Abstract

Uttar Pradesh is one of the significant political spaces that offers a genuine academic analysis to Electoral Geography students. This political space interestingly presents the electoral dynamics rooted in many socio-cultural variants and has a more significant bearing on the electoral behavior of the masses in Uttar Pradesh. In this respect, the present paper organizes its conceptual design to correlate the electoral behavior of voters of Uttar Pradesh with the effects of the elements of culture and social structure. Primarily, this paper analyses the factors that control electoral behavior. It includes demographic politics, religion, cultural symbols, language, social stratification (Caste and sub-caste), rural–urban divide, and identity politics. These are the dominant factors in the social space of Uttar Pradesh that essentially controls the electoral behavior. The tendencies involved in the recent elections are observed in terms of electoral mobilization by political parties in Uttar Pradesh. The spatiality of populism, media campaign, caste alliance, religious sentiments, nationalistic issues, and leadership traits is the emerging trends utilized in the multiparty political democracy in Uttar Pradesh. Hence, the article is an ethnographic exploration of the relations between politics and social stratification, religion, and caste/community in Uttar Pradesh. This paper aims to examine the implications of cultural mobilization on these lines. Further, it observes how power has been transferred from parties that claim to favor social justice and subaltern politics like Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party to Bhartiya Janta Party. This paper is generally based on secondary and archival sources; census data and electoral data are extracted from Newspaper reports, census, and the Election Commission of India. Primarily, It is a qualitative study where descriptive and analytical methods are applied. Arguments are framed through case studies and electoral data reports. The quantitative aspect of the analysis is represented through diagrams, graphs, and election statistics. The study shows that the evolution of the politics of Uttar Pradesh shows a visible sign of polarization mainly on the communal lines. Issues relating to the development of the region and its people are often sidelined in the face of communal division. Other factors like the ideology of the political party, local issues, caste, gender, and personality of the candidate intervene but with marginal effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Election, one of the important features of indirect democracy, is organized to choose representatives from political spaces' fragmented or diversified constituencies. It is the process through which a group of individuals elects a number of representatives from respective constituencies. However, during the election, various factors are linked to the electoral dynamic that changes, controls and determines the electoral preferences, electoral campaign, issues, and agenda of elections (Swaminathan & Palshikar, 2020). In the election system, even these socio-cultural and economic factors also influence the political mobilization, selection of the candidate, choice of candidate, etc. The performances of political parties from the respective constituencies are also affected by particular factors. The controlling elements are generally rooted in the identity of place as genre de loci and sometimes come as an external overpowered intangible domain (Agnew, 2014). Overall, the electoral dynamic and spaces are generally rooted in the cultural distinctness of places where the constituencies are carved out (Agnew & Muscarà, 2012).

Elections are studied through various academic lenses. It has been an integrated subject matter of different branches of knowledge scattered in political science, political phenomenology, political sociology, political economy, and other anthropocentric disciplines (Biswas & Mondal, 2019). Electoral geography is the sub-branch of political geography; it is comparatively new to analyze the elections. It has significantly provided the spatial turn for the study of elections in democratic spaces. It has contributed more to observing the electoral behavior and its variation among constituencies (Low & Smith, 2013).

In comparison with political scientists, geographers have devoted more of their intellectual resources to understanding spatial dimensions of political systems and staking out the frontiers and boundaries of the field of political geography (Johnston et al., 2020). In a democracy, voting participation reflects the involvement of the individuals in the electoral process (Biswas & Mondal, 2018). Johnston (2005) argues that geography can provide an entirely new dimension to the study of elections. On the other hand, political scientists generally have studied elections without much reference to geographical factors (Johnston et al., 2014). Prescott's understanding of electoral geography is regional delineation with a primary focus on socio-economic variables (Arulampalamet et al., 2009). He has determined that the cartographic method of electoral analysis is helpful to delineate the socio-economic groups under investigation. These groups are located within well-defined geographical areas so that clear association can be drawn, and the various groups exhibit strong support for the parties so that a clear and distinct political space can be displayed.

Objectives

-

To examine the patterns of voting behavior in the Lok Sabha elections from 2009 -to 2019 in Uttar Pradesh.

-

To analyze the causes and factors that have led to changes in the voting behavior of the electorates in Uttar Pradesh

-

To analyze the differences in rural–urban voting behavior in Lok Sabha elections in Uttar Pradesh

-

To analyze the spatial pattern of voter turnout in the Loksabha elections from 2009 to 2019.

-

To analyze changing patterns of voter turnout from 2009 to 2019 Lok Sabha Elections.

Statement of Problem

The current paper aims to analyze the electoral geography of Uttar Pradesh from 2009 to 2019. This aims to investigate the deep spatial structures which evolve out of the mundane electoral outcome. These include the overall big picture of the prevailing political scenario, which also implies the geographies of negotiation between various social groups and regions that produce such an outcome. Lok Sabha election has to be analyzed, and these suggest that various constituencies at different levels of elections would give rise to some patterns and processes. Traditionally, the electoral dynamic and voting behavior of Uttar Pradesh has been an essential ground for research observation. Electoral geographers and political scientists who are academically engaged with the polity of Uttar Pradesh have reflected much about the variants of identity politics rooted in caste, community, and religion influencing the voting behavior of electorates in the state. Ramification `of such spatial interpretations will be judged through various levels from rural–urban, class, caste, religion, and regional basis, and their space relation will also be studied.

Significance and scope of study

The present research is highly significant and valuable in studying the impact of cultural spatiality on the electoral behavior of Uttar Pradesh. The electoral pattern and voting behavior are determined by multiple factors rooted in the state's political culture. This study evolved its theoretical structure while considering culture, social structure, collective memories, populism, and place characteristics as major features influencing the Lok Sabha election of Uttar Pradesh. Shifting of power among political parties and electoral mobilization, campaign, and tactic of political parties for the sake of electoral incentives are observed analytically that represents the electoral dynamics within the cultural framework of Uttar Pradesh. Four consecutive Lok Sabha elections are studied in the case study of Uttar Pradesh. The Time–Space relationship imbibed the social change and stratification as classified features of culture influencing the elections even the ideological entities are diluted. The study has theoretically given the ethnographic and humanistic geography turn with the utilization of spatial inquiry of place.

If output quality is a measure of success, then electoral geography is the success story of modern political geography. Hundreds of studies on the geography of elections, voting behavior, and voter political awareness in various areas of India have been published in the previous two decades. However, there is a scarcity of studies on electoral politics and voting behavior in Uttar Pradesh. As a result, the current research concentrates on electoral politics and the political character of electorates in a regional context. The present study aids in the knowledge of voting patterns, voting behavior, and voting trends in several Legislative Parliamentary elections in Uttar Pradesh and future research on the state's electoral geography. Furthermore, the study would benefit lawmakers, planners, and administrators engaged in formulating developmental plans for the state's citizens. As a result, the research is intended to have scholarly and political significance (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7).

