Abstract

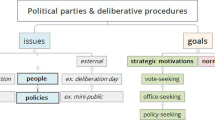

In this paper, I review and compare major literature on goals in argumentation scholarship, aiming to answer the question of how to take the different goals of arguers into account when analysing and evaluating public political arguments. On the basis of the review, I suggest to differentiate between the different goals along two important distinctions: first, distinguish between goals which are intrinsic to argumentation and goals which are extrinsic to it and second distinguish between goals of the act of arguing and goals of argumentative interactions. Furthermore, I propose to analyse public political arguments as multi-purposive activity types and reconstruct the argumentative exchanges as a series of simultaneous discussions. This enables us to examine public political arguments from a perspective in which the intrinsic goals of argumentation are in principle instrumental for the achievement of the socio-political purposes of argumentation, and consequently, it makes our assessment of the argumentative quality of the argument also indicative of the quality of the socio-political processes to which the arguments contribute.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The assumption that communicative behaviour is driven by multiple goals and that the discursive choices can be explained by appeal to these goals underlie much of the research in communication. In probably one of the most influential works, Clark and Delia, driven by their interest in the study of communicative strategies, identified three main types of goals: instrumental, interpersonal and identity (1979, pp. 199–200). They suggested that participants in every communicative situation have goals that belong to three domains: a communicator can have goals that are related to the specific obstacle or problem defining the task of the communicative situation, i.e. instrumental or task goals, as well as goals involving the establishment of maintenance of a relationship with the other, i.e. interpersonal goals, and goals related to the self-image conveyed to the other, i.e. identity goals. Dependent on the situation, the different types of goals can have variant weights and the communicator’s discursive choices are best understood as an attempt to pursue them (ibid).

Bermejo-Luque makes a very strong claim against defining argumentation in terms of a function. Like van Eemeren and Grootendorst and Johnson, she considers justification to be constitutive of argumentation, but she would rather speak of values and goals than of functions. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this paper, the focus is on goals in general, which may render this distinction less crucial.

The essential condition for van Eemeren and Grootendorst’s illocutionary act complex argumentation states that “advancing the constellation of statements S1, S2 (,…, Sn) counts as an attempt by S to justify O to L’s satisfaction, i.e. to convince L of the acceptability of O” (1984, p. 43, my emphasis). They explain that arguing and convincing are two conventionally linked but distinct speech acts. The two speech acts have different happiness conditions: while the (illocutionary) speech act of arguing is correct and happy if the listener understands that the speaker advanced pro-argumentation, i.e. is justifying an opinion, for the (perlocutionary) speech act of convincing to be happy, the listener needs to accept the claim that is being justified, i.e. being convinced (1984, pp. 49–50).

The view that persuasion is a defining feature of argumentation is challenged by Marianne Doury (2011). Doury sees persuasion as a goal of argumentation in only some but not all contexts. Her challenge is based on the analysis of argumentative exchanges of people who do not disagree about the claim at issue but still argue. The view advocated by Doury is very interesting as it does not take disagreement about standpoints to be a precondition for argumentation.

In this paper, I am assuming that the resolution of differences of opinion, being the goal of a critical discussion, needs to be understood as a critical resolution, i.e. a resolution that is reached by means of critical testing, rather than a consensual resolution as it is often taken by critics of the pragma-dialectical approach. As van Eemeren and Houtlosser clearly put it, “in this model (of a critical discussion) argumentative discourse is conceived as aimed at resolving a difference of opinion by putting the acceptability of the ‘standpoints’ at issue to the test” (2003, p. 387, my emphasis).

Walton and Krabbe identify six main dialogue types (1995, pp. 65–67). In addition to negotiation and deliberation, there is persuasion, inquiry, information-seeking and eristic dialogues. Walton and Krabbe identify these dialogue types are the major contexts in which argumentation occurs, but emphasise that real-life argumentation also occurs in contexts in which two or more of the main dialogue types are mixed. Political debate is an example of mixed dialogue types: It is partly information-seeking, partly deliberation, partly eristic, partly negotiation, and partly persuasion (ibid).

It is fair to consider the goals that characterise Walton and Krabbe's dialogue types as extrinsic goals. Otherwise, what would make these different dialogue types all argumentative, if not sharing the same intrinsic goal, that of argumentation? However, these goals are not all on a par: While for most dialogue types (e.g., negotiation, deliberation ... etc) the goal is context-dependent and therefore extrinsic, the goal of the persuasion dialogue is rather intrinsic. Walton and Krabbe’s dialogue types combine normative and descriptive characteristics. See Lewinski (2010, Ch. 2) for a good critique on this issue.

