Abstract

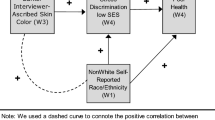

This study reveals the association of skin color with health disparities in Puerto Rico, a US territory that is home to the second largest Latino population in the US. Aware of the inadequacy of standard OMB ethno-racial categories in capturing racial differences among Latinos, we incorporated skin color scales into the Puerto Rico BRFSS. We apply both logistic regressions and propensity score matching techniques. We found that colorism plays a significant role in health outcomes of dark-skinned Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and that skin color is a better health predictor than the OMB ethno-racial categories. Our results indicate that Puerto Ricans of the lightest skin tone have better general health than Puerto Ricans who self-described as being of the darkest skin tones. Findings underscore the importance of considering how racial discrimination manifested through colorism affects the health of Latino populations in the US and its territories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Table 1 below we illustrate how most respondents located themselves in the middle of the skin color spectrum.

References

Araújo BY, Borrell LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28(2):245–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986305285825.

Borrell LN. Race, ethnicity, and self-reported hypertension: analysis of data from the national health interview survey, 1997–2005. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):313–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.123364.

Cuevas AG, Dawson BA, Williams DR. Race and skin color in Latino health: an analytic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(12):2131–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303452.

Gravlee CC, Dressler WW. Skin pigmentation, self-perceived color, and arterial blood pressure in Puerto Rico. Am J Hum Biol Off J Hum Biol Assoc. 2005;17(2):195–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20111.

Landale NS, Oropesa RS. What does skin color have to do with infant health? An analysis of low birth weight among mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(2):379–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.029.

Sanchez GL, Ybarra VD. Lessons from Political Science: Health status and improving how we study race. In: Valdez RB, Kahn J, Graves JL, Kaufman JS, Garcia JA, Lee SJC, Miller M, editors. Mapping “Race”: critical approaches to health disparities research. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2013. p. 104–16.

Telzer EH, Vazquez Garcia HA. Skin color and self-perceptions of immigrant and U.S.-born Latinas: the moderating role of racial socialization and ethnic identity. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2009;31(3):357–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986309336913.

Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, Kinlock BL. The enhanced self-reported health outcome observed in Hispanics/Latinos who are socially-assigned as white is dependent on nativity. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(6):1803–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0134-4.

Wassink J, Perreira KM, Harris KM. Beyond race/ethnicity: skin color and cardiometabolic health among blacks and Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(5):1018–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0495-y.

Araújo Dawson B. Discrimination, stress, and acculturation among Dominican immigrant women. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2009;31(1):96–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986308327502.

Ayers SL, Kulis S, Marsiglia FF. The impact of ethnoracial appearance on substance use in Mexican heritage adolescents in the Southwest United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2013;35(2):227–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986312467940.

Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegria M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(4):421–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20221.

Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1524–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010.

Codina GE, Montalvo FF. Chicano phenotype and depression. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1994;16(3):296–306.

Cook B, Alegría M, Lin JY, Guo J. Pathways and correlates connecting Latinos’ mental health with exposure to the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2247–54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.137091.

Perreira KM, Telles E. The color of health: skin color, ethnoracial classification, and discrimination in the health of Latin Americans. Soc Sci Med. 2014;116:241–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.054.

Telles E. Pigmentocracies: ethnicity, race, and color in Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 2014.

Colón-Ramos U, Rodríguez-Ayuso I, Gebrekristos HT, Roess A, Pérez CM, Simonsen L. Transnational mortality comparisons between archipelago and mainland Puerto Ricans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(5):1009–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0448-5.

Mattei J, Tamez M, Ríos-Bedoya CF, Xiao RS, Tucker KL, Rodríguez-Orengo JF. Health conditions and lifestyle risk factors of adults living in Puerto Rico: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):491. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5359-z.

Daviglus ML, Pirzada A, Talavera GA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Hispanic/Latino population: lessons from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57(3):230–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2014.07.006.

Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, LaVange L. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(17):1775–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.14517.

Tucker KL, Mattei J, Noel SE, Collado BM, Mendez J, Nelson J, Falcon LM. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):107–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-107.

Borrell LN, Crespo CJ, Garcia-Palmieri MR. Skin color and mortality risk among men: the Puerto Rico Heart Health Program. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(5):335–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.11.002.

Godreau I, Morales M, Franco Ortiz M, Suarez Rivera Á. Color y desigualdad: Estudio exploratorio sobre el uso de escalas de color de piel para conocer la vulnerabilidad y percepción del discrimen entre Latinos y Latinas. Revista Umbral. 2018;14:33–80. http://umbral.uprrp.edu/ndeg-14-conocimiento-contribuciones-consciencia-afrodescendientehttp://umbral.uprrp.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Nu%CC%81mero-14.pdf#page=33.

