Abstract

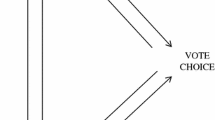

A comprehensive literature relates voters’ electoral decisions to their perceptions of candidates’ personalities. Yet the mechanisms through which voters are attracted to certain candidates and not to others remain largely unresolved. To answer this question, this article integrates two recent interdisciplinary insights. First, leader and candidate preferences are found to be strongly dependent on levels of contextual conflict. Second, individual differences in political ideology are shown to be rooted in psychological orientations leading conservatives and liberals to perceive society in fundamentally different ways: Conservatives tend to perceive the social world as dangerous and threatening, whereas liberals to a larger degree see society as a safe place characterized by cooperation. Based on this, it is predicted that conservatives and liberals will also prefer different candidate personalities. Specifically, conservatives are predicted to value candidate power and “strong leadership” more than liberals, whereas liberals are predicted to value candidate warmth more than conservatives. The prediction is supported observationally using the 1984–2008 American National Election Studies and experimentally in two original experiments conducted in the United States and Denmark. Consequences and scope conditions for trait-based voting are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Whereas the studies cited here all stress how conflict contexts cause homogenous changes in leader preferences across the electorate, recent work on “audience costs” suggests that liberal leaders—because they need to cater to liberal audiences who are more conflict averse and concerned about the use of force—will potentially pay a larger price for conflicts than will conservative leaders (Kertzer and Brutger 2016).

Related to the literature cited in this paragraph scholars argue that ideology is composed of (at least) two sub-components of economic and social ideology (or economic and social conservatism) (for two recent accounts see for instance Feldman and Johnston 2014, and Carmines and D’Amico 2015). Here I follow the one dimensional understanding of political ideology employed by Hibbing et al. (2013).

Moreover, the experimental studies constitute a direct test of whether subjects are attracted differently to a candidate described as powerful or warm depending on their ideological predispositions. Importantly, in this test the candidate’s party affiliation remains unknown to subjects. This eliminates the effects of partisanship on overall candidate evaluation and permits the key test of my prediction: Whether mere personality descriptions of a fictitious candidate as either powerful or warm evoke different reactions among conservatives and liberals.

Barker et al. (2006) build their hypotheses on different value priorities among Democrats and Republicans, respectively. Consequently, their study does not distinguish between whether the heterogeneous candidate personality preferences are driven by ideological predispositions or by processes of partisanship and stereotypes.

The ANES cumulative data file is used for all reported analyses. The 1980 election is not included in the analyses since it did not contain warmth-related trait ratings, and prior to 1980 the ANES did not include any trait rating measures.

The ANES furthermore includes ratings of candidate decency (included 1984–1988), and inspiration (included 1984–1996). Because the purpose of Study 1 is to investigate interactive relationships between trait ratings of warmth and strong leadership, respectively, with respondents’ ideology across elections, ratings of decency and inspiration are left out of the analyses to avoid restricting the analyses to a subset of the available election years.

Following Bartels (2002) among others, I exclude respondents who report voting for another candidate than the Republican or the Democrat in the vote-choice analyses. Moreover, only Democratic and Republican candidates are included in the analyses since the ANES does not include trait ratings of other candidates (e.g. Ross Perot in 1992).

Candidates representing the Republican and Democratic parties are coded “0” and “1”, respectively. Respondents’ party identification is measured using the standard ANES seven category variable (variable “VCF0301” in the cumulative ANES data-file) for party identification, which is recoded to a 0–1 scale with “0” representing “Strong Democrats” and “1” representing “Strong Republicans”. As for ideology, the main effect of party affiliation is not estimated as it is respondent invariant and, thus, controlled for through the respondent fixed effects procedure.

Replication data and command files for both Study 1 and Study 2 (the US and the Danish versions) are available at Dataverse Network (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/): doi:10.7910/DVN/KJOH74.

