Abstract

Worries about the instability of political attitudes and lack of ideological constraint among the public are often pacified by the assumption that individuals have stable political values. These political values are assumed to help individuals filter political information and thus both minimize outside influence and guide people through complex political environments. This perspective, though, assumes that political values are stable and consistent across contexts. This piece questions that assumption and argues that political values are socially reinforced—that is, that political values are not internal predispositions, but the result of social influence. I consider this idea with two empirical tests: an experimental test that recreates the transmission of political values and an observational analysis of the effect of politically homogeneous social contexts on political value endorsements. Results suggest that political values are socially reinforced. The broader implication of my findings is that the concepts scholars term “political values” may be reflections of individuals’ social contexts rather than values governing political behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While there is large body of literature on values (for example, the values that form moral foundations—see Graham et al. 2009), here my focus is on political values (Caprara and Vecchione 2013; Ciuk 2017; Feldman 1988, 2003, 2013; Feldman and Steenbergen 2001; Goren 2005; Goren et al. 2009; Hurwitz and Peffley 1987; Jacoby 2006, 2014; Knutsen 1995; Kuklinski 2001; McCann 1997; Nelson and Garst 2005; Nelson et al. 1997; Schwartz et al. 2010; Zaller 1992).

Research finds that political attitudes can be influenced by social and survey contexts (e.g., Bartels 2003; Chong and Druckman 2007; Nelson et al. 1997; Klar 2014; Sniderman and Theriault 2004; Tversky and Kahneman 1981), but the assumption is that political values are more stable (see Caprara and Vecchione 2013).

Although I use a value that has minimal partisan pre-treatment, there exists some general pre-treatment in that participants likely already had some views towards these values (see value distributions in preliminary studies). This may be beneficial, as it suggests the treatment led participants to change their perception of this value (rather than to initially develop it) in response to a social cue that branded compromise as endorsed by a positively-viewed political group. This speaks to the theory as values being socially reinforced rather than socially created.

The sample was: 48% female, 79% white, 51% college graduate or above; mean age of 38; 34% leaning, weak, or strong Republican, 13% pure Independent, and 53% leaning, weak, or strong Democrat; slightly skewed liberal (mean of 3.66 on scale from 1 to 7); above average in terms of interest in news (mean of 1.65 on scale from 1 to 3), taking part in political discussions (mean of 2.68 on scale from 0 to 7), and attention to news media (mean of 4.15 on scale from 0 to 7). Given this sample is above average in terms of education, interest, discussions, and attention to media, pretreatment is especially threatening (see Druckman and Leeper 2012), reinforcing the decision to use non-established political values. Lastly, a check was conducted on the sample to examine the influence of bots on the collected data, which found non-threatening results (see Online Appendix A.6).

Full question wording and results can be found in Online Appendixes A.2 and A.3.

The question wording for the dependent variable was: “What about you—which do you believe in more?” with the options of compromise, standing your ground, or don’t know.

The controls added as a robustness check to the findings were measured pre-treatment and included partisanship, ideology, gender, age, race, education, attention to news, how often one discusses of politics, and how often one consumes news. Wording of variables is in Online Appendix A.7. These controls aim to also address worries about partisan stereotyping (Rothschild et al. 2018).

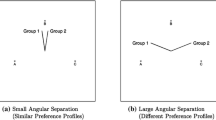

In general, research on political values that does not include all identified political values leads to the natural question of how political values differ from each other. It is likely, for example, that the internalization of political values among the public likely differs by how clear social cues are, just as attitudes among the public differ depending on elite signaling (see Levendusky 2010).

As in previous literature, morality is comprised of both moral tolerance and moral traditionalism.

Past research finds that in the 2000 ANES only 4% of respondents had networks in which everyone disagreed with them (e.g., a Democrat with a full network of Republicans), while 34% of respondents had networks in which everyone agreed with them and 48% of respondents had networks in which no one supported the other party’s candidate (Huckfeldt et al. 2004). Thus, I assume that a homogeneous network indicates a network of the same political party.

Note that given the smaller sample size (N = 227) here, the coefficient is marginally significant (p = 0.056).

I also conduct an analysis that examines the effect of political discussions (without accounting for the makeup of discussion partners) on the endorsement of party-congruent political values. This result largely mimics the results from the main analysis (see Appendix C).

References

Bartels, L. M. (2003). Democracy with attitudes. In M. B. MacKuen & G. Rabinowitz (Eds.), Electoral democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Berinsky, A. J. (2004). Can we talk? Self-presentation and the survey response. Political Psychology, 25(4), 643–659.

Berinsky, A. J., & Lavine, H. (2012). Self-monitoring and political attitudes. In J. Aldrich & K. M. McGraw (Eds.), Interdisciplinary innovation and the American national election studies (pp. 27–45). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Berlin, I. (1969). Four essays on liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, A., Gurin, G., & Miller, W. E. (1954). The voter decides. Evanston, IL: Row Peterson.

Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2013). Personality approaches to political behavior. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carlson, T. N., & Settle, J. E. (2016). Political chameleons: An exploration of conformity in political discussions. Political Behavior, 38, 817–859.

