Abstract

In Western Kenya, smallholder dairy production is becoming incrementally commercialized through the commodification and sale of milk through formal market channels. While commercialization is often construed as a way to boost rural livelihoods through increased income from milk, emerging evidence suggests that married women are not directly benefiting from formal milk market participation. This critical issue of gender power imbalance has been framed by development interventions in economic efficiency and social justice perspectives, but thus far interventions in the sector have not addressed how underlying social-market mechanisms embedded in gendered ideology influence smallholder engagement in dairy commercialization. Drawing on feminist theories of power and social embeddedness, this study investigates how gendered power relationships materialize and influence formal milk marketing engagement and practices in Western Kenya. Facilitated discussion groups with smallholder farmers revealed the gendered ideologies and norms that ascribe masculinized meaning to cattle, milk, and commercial enterprise. Key informant interviews with commercial dairy management and farmers were used to identify current practices for increasing women’s formal market participation—namely, direct payments to women for milk deliveries. Findings from this study indicate that cattle and formal dairy market participation are imbued with gendered meaning that create legitimacy around men’s privilege over dairy proceeds. Interventions in the sector aimed at addressing gender power imbalances must acknowledge this dynamic, and accept the social trade-offs and gendered costs of dairy commercialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Gendered ideology around cows varies by dairy system, region, and ethnicity. There is an emergent literature around the power of women as milk managers in pastoral dairy systems in eastern Africa (Parsons and Lombard 2017) and of the changing gender roles and relationships of men and women to dairying in Maasai communities (Allegretti 2018; Bischot 2017) that challenge a universally patriarchal or homogenous “dairy culture”.

We define commodification as “a process whereby assets, goods, and services gradually shift from having a use value purely in terms of subsistence, to having an exchange value as well, meaning that they will be increasingly sold and acquired on the market” (Anderson et al. 2012, p. 384).

The sub-counties of Bomet are: Bomet central, Bomet east, Chepalungu, Konoin, and Sotik. The sub-counties of Nandi are: Nandi Central, Nandi north, Nandi south, Nandi east, and Tinderet. Several key informant interviews occurred at the border of Uasin Gishu and Nandi county in the town of Eldoret. Since Eldoret is more culturally similar to Nandi than other sub-counties of Uasin Gishu, data presented is representative of Nandi and Bomet counties, respectively.

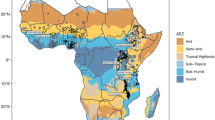

In Kenya, the project focused on the Rift Valley area working in eight districts (Bomet, Buret, Keiyo, Kipkelion, Marakwet, Molo, Nandi, Uasin Gishu, and West Pokot) and two districts in the Central Province (Nyandarua and Nyeri). This study recruited participants from Bomet and Nandi counties, with several interviews occurring in Eldoret, at the border of Nandi and Uasin Gishu counties.

“Check-off” is the practice of using the credit accumulated at a farmer’s hub account to pay for goods and services needed for farming or for household expenses (EADD 2009).

References

Addison, L., and M. Schnurr. 2016. Introduction to symposium on labor, gender and new sources of agrarian change. Agriculture and Human Values 33 (4): 961–965.

Allegretti, A. 2018. Respatializing culture, recasting gender in peri-urban sub-Saharan Africa: Maasai ethnicity and the ‘cash economy’ at the rural-urban interface, Tanzania. Journal of Rural Studies 60: 122–129.

Anderson, D. M., H. Elliott, H. H. Kochore, and E. Lochery. 2010. Camel milk, capital, and gender: The changing dynamics of pastoralist dairy markets in Kenya (pp. 19–34). 2011 Camel Conference School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London, London.

Anderson, D. M., H. Elliot, H. H. Kochore, and E. Lochery. 2012. Camel herders, middlewomen, and urban milk bars: The commodification of camel milk in Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies 6 (3): 383–404.

Baltenweck, I., I. Omondi, E. Waithanji, E. Kinuthia, and M. Odhiambo. 2016. Dairy value chains in East Africa: Why so few women? In A different kettle of fish? Gender integration in livestock and fish research, ed. R. Pyburn, 137–146. Volendam: LM Publishers.

Basu, P., A. Galiè, and I. Baltenweck. 2018. Connecting households and hubs: Gender and dairy value chain development in East Africa. Manuscript in preparation.

Bischot, K. 2017. Patriarchy, colonialism and gender: A long shadow of British colonial institutions amongst the Kenyan Maasai. Bachelor’s thesis, Department of Governance, Economics, and Development. The Hague: Leiden University College, The Hague Universiteit Leiden.