Interestingly, trait impressions of moral also interact positively with respondent ideology for predictions of feelings and vote choice. That is, the more conservative the respondent the larger the weight assigned to ratings of candidates’ moral (for specific tests see Supplementary Material S.4). Different explanations for this finding could be given. In line with the perspective promoted in this article, conservatives might find it more important for their leaders to be morally right based in psychological needs (for order; cf. Jost et al. 2009). Another explanation would build on trait ownerships (cf. Hayes (2005) and stress that the political right (conservatives and Republicans alike) hold trait ownership of moral. For this article, the main conclusion remains that interactions between strong leadership and warmth, respectively, with ideology still hold under this alternative specification, and—as a consequence—it is left for future work to explore the interaction between ratings of candidate moral and respondent ideology further.

Specifically, difference score models control for trait ratings of competence and moral, respondents’ gender, age, party identification, income, race and religiosity (for detailed coding procedures see Supplementary Material S.1).

Besides, Denmark and the United States also differ with respect to more general culture and institutional set-up of potential relevance to political preferences and behavior. The United States embodies federalism, presidentialism, first-past-the-post elections, and a two-party system. Denmark embodies corporatism, parlamentarism, proportional elections, and a multi-party system. These differences also extend into broader culture with the United States being markedly more individualistic and Denmark more collectivistic (Nelson and Shavitt 2002).

The construct validity of these personality descriptions were tested in relation to the applied personality traits used in Study 1. With respect to warmth, the two candidate personality descriptions were rated on “friendliness,” “agreeableness,” and “if the candidate cares about you”—traits linked closely to the warmth dimension and with the latter trait also included in the ANES data—and these ratings correlate positively and significantly: Danish sample: ragreeableness,friendliness = 0.67, p < 0.001; ragreeableness,care = 0.60, p < 0.001; rcare,friendliness = 0.63, p < 0.001. US sample: ragreeableness,friendliness = 0.72, p < 0.001; ragreeableness,care = 0.64, p < 0.001; rcare,friendliness = 0.73, p < 0.001. With respect to power, the two candidate personality descriptions were rated on “dominance,” “competitiveness,” and “strong leadership”—traits linked closely to the power dimension and with the latter trait also included in the ANES data—and these ratings correlate positively and significantly: Danish sample: rdominance,competitiveness = 0.49, p < 0.001; rdominance,strong leadership = 0.23, p < 0.001; rstrong leadership,competitiveness = 0.15, p = 0.016; US sample: rdominance,competitiveness = 0.62, p < 0.001; rdominance,strong leadership = 0.30, p < 0.001; rstrong leadership,competitiveness = 0.41, p < 0.001.

This study is the first to experimentally investigate ideological differences in preferences for candidate power and warmth for which reason several related aspects of power and warmth were simultaneously manipulated. Future studies might potentially look into whether different sub-aspects or sub-indicators of power and warmth constitute the primary drivers of the results.

Party affiliation was measured using the standard ANES seven category measure, which was subsequently recoded to a 0–1 scale with “0” and “1” representing “Strong Democrats” and “Strong Republicans”, respectively. Moreover, due to inclusion of a “don’t know” option for the feeling thermometer rating and not for “likelihood to vote for Thomas Johnson”, the feeling thermometer analysis is based on 340 subjects, while the analysis of “likelihood voting for” involves all 408 subjects.

In their study Duckitt and Sibley (2010) show that political ideology stems from two different paths linking conservatism to two different types of fundamental world views. One world view is characterized by perceiving the social world as dangerous and threatening and relates to conservatism through authoritarianism. The other path relates conservatism to a fundamental perception of society as a competitive jungle with the concept of social dominance orientation (SDO) constituting the intermediate link between world view and conservatism. Since only authoritarianism was included in the American version of Study 2, only authoritarianism can be investigated in the current analyses. However, future research should try to link preferences for candidate personalities to SDO as well as to direct measures of the two different world views.

References

Alford, J., Funk, C., & Hibbing, J. (2005). Are political orientations genetically transmitted? American Political Science Review, 99(2), 153–167.

