Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate a unique approach to cancer risk assessment for improved access by smaller rural communities.

Methods

Local, on-site nurse navigators were trained and utilized as genetic counselor extenders (GCEs) to provide basic risk assessment and offer BRCA1/2 genetic testing to select patients based on a triaging process in collaboration with board-certified genetic counselors (CGCs).

Results

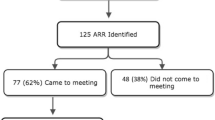

From August 2012 to July 2014, 12,477 family history questionnaires representing 8937 unique patients presenting for a screening mammogram or new oncology appointment were triaged. Of these, 8.2 % patients were identified at increased risk for hereditary breast cancer, and 4.2 % were identified at increased risk for other hereditary causes of cancer. A total of 75 of 1130 at-risk patients identified (6.6 %) completed a genetic risk assessment appointment; 23 with a GCE and 52 with a CGC. A review of the completed genetic test requisition forms from a 9-year pre-collaboration time period found that 16 % (20/125) did not appear to meet genetic testing criteria. Overall, there was a fourfold increase in patients accessing genetic services in this study period compared to the pre-collaboration time period. Efficiency of this model was assessed by determining time spent by the CGC in all activities related to the collaboration, which amounted to approximately 16 h/month. Adjustments have been made and the program continues to be monitored for opportunities to improve efficiency.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of CGCs and GCEs collaborating to improve access to quality services in an efficient manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Evans DGR et al (2014) The Angelina Jolie effect: how high celebrity profile can have a major impact on provision of cancer related services. Breast Cancer Res 16(5):442

Borzekowski DLG et al (2014) The Angelina effect: immediate reach, grasp, and impact of going public. Genet Med 16(7):516–521

Dunlop K, Kirk J, Tucker K (2014) In the wake of Angelina managing a family history of breast cancer. Aust Fam Physician 43:76–78

Raphael J et al (2014) The impact of Angelina Jolie’s (AJ) story on genetic referral and testing at an academic cancer centre. ASCO Meeting Abstracts 32(26_suppl):44

van der Post RS et al (2015) Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical guidelines with an emphasis on germline CDH1 mutation carriers. J Med Genet 52(6):361–374

Vasen HFA et al (2013) Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut 62:812–823

Thakker RV et al (2012) clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). J Clin Endocr Metab 97(9):2990–3011

Syngal S et al (2015) ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 110(2):223–262

Nelson HD et al (2014) Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: a systematic review to update the U.S. preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 160(4):255–266

Daly M et al (2015) NCCN guidelines version 2.2015: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian. NCCN guidelines 2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2015

Moyer VA (2014) risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 160(4):271–281

Rosenberg SM et al (2016) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation testing in young women with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 6:730–736

Kurtzman, S et al NAPBC Standards Manual, A.C.O. Surgeons, Editor. 2014

Greene FL et al (2014) Cancer program standards 2012: ensuring patient-centered care v1.2.1. American College of Surgeons, Chicago

Langreth R (2013) Cigna demands counseling for breast test in myriad threat, in Bloomberg Buisiness

Cragun D et al (2014) Differences in BRCA counseling and testing practices based on ordering provider type. Genet Med 17:51–57

Riley JD et al (2015) Improving molecular genetic test utilization through order restriction, test review, and guidance. J Mol Diagn 17(3):225–229

Douma KFL, Smets EMA, Allain DC (2016) Non-genetic health professionals’ attitude towards, knowledge of and skills in discussing and ordering genetic testing for hereditary cancer. Fam Cancer 15(2):341–350

Vadaparampil ST et al (2015) Pre-test genetic counseling services for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer delivered by non-genetics professionals in the state of Florida. Clin Genet 87:473–477

Brierley KL et al (2010) Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med 74(7):413–423

Brierley KL et al (2012) adverse events in cancer genetic testing: medical, ethical, legal, and financial implications. Cancer J 18(4):303–309. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182609490

Bonadies DC et al (2014) adverse events in cancer genetic testing: the third case series. Cancer J 20(4):246–253. doi:10.1097/PPO.0000000000000057