For example, the use of argumentation for inquiry is dependent on argument as persuasion: “we first learn the practice of persuading others then we can use that practice to inquire; that is, to persuade ourselves” (Johnson 2000: p. 149).

The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic goals is important when considering whether argumentation has any “determinable” function that can warrant norms for argument evaluation (See e.g. Goodwin 2007). Goodwin’s claim that argumentation has no “determinable” function would not be considered so provocative if by function we would understand extrinsic function. After all, argumentation scholars do not seem to disagree about the fact that argumentation has many (extrinsic) functions: argumentation has many uses and can fulfil a multitude of purposes. But what if Goodwin means to say that argumentation has no determinable intrinsic function? Indeed, while most of the functions Goodwin challenges are extrinsic, Goodwin seems to be also challenging functions that are considered intrinsic such as convincing (2007: p. 80). Being clear on which of the two types of functions is at stake would have made Goodwin’s position clearer and allowed a better discussion of it. For an elaborate critical response to Goodwin, see Patterson (2011).

Goals that motivate arguers are also important for Goodwin (2007). In challenging the different functions that are attributed to argumentation, she uses examples where arguers are not motivated by the goals underlying these functions (ibid).

See examples of dialectical and rhetorical goals in van Eemeren (2010), p. 45.

The difference between motivating and normative goals is sometimes also important, but this is a difference that cuts across the categories already distinguished: the goals that motivate arguers can be either intrinsic or extrinsic to argumentation, and they can be either individual or shared between arguers.

Considering the political purposes of public political arguments as “institutional” is in line with Zarefsky’s understanding of political argumentation as institutionalised in the sense of having recurrent patterns and characteristics that allow generalisations (2008).

These are not the only typical initial disagreements that give rise to issues to be discussed in EP debates (for more issue see Mohammed 2013a). However, for the sake of illustration, I restrict myself to these two, which seem to be typical of Parliamentary argumentative practices. In Prime Minister’s Question Time in the British House of Commons, for example, the two initial disagreements are also typical of the argumentative practice (Mohammed, 2009). This is hardly not surprising, given the inter-dependence between accountability and policy-making.

For examples of how arguers strategically craft their contributions to address several issues simultaneously, see Mohammed (2013b, forthcoming).

The TFTP was set up by the U.S. Treasury Department shortly after the attacks of 11 September 2001, and was approved by the EP under the Lisbon Treaty. Supporters of TFTP argue that the agreement has generated significant intelligence data that helped the U.S. and EU States in ‘their fight against terrorism’. But problems in the implementation of the agreement have driven many to call it into question. The media reports based on the claims made by Snowden made these sceptical voices even more prominent.

The general mood in the debate was in favour of the suspension, even though the EPP, the largest party in the EP since 1999, was against it. A week after the debate, different political groups proposed motions for action. The vote on the motions took place in the plenary session of 23 October and a joint motion for a resolution was approved, in which the EP called on the Commission to “suspend the Terrorist Finance Tracking Program (TFTP) agreement with the US in response to the US National Security Agency's alleged tapping of EU citizens' bank data held by the Belgian company SWIFT”. The resolution was passed by 280 votes to 254, with 30 abstentions. Although the EP has no formal powers to initiate the suspension or termination of an international deal, "the Commission will have to act if Parliament withdraws its support for a particular agreement", says the approved text.

These are by no means the only initial disagreements that are discussed in the TFTP debate. There are certainly other interesting disagreements. The choice of which disagreement(s) to consider is eventually based on the socio-political processes the analysit is interested in.

The EPP, S&D, ALDE, and Greens/EFA were the four biggest political groups in the EP at the time of the debate. More information on Political groups can be found at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/en/007f2537e0/Political-groups.html.

References

BBC News. 2013. The week ahead at the European Parliament. Retrieved 26 Oct 2013 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-24419555.

Bermejo-Luque, L. 2011. Giving reasons: A linguistic–pragmatic approach to argumentation theory. Dordrecht: Springer.

Clark, R.A., and J.G. Delia. 1979. Topoi and rhetorical competence. The Quarterly Journal of Speech 65: 187–206.

Corbett, R., F. Jacobs, and M. Shackleton. 2011. The European parliament. London: John Harper Publishing.

Craig, R.T. 1990. Multiple goals in discourse: An epilogue. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 9(1): 163–170.