Caverley, J. D., & Krupnikov, Y. (2017). Aiming at doves: Experimental evidence of military images’ political effects. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(7), 1482–1509.

Chong, D. (2000). Rational lives: Norms and values in politics and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing public opinion in competitive democracies. American Political Science Review, 101(4), 637–655.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015.

Ciuk, D. J. (2017). Democratic values? A racial group-based analysis of core political values, partisanship, and ideology. Political Behavior, 39, 479–501.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822.

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and Discontent. New York: Free Press.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. The Adapted Mind, 163, 163–228.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Bros.

Druckman, J. N., & Leeper, T. J. (2012). Learning more from political communication experiments: Pretreatment and its effects. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 875–896.

Evans, G., & Neundorf, A. (2018). Core political values and the long-term shaping of partisanship in the British electorate. British Journal of Political Science, 1, 4. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000339.

Feldman, S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 416–440.

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: A theory of authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 24(1), 41–74.

Feldman, S. (2013). Political ideology. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, S., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2001). The humanitarian foundation of public support for social welfare. American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 658–677.

Gangestad, S. W., & Snyder, M. (2000). Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 126(4), 530–555.

Goffman, E. (1967). “On face-work, interaction ritual (pp. 5–45). New York: Pantheon.

Goren, P. (2005). Party identification and core political values. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 881–896.

Goren, P., Federico, C. M., & Kittilson, M. C. (2009). Source cues, partisan identities, and political value expression. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 805–820.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046.

Holtgraves, T. (1992). The linguistic realization of face management: Implications for language production and comprehension, person perception, and cross-cultural communication. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 141–159.

Huckfeldt, R. (1983). The social context of political change: Durability, volatility, and social influence. American Political Science Review, 77(4), 929–944.

Huckfeldt, R., Johnson, P. E., & Sprague, J. (2004). Political disagreement: The survival of diverse opinions within communication networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huckfeldt, R., Mondak, J. J., Hayes, M., Pietryka, M. T., & Reilly, J. (2013). Networks, interdependence, and social influence in politics. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (1987). How are foreign policy attitudes structured? A hierarchical model. The American Political Science Review, 81(4), 1099–1120.

Jacoby, W. G. (2006). Value choices and American public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 706–723.

Jacoby, W. G. (2014). Is there a culture war? Conflicting value structures in American public opinion. The American Political Science Review, 108(4), 754–771.

Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values, and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27(2), 163–182.

Kam, C. D., & Trussler, M. J. (2017). At the nexus of experimental and observational research: Theory, specification, and analysis of experiments with heterogeneous treatment effects. Political Behavior, 39(4), 789–815.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Klar, S. (2014). Partisanship in a social setting. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 687–704.

Klar, S., & Krupnikov, Y. (2016). Independent politics: How American disdain for parties leads to political inaction. Political Science Quarterly, 132(1), 191–193.

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., & Ryan, J. (2018). Affective polarization or partisan disdain? Untangling a dislike for the opposing party from a dislike of partisanship. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(6), 379–390.

Knutsen, O. (1995). Party choice. In J. W. Van Deth & E. Scarbrough (Eds.), The impact of values (pp. 460–491). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuklinski, J. H. (2001). Citizens and politics: Perspectives from political psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kuran, T. (1997). Private truths, public lies: The social consequences of preference falsification. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Lavine, H., & Snyder, M. (1996). Cognitive processes and the functional matching effect in persuasion: The mediating role of subjective perceptions of message quality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(6), 580–604.

Levendusky, M. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCann, J. A. (1997). Electoral choices and core value change: The 1992 presidential campaign. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 564–583.

Meyer, G. W. (1994). Social information processing and social networks: A test of social influence mechanisms. Human Relations, 47(9), 1013–1047.

Mutz, D. C. (1992). Impersonal influence: Effects of representations of public opinion on political attitudes. Political Behavior, 14(2), 89–122.

Mutz, D. C. (1998). Impersonal influence: How perceptions of mass collectives affect political attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mutz, D. C., & Mondak, J. J. (2006). The workplace as a context for cross-cutting political discourse. Journal of Politics, 68(1), 140–155.

Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. The American Political Science Review, 91(3), 567–583.

Nelson, T. E., & Garst, J. (2005). Values-based political messages and persuasion: Relationships among speaker, recipient, and evoked values. Political Psychology, 26(4), 489–515.

Peffley, M., Knigge, P., & Hurwitz, J. (2001). A multiple values model of political tolerance. Political Research Quarterly, 54, 379–406.

Rothschild, J. E., Howat, A. J., Shafranek, R. M., & Busby, E. C. (2018). Pigeonholing partisans: Stereotypes of party supporters and partisan polarization. Political Behavior, 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9457-5.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 550–562.

Schwartz, S. H., Caprara, G. V., & Vecchione, M. (2010). Basic Personal values, core political values, and voting: A longitudinal study. Political Psychology, 31, 421–452.

Seligman, C., & Katz, A. N. (1996). The dynamics of value systems. In C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 8). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sniderman, P. M., & Theriault, S. M. (2004). The structure of political argument and the logic of issue framing. In W. E. Saris & P. M. Sniderman (Eds.), Studies in public opinion (pp. 133–165). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stone, D. (2012). Policy paradox: The art of political decