Abstract

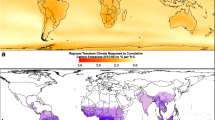

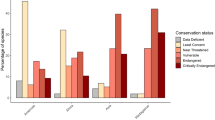

Human-induced climate change poses many potential threats to nonhuman primate species, many of which are already threatened by human activities such as deforestation, hunting, and the exotic pet trade. Here, we assessed the exposure and potential vulnerability of all nonhuman primate species to projected future temperature and precipitation changes. We found that overall, nonhuman primates will experience 10 % more warming than the global mean, with some primate species experiencing >1.5 °C for every °C of global warming. Precipitation changes are likely to be quite varied across primate ranges (from >7.5 % increases per °C of global warming to >7.5 % decreases). We also identified individual endangered species with existing vulnerabilities (owing to their small range areas, specialized diet, or restricted habitat use) that are expected to experience the largest climate changes. Finally, we defined hotspots of primate vulnerability to climate changes as areas with many primate species, high concentrations of endangered species, and large expected climate changes. Although all primate species will experience substantial changes from current climatic conditions, our hotspot analysis suggests that species in Central America, the Amazon, and southeastern Brazil, as well as portions of East and Southeast Asia, may be the most vulnerable to the anticipated impacts of global warming. It is essential that impacts of human-induced climate change be a priority for research and conservation planning in primatology, particularly for species that are already threatened by other human pressures. The vulnerable species and regional hotspots that we identify here represent critical priorities for conservation efforts, as existing challenges are expected to become increasingly compounded by the impacts of global warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barrett, M. A., Brown, J. L., Junge, R. E., & Yoder, A. D. (2013). Climate change, predictive modeling and lemur health: assessing impacts of changing climate on health and conservation in Madagascar. Biological Conservation, 157, 409–422.

Beehner, J. C., Onderdonk, D. A., Alberts, S. C., & Altmann, J. (2006). The ecology of conception and pregnancy failure in wild baboons. Behavioral Ecology, 17, 741–750.

Behie, A. M., Kutz, S., & Pavelka, M. (2014). Cascading effects of climate change: Do hurricane-damaged forests increase risk of exposure to parasites? Biotropica, 46, 25–31.

Chapman, C. A., Lawes, M. J., & Eeley, H. A. C. (2006). What hope for African primate diversity? African Journal of Ecology, 44, 116–133.

Chapman, C. A., Speirs, M. L., Hodder, S. A. M., & Rothman, J. M. (2010). Colobus monkey parasite infections in wet and dry habitats: implications for climate change. African Journal of Ecology, 48, 555–558.

Cheney, D. L., Seyfarth, R. M., Fischer, J., Beehner, J., Bergman, T., Johnson, S. E., Kitchen, D. M., Palombit, R. A., Rendall, D., & Silk, J. B. (2004). Factors affecting reproduction and mortality among baboons in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. International Journal of Primatology, 25, 401–428.

Collins, M., Knutti, R., Arblaster, J., Dufresne, J.-L., Fichefet, T., et al. (2013). Long-term climate change: Projections, commitments and irreversibility. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1–108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). Impact of global warming on the distribution and survival of the gelada baboon: a modelling approach. Global Change Biology, 4, 293–304.

Dunham, A. E., Erhart, E. M., & Wright, P. C. (2010). Global climate cycles and cyclones: consequences for rainfall patterns and lemur reproduction in Southeastern Madagascar. Global Change Biology, 17, 219–227.

ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute). (2012). ArcMap 10.1. ArcGIS 10.1 SP1 for desktop. Redlands: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

Foden, W. B., Butchart, S. H. M., Stuart, S. N., Vié, J.-C., Akçakaya, H. R., et al. (2013). Identifying the world’s most climate change vulnerable species: a systematic trait-based assessment of all birds, amphibians and corals. PloS One, 8, e65427.

González-Zamora, A., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Chaves, O. M., Sánchez-López, S., Aureli, F., & Stoner, K. E. (2011). Influence of climatic variables, forest type, and condition on activity patterns of Geoffroyi’s spider monkeys throughout Mesoamerica. American Journal of Primatology, 73, 1189–1198.