Dillard, J.P. 1990. The nature and substance of goals in tactical communications. In The psychology of tactical communication, ed. M.J. Cody, and M.L. McLaughlin. Avon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Doury, M. 2011. Preaching to the converted. Why argue when everyone agrees? Argumentation 26(1): 99–114.

European Parliament. 2013. Suspension of the SWIFT agreement as a result of NSA surveillance (debate). Retrieved 2 Dec 2013 from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=CRE&reference=20131009&secondRef=ITEM-019&language=EN.

Fairclough, I., and N. Fairclough. 2012. Political discourse analysis: A method for advanced students. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, M.A. 1997. Coalescent argumentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gilbert, M.A. 2007. Natural normativity: Argumentation theory as an engaged discipline. Informal Logic 27(2): 149–161.

Goodwin, J. 2007. Argument has no function. Informal Logic 27(1): 69–90.

Habermas, J. 1984. The theory of communicative action vol 1: Reason and the rationalization of society. Boston: Beacon Press.

Hamblin, C.L. 1970. Fallacies. London: Methuen.

Jacobs, S., S. Jackson, and S. Stearns. 1991. Digressions in argumentative discourse: Multiple goals, standing concerns, and implicatures. In Understanding face-to-face interaction: Issues linking goals and discourse, ed. K. Tracy, 43–61. New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Johnson, R.H. 2000. Manifest rationality. A pragmatic theory of argument. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lewiński, M. 2010. Internet political discussion forums as an argumentative activity type: A pragma-dialectical analysis of online forms of strategic manoeuvring with critical reactions. Amsterdam: SicSat.

Mohammed, D. 2009. The honourable gentleman should make up his mind. Strategic manoeuvring with accusations of inconsistency in Prime Minister’s question time. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

Mohammed, D. 2011. Strategic manoeuvring in simultaneous discussions. In Argumentation: Cognition and Community, ed. F. Zenker. Proceedings of the 9th international conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), May 18–21, 2011. Windsor, ON (CD ROM), pp. 1–11.

Mohammed, D. 2013a. Pursuing multiple goals in European Parliamentary debates: EU immigration policies as a case in point. Journal of Argumentation in Context 2(1): 47–74.

Mohammed, D. 2013b. Hit two birds with one stone: Strategic manoeuvring in the after-Mubarak era. In ed. A.L. Sellami, Argumentation, rhetoric, debate and pedagogy: Proceedings of the 2013 4th International conference on argumentation, rhetoric, debate, and pedagogy (pp. 95–116). Doha.

Mohammed, D. forthcoming. It is true that security and Schengen go hand in hand. Strategic manoeuvring in the multi-layered activity type of European Parliamentary debates. In Dialogues in Argumentation, ed. R. von Burg. Windsor Studies in Argumentation.

Patterson, S. 2011. Functionalism, normativity and the concept of argumentation. Informal Logic 31(1): 1–25.

Toulmin, S.E. 1958. The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tracy, K. 1984. The effect of multiple goals on conversational relevance and topic shift. Communication Monographs 51: 274–287.

Tracy, K., and N. Coupland. 1990. Multiple goals in discourse: An overview of issues. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 9(1): 1–13.

Tracy, K. 1991. ed. Understanding face-to-face interaction: Issues linking goals and discourse. New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Walton, D., and E.C.W. Krabbe. 1995. Commitment in dialogue: Basic concepts of interpersonal reasoning. Albany: SUNY Press.

van Eemeren, F.H. 2010. Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse, extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

van Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 1984. Speech acts in argumentative discussions: A theoretical model for the analysis of discussions directed towards solving conflicts of opinion. Dordrecht: Foris.

van Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 1995. The Pragma-Dialectical Approach to Fallacies. In Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, eds. H.V. Hansen and R.C. Pinto, 130–144. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

van Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 2004. A systematic theory of argumentation. The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Eemeren, F.H., and P. Houtlosser. 2003. The development of the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentation. Argumentation 17(4): 387–403.

van Eemeren, F.H., and P. Houtlosser. 2005. Theoretical construction and argumentative reality: An analytic model of critical discussion and conventionalised types of argumentative activity. In The uses of argument: Proceedings of a conference at McMaster University, ed. D. Hitchcock, 75–84. Windsor: Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation.

van Eemeren, F.H., and P. Houtlosser. 2006. Strategic maneuvering: A synthetic recapitulation. Argumentation 20(4): 381–392.