Review of literature

In India, many studies have been conducted on every major election. It can be said that all studies on contemporary Indian politics deal in some ways with elections studies on domestic politics after independence touch upon the electoral process in some way or another. In the broadest sense, those studies might be included within the field of election studies. We need to identify the diversity and pluralism of the Indian electorate and how it gets reflected in the social profile of Indian Legislative bodies. The greater presence of Backward Classes has also resulted in the reformulation of the concerns that were central to these bodies. These aspects are well discussed by McMillan (2012) & Deo (2012). Govinda (2008) Many election studies in India are based on surveys of individual voters looking into various aspects of the actual voting behaviors, political perceptions, party preferences, etc. there are many studies based on the analysis of individual data and case studies of election politics. Kaur (2012) describes that the Indian political scenario has witnessed a paradigm shift over the last couple of years. One of the emerging trends has been the marginalization of the subaltern group, particularly Muslims. The marginalization of Muslims in India has recently been the subject of heated public debate. Nielsen (2011). However, he importantly suggested that a better understanding of how the dynamics of the Muslim vote unfolds in a political context can be evolved only at the state level. Therefore effort has been made to evolve a context-specific understanding of the Muslim vote by comparing the political preferences of the community for different parties in different states characterized by bipolar and Multi-party political competition. Barrett and Kreiss (2019). The implementation of economic policies based on neo-liberalism has reduced India's overall space for Backward Classes and Dali. Alam and Ahmed (2017). People in the majority assume that they are in the minority, making them less likely to speak out about the issues. Albarracín (2018). The mass media are not the most important influence on voting decisions. Family background, economic status, geographical location, and other demographic factors are better predictors of an individual's vote than what he or she reads in the paper or sees on television. Debos (2021) Political cycles examine cycles in policy instruments such as taxes, transfers, and expenditures before an election, while studies on voting behavior examine the effect of policies on the electorate's voting behavior (Fig. 8). Hence the proposed research would focus on the root cause of the Samajwadi Party's and Bahujan Samaj Party's decline and identify the significant causes emerging of BJP in Uttar Pradesh politics (Figs. 9, 10, and 11).

Research methodology

The present research is based upon qualitative methods and secondary sources of data. This paper adopted the mixed strategy for electoral studies in Uttar Pradesh. It analyses the grounded theory of cultural space and places Identity influencing the electoral behavior and its variations across the state. The State of Uttar Pradesh in India is taken as a case study. The observation is ethnographic and phenomenological. This paper derived statistical information about the election and political party performances from the Election Commission of India. Election statistics are represented through Geo-Spatial frameworks such as GIS and Cartographic Techniques. Electoral behavior and voting responses of electorates are interpreted analytically with the theorization of grounded spatiality of cultural identity place. There has been a study of cause-effect relations between the observed independent variables as cultural attributes and dependent variables as voters' responses and electoral outcomes.

Study area

Uttar Pradesh is the largest populous state in India. It is located in the northern part of India. Based on its physiography, the main regions of Uttar Pradesh are the central plains of the Ganga and its tributaries, the southern uplands, the Himalayan region, and the submontane region between the Himalayas and the plains (Singh, 1971). In UP, 80 percent of the population is Hindu by religion (India P, 2011). Ethnic politics in UP, as in much of India, are closely linked to the Hindu caste system. Uttar Pradesh has a total area of 243,246 Km2 sq. Which is 7.33% of the total area of India. 69.72 literacy rate. The sex ratio is 879, and the population density 829. Hindus are the largest religion in Uttar Pradesh, accounting for 79.7%, 159 million people, followed by Muslims with 19.2%. Other religions like Christianity, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists are lower than 1%. In Uttar Pradesh, Brahmin is the highest percentage of the population 10%, followed by Yatavs 11.50%, Yadavs, 8.50%, Thakur, 8.50%, Kurmis, 3%, and others, 24%. Uttar Pradesh is India's largest state and one of the most socially and economically backward in the northern heartland. The state has lagged in economic and social developments, but it is the most prized possession for any political party. Uttar Pradesh is located in the Indo Gangetic basin and accounts for 80 members of Lok Sabha, the highest amongst all the states in India. The party, which wins most seats from this crucial state, only makes it to the center.

Space, place, and electoral behaviour

One of the instrumental functions of political geography is to analyze how the government utilizes space to fulfill its goal (Khan, 2018). Historically, spaces can be used to satisfy political purposes and objectives (Elff, 2009). Spaces are generally viewed as the provider of security and order, economic growth and well-being, and social justice (Dachs, 2017). However, spaces in political geography can also be seen as an element to control the electoral behavior, performance, outcome, and electoral incentives. Among the spaces of various kinds, cultural space has a larger potential to determine electoral behavior (Biswas et al., 2021). The potential control of cultural spaces to the election dynamic may be varied because of the variability of the spatiality of the place and cultural fragments.

The power of cultural spaces as controlling factors of elections can be viewed in the sense of production of "spatial identity," which is the crucial dimension of societal territoriality and ultimately leads to national and cultural Identity (Jones, 2014). However, Soja has linked spatial identity with nations. But people associate this identity with their local constituency level also (Ayyangar & Jacob, 2015). These cultural, spatial units provide a sense of identity and provide a continuity chain with the past. The space–time dimensions provoked individuals to think about who we are? And how have we come to be? Even the spatial root of identity can be seen in the reorganization of territoriality and electoral constituencies. However, the construction of collective imaginations toward a political party or the ideology of a political party has a significant role in electoral behavior. Sometimes collective imaginations produce the identity of the place, and indirectly these identities act as causes for political incentives in favor of a particular political party (Palshikar et al., 2017). However, the role of electronic mass mediation and mass migration produced the imaginations among others and even developed new-deterritorialized identities.

Cultural spaces control the pattern of the political culture of human society. Following the Lucian Pye et al. (2009), political culture is reflected by a collective assemblage of human attitudes, social and cultural beliefs, and sentiments which construct order and provide meaning to a political process. It also shapes the underlying assumptions and rules which govern human behavior in a particular political system (Diamond, 2015). A political culture rooted in the cultural, spatial construct is reflected in a government structure of the state, though it also incorporates the elements of history and traditions. Political cultures matter because they shape a population's political perceptions and actions. Governments can help shape political culture and public opinion through education, public events, and commemoration of the past. Political cultures vary significantly from state to state and sometimes even within a state (Duggan, 2012).

Cultural spaces provide the subjective basis of political identity. Most political parties in a democracy utilize these identities during the election campaign and electoral mobilization (Boykoff, 2008). Even during the political movement, cultural identities are utilized for the accomplishment of political objectives and goals. Congress Party in India has evolved an elaborate culture aimed at protecting Gandhian values. Mahatma Gandhi associated himself with the cultural identity of the Indian landscape. He built an ideal for the nation through cultural gestures, like holding prayer meetings, popularizing Vaishnava Jana to or Raghupati Raghava Raja Ram, and defining Ram Rajya (Vertovec, 2011). The cultural tactic of the Bhartiya Janta Party in its political mobilization utilized at varied scales is an essential example in this context. Everybody seeks power, but the BJP creates cultural reasoning to seek power (Brennan, 2006).

Another dimension of cultural spaces providing the basis for subjective political identities is the trait of "populism" (Hadiz & Chryssogelos, 2017). Populist tendencies are one of the important controlling factors of the electoral behavior of the masses. Populism is nurtured in a definite cultural space. Political leaders utilize the common identities of cultural spaces to relate themselves in the same sense of belongingness to each other.

Politicians need to care about popular culture because it is one of the common bonds that tie increasingly segmented Uttar Pradesh together. Whether you live in western Uttar Pradesh or eastern Uttar Pradesh or in an urban or rural environment, you know the popular culture. A politician who can skillfully navigates popular culture references and his appearance in popular culture venues can increase his appeal to the public. Narendra Modi, for example, has been quite adept in his use of popular culture in three distinct ways (Chhibber et al., 2014). First, he is fluent in the language of popular culture and makes easy references to his T.V. viewing habits, which the media eagerly and lovingly reports. Second, he makes appearances on soft media entertainment shows (Man ki Baat) where he reaches out to targeted sections of the electorate and avoids pesky hardball questions. Third, he uses Bollywood celebrities to campaign for him and raise money (Doron & Raja, 2015).

Politics is organized and manifested in elections at many different places, and places are intrinsically multiscale, constituted by social relations ranging from parochial or local to global. Spatial contexts may matter in both the socialization of voters and mobilization activities undertaken by political parties (Chacko & Mayer, 2014).