Gould, L., Sussman, R. W., & Sauther, M. L. (1999). Natural disasters and primate populations: the effects of a 2-year drought on a naturally occurring population of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) in Southwestern Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology, 20, 69–84.

Hansen, M. C., Stehman, S. V., & Potapov, P. V. (2010). Quantification of global gross forest cover loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 107, 8650–8655.

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). (2012). IUCN red list of threatened species version 2012.1. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

King, S. J., Arrigo-Nelson, S. J., Pochron, S. T., Semprebon, G. M., Godfrey, L. R., Wright, P. C., & Jernvall, J. (2005). Dental senescence in a long-lived primate links infant survival to rainfall. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 102, 16579–16583.

Korstjens, A. H., Lehmann, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2010). Resting time as an ecological constraint on primate biogeography. Animal Behaviour, 79, 361–374.

Kosheleff, V. P., & Anderson, C. N. (2009). Temperature’s influence on the activity budget, terrestriality, and sun exposure of chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest, Uganda. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 139, 172–181.

Lehmann, J., Korstjens, A. H., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2010). Apes in a changing world: the effects of global warming on the behaviour and distribution of African apes. Journal of Biogeography, 37, 2217–2231.

Markovic, M., de Elía, R., Frigon, A., & Matthews, H. D. (2013). A transition from CMIP3 to CMIP5 for climate information providers: the case of surface temperature over Eastern North America. Climatic Change, 120, 197–210.

Meehl, G. A., Covey, C., Delworth, T., Latif, M., McAvaney, B., Mitchell, J. F. B., Stouffer, R. J., & Taylor, K. E. (2007). The WCRP CMIP3 multi-model dataset: a new era in climate change research. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 88, 1383–1394.

Meyer, A. L. S., Pie, M. R., & Passos, F. C. (2014). Assessing the exposure of lion tamarins (Leontopithecus spp.) to future climate change. American Journal of Primatology, 76, 551–562.

Milton, K., & Giacalone, J. (2014). Differential effects of unusual climatic stress on capuchin (Cebus capucinus) and howler monkey (Alouatta palliata) populations on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. American Journal of Primatology, 76, 249–261.

Mitchell, D., Fuller, A., & Maloney, S. K. (2009). Homeothermy and primate bipedalism: is water shortage or solar radiation the main threat to baboon (Papio hamadryas) homeothermy? Journal of Human Evolution, 56, 439–446.

Pacifici, M., Foden, W. B., Visconti, P., Watson, J. E. M., Butchart, S. H. M., et al. (2015). Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 5, 215–225.

Pavé, R., Kowalewski, M. M., Garber, P. A., Zunino, G. E., Fernandez, V. A., & Peker, S. M. (2012). Infant mortality in black-and-gold howlers (Alouatta caraya) living in a flooded forest in Northeastern Argentina. International Journal of Primatology, 33, 937–957.

Pavelka, M. S. M., Brusselers, O. T., Nowak, D., & Behie, A. M. (2003). Population reduction and social disorganization in Alouatta pigra following a hurricane. International Journal of Primatology, 24, 1037–1055.

Pavelka, M. S. M., McGoogan, K., & Steffens, T. S. (2007). Population size and characteristics of Alouatta pigra before and after a major hurricane. International Journal of Primatology, 28, 919–929.

Raghunathan, N., François, L., Huynen, M.-C., Oliveira, L. C., & Hambuckers, A. (2015). Modelling the distribution of key tree species used by lion tamarins in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest under a scenario of future climate change. Regional Environmental Change, 14, 683–693.

Schloss, C. A., Nuñez, T. A., & Lawler, L. (2012). Dispersal will limit ability of mammals to track climate change in the Western Hemisphere. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 109, 8606–8611.

Scholze, M., Knorr, W., Arnell, N. W., & Prentice, I. C. (2006). A climate-change risk analysis for world ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 103, 13116–13120.