Wenzel, J.W. 1979. Jiirgen Habermas and the dialectical perspective on argumentation. Journal of the American Forensic Association 16: 83–94.

Zarefsky, D. 2008. Strategic maneuvering in political argumentation. Argumentation 22: 317–330.

Acknowledgments

(I am grateful to Marianne Doury for her comments on an earlier version of this manuscript and to the two anonymous Journal Argumentation reviewers for their critical feedback. I acknowledge the financial support of the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through grant no. SFRH/BPD/76149/2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 The Introductory Statement of Commissioner Malmström

Madam President, ladies and gentlemen, I am here tonight to inform you about the actions I have decided to take following the press allegations about the possible access of the US National Security Agency (NSA) to the data exchange through the EU-US Terrorist Finance Tracking Programme (TFTP) Agreement.

On 24 September I met many of you in the LIBE Committee and informed you about the ongoing efforts to follow up on this matter, which is of course of great concern. The discussions in LIBE were helpful and confirmed the need to clarify a number of issues.

Since the first allegations appeared in the press, as I told you then, I have immediately taken action. In July, I sent a first letter to my US counterpart, and on 11 September I called on the Under-Secretary for the Treasury Department, Mr Cohen, and told him that I was waiting for substantial information on the alleged tapping. The next day I also sent him a letter, in which I requested the opening of consultations under Article 19 of the TFTP Agreement. As you know, this is the procedure that is regulated in the agreement in case there are questions or things that need to be clarified.

In reply to my letter—and I shared the letter with the LIBE committee on 23 September—the US Authority provided some explanations. But several important questions remained unanswered. I therefore, this Monday, met with Under-Secretary Cohen in Brussels and I appreciate that he came despite the budgetary constraints. We had open and very long discussions and he clarified a number of points.

During that meeting, Under-Secretary Cohen explicitly confirmed that since the entry into force of the TFTP Agreement the US Government has not collected financial messaging from SWIFT in the EU. He also said that the US Government has not served any subpoenas on SWIFT in the EU during that period. I insisted to have that very important confirmation statement confirmed in writing.

We also discussed in some detail the established channels through which the US does obtain financial information in SWIFT format used by financial institutions worldwide. Also on this, I asked for further explanations in writing, in order to be absolutely sure that these mechanisms do not conflict with the TFTP Agreement.

At this stage, therefore, our contacts with SWIFT and the US Government have not really given any evidence that the TFTP Agreement had been violated. Some further clarifications are, however, needed before we can draw full conclusions. Concluding the consultations with the US remains on the top of my agenda and also for my staff and we intend to do our best to get all information needed in the very near future.

Of course, I will make sure that you are fully informed about future developments at the outcome of these consultations.

1.2 Statement of Brigit Sippel, Speaking on Behalf of the S & D Group

(translated from the original German, in line with the immediate interpretation provided at the time of the debate)

Madam President! Mrs Malmström, but I want to remind you once again that before the recent revelations there were already problems with the implementation of this Agreement. And secondly, I should remind you once again that long before the current agreement was in force, the USA was using SWIFT data on servers, and this fact is then made manifest only through media reports.

The current media reports of very serious allegations, however, put the agreement in my view, actually into question. You yourself mentioned the letter to David Cohen, and the wording of the answer is indeed very remarkable, namely: the Terrorist Finance Tracking Programme is a good thing to get to SWIFT data that you just will not get any other way. What other means is he talking about? And also the additional indication that since the agreement is no data has been taken from SWIFT in Europe—yes, but they can actually get it from third countries perhaps by SWIFT, or who knows!

That would mean to me that this Agreement cannot be continued.

Our colleague Díaz de Mera said we must not act hastily here. The criticism of the Agreement and the reports in the media are not only since yesterday on the table/they simply cannot be brushed under the carpet! I want to come back to what the Commission had promised us a long time ago, namely there would be a proposal on the extraction of data on EU territory! But there is still no proposal, and that is a cause for criticism. So now we act hastily if we suspend the Agreement? No!

If we had evidence, then we would not be suspending the Agreement, but we’ll be cancelling it. Now we need to suspend the agreement now in order to have the opportunity to intensively investigate and also exercise pressure on the USA to bring evidence on whether or not a violation has occurred. In the meantime, we must not allow our names to be given to an agreement that allows for EU citizen data to be abused!

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammed, D. Goals in Argumentation: A Proposal for the Analysis and Evaluation of Public Political Arguments. Argumentation 30, 221–245 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-015-9370-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-015-9370-6