Cultural spaces, identities, and elections in Uttar Pradesh

Identity is formed based on multiple markers such as caste, tribe, religion, language, culture, etc. Ethnicity is visible in the voting pattern and the formation of political parties. According to Chandra (2009), the Bahujan Samaj Party in north India is ethnic. The appearance of the Bahujan Samaj Party resulted from an ethnic movement where Dalit and marginalized sections were the prominent supporters of the campaign. The bases of the formation of identities are – culture (language, dress, food, folklores, etc.), history, economy, real or perceived sense of discrimination, and exploitation. Ethnicity is expressed through indicators such as migration, citizenship, protection of identities and culture, and land protection. The victory of regional parties that derive support from different ethnic groups in these areas indicates that ethnicity determines voting behavior (Biswas, 2022).

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has an alliance with the Apna Dal (considered to be the party of the Kurmis) and the Bahujan Samaj Party (assumed to be the party of the Rajbhars). BJP is an alliance in eastern Uttar Pradesh with the Janvadi Party and other minor parties influential among most backward castes such as Lonia, Nonia, Gole-Thakur, Lonia Chauhan, and Dhobhi (Bartels, 2010). The Samajwadi Party is likely to form an alliance with the Rashtriya Lok Dal (Jat Community). The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) strategy focuses on the non-Jatav Dalit votes and non-Yadav backward caste votes to add to their core Savarna (forward caste) vote bank (Jaffrelot, 2015). The BJP offers them organizational representation to appease its savanna base and showcases its commitment toward Brahminical-Hindutva agendas, such as constructing a Ram temple in Ayodhya. As we use it, the term election strategy has three components: alliance behavior, candidate selection, and the election campaign (Heath, 2020).

The Dalits are core supporters of the Bahujan Samaj Party, contesting this election in alliance with the Samajwadi Party. The political arena in Uttar Pradesh resembles a museum of identity, where caste and religion are perpetually in a love and hate relationship. Dalits continue to reject the BJP because of its political culture and social agenda. The resilience of identity politics is even more evident among the Muslims who have supported Congress irrespective of their class to counter Modi's BJP (Sardesai, 2015). The fragmentation of the Muslim votes, strong anti-incumbency sentiments of the Muslims against the national government, and the BJP's alliances with two regional parties draw their support from scheduled castes and OBC.

Congress has declined in support across the state and its inability to convert votes into seats. The Bahujan Samaj Party represents some Dalit groups' significant social and political movements. Still, it has failed to secure the support of the broader population of the rural poor. The Jatav/Chamar caste group makes up more than half of the Dalit population and is found in villages across most. Paris's second-largest group forms just under 15 percent of Dalits, but they are much more geographically concentrated than the Jatavs.

Role of muslims in Uttar Pradesh election

In the last six decades of our independence, many political parties have been using Muslims as an electoral support base. They have done this by holding up the "threat" of the Hindu right. Muslim politics has always been reactive to the dangers posed by the RSS and the BJP, never proactive. They have supported those parties, which promised dynamics structured to give them greater protection (Mitra & Ray, 2019). But, the Muslims charge that such parties have never translated their promises into reality. They feel that unless they have a say in governance, not much will change. The six most popular myths prevalent in Muslim politics in Uttar Pradesh are; (1) The Muslim society is homogenous. (2) Religious leaders are political decision-makers. (3) Muslims are orthodox (4) Muslim society is not rational. (5) Muslim is one vote bank. (6) The Muslim party realizes the Muslim voting paradigm. These are potent myths in politics in the Uttar Pradesh context. But these myths are artificial. The Muslim society is divided into numerous castes. Muslim society is divided between upper caste and backward caste. Muslims too have a fragmented social composition that includes the rich and the poor, the educated and the uneducated, the urban and the rural, the male and the female, Shias and Sunnis, etc.

According to their estimates, Muslims constituted 20–25 percent of the electorate in more than 125 of the 403 assembly constituencies in Uttar Pradesh. In 60 constituencies, the Muslim population is between 35 and 40 percent. The Muslim fronts want to contest 147 seats in the forthcoming assembly elections in UP. The highest Muslim representation was attained in the 1980 UP assembly elections when 53 Muslims were elected and the 1980 Lok Sabha elections when 18 Muslims were elected. Only 4.32% of Muslims were elected in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, clearly indicating that the Muslim community is politically excluded from Uttar Pradesh politics. While most political parties are worried about the emergence of Muslim political fronts, the Muslim community looks at this development as a possibility of acquiring some clout in the state's politics. The new trajectory taken by Muslim politics may enable them to play a more autonomous role in the politics of Uttar Pradesh.

Pasmanda Muslim organizations, "Political agenda of Pasmanda Muslims in Lok Sabha Elections, 2014," is relevant to understanding this multilayered Muslim identity. This declaration not merely addresses the question of Muslim reservation in a nuanced legal-constitutional manner but also establishes a link between the Muslim caste question and the other political issues such as globalization, communalism, internal diversity of social-religious groups, adequate representation of women, and corruption.

Imam Ahmad Bukhari's appeal to Muslims to vote for Congress or the Muslim Majlis-e-Mushwarat suggested that Muslims support "secular" candidates or even Rajnath Singh's meeting with a few Muslim ulemas in Lucknow are relevant examples in this regard. It has also tried hard to slice the Shia vote by promoting Shia clerics such as Maulana Kalbe Jawad Naqvi, who issued a statement extending support to Home Minister Rajnath Singh, the BJP candidate from Lucknow. However, this time around, the saffron party is also benefited from another half of the women Muslim population after the Triple Talaq Bill.

The Muslim vote is a determining factor in 34 out of 80 Lok Sabha constituencies and 130 out of 403 Vidhan Sabha constituencies. The under-representation of Muslims was due to a split vote. In those constituencies with sizeable Muslim populations, the major non-BJP parties tend to give tickets to Muslims, thereby counterbalancing the advantage of the Muslim vote (Asmer Beg, 2017). In 2014, for example, in Moradabad, with a Muslim population of 45 percent, the S.P., BSP, Peace Party, and Congress all fielded a Muslim candidate, securing 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th positions, respectively. In Sambal, with a 45 percent Muslim population, both S.P. and BSP gave tickets to Muslims, who secured 2nd and 3rd positions. In Rampur, with a Muslim population of 49 percent, S.P., Congress, and BSP gave tickets to Muslims, who confirmed the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th positions, respectively. In Amroha, with a 48 percent Muslim population, S.P. and BSP gave tickets to Muslims, who secured 2nd and 3rd positions, respectively. In Saharanpur, with a 39 percent Muslim population, both the Congress and S.P. passed tickets to Muslims, who secured 2nd and 4th positions, respectively. In Kairana, with a 38 percent Muslim population, both the S.P. and BSP gave tickets to Muslims, who secured 2nd and 3rd positions, respectively. In Meerut, with a 33 percent Muslim population, BSP, S.P., and Congress all gave tickets to Muslims, who secured 2nd, 3rd, and 4th positions. In all the above constituencies, BJP candidates emerged victoriously. The presence of several Muslim candidates in a constituency can lead to a split in the Muslim vote and the defeat of Muslim candidates, often to the advantage of BJP candidates. The BJP did not field any Muslim candidates but won in at least 21 constituencies where the Muslim community's numbers were decisive. So these factors positively impact the overall performance of the BJP in the Loksabha elections. But the 2014 elections pushed Muslims back to the old discourse of 'survival.' They seem to be moving from powerlessness to hopelessness (Michelutti, 2020).

In the past two decades, Muslim voters have chosen different parties in different states: the CPI(M) and AITMC in West Bengal, the regional Samajwadi Party (S.P.) in Uttar Pradesh, the RJD in Bihar, the DMK party in Tamil Nadu, and the Congress in other parts of the country. So the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), led by Owaisi, wants to end the "slavery" of Muslims in the hands of the Samajwadi Party (S.P.), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), and the Congress, which had been using them as their "vote bank.

