Abstract

Purpose

Workers’ compensation schemes usually recompense workers below their regular wage. This may cause financial stress, which has previously been associated with poorer health and work outcomes after injury. We sought to determine the level of financial stress experienced by injured workers and the influence of post-injury income source on financial stress.

Methods

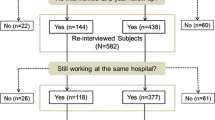

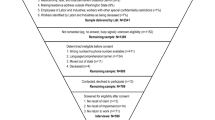

Analysis of a cross-sectional national survey of 4532 adults who had been injured at work and had at least one day of workers’ compensation paid. Financial stress at time of survey was measured on a scale of 1–10 and subsequently dichotomised at the top quartile for further analysis. The effect of current main income source on financial stress, adjusted for demographic and psychosocial confounders, was assessed using logistic regression.

Results

Sixty-nine percent of workers whose main income was social assistance or insurance and 54% whose main income was workers’ compensation were experiencing financial stress. Relative to wages or salaries, workers with a main income from social assistance or insurance (odds ratio: 3.33, 95% CI 2.22–5.00) and workers’ compensation (1.71, 1.31–2.24) had higher odds of financial stress. Workers with a main income of an aged pension or superannuation had lower odds of financial stress (0.52, 0.28–0.97).

Conclusion

Injured workers receiving workers’ compensation or social assistance benefits are vulnerable to increased financial stress. Given the potential negative consequences of financial stress on health, particularly mental health, this study suggests the need for careful consideration of income replacement benefits in the design of workers’ compensation schemes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Safe Work Australia but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Safe Work Australia and the Australian state, territory and Commonwealth workers compensation regulatory authorities.

References

International Labour Office Geneva. Safety in numbers: Pointers for a global safety culture at work. International Labour Office, Geneva; 2003.

Safe Work Australia. The cost of work-related injury and illness for Australian employers, workers and the community 2012–2013. Canberra, Australia; 2015.

Sheehan LR, Gray SE, Lane TJ, Beck D, Collie A. Long-term workers’ compensation claims in Australia. Melbourne: Insurance Work and Health Group, Monash University; 2018.

Lund T, Labriola M, Christensen KB, Bultmann U, Villadsen E. Return to work among sickness-absent Danish employees: prospective results from the Danish Work Environment Cohort Study/National Register on Social Transfer Payments. Int J Rehabil Res. 2006;29(3):229–235.

de Wit M, Wind H, Hulshof CTJ, Frings-Dresen MHW. Person-related factors associated with work participation in employees with health problems: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91(5):497–512.

Finity Consulting. A Best Practice Workers Compensation Scheme. New South Wales: Insurance Council of Australia: Sydney; 2015.

Safe Work Australia. Comparison of workers' compensation arrangements in Australia and New Zealand. Canberra, Australia; 2018.

Social Security Administration. Social Security Programs Throughout the World 2017–2018 [September 5, 2019]. www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/.

Texas Department of Insurance Workers' Compensation Research Group. Comparison of State Workers' Compensation Systems Austin, TX, USA. www.senate.texas.gov/cmtes/78/c780/comprswcompn0325.pdf. Accessed 5 Sept 2019.

Meyer BD, Viscusi WK, Durbin DL. Workers’ compensation and injury duration: evidence from a natural experiment. Am Econ Rev. 1995;85(3):322–340.

Hansen B, Nguyen T, Waddell GR. Benefit generosity and injury duration: quasi-experimental evidence from regression kinks. 2017.

Lane TJ, Gray SE, Sheehan L, Collie A. Increased benefit generosity and the impact on workers' compensation claiming behavior: an interrupted time series study in Victoria, Australia. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(3):e82–e90.

Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–1029.

Beckfield J, Bambra C. Shorter lives in stingier states: social policy shortcomings help explain the US mortality disadvantage. Soc Sci Med. 2016;171:30–38.

Ioannou L, Cameron PA, Gibson SJ, Ponsford J, Jennings PA, Georgiou-Karistianis N et al. Financial and recovery worry one year after traumatic injury: a prognostic, registry-based cohort study. Injury. 2018;49(5):990–1000.

Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):115–119.

Skapinakis P, Weich S, Lewis G, Singleton N, Araya R. Socio-economic position and common mental disorders. Longitudinal study in the general population in the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:109–117.

