Abstract

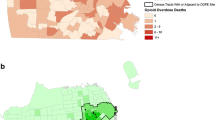

Recently implemented New York State policy allows police and fire to administer intranasal naloxone when responding to opioid overdoses. This work describes the geographic distribution of naloxone administration (NlxnA) by police and fire when responding to opioid overdoses in Erie County, NY, an area of approximately 920,000 people including the City of Buffalo. Data are from opioid overdose reports (N = 800) filed with the Erie County Department of Health (July 2014–June 2016) by police/fire and include the overdose ZIP code, reported drug(s) used, and NlxnA. ZIP code data were geocoded and mapped to examine spatial patterns of NlxnA. The highest NlxnA rates (range: 0.01–84.3 per 10,000 population) were concentrated within the city and first-ring suburbs. Within 3 min 27.3% responded to NlxnA and 81.6% survived the overdose. The average individual was male (70.3%) and 31.4 years old (SD = 10.3). Further work is needed to better understand NlxnA and overdose, including exploring how the neighborhood environment creates a context for drug use, and how this context influences naloxone use and overdose experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rudd, R. A., et al. (2016) Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. In Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pollini, R. A., et al. (2006). Response to overdose among injection drug users. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(3), 261–264.

Boyer, E. W. (2012). Management of opioid analgesic overdose. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(2), 146–155.

Tobin, K. E., et al. (2009). Evaluation of the Staying Alive programme: Training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. International Journal on Drug Policy, 20(2), 131–136.

Davis, C. S., & Carr, D. (2015). Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 112–120.

Tracy, M., et al. (2005). Circumstances of witnessed drug overdose in New York City: implications for intervention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 79(2), 181–190.

Sporer, K. A. (2003). Strategies for preventing heroin overdose. British Medical Journal, 326(7386), 442–444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7386.442.

Strang, J., Darke, S., Hall, W., Farrell, M., & Ali, R. (1996). Heroin overdose: The case for take-home naloxone. British Medical Journal, 312(7044), 1435–1436.

Tobin, K. E., Davey, M. A., & Latkin, C. A. (2005). Calling emergency medical services during drug overdose: An examination of individual, social and setting correlates. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 100(3), 397–404.

Banta-Green, C. J., et al. (2013). Police officers’ and paramedics’ experiences with overdose and their knowledge and opinions of Washington State’s drug overdose–naloxone–Good Samaritan law. Journal of Urban Health, 90(6), 1102–1111.

Davis, C. S., et al. (2015). Engaging law enforcement in overdose reversal initiatives: authorization and liability for naloxone administration. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 1530–1537.

Davis, C. S., et al. (2014). Expanded access to naloxone among firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians in Massachusetts. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), e7-9.

Fisher, R., O'Donnell, D., Ray, B., & Rusyniak, D. (2016). Police officers can safely and effectively administer intranasal naloxone. Prehospital Emergency Care, 20(6), 675–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2016.1182605.

Cicero, T. J., et al. (2014). The changing face of heroin use in the United States: A retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(7), 821–826.

Harris, P. A., et al. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381.

Kim, D., Irwin, K. S., & Khoshnood, K. (2009). Expanded access to naloxone: Options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 99(3), 402–407.

Dasgupta, N., et al. (2014). Observed transition from opioid analgesic deaths toward heroin. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 238–241.

Mars, S. G., et al. (2014). “Every ‘Never’ I Ever Said Came True”: Transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting. International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(2), 257–266.

Carlson, R. G., et al. (2016). Predictors of transition to heroin use among initially non-opioid dependent illicit pharmaceutical opioid users: A natural history study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 127–134.

New York State Department of Health. (2013) I-STOP/PMP—Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing—Prescription Monitoring Program. Retrieved Feburary 10, 2016, from https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/prescription_monitoring/.

Knowlton, A., et al. (2013). EMS runs for suspected opioid overdose: Implications for surveillance and prevention. Prehospital Emergency Care: Official Journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors, 17(3), 317–329.

Krieger, N., et al. (2002). Zip code caveat: Bias due to spatiotemoral mismatches between zip codes and US census-defined geographic areas—The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. American Journal of Public Health, 92(7), 1100–1102.

Grubesic, T. H., & Matisziw, T. C. (2006). On the use of ZIP codes and ZIP code tabulation areas (ZCTAs) for the spatial analysis of epidemiological data. International Journal of Health Geographics, 5, 58.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heavey, S.C., Delmerico, A.M., Burstein, G. et al. Descriptive Epidemiology for Community-wide Naloxone Administration by Police Officers and Firefighters Responding to Opioid Overdose. J Community Health 43, 304–311 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0422-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0422-8