Bögenhold, D. 2013. Social network analysis and the sociology of economics: Filling a blind spot with the idea of social embeddedness. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 72 (2): 293–318.

Cheng’ole, J. M., L. N. Kimenye, and S. G. Mbogoh. 2003. Engendered analysis of the socioeconomic factors affecting smallholder dairy productivity: Experience from Kenya. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 22 (4): 111–123.

Creswell, J. W. 2013. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London: SAGE Publications.

de Bruijn, M. 1997. The hearthhold in pastoral fulbe society, central Mali: Social relations, milk and drought. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 67 (4): 625–651.

Distefano, F. 2013. Understanding and integrating gender issues into livestock projects and programmes: A checklist for practitioners. Rome: FAO.

EADD. 2009. Strategy for integrating gender in EADD. East Africa Dairy Development Project. CGSpaceArchive. https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/1965/Gender%20StrategyEast%20Africa%20Dairy%20Development%20Project.pdf?sequence=2. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

Fafchamps, M. 2016. Formal and informal market institutions: Embeddedness revisited. Working paper, Stanford University, Stanford University2016.

Farnworth, C. R. 2015. Recommendations for a gender dairy NAMA in Kenya prepared for lead and implementing partners to the Kenyan dairy NAMA, Unpublished report 1–35.

Ferguson, J. 1985. The bovine mystique: Power, property and livestock in rural Lesotho. Man 20 (4): 647–674.

Ferrell, A. K. 2012. Doing masculinity: Gendered challenges to replacing burley tobacco in central Kentucky. Agriculture and Human Values 29 (2): 137–149.

Fletschner, D. 2009. Rural women’s access to credit: Market imperfections and intrahousehold dynamics. World Development 37 (3): 618–631.

Galiè, A., A. Mulema, M. Benard, S. Onzere, and K. Colverson. 2015. Exploring gender perceptions of resource ownership and their implications for food security among rural livestock owners in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua. Agriculture & Food Security 4 (1): 1–14.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91 (3): 481–510.

Griffin, P. 2009. Gendering the world bank: Neoliberalism and the gendered foundations of global governance. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Hakansson, N. T. 1994. Grain, cattle, and power: Social processes of intensive cultivation and exchange in precolonial western Kenya. Journal of Anthropological Research 50 (3): 249–276.

Hakizimana, C., P. Goldsmith, A. A. Nunow, A. W. Roba, and J. K. Biashara. 2017. Land and agricultural commercialisation in Meru County, Kenya: Evidence from three models. The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (3): 555–573.

Hebo, M. 2014. Evolving markets, rural livelihoods, and gender relations: The view from a milk-selling cooperative in the kofale district of west arsii, Ethiopia. African Study Monographs 48: 5–29.

Heifer International. 2017. East Africa dairy development: Ending hunger and poverty. Retrieved from https://www.heifer.org/ending-hunger/our-work/programs/eadd/index.html. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

Hill, C. 2003. Livestock and gender: The Tanzanian experience in different livestock production systems. FAO Links Project Case Study 3: 1–4.

Hovorka, A. J. 2012. Women/chickens vs. men/cattle: Insights on gender–species intersectionality. Geoforum 43 (4): 875–884.

Hutchinson, S. 1992. The cattle of money and the cattle of girls among the Nuer, 1930–83. American Ethnologist 19 (2): 294–316.

KIT, Agri-ProFocus, and IIRR. 2012. Challenging chains to change: Gender equity in agricultural value chain development. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, Royal Tropical Institute.

Kohler-Rollefson, I. 2012. Invisible guardians: Women manage livestock diversity. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper No. 174. Rome: FAO.

Lee, J., A. Martin, P. Kristjanson, and E. Wollenberg. 2015. Implications on equity in agricultural carbon market projects: A gendered analysis of access, decision making, and outcomes. Environment and Planning A 47 (10): 2080–2096.

Lenjiso, B. M., J. Smits, and R. Ruben. 2016. Transforming gender relations through the market: Smallholder milk market participation and women`s intra-household bargaining power in Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies 52 (7): 1002–1018.

Lie, J. 1997. Sociology of markets. Annual Review of Sociology 23: 341–360.

Makoni, N. 2013. White gold: Opportunities for dairy sector development in East Africa. Wageningen: Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR (University & Research centre). CDI report CDI-14-006.