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc.

Barker, D. C., Lawrence, A. B., & Tavits, M. (2006). Partisanship and the dynamics of “candidate centered politics” in American presidential nominations. Electoral Studies, 25(3), 599–610.

Bartels, L. (2002). The impact of candidate traits in American presidential elections. In A. King (Ed.), Leaders’ personalities and the outcomes of democratic elections (pp. 44–69). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bishin, B., Stevens, D., & Wilson, C. (2006). Character counts? Honesty and fairness in election 2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(2), 235–248.

Bøggild, T., & Laustsen, L. (2016). An intra-group perspective on leader preferences: Different risks of exploitation shape preferences for leader facial dominance. The Leadership Quarterly. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.09.003.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, D. (1960). The American voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carmines, E., & D’Amico, N. (2015). The new look in political ideology research. Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 205–216.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret life of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807–840.

Clarke, H., Sanders, D., Stewart, M., & Whiteley, P. (2004). Political choice in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78, 1861–1894.

Eriksson, K., & Funcke, A. (2013). A below-average effect with respect to American political stereotypes on warmth and competence. Political Psychology, 36(3), 341–350.

Feldman, S. (2013). Political ideology. In H. Leonie, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 591–626). New York: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, S., & Johnston, C. (2014). Understanding the determinants of political ideology: Implications of structural complexity. Political Psychology, 35(3), 337–358.

Feldman, S., & Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18(4), 741–770.

Fiske, S., Cuddy, A., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83.

Funk, C. (1996). The impact of scandal on candidate evaluations: An experimental test of the role of candidate traits. Political Behavior, 18, 1–24.

Funk, C. (1997). Implications of political expertise in candidate trait evaluation. Political Research Quarterly, 50(3), 675–697.

Funk, C. (1999). Bringing the candidate into models of candidate evaluation. Journal of Politics, 61, 700–720.

Gass, N. (2015, October 14). Trump goes on the attack against Bernie. Politico. Retrieved October 17, 2016, from http://www.politico.com/story/2015/10/donald-trump-attack-bernie-sanders-214792.

Goren, P. (2002). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 627–641.

Goren, P. (2007). Character weakness, partisan bias, and presidential evaluation: Modifications and extensions. Political Behavior, 29(3), 305–325.

Hanmer, M., & Kalkan, K. (2013). Behind the curve: Clarifying the best approach to calculating predicted probabilities and marginal effects from limited dependent variable models. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 263–277.

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate quality through a partisan lens: A theory of trait ownership. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 908–923.

Hayes, D. (2009). Has television personalized voting behavior? Political Behavior, 31, 231–260.

Hayes, D. (2010). Trait voting in U.S. senate elections. American Politics Research, 38(6), 1102–1129.

Hibbing, J., Smith, K., & Alford, J. (2013). Predisposed. New York: Routledge.

Hibbing, J., Smith, K., & Alford, J. (2014). Differences in negativity bias underlie variations in political ideology. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 37(3), 297–307.

Hirsch, J., DeYoung, C., Xiaowen, X., & Peterson, J. (2010). Compassionate liberals and polite conservatives: Associations of agreeableness with political ideology and moral values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(5), 655–664.

Jost, J., Federico, C., & Napier, J. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 307–333.

Kalmoe, N. (2013). From fistfights to firefights: Trait aggression and support for state violence. Political Behavior, 35, 311–330.

Kertzer, J., & Brutger, R. (2016). Decomposing audience costs: Bringing the audience back into audience cost theory. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 234–249.

Kilburn, H. (2005). Does the candidate really matter? American Politics Research, 33(3), 335–356.

Kinder, D. (1986). Presidential character revisited. In R. Lau & D. Sears (Eds.), Political cognition (pp. 233–255). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kinder, D., Peters, M., Abelson, R., & Fiske, S. (1980). Presidential prototypes. Political Behavior, 2, 315–337.