NSGC 2016 Professional status survey: executive summary (2016). www.nsgc.org. Accessed 8 Oct 2016

NSGC. 2014 NSGC Professional Status Survey Executive Summary (2014) The NSGC Professional Status Survey (PSS) offers an inside view of the profession, including salary ranges, benefits, work environments, faculty status and even job satisfaction. www.nsgc.org. Accessed 28 Apr 2014

Sifri R et al (2003) Use of cancer susceptibility testing among primary care physicians. Clin Genet 64(4):355–360

Wideroff L et al (2003) Physician use of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: results of a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 12(4):295–303

Hooker GW et al (2014) Presented abstracts from the Thirty Third Annual Education Conference of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (New Orleans, LA, September 2014): large scale changes in cancer genetic testing with variable integration of expanded gene panels. J Genet Couns 23(6):1070–1071

Bookman T (2016) Genetic counselors struggle to keep up with hugh new demand. Kaiser Health News

Pan V et al (2016) Expanding the genetic counseling workforce: program directors/’ views on increasing the size of genetic counseling graduate programs. Genet Med 18:842–849

Schwartz MD et al (2014) Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:618–626

McDonald E et al (2014) Acceptability of telemedicine and other cancer genetic counseling models of service delivery in geographically remote settings. J Genet Couns 23(2):221–228

Cohen SA et al (2013) Identification of genetic counseling service delivery models in practice: a report from the NSGC service delivery model task force. J Genet Couns 22(4):411–421

MacDonald DJ, Blazer KR, Weitzel JN (2010) Extending comprehensive cancer center expertise in clinical cancer genetics and genomics to diverse communities: the power of partnership. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8(5):615–624

Chang Y et al (2016) ReCAP: economic evaluation alongside a clinical trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for BRCA1/2 mutations in geographically underserved areas. J Oncol Pract 12(1):59

Narod S (2015) Genetic testing for BRCA mutations today and tomorrow—about the about study. JAMA Oncol 1:1225–1226

Cohen S, McIlvried D (2013) Improving access with a collaborative approach to cancer genetic counseling services: a pilot study. Community Oncol 10(8):227–234

Moyer VA (2013) Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 159:698–708

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins (2009) Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Gynecol Oncol 113(1):6–11

American Society Of Clinical Oncology (2003) American society of clinical oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 21(12):2397–2406

Mazzola E et al (2014) Recent BRCAPRO upgrades significantly improve calibration. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 23(8):1689–1695

Berry DA et al (2002) BRCAPRO validation, sensitivity of genetic testing of BRCA1/BRCA2, and prevalence of other breast cancer susceptibility genes. J Clin Oncol 20(11):2701–2712

Bellcross CA et al (2009) Evaluation of a breast/ovarian cancer genetics referral screening tool in a mammography population. Genet Med 11(11):783–789

Bellcross C (2010) Further development and evaluation of a breast/ovarian cancer genetics referral screening tool. Genet Med 12(4):240

Jones JL et al (2005) Evaluation of hereditary risk in a mammography population. Clin Breast Cancer 6(1):38–44

McDonnell C et al (2013) Self administered screening for hereditary cancers in conjunction with mammography and ultrasound. Fam Cancer 12:651–656

Ozanne EM et al (2009) identification and management of women at high risk for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome. Breast J 15(2):155–162

Miller CE et al (2014) Genetic counselor review of genetic test orders in a reference laboratory reduces unnecessary testing. Am J Med Genet Part A 164(5):1094–1101

Moyer VA (2014) Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 160(4):271–281

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kathryn Murray, MS, CGC for allowing them to use the term “Genetic Counselor Extender,” which she coined. The authors would also like to acknowledge their current GCEs, Michelle Meyer, RN and Lisa Ruehr, RN, who have made this project possible as well as Heather Elston, BS, who assisted with data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

All procedures followed here were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Written informed consent was not required by St. Vincent Institutional Review Board (2014-053), because no identifying information was collected.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, S.A., Nixon, D.M. A collaborative approach to cancer risk assessment services using genetic counselor extenders in a multi-system community hospital. Breast Cancer Res Treat 159, 527–534 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3964-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3964-z