McKune, S. L., E. C. Borresen, A. G. Young, T. D. Auria Ryley, S. L. Russo, A. Diao Camara, M. Coleman, and E. P. Ryan. 2015. Climate change through a gendered lens: Examining livestock holder food security. Global Food Security 6: 1–8.

Muteshi, J. K. 1998. A refusal to argue with inconvenient evidence: Women, proprietorship and Kenyan Law. Dialectical Anthropology 23 (1): 55–81.

Mutinda, G. 2011. Stepping out in the right direction: Integrating gender in EADD. A presentation prepared for the Gender and Market Oriented Agriculture (AgriGender 2011) Workshop, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 31st January-2nd February 2011. Nairobi: East Africa Dairy Development Project (EADD).

Nakazibwe, P., and W. Pelupessy. 2014. Towards a gendered agro-commodity approach. Journal of World-Systems Research 20 (2): 229–256.

Niamir-Fuller, M. 1994. Women livestock managers in the third world: Focus on technical issues related to gender roles in livestock production. Rome: IFAD.

Njuki, J., S. Kaaria, A. Chamunorwa, and W. Chiuri. 2011. Linking smallholder farmers to markets, gender and intra-household dynamics: Does the choice of commodity matter? The European Journal of Development Research 23 (3): 426–443.

Oboler, R. S. 1996. Whose cows are they, anyway? Ideology and behavior in Nandi cattle “ownership” and control. Human Ecology 24 (2): 255–272.

Omondi, I., K. Zander, S. Bauer, and I. Baltenwelk. 2014. Using dairy hubs to improve farmers’ access to milk markets gender and its implications. ILRI Internal Report 2014: 1–22.

Parsons, I., and M. Lombard. 2017. The power of women in dairying communities of eastern and southern Africa. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 52 (1): 33–48.

Pircher, T., C. J. M. Almekinders, and B. C. G. Kamanga. 2013. Participatory trials and farmers’ social realities: Understanding the adoption of legume technologies in a Malawian farmer community. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 11 (3): 252–263.

Quisumbing, A. R., and L. Pandolfelli. 2009. Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers: Resources, constraints, and interventions. Paper presented at the IFPRI Discussion Paper 00882, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division.

Quisumbing, A. R., D. Rubin, C. Manfre, E. Waithanji, M. van den Bold, D. Olney, N. Johnson, and R. Meinzen-Dick. 2015. Gender, assets, and market-oriented agriculture: Learning from high-value crop and livestock projects in Africa and Asia. Agriculture and Human Values 32: 705–725.

Rice, K. 2017. Rights and responsibilities in rural South Africa: Implications for gender, generation, and personhood. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23 (1): 28–41.

Sanginga, P., J. Njuki, and E. Waithanji. 2013. Improving the design and delivery of gender outcomes in livestock research for development in Africa. In Women, livestock ownership, and markets: Bridging the gender gap in eastern and southern Africa, eds. J. Njuki, and P. C. Sanginga, 129–142. London: Routledge.

Simiyu, R. R., and D. Foeken. 2013. ‘I’m only allowed to sell milk and eggs’: Gender aspects of urban livestock keeping in Eldoret, Kenya. The Journal of Modern African Studies 51 (4): 577–603.

Tavenner, K. 2016. A feminist political ecology of indigenous vegetables in a South African protected area community. PhD dissertation, Department of Rural Sociology and Women’s Studies. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University.

Tavenner, K., and T. A. Crane. 2016. Guide to best practices for socially and gender-inclusive development in Kenyan intensive dairy sector. ILRI project report. Nairobi: ILRI.

Tavenner, K., S. Fraval, I. Omondi, and T. A. Crane. 2018. Gendered reporting of household dynamics in the Kenyan dairy sector: Trends and implications for low emissions development. Gender, Technology and Development 22 (1): 1–19.

Valdivia, C. 2001. Gender, livestock assets, resource management, and food security: Lessons from the SR-CRSP. Agriculture and Human Values 18 (1): 27–39.

Weiler, V., H. M. J. Udo, T. Viets, T. A. Crane, and I. J. M. De Boer. 2014. Handling multi-functionality of livestock in a life cycle assessment: The case of smallholder dairying in Kenya. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 8: 29–38.

Acknowledgements

This work was implemented as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from CGIAR Fund Donors and through bilateral funding agreements. For details, please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tavenner, K., Crane, T.A. Gender power in Kenyan dairy: cows, commodities, and commercialization. Agric Hum Values 35, 701–715 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-9867-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-9867-3