The voting behavior of Muslims is influenced primarily by two factors—the nature of political competition and choices available in the state and the size of the community. In the constituency where electoral contests are largely bipolar and between the Congress and the BJP, Muslim voters tend to favor the Congress, something not unexpected or unnatural. Muslims see the BJP as a party that threatens their interests. But Muslim votes begin to get fragmented as we move to a political terrain where the community has some choice. However, Muslim votes get much more fragmented with multiple political choices.

To conclude, what shapes and reshapes Muslim politics in Uttar Pradesh largely remains in speculation. This is a major finding of this paper, which could be applied all over India. Muslim Community is an important organ of Indian society; their political inclusion is the basic challenge before Indian democracy.

The electoral dynamic of Urban and rural spaces of Uttar Pradesh

In India, voters live in villages, small towns, and metro politician cities. Although over 70 percent of the total population lives in rural areas, the proportion of the people living in urban areas is continuously increasing, and that of rural areas is declining. A place can be conceptualized in a variety of ways. However, from the political point of view, the construction of political space in terms of neighborhood region, and state, could be useful, especially in the Indian context (Jaffrelot & Kumar, 2015). It is possible to argue that residents of a particular geographical region within a state may develop some common identity predisposing them to vote in a specific way compared to the other areas (Vaishnav, 2019). In rural areas, family or neighborhood could be the most influential site of political socialization and might have an essential bearing on political orientation (Devika & Thampi, 2011). But in cities and especially megacities, educational institutions and workplaces may play an important part in political direction.

On the other hand, the political party's actors would try to mobilize electors in a particular constituency, for example, rural and urban-based on issues relevant to the given constituency. Economic class education and media exposure play a significant role in producing various forms of spatial politics (Brass, 2005). The rural and the urban are discursively formed entities that need to be seen in relation to their constitutive multiplicity. Thus it is imperative to unpack the sociology of rural–urban to understand broader political implications (Dutta, 2012).

However, political mobilization based on media intervention has caused identity formation. The role of social media, electronic and print media, and news content, are continuously shaping the political imaginations of electorates equally among rural and urban masses. A newer form of political socialization is characterized that is not space-bound influences the urban and rural voters. The centrality of an electoral campaign by the media wing of political parties drives the electoral psychology and, ultimately, electoral behavior of the masses (Michelutti & Heath 2013).

The electoral patterns in Lok Sabha and state assembly elections reflect perceptible differences and variations across regions, groups, communities, and constituencies. One such significant variation is found in the urban and rural voting and party campaigning patterns. The rural voter turnout in Uttar Pradesh stood at 58.5 percent compared to 54.7 percent in urban localities. The difference also lies in party support in urban and rural areas, issues of campaigning, and, finally, strategies to connect with rural and urban masses. Is the recent Lok Sabha election also a testimony to such variations? Or has the gap reduced due to the predominance of other kinds of polarization, especially religion?

The control over collective imaginations through agencies, especially the media, is significant in the context of recent general elections. Bharatiya Janta Party was more potentially involved in capitalizing on the media power for electoral gain. The collective imaginations were shaped in terms of sentiments attachment towards the Bhartiya Janta Party. We can see the trend in the 2009 general election; non-BJP political parties mostly dominate the urban constituencies. In terms of urbanization on a community basis, we can observe that the Muslim proportion residing in urban centers varies from 36–40 percent. Traditionally, the electoral behavior of Muslims is generally in opposition to BJP. Hence in the 2009 election, about 13 urban constituencies were represented by the Non-BJP party. However, apart from the influences of the voting line, other factors like anti-incumbency to Congress, the political strength of S.P. and BSP, and caste-based identity politics have also controlled the 2009 general elections. Though, in 2014, we can observe the larger electoral victory of the BJP dominating rural and urban constituencies in Uttar Pradesh. Only those seats traditionally belonged to the leadership stature of INC, S.P. has been preserved like Azamgarh, Amethi, Faizabad, Rai Bareilly. Even the BSP has not won a single seat from rural or urban places. The electoral dynamic of the rural–urban divide or separate rural–urban mobilization has not been experienced in the electoral mobilization. The central leadership of Narendra Modi and politics of populism helped by collective imaginations have a more significant say in 2014 and 2019. Even in the 2019 general election, BJP has won, but S.P. and BSP's political alliance has also tried to re-produce their politics based on OBC and Dalit alliance. However, the control of media, the popularity of Narendra Modi, and sentiment-based collective identities on nationalism has overpowered the masses, ultimately leading to the BJP in the 2014 and 2019 general elections.

Social scientists, philosophers, and policymakers have struggled to explain why citizens vote and why turnout varies extensively within and across countries. Poor’s in India tends to vote more than the middle class or the rich, villages more than cities, and lower castes more than upper castes (Yadav & Palshikar, 2009). Hence, the failure of democratically elected governments to provide adequate services to the poor cannot be explained by a lack of participation of the poor in the political process—the question of more significant political participation from somehow marginalized social groups and rural areas population. Middle-class urban population, traditional, local factors replaced to national factors, migrants population, or even urban population identity of a place is diluted. Local business community small-scale shopkeepers oriented and earlier decide their votes. Political mobilization will not affect or change their prior decision compared to the voters of rural areas.

Patterns of voting behaviour (Tables 1, 2, and 3)

Our study deals with the spatial and temporal variations of electoral behavior in the three Lok Sabha elections in the political space of Uttar Pradesh. It covers the elections of 2009, 2014, and 2019. The main focus of this paper is on the identification, description, and analysis of patterns of participation and associated parameters with the help of electoral data, maps, and empirical observations. The first impression of voting behavior depicted in the 2009 election is the demarcated line as the pre-BJP and Post BJP phases. The degree of success of a political party is a measure to be taken as the proportion of seats won by it to the total number of seats contested. Hence, we can easily observe that in the 2009 Lok Sabha election, BJP won 10 out of 80 seats, and the vote percentage was 17.5; in 2014, elections BJP got 73 out of 80, and the vote percentage was 43.3, and in the 2019 election, it gained 64 out of 80, and vote percentage was 50, so the BJP party performance is outstanding. Slightly seat sharing is declined, but the vote share is increasing, and this result shows that Modi's performance is growing in all sections of the society. BJP got 14 seats out of 17 reserved seats in the 2019 Loksabha elections and BSP 2 and ADS 1. What happened to electoral politics? How has BJP situated its rank higher than other political parties? The answer lies in the Pan Indian reflection, especially the north Indian belt collective imagined, populist, sentiment-based imaginations in favor of BJP and against the INC. Indian National Congress has come into defensive mode in a rapid mobilization and very popular tendencies of Narendra Modi's leadership (Haynes, 2020).

BJP has planned town halls targeted at women and outreach via smaller groups. Benefits received from central schemes like Jan Dhan Yojana, Ujjwala LPG scheme, and Swachh Bharat Abhiyan are being iterated to women voters. Another scheme that got BJP connected to the voters was the Ayushman Bharat scheme. PM Modi launched the Ujjawala scheme, providing free LPG connection to families without cooking gas access. The Modi government claimed to have distributed more than one crore of LPG connections in UP to poor households and publicized it to women's empowerment. The participation of women voters has been higher in the past two elections. The female turnout was five percentage points higher than the male turnout in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and seven percentage points higher in the 2017 assembly elections. The importance of the women's votes gains more salience in this election.

The attack on INC, utilization of mass media and populist scheme, creation of miss recognized enmity to the minority class, religion centric nationalistic agenda were the important electoral tactics adopted by BJP in the electoral campaign.

In terms of loss of sub-regional political leadership of National Lokdal, communal riots in the selective district of western Uttar Pradesh in 2012–13 have caused voters' polarization, and BJP subsequently replaced the Indian Lokdal. This polarization effect was seen in the 2014 general election (Chacko, 2020). In the absence of proper, functional, and strong opposition, BJP has filled the vacuum against INC in India. BJP has successfully captured the unsatisfied sentiments in favor of it.