Franche RL, Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin FC, Bultmann U et al. Course, diagnosis, and treatment of depressive symptomatology in workers following a workplace injury: a prospective cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(8):534–546.

Carnide N, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin FC, Severin CN et al. Course of depressive symptoms following a workplace injury: a 12-month follow-up update. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(2):204–215.

Lane TJ, Collie A, Hassani-Mahmooei B. Work-related injury and illness in Australia, 2004 to 2014. What is the incidence of work-related conditions and their impact on time lost from work by state and territory, age, gender and injury type? Melbourne, Australia: Institute for Safety Compensation and Recovery Research, June 2016. Report No.: Contract No.: 118-0616-R02; 2016.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 6202.0: Labour Force Australia. Canberra, Australia; 2019.

Social Research Centre. Return to Work Survey, 2017/18: Headline Measures Report. Melbourne: Safe Work Australia; 2018.

Prawitz A, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J Financ Counsel Plan. 2006;17(1):34–50.

Butterworth P, Leach LS, Strazdins L, Olesen SC, Rodgers B, Broom DH. The psychosocial quality of work determines whether employment has benefits for mental health: results from a longitudinal national household panel survey. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(11):806–812.

Australian Government Department of Human Services. Income test for FTB Part A. https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/family-tax-benefit/how-much-you-can-get/income-test-ftb-part. Accessed 31 Jan 2020.

Franche RL, Severin CN, Lee H, Hogg-Johnson S, Hepburn CG, Vidmar M et al. Perceived justice of compensation process for return-to-work: development and validation of a scale. Psychol Injury Law. 2009;2(3):225–237.

Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: an introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 15.1. College Station: StataCorp LLC; 2017.

RSudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R; 2019.

Wickham H. tidyverse: easily install and load the "Tidyverse"; 2017.

Lüdecke DMD, Waggoner P, Ben-Shachar MS. see: Visualisation Toolbox for "easystats" and Extra Geoms, Themes, and Color Palettes for 'ggplot2"; 2019.

Cylus J, Glymour MM, Avendano M. Health effects of unemployment benefit program generosity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):317–323.

O'Campo P, Molnar A, Ng E, Renahy E, Mitchell C, Shankardass K, et al. Social welfare matters: a realist review of when, how, and why unemployment insurance impacts poverty and health. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:88–94.

Catalano R, Goldman-Mellor S, Saxton K, Margerison-Zilko C, Subbaraman M, LeWinn K, et al. The health effects of economic decline. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:431–450.

Dean AM, Matthewson M, Buultjens M, Murphy G. Scoping review of claimants' experiences within Australian workers' compensation systems. Australian health review: a publication of the Australian Hospital Association; 2018.

Australian Government Department of Human Services. Newstart Allowance - How much you can get. https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/newstart-allowance/how-much-you-can-get. Accessed 26 Jun 2019.

Australian Government Department of Human Services. Age Pension - How much you can get. https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/age-pension/how-much-you-can-get. Accessed 12 Sept 2019.

Laß I, Wooden M. Trends in the prevalence of non-standard employment in Australia. J Ind Relat. 2019;62(1):3–32.

Australian Government. Social Security Guide: 3.2.8.10 Mutual Obligation Requirements for NSA/YA Job Seekers Overview. Canberra, Australia; 2019.

Ryan C. Responses to financial stress at life transition points. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs; 2012.

Collie A, Lane TJ, Hassani-Mahmooei B, Thompson J, McLeod C. Does time off work after injury vary by jurisdiction? A comparative study of eight Australian workers’ compensation systems. BMJ Open. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010910

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Australian Research Council (DP190102473). This publication uses data supplied by Safe Work Australia that was compiled in collaboration with state, territory and Commonwealth workers’ compensation regulators. The views expressed are the authors and are not necessarily the views of Safe Work Australia or the state, territory and Commonwealth workers’ compensation regulators. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Ms Dianne Beck for assistance with data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Luke R. Sheehan, Tyler J. Lane and Alex Collie declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee approval reference number CF14/2995-2014001663) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sheehan, L.R., Lane, T.J. & Collie, A. The Impact of Income Sources on Financial Stress in Workers’ Compensation Claimants. J Occup Rehabil 30, 679–688 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09883-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09883-1