Puerto Rico, Departamento de Salud: Puerto Rico chronic disease action plan 2014–2020. San Juan: Puerto Rico Departmento de Salud; 2013. https://www.iccp-portal.org/sites/default/files/plans/Puerto%20Rico%20Chronic%20Disease%20Action%20Plan%20English.pdf.

CDC (2016). BRFSS combined landline and cell phone weighted response rates by state, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/2016_ResponseRates_Table.pdf.

Benjamins MR, Hirschman J, Hirschtick J, Whitman S. Exploring differences in self-rated health among Blacks, Whites, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans. Ethn Health. 2012;17(5):463–76.

Hajat A, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Siddiqi A, Thomas JC. Long-term effects of wealth on mortality and self-rated health status. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(2):192–200.

Hurtado D, Kawachi I, Sudarsky J. Social capital and self-rated health in Colombia: the good, the bad and the ugly. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(4):584–90.

Burström B, Fredlund P. Self rated health: is it as good a predictor of subsequent mortality among adults in lower as well as in higher social classes? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(11):836–40.

Chandola T, Jenkinson C. Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups. Ethn Health. 2000;5(2):151–9.

Telles E, Flores RD, Urrea-Giraldo F. Pigmentocracies: educational inequality, skin color and census ethnoracial identification in eight Latin American countries. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2015;40:39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2015.02.002.

Rodriguez CE. Changing race: Latinos, the census, and the history of ethnicity in the United States. New York: NYU Press; 2000.

Vargas-Ramos C. Black, Trigueño, White … ? Shifting racial identification among Puerto Ricans. Du Bois Rev. 2005;2(2):267.

Duany J. Neither white nor black: the representation of racial identity among Puerto Ricans on the Island and in the US Mainland. In: Oboler S, Anani D, editors. Neither enemies nor friends: Latinos, Blacks, Afro-Latinos. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. p. 173–88.

Godreau I, Lloréns H, Vargas-Ramos C. Colonial incongruence at work: employing US census racial categories in Puerto Rico. Anthropol News. 2010;51(5):11–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51511.x.

Lloréns H, Garcia-Quijano C, Godreau I. Racismo en Puerto Rico: surveying perceptions of racism. Cent J. 2017;28(3):10–38.

Travassos C, Laguardia J, Marques PM, Mota JC, Szwarcwald CL. Comparison between two race/skin color classifications in relation to health-related outcomes in Brazil. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):35.

Hall JC. No longer invisible: understanding the psychosocial impact of skin color stratification in the lives of African American women. Health Soc Work. 2017;42(2):71–8.

Dixon AR, Telles EE. Skin color and colorism: global research, concepts, and measurement. Ann Rev Sociol. 2017;43:405–24.

Monk EP Jr. The cost of color: skin color, discrimination, and health among African-Americans. Am J Sociol. 2015;121(2):396–444. https://doi.org/10.1086/682162.

Prus SG. Comparing social determinants of self-rated health across the United States and Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(1):50–9.

Imbens GW. Nonparametric estimation of average treatment effects under exogeneity: a review. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(1):4–29. https://doi.org/10.3386/t0294.

Moffitt RA. Introduction to the symposium on the econometrics of matching. Rev Econ Stat. 2004;86(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465304323023642.

Frölich M. Propensity score matching without conditional independence assumption—with an application to the gender wage gap in the United Kingdom. Economet J. 2007;10(2):359–407.

Caraballo-Cueto J, Segarra-Alméstica E. Do gender disparities exist despite a negative gender earnings gap? Economía. 2019;19(2):101–25.

Loveman M. The US Census and the contested rules of racial classification in early twentieth-century Puerto Rico. Caribb Stud. 2007;35(2):79–114.

Hoetink H. The two variants in Caribbean race relations. London: Oxford University Press; 1967.

Frank R, Akresh IR, Lu B. Latino immigrants and the US racial order: how and where do they fit in? Am Sociol Rev. 2010;75(3):378–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410372216.

Paradies Y, Jehonathan B, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, Gee G. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9): 1–48.

Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099–106.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8):1152–73.

Hodson G, Esses V. Report: Distancing oneself from negative attributes and the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;38:500–7.

Lindsey A, King E, Cheung H. When do women respond against discrimination? Exploring factors of subtlety, form, and focus. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2015;45(12):649–61.

Taylor DM, Wright SC, Porter LE. Dimensions of perceived discrimination: the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. In: Zanna MP, Olson JM, editors. The psychology of prejudice: the Ontario symposium, vol. 7. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum; 1996. p. 233–255.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research came from the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) at Cayey campus, the UPR Medical Health Science Campus RCMI Program, the Faculty Resource Network and the Princeton University VISAPUR Program. We are grateful with the editor and an anonymous reviewer for their thorough feedback. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caraballo-Cueto, J., Godreau, I.P. Colorism and Health Disparities in Home Countries: The Case of Puerto Rico. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 926–935 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01222-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01222-7