In this election, the performance of the BJP was highly impressive. There was a landmark increase in both the spatial support and strength of the party. The average vote share of the BJP party was 41.37 percent. The party got very high approval from 56 constituencies and very little support from 8 constituencies. In the 2019 elections, the handful of seats lost by the BJP in rural Uttar Pradesh reveals voter disenchantment due to agrarian distress. The support for the party was significant (more than 50 percent) in Pilibhit, Lalitpur, Hamirpur district, and Gautam Budh Nagar. Thus the social engineering of the BJP under the leadership of Amit Shah leads to expanding its territorial strength. Shah was an outsider to UP; he was responsible for managing his job with surgical precision, from candidate selection and arranging funds to election booth management to conducting hi-tech election campaigns (Harriss, 2015). He gave importance to panchayat level BJP leaders who had been visible in every political party activity in their constituencies in the past couple of years. He provided detailed guidelines on conducting election campaigns and how resources had to be collected and distributed by adjacent constituencies. The 80 Lok Sabha seats were divided into 21 clusters of three to five seats. These clusters were divided into eight zones, and all zones were under the single umbrella of the state unit. A separate strategy for mobilization was devised for each cluster, including drawing people from a radius of 175 km for Modi meetings.

At least three significant issues preceded the Lok Sabha elections in UP. One of them was the Muzaffarnagar communal riots, which affected the social climate of the state and its effect on the image of the Samajwadi Party government (Sinha, 2016). The management of the riots and the whole post-riot relief camps were not appropriately managed, which angered both Muslims and the Hindus Community. Muslims accused the government of blatantly siding with Hindus, and Hindus accused the government of not paying attention to riot victims. The self-proclaimed secular parties exploited this position of the Muslim voter. Security of life and property was Muslims' primary concern, and the S.P. and BSP competed with each other in claiming to have made them feel secure. Muslims did not have the bargaining capacity to demand their political seat share and, therefore, got nothing substantial in return. Mulayam Singh was able to position himself as the savior of Muslims and, therefore, get a large proportion of their votes (Jaffrelot & Verniers, 2020). Finally, that opportunity was put to the best use when Modi decided to make Varanasi his parliamentary constituency giving the people hope of development based on the Gujarat model (Rehman, 2018). A combination of these issues created an electoral turf favorable to the BJP in UP, making the task of Amit Shah, its leader in charge of the state, a little easier (Chakraborty & Pandey, 2008).

BSP is the second-largest party in Uttar Pradesh's recent Loksabha elections under the leadership of Mayawati. The BSP got winning ten seats. In the 2009 Loksabha election, BSP won 20 seats out of 80 seats, and the vote percentage was 27.4; in 2014, elections won 0 out of 80, and the vote percentage was 19.8, and in 2019 election won 10 out of 80, and vote percentage was 19.4, so the BSP party's performance is stagnant due to the traditional Dalit and Muslim voters. Some of the schemes Mayawati launched significantly benefited Dalits. For example, the Ambedkar Village Scheme (AVS) special funds for socio-economic development to villages that had a 50% scheduled caste (S.C.) population. The Dalits of these villages received special treatment roads, hand pumps, houses, etc., which were built in their neighborhoods (Jaffrelot & Kumar, 2015). Due to these scheme benefits, the core heart of Dalits enthusiastically called her government their own. But in the 2019 Lok Sabha Election, Caste-based parties were numbered in UP, and Chief Minister Mayawati's "social-engineering" had failed. The failure of a BSP-SP alliance in UP did not work at the ground level because caste has come to dominate politics; indeed, caste boundaries are more important than the Hindu-Muslim boundary (Sharma, 2015).

The congress party campaigned on the slogan NAV (N Nyaya, A- Adhikaar and V- Vikas). Uttar Pradesh 2019 Lok Sabha election promised strong leadership and better governance and made towns and cities in Uttar Pradesh centers for economic and industrial growth. Congress also promised to make the state a leader in agriculture, provide a good livelihood for farmers, create more than 20 lakh jobs, and open more intermediate colleges. The party promised free electricity connections for all below the poverty line. The party also stressed the issue of women's empowerment. Congress also promised a minority quota within the OBC quota. The party also promised one cow to all BPL families and provided free scooty for girls and free computers, mobiles, and laptops for students.

Growing poverty, unemployment, and neglect of agriculture became the themes in the Congress campaign. Terming the claim of the NDA that it brought about development as an eyewash aimed at deceiving the people, Rahul Gandhi, the Congress president, said: "If there is development, it should reflect on the common man's face. "it is not." Chidambaram criticized BJP's India Shining and Feel Good campaign as 'cynical and humiliating'(Rajadesingan et al., 2020). Congress desperately tried to project an image of the pro-poor party. But this agenda did not work at the ground level due to religious beliefs. Finally, it may be a source of social and political values and attitudes that, in turn, influence political behavior. Political parties frequently play an essential role in generating relationships between the dimensions of religion and political behavior. Although Congress party's seat-sharing did not increase, vote share was constant as in the 2019 and 2014 elections with minimum variation, respectively. INC has lost its 18.3 percentage votes in the 2009 election, reflecting the decreasing political value of INC.

The CSDS prepoll survey for U.P held in December 2016 shows that voters lookout for the most critical issues such as unemployment, price rise, Crime, Riots, and Farmer suicides during the elections (Heath & Kumar, 2012). However, some issues like triple talaqs, demonetization, anti-incumbency, and surgical strikes influenced the voters (Harriss et al., 2015). The composition of the 2017 election retains its traditional upper-caste bias and reflects the commitment to inclusion through the promise of good rapid governance development and Modi's Campaign. The BJP expanded its influence in urban areas and rural areas. The party performance, spatial strength, and votes between the winner and leading candidates have massively increased. The main reason for Bhartiya Janta Party's remarkable victory was the loss of support for the incumbent Samajwadi Party from the upper caste and Dalits. Even core voters were not satisfied with the coalition between Indian National Congress and the Samajwadi Party and shifted their votes to Bhartiya Janta Party.

However, Akhilesh Yadav, the new Chief Minister, took no steps to fulfill these promises, nor did he initiate any policy-related schemes that could address the social and economic backwardness of the Muslim community (Ahmed, 2020). One of the significant promises, seen as both ambitious and contentious, was that when the S.P. came to power, it would withdraw cases against Muslim youth who were, in the eyes of the Muslims, wrongly arrested on charges of terrorism. So the Muslim voters affect the overall performance of S.P. in UP politics. Firstly, the so-called secular parties treated Muslims as their vote bank but did nothing to promote their well-being.

Finally, the state's people had seen the two models of governance and development. One was the models of governs and development. One was the Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi national management and development model for 10 years full of scams, political corruption, rising prices, and misuse of power. The second was the Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav governance model that smacked incompetence, lack of vision, blatant casteism, politics, Muslim appeasement, and a deteriorating security environment (Lal et al., 2015). The people were not satisfied with the United Progressive Alliance government at the center and the S.P. government in the state (Ranco, 2007). When these two models were compared with the Gujrat model of development, Hindutva agenda, and Rammandir issues, voters thought the Modi Gujrat model was ideal.

Tables 4, and 5 shows the Constituency-wise voter turnout in the Lok Sabha election in Uttar Pradesh from 2009 to 2019. It reveals that the voter turnout is high in the 2019 Lok Sabha Election compared to the 2009 Lok Sabha Election. In 2009, 2014, and 2019 Lok Sabha Election, Agra, Allahabad, Kanpur, Lucknow urban constituencies had the lowest voter turnout, and Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Kairana, Mainpuri, Jhansi constituencies where rural voters are more in number, had the highest voter turnout. In Urban areas, people are not mobilized enough for voting; even they are not intimately related among voters and political party cadres. Urban people get benefits from each of the governments. So at the time of elections, urban people celebrate holidays; even lesser participation is there in the election process. But in rural constituencies, relationships among voters and political party cadres are intimate. It is one of the most important reasons for higher voter turnout in the rural constituency (Choudhary et al., 2020).