Laustsen, L., & Petersen, M. (2015). Does a competent leader make a good friend? Conflict, ideology and the psychologies of friendship and followership. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36, 286–293.

Laustsen, L., & Petersen, M. (2016). Winning faces vary by ideology: How nonverbal source cues influence election and communication success in politics. Political Communication, 33(2), 188–211.

Laustsen, L. & Petersen, M. B. (Forthcoming). Perceived conflict and leader dominance: Individual and contextual factors behind preferences for dominant leaders. Political Psychology.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Little, A., Burriss, R., Jones, B., & Craig Roberts, S. (2007). Facial appearance affects voting decisions. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 18–27.

MacWilliams, M. (2016, January 17). The one weird trait that predicts whether you’re a Trump supporter. Politico. Retrieved October 17, 2016, from http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/01/donald-trump-2016-authoritarian-213533.

Markus, G. (1982). Political attitudes during an election year: A report on the 1980 NES panel study. American Political Science Review, 76(3), 538–560.

Merolla, J., & Zechmeister, E. (2009a). Terrorist threat, leadership, and the vote: Evidence from three experiments. Political Behavior, 31, 575–601.

Merolla, J., & Zechmeister, E. (2009b). Democracy at risk: How terrorist threats affect the public. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Miller, A., & Miller, W. (1976). Ideology in the 1972 election: Myth or reality-a rejoinder. American Political Science Review, 70(3), 832–849.

Nelson, M., & Shavitt, S. (2002). Horizontal and vertical individualism and achievement values: A multimethod examination of Denmark and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 439–458.

Oosterhof, N., & Todorov, A. (2008). The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(32), 11087–11092.

Oxley, D., Smith, K., Alford, J., Hibbing, M., Miller, J., Scalora, M., et al. (2008). Political attitudes vary with physiological traits. Science, 321, 1667–1670.

Peffley, M., Hurwitz, J., & Sniderman, P. (1997). Racial stereotypes and whites’ political views of blacks in the context of welfare and crime. American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 30–60.

Petersen, M., & Aarøe, L. (2013). Politics in the mind’s eye: Imagination as a link between social and political cognition. American Political Science Review, 107(2), 275–293.

Popkin, S. (1994). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion effects in presidential campaigns (2nd ed.). Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Quindlen, A. (2000, August 14). It’s the cult of personality. Newsweek. Retrieved March 9, 2016, from http://www.newsweek.com/its-cult-personality-159127.

Rule, N. O., Ambady, N., Adams, R. B., Jr., Ozono, H., Nakashima, S., Yoshikawa, S., et al. (2010). Polling the face: Prediction and consensus across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 1–15.

Spisak, B., Homan, A., Grabo, A., & van Vugt, M. (2012). Facing the situation: Testing a biosocial contingency model of leadership in intergroup relations using masculine and feminine faces. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 273–280.

van der Eijk, C., Schmitt, H., & Binder, T. (2005). Left-right orientations and party choice. In J. Thomassen (Ed.), The European voter: A comparative study of modern democracies (pp. 167–191). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Winter, N. (2010). Masculine republicans and feminine democrats: Gender and American’s explicit and implicit images of the political parties. Political Behavior, 32, 587–618.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Vin Arceneaux, John Bullock, Martin Bisgaard, Matt Levendusky, Michael Bang Petersen, Josh Robison, Rune Slothuus, and Kim Mannemar Sønderskov as well as the editor and three anonymous reviewers for constructive inputs and suggestions on earlier versions of the article. The paper has previously been presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the International Society for Political Psychology, at the 2013 annual meeting of the Danish Political Science Association, in the Sidanius Lab (Harvard University), in the Center for Evolutionary Psychology (UC Santa Barbara), and in the section for political behavior and institutions (Aarhus University). The author thanks participants for their useful suggestions about the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laustsen, L. Choosing the Right Candidate: Observational and Experimental Evidence that Conservatives and Liberals Prefer Powerful and Warm Candidate Personalities, Respectively. Polit Behav 39, 883–908 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9384-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9384-2