) Monetary policy and structural decline: lessons from Japan for the European crisis. Asian Econ Pap 14(1):124–150

Schnabl G, Wollmershäuser T (2013) Fiscal divergence and current account imbalances in Europe, CESifo Working Paper Series, 1408

Shibamoto M, Tachibana M (2013) The effect of unconventional monetary policy on the macro economy: evidence from Japan's quantitative easing policy period. Kobe University RIEB Discussion Paper Series 12

Shirai S (2004) The role of local allocation tax and reform agenda in Japan – implication to developing countries. Policy and Governance Working Paper Series, 32

Sinn H-W (2014) Stellungnahme des ifo Instituts und von Prof. Hans-Werner Sinn zur heutigen Erklärung des Bundesverfassungsgerichts zum OMT-Programm der EZB, München 07.02.2014

Sinn H-W, Wollmershäuser T (2012) Target loans, current account balances and capital flows: the ECB’s rescue facility. Int Tax Public Financ 19(4):468–508

Vollmer U, Bebenroth R (2012) The financial crisis in Japan: causes and policy reactions by the Bank of Japan. Eur J Comp Econ 9:155–181

Woo D (2003) In search of “capital crunch”: supply factors behind the credit slowdown in Japan. J Money, Credit, Bank 35:6

Yoshino N, Mizoguchi T (2011) Government debt issues in comparison between Japan and Greece: the fiscal policy rule is urgently needed to establish, Monetary Monthly Report

Acknowledgements

We thank Taiki Murai for the outstanding research assistance and the participants of the 2015 EEFS Conference for useful comments

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, R., Schnabl, G. Regional heterogeneity, the rise of public debt and monetary policy in post-bubble Japan: lessons for the EMU. Int Econ Econ Policy 15, 405–428 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0402-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0402-6