The middle-class population and female voters' participation are also lesser in the electoral process in urban areas though educationally, these classes are richer than in rural areas. The exposure of the rural population, even male and female, to the outside within the vicinity of the village is more because of the cohesive forces and emotional quotients of rural voters. Sometimes, rural voters are potentially more mobilized through local cadre through economic incentives. Political parties focus more on such populations who are considered honest, loyal, and dependable and can be easily converted into voting (Farooqui, 2020).

Relationship between scheduled caste population and voter turnout

Null Hypothesis (H0)

There is no significant statistical relationship between the scheduled caste population and voter turnout in the 2009 and 2019 Loksabha elections.

Hypothesis (H1)

The scheduled caste population is positively related to the voter turnout rate. The scheduled caste population always affected the voter turnout.

The correlation analysis Tables 4 and 5 reveal that Pearson's correlation coefficient between schedule caste population and voter turnout is 0.509 in 2009 and 0.603 in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Since the value of r in the 2009 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections is close to 1.0, there is a strong positive correlation in both Lok Sabha elections. The relationship between the scheduled caste population and voter turnout has positively correlated in the 2009 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections. The scheduled caste population always affected the voter turnout. It shows that a higher percentage of the scheduled caste population region has a higher voter turnout rate during both Lok Sabha elections. Both the table depicts that value of p (= 000) and (= 000) respectively is less than 0.01, so the correlation is significant at 1% level of significance. Therefore, the null hypothesis of the study presented as there is no statistical relationship between the scheduled caste population and voter turnout in the 2009 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections is rejected. So we can confidently say with 99% confidence that there is a positive statistical relationship between scheduled caste population and voter turnout in both the 2009 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections. Therefore first proposed hypothesis is accepted.

Figure 8 CPV- Consistent pattern of voting means the repeated fielding of one candidate for the same political party in elections. ICPV- Inconsistent pattern of voting means fielding of one candidate for a particular party for once or twice. ICPV and IICPV -Initially consistent and Initially inconsistent pattern of voting. Reflect constituent pattern of voting for a definite period of time and in the Inconsistent pattern of voting for an indefinite period of time.

Figure 12 Explained Constituency-wise changing pattern of voter turnout in the Lok Sabha Election in Uttar Pradesh from 2009 to 2019. It expressed that in the 2009 Lok Sabha election, voter turnout was 48.04, and in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, voter turnout was 59.12. It shows that the changing pattern of voter turnout has decreased, i.e., 11.05 percent from 2009 to 2019. Another important thing is those Constituency victories by BJP Party are Higher Changing Pattern of Voter Turnout and those Constituency victories by INC, BSP, and S.P. common changing pattern of voter Turnout

Popular planning and yojana of BJP govt were rural-centric, target voters are from a marginalized group of society, women, especially the socially and economically weaker section of society. Jan Dhan Yojana, Ujjawala Yojana, sense of self-respect, Swachta Mission, Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao, rural psychology on Hindu religion, Free ration and Free internet from Jio (Kumar, 2020).

Conclusion and discussion

In the analysis of electoral behavior in general elections of 2009, 20,014, and 2019 in Uttar Pradesh, it can be observed that produced spatiality of place and collective imaginations have larger control over the electoral behavior. In populist, religion-centric mobilization, and social-structure-based campaigns, the emerging binary of electoral politics leads to bipolar electoral tendencies. The political parties generally utilize the already evolved "sentiments" of ourselves and "others" to transform into pocket votes. The general features of voting behavior are shifting voters' responses in favor of bipolar adjustment towards Bhartiya Janta Party from Indian National Congress, the Samajwadi Party, and the Bahujan Samaj party of India. The political parties of INC, S.P., BSP, percentage vote share has been decreased. In the same way increase in the vote percentage of the BJP was recorded as a positive gain. This increasing vote share of the BJP indicates the populist encroachment of the electoral mindset. The leadership of Narendra Damodar Modi has attracted more individuals. The cultural spaces of Uttar Pradesh are very feasible for the electoral mobilization of religious/communal sentiments. The already existing social atmosphere favors the campaign. These characteristics of electoral behavior demarcate the vote transfer features. The inferences can be drawn that the caste-based party arrangement of S.P. and BSP positioned against the Indian National Congress and chose BJP to tackle caste politics in the state. The identity of place (Genre de loci) and cultural milieu still persists that can be observed in the suitable political position of Yogi Adityanath in state politics and general elections. The Pan Indian issue or national identity issue, including the Ram Mandir Babri Masjid issue of Uttar Pradesh, has become the larger political agenda that caused polarization. It generally penetrated the voters' perception in Uttar Pradesh. Recently, BJP has successfully mobilized the marginal classes of society. The caste issue has emerged at the electoral level. In the 2019 general election, BJP has utilized the caste/marginality factor for electoral gain as BJP has concentrated on the marginal castes of Uttar Pradesh and won 14 Lok Sabha seats out of 17 reserved for the scheduled castes in 2019. Caste-based mobilization seems to be the emerging tendency for the electoral incentive of political parties in Uttar Pradesh. However, caste-based mobilization has always been an electoral tactic in the local elections of Uttar Pradesh. One of the important features of political mobilization by the BJP is an alliance with the local caste leader such as Nishad Party, Rajbhar-leader (Om Prakash Rajbhar), and in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. BJP has developed local relations with the masses in various constituencies with other local caste leaders.

Policies like the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, Skill India, Make in India, Stand-up India, and Start-up India, for example, are some of the policies, the names of which carry a certain political value. The common element among these policies is linking the country's name with the policies. This, however, is not an invention of the BJP government. There is precedent for majority governments adopting these strategies to influence a larger number of voters or manipulate public opinion in favor of their government. The BJP and allies enjoy more pronounced support among Ujjwala, Awas Yojana, and Jan Dhan beneficiaries. These are all schemes for which voters attribute credit to the central government. However, among the MGNREGA beneficiaries, the BJP gets less than its average support. Programs such as the Swachh Bharat Mission, incorporating principles of dignity and access via Izzat Ghars, especially for women, and Ujjwala schemes that facilitate access to rural infrastructure and assets to women. Financial inclusion schemes such as Beti Bachao, the PM Jan Dhan, the Sukanya Samridhi Yojana, and the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana have possibly reaped exponential dividends for the BJP this election. The BJP revived its historic promises to build the Ram Mandir at Ayodhya. The BJP claimed that they would make Uttar Pradesh the best state in the country. The other major promises made by the BJP were better governance to end corruption, create unemployment benefits, better employment opportunities, and better health facilities. The BJP promised greater industrialization to reduce the number of people leaving the state to find jobs on the economic front. It has brought radical transformation in the lives of the poor, plugging leakages through direct benefit transfers. The various gendered schemes like Ujjwala, Beti-Bachao, Beti-Padhaao, Nai Roshni for minority women, and the 'toilets for women' have completely revolutionized women's lives and the Triple Talaq that has given a new lease on life to Muslim women in particular. With these schemes, BJP got a lot of support from women, the middle class, and Dalit voters, who gave a massive victory in 2014, 2019 Lok Sabha, and the 2017 Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh.

However, one significant trend that has emerged in contemporary general elections, particularly during the 2014 and 2019 general elections, is visibly fewer influences on the rural–urban divide. The cultural milieu of daily life, geography, and urban and rural life have not affected the voters differently. The imagined electoral identities of "rural"- urban "voters" were under the same shadow. BJP has beautifully captured the dominant voter's response. However, the bifurcation and division of voters among opponents like S.P., BSP, and INC in the constituencies have also favored BJP.

Nonetheless, "class," a dominant political attribute for electoral gain, has been central during the Congress regime. This study has further revealed that in Uttar Pradesh, caste as an element of social mobilization has always been present but was remained submerged by an upper-caste doctrine of "class." The Parliamentary seats demographically dominated by S.C. have traditionally been won by S.P. and BSP and in the 2004 and 2009 general elections. BSP desperately tried to project an image of the pro-poor party's measures (Bijli, Sadak, and Pani) to gain a support base among the lowest strata of rural society. The land-less population and the poor strata of society belong principally to the scheduled castes, other backward castes, and the minorities (altogether constituting 67.7% of the rural population in Uttar Pradesh). The more significant turnout in elections is because of the active participation of these communities. That shows the electoral division in larger voting percentages from the constituencies. The rationale for the increasing percentage vote share of BJP and winning probability of BJP from these seats are because rural daily life geography is dominated by religious sentiments, caste stratification, and unflinching faith in a tradition that is the ground of electoral mobilization of BJP. The effective utilization of "collective imaginations" through mass media in favor of the BJP is an important process. With the decline of the Mayawati Dalit political factors in the state, caste will finally be able to play an essential role in the politics of postcolonial Uttar Pradesh. The tendency can be correlated with the decline of INC, S.P, and BSP political mobilization in other northern states of India, leading to the strength of caste and religious mobilization of voters.

The "populism" politics has drastically made the route in Uttar Pradesh politics. The ultimate popularity of Narendra Modi at the national level has undoubtedly influenced the elections in Uttar Pradesh, just like in other states. Though, in 2014 and 2019, the electoral behavior of Muslims has been the pattern against BJP. The S.P. and BSP have won more seats in the constituency where Muslims are demographically well represented. In the same way, in the constituency where the Muslim and Dalit population is in a balanced situation, the BJP has won many seats.

Hence, the current political situation in Uttar Pradesh is characterized by the rapid deterioration of Dalit political parties. The mighty Dalit and socialist party that controlled every sphere of social activity while functioning within a democratic set-up in the state experienced electoral losses. The issue of Ram Mandir and Babri Masjid may be counted as one of the reasons for the replacement of S.P. and BSP with BJP, but the deep-rooted causes may be located in the caste, religion, populism, and emerging sentiments of citizenship issues. There was a polarization of votes on religious lines, and the BJP received higher votes.

The upcoming state legislative election that is scheduled in the year 2022 seems to be one of the grounds to examine the electoral behavior of voters with due response to inculcate the feelings about the National Register of Citizenship act and Citizenship Amendment Act in the context of bordering state. BJP has special attention towards the Uttar Pradesh election, where its strategy is imbibed for the 2024 general election. The question here is how electoral spaces of Uttar Pradesh are created? How will voters be mobilized in favor of different political parties? The electoral behavior of previous general elections reflects the tendencies of shifting of bipolar adjustment of voter response in which Priyanka Gandhi led the Indian National Congress, and Bhartiya Janta Party has emerged to be a significant voice. Though at the state level, Mayawati Akhilesh Jadav may have a positive gain due to regional populism and local place identities mobilization in the general election.The same demographic proportion of Uttar Pradesh may experience other issues of electoral mobilization that will include religious sensitization, emerging national issues, development, Pan India populism and iconize politicization. The outcome would be an emergence of bi-polar political groups favored by distinct demographic strata based on S.P., BSP, INC, and BJP. Despite it, the Congress Party tries to revive the state unit under the leadership of Priyanka Gandhi. In recent years, Congress leadership has improved internal discipline and function.

The study shows that the party has played a central role in this construction due to its practice in political mobilization and its conduct and government policy. It has benefited thousands of Dalits through reservations and village programs. In the present political conjuncture of Uttar Pradesh and India more generally, targeting particular caste groups for political mobilization remains an attractive prospect for any party or movement.

Having polarised the electorate along caste and community lines, regional parties can now overcome their narrow sectarian bases and become principle parties. Practically, political parties cannot put forward any ideology or program of development, creating widespread apathy and dissatisfaction among the public. Consequently, parties today cannot perform the functions of interest articulation and aggregation necessary for forming a stable government within a parliamentary democracy. At independence, UP was described as one of the best-governed provinces within the country. Ineffective parties and weak political leadership have been responsible for the steady erosion of political and administrative governance standards in UP during the last decade; two-fold reform is required: parties must eschew identity politics in elections and reform their internal functioning. Principled parties with firm ideological moorings and inner-party democracy are more likely to behave properly and provide responsible governance when in power. It would improve the moral quality of leadership, strengthen parties' internal structure, and raise the level of public discourse in the state.

Coalitions have played a vital role in the unexpected BJP victory in the 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections in Uttar Pradesh. The BJP followed the Congress strategy of mobilizing OBCs, Dalits, and Adivasis, sponsoring aspirants from these communities as party candidates. The rise of the BJP to political dominance results from multiple external and internal factors to the party. The decay and decline of the once-dominant Congress and regional parties and the failure of the non-Congress non-BJP parties to forge stable governments are the external ones. BJP's innovative political strategy to adapt itself to the changing times and the popularity of Narendra Modi are internal ones.

References

Agnew, J., & Muscarà, L. (2012). Making political geography. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Agnew, J. A. (2014). Place and politics: The geographical mediation of state and society. Routledge.

Ahmed, H. (2020). Politics of constitutionalism: Muslims as a minority. In Minorities and populism—Critical perspectives from South Asia and Europe (pp. 95–106). Springer.

Alam, M. S., & Ahmed, H. (2017). Place, politics and voting: Lok Sabha election 2014. In Electoral politics in India (pp. 230–240). Routledge India.

Albarracín, J. (2018). Criminalized electoral politics in Brazilian urban peripheries. Crime, Law and Social Change, 69(4), 553–575.

Arulampalam, W., Dasgupta, S., Dhillon, A., & Dutta, B. (2009). Electoral goals and center-state transfers: A theoretical model and empirical evidence from India. Journal of Development Economics, 88(1), 103–119.

Asmer Beg, M. (2017). The 2014 parliamentary elections in India: A study of the voting preferences of Muslims in Uttar Pradesh. The Round Table, 106(5), 567–576.

Ayyangar, S., & Jacob, S. (2015). Question hour activity and party behaviour in India. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 21(2), 232–249.

Barrett, B., & Kreiss, D. (2019). Platform transience: Changes in Facebook’s policies, procedures, and affordances in global electoral politics. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–22.

Bartels, L. M. (2010). The study of electoral behavior. In The Oxford handbook of American elections and political behavior, pp. 239–261.

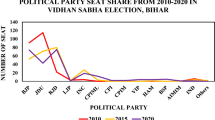

Biswas, F. (2022). Electoral patterns and voting behavior of Bihar in Assembly elections from 2010 to 2020: A spatial analysis. GeoJournal, 1, 1–35.

Biswas, F., & Mondal, N. A. (2018). Voting behavior of different socio-economic groups: A case study in Tehatta of Nadia district. West Bengal, 6(10), 1906–1913.

Biswas, F., & Mondal, N. A. (2019). Voters, significant issues and political party: A case study of Nadia district of West Bengal. Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 10(1), 15–23.

Biswas, F., Khan, N., & Ahamed, M. F. (2021). A study of electoral dynamic and voting behavior from 2004 to 2019 in Lok Sabha elections of West Bengal. GeoJournal, 25, 1–27.

Boykoff, M. T. (2008). The cultural politics of climate change discourse in U.K. tabloids. Political Geography, 27(5), 549–569.

Brass, P. R. (2005). Language, religion and politics in North India. iUniverse.

Brennan, T. (2006). Wars of position: The cultural politics of left and right. Columbia University Press.

Chacko, P. (2020). Gender and authoritarian populism: Empowerment, protection, and the politics of resentful aspiration in India. Critical Asian Studies, 52(2), 204–225.

Chacko, P., & Mayer, P. (2014). The Modi lahar (wave) in the 2014 Indian national election: A critical realignment? Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 518–528.

Chakrabarty, B., & Pandey, R. K. (2008). Indian government and politics. SAGE Publications India.