Seto, K. C., Güneralp, B., & Hutyra, L. R. (2012). Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 109, 16083–16088.

Solomon, S., Plattner, G.-K., Knutti, R., & Friedlingstein, P. (2009). Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 106, 1704–1709.

Solomon, S., Battisti, D., Doney, S., Hayhoe, K., Held, I. M., et al. (2011). Physical climate change in the 21st century. In Climate stabilization targets: emissions, concentrations and impacts over decades to millennia (pp. 105–158). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Strassburg, B. B. N., Rodrigues, A. S. L., Gusti, M., Balmford, A., Fritz, S., et al. (2012). Impacts of incentives to reduce emissions from deforestation on global species extinctions. Nature Climate Change, 2, 350–355.

Tebaldi, C., & Arblaster, J. M. (2014). Pattern scaling: its strengths and limitations, and an update on the latest model simulations. Climatic Change, 122, 459–471.

Waite, T. A., Chhangani, A. K., Campbell, L. G., Rajpurohit, L. S., & Mohnot, S. A. (2007). Sanctuary in the city: urban monkeys buffered against catastrophic die-off during ENSO-related drought. EcoHealth, 4, 278–286.

Walther, G.-R., Post, E., Convey, P., Menzel, A., Parmesan, C., et al. (2002). Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature, 416, 389–395.

Wiederholt, R., & Post, E. (2010). Tropical warming and the dynamics of endangered primates. Biology Letters, 6, 257–260.

Wiederholt, R., & Post, E. (2011). Birth seasonality and offspring production in threatened Neotropical primates related to climate. Global Change Biology, 17, 3035–3045.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Freeman, D. Naud, and the members of the Concordia Climate Science, Impacts and Mitigation Studies (C2SIMS) Lab for their contributions and feedback during the research process, as well as D. Seto and M. Burelli for G.I.S. technical support. We thank J. Setchell, A. Korstjens, and one anonymous reviewer for their helpful suggestions and critiques of earlier versions of this manuscript. We would also like to express our appreciation for access to the All the World’s Primates database and to M. Myers for answering our questions about the data therein. T. L. Graham and H. D. Matthews acknowledge funding from the Concordia Institute for Water, Energy and Sustainable Systems (CIWESS) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). S. E. Turner thanks Le Fonds de recherche du Québec–Nature et technologies (FRQNT) for a postdoctoral fellowship that helped support this research, S. Reader for his support, and L. Gould for helpful conversations during early phases of this project. H. D. Matthews and S. E. Turner thank M. Amichai for childcare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Three supplementary figures (Figs. S1, S2, and S3) and a list of primate species ordered by category of projected climate change severity, including projected changes in annual mean temperature and precipitation for each species’ range, as well as range area, and food and habitat use for each species (Table SI) are available online.

Fig. S1

Average temperature and precipitation change expected for each primate species. The dotted lines outline the boundaries of the climate change severity categories shown in Table III. Species are color-coded by genus, as given by the color bar. (GIF 159 kb)

Fig. S2

Average (circles) and standard deviation (lines) of temperature and precipitation change for each primate genus. The dotted lines outline the boundaries of the climate change severity categories shown in Table III. Genera are color coded according to the color bar, and those genera expected to experience the largest climate changes (category 4 or higher) are also labeled on the plot. (GIF 187 kb)

Fig. S3

Hotspots of primate vulnerability to global warming, calculated as in Fig. 6, but using the number of genera rather than the number of species per km2. Hotspot scores are calculated (per km2) as the product of normalized measures of genera richness, average extinction risk, and climate change severity, and are classified here by quantile. Darkest pixels (upper quantiles) indicate locations of high genera richness, where primates are currently threatened by human pressures, and where large changes in temperature and/or precipitation are expected to occur. (PDF 263 kb)

Table SI

(DOCX 155 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Graham, T.L., Matthews, H.D. & Turner, S.E. A Global-Scale Evaluation of Primate Exposure and Vulnerability to Climate Change. Int J Primatol 37, 158–174 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-016-9890-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-016-9890-4