Chandra, K. (2009). Why voters in patronage democracies split their tickets: Strategic voting for ethnic parties. Electoral Studies, 28(1), 21–32.

Chhibber, P., Jensenius, F. R., & Suryanarayan, P. (2014). Party organization and party proliferation in India. Party Politics, 20(4), 489–505.

Choudhary, B. K., Singh, A. K., & Das, D. (Eds.). (2020). City, space and politics in the global South. Routledge.

Dachs, H. (2017). Regional elections in Austria from 1986 to 2006. In The changing Austrian voter (pp. 91–103). Routledge.

Debos, M. (2021). Biometrics and the disciplining of democracy: Technology, electoral politics, and liberal interventionism in Chad. Democratization, 28(8), 1406–1422.

Deo, N. (2012). Running from elections: Indian feminism and electoral politics. India Review, 11(1), 46–64.

Devika, J., & Thampi, B. V. (2011). Mobility towards work and politics for women in Kerala state, India: A view from the histories of gender and space. Modern Asian Studies, 45(5), 1147–1175.

Diamond, E. (2015). Performance and cultural politics. Routledge.

Doron, A., & Raja, I. (2015). The cultural politics of shit: Class, gender and public space in India. Postcolonial Studies, 18(2), 189–207.

Duggan, L. (2012). The twilight of equality? Neoliberalism, cultural politics, and the attack on democracy. Beacon Press.

Dutta, S. (2012). Power, patronage and politics: A study of two panchayat elections in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 35(2), 329–352.

Elff, M. (2009). Social divisions, party positions, and electoral behaviour. Electoral Studies, 28(2), 297–308.

Farooqui, A. (2020). Political representation of a minority: Muslim representation in contemporary India. India Review, 19(2), 153–175.

Govinda, R. (2008). Re-inventing Dalit women’s identity? Dynamics of social activism and electoral politics in rural north India. Contemporary South Asia, 16(4), 427–440.

Hadiz, V. R., & Chryssogelos, A. (2017). Populism in world politics: A comparative cross-regional perspective. International Political Science Review, 38(4), 399–411.

Harriss, J. (2015). Hindu nationalism in action: The Bharatiya Janata Party and Indian Politics. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 38(4), 712–718.

Harriss, J., Sinha, A., Wyatt, A., & Singh, S. (2015). Indian political studies: In search of distinctiveness. Pacific Affairs, 88(1), 135–144.

Haynes, J. (Ed.). (2020). Politics of religion: A survey. Routledge.

Heath, O. (2020). Communal realignment and support for the BJP, 2009–2019. Contemporary South Asia, 28(2), 195–208.

Heath, O., & Kumar, S. (2012). Why did Dalits desert the Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh? Economic and Political Weekly, 1, 41–49.

INDIA, P. (2011). Census of India 2011 provisional population totals. Office of the registrar general and Census commissioner.

Jaffrelot, C. (2015). The modi-centric BJP 2014 election campaign: New techniques and old tactics. Contemporary South Asia, 23(2), 151–166.

Jaffrelot, C., & Kumar, S. (2015). The impact of urbanization on the electoral results of the 2014 Indian elections: With special reference to the BJP vote. Studies in Indian Politics, 3(1), 39–49.

Jaffrelot, C., & Verniers, G. (2020). A new party system or a new political system? Contemporary South Asia, 28(2), 141–154.

Johnston, R. (2005). Anglo-American electoral geography: Same roots and same goals, but different means and ends? The Professional Geographer, 57(4), 580–587.

Johnston, R., Shelley, F. M., & Taylor, P. J. (Eds.). (2014). Developments in electoral geography. Routledge.

Johnston, R., Manley, D., Jones, K., & Rohla, R. (2020). The geographical polarization of the American electorate: A country of increasing electoral landslides? GeoJournal, 85(1), 187–204.

Jones, M., Jones, R., Woods, M., Whitehead, M., Dixon, D., & Hannah, M. (2014). An introduction to political geography: Space, place and politics. Routledge.

Kaur, A. (2012). Issues of reform in electoral politics of India: An analytical. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 1, 167–174.

Khan, M. S. (2018). Electoral behaviour in Bangladesh: 1991–2008 (No. Ph.D). Deakin University.

Kumar, S. (2020). Verdict 2019: The expanded support base of the Bharatiya janata party. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 5(1), 6–22.

Lal, D., Ojha, A., & Sabharwal, N. S. (2015). Issues of under-representation: Mapping women in indian politics. Journal of South Asian Studies, 3(1), 93–102.

Low, S., & Smith, N. (Eds.). (2013). The politics of public space. Routledge.

McMillan, A. (2012). The election commission of India and the regulation and administration of electoral politics. Election Law Journal, 11(2), 187–201.

Michelutti, L. (2020). The vernacularisation of democracy: Politics, caste and religion in India. Taylor & Francis.

Michelutti, L., & Heath, O. (2013). The politics of entitlement: Affirmative action and strategic voting in Uttar Pradesh, India. Focaal, 2013(65), 56–67.

Mitra, A., & Ray, D. (2019). Hindu-Muslim violence in India: A postscript from the twenty-first century. In Advances in the economics of religion (pp. 229–248). Palgrave Macmillan.

Nielsen, K. B. (2011). In search of development: Muslims and electoral politics in an Indian State. In Forum for development studies (Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 345–370). Routledge.

Palshikar, S., Kumar, S., & Lodha, S. (Eds.). (2017). Electoral politics in India: The resurgence of the Bharatiya Janata party. Taylor & Francis.

Pye, M. W., & Pye, L. W. (2009). Asian power and politics: The cultural dimensions of authority. Harvard University Press.

Rajadesingan, A., Panda, A., & Pal, J. (2020). Leader or party? Personalization in twitter political campaigns during the 2019 Indian Elections. In International conference on social media and society, pp. 174–183.

Ranco, D. (2007). The ecological Indian and the politics of representation. Native Americans and the Environment: Perspectives on the Ecological Indian, 1, 32–51.

Rehman, M. (Ed.). (2018). Rise of saffron power: reflections on Indian politics. Taylor & Francis.

Sardesai, R. (2015). The election that changed India. Penguin.

Sharma, A. (2015). A shift from identity politics in the 2014 India election: the BJP towards moderation. ElEctIon, 15

Singh, R. L. (1971). India; a regional geography.

Sinha, A. (2016). Why has development become a political issues in Indian politics. Brown Journal of World Affair, 23, 189.

Swaminathan, S., & Palshikar, S. (Eds.). (2020). Politics and society between elections: Public opinion in India’s States. Taylor & Francis.

Vaishnav, M. (2019). The BJP in power: Indian democracy and religious nationalism. Carnegie endowment for international peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/files/BJP_In_Power_final. June, 18, 2020.

Vertovec, S. (2011). The cultural politics of nation and migration. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 241–256.

Yadav, Y., & Palshikar, S. (2009). Principal state level contests and derivative national choices: Electoral trends in 2004–09. Economic and Political Weekly, 5, 55–62.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the cooperation and advice of my respected two of our best seniors and Dr. Ashis Kumar Parshari, Dr. Rustom Ali, Dr. Mainul SK. Finally, I thank all the members and respondents of the political parties and the Election Commission of India, CSDS, for valuable information. The author also acknowledges the financial assistance provided by the University Grants Commission (UGC) to carry out the current research work.

Funding

No fund was received from any sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The present study ensures objectivity and transparency are followed in this research and acknowledges ethical and professional behavior principles. The current research confirms that: Therefore, for this research, compliance with ethical standards is not applicable.

Human or animal rights

Human Participants or Animals were not engaged or involved in the present research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, F., Khan, N., Ahamed, M.F. et al. Dynamic of electoral behaviour in Uttar Pradesh: a study of lok sabha elections from 2009 to 2019. GeoJournal 88, 1317–1340 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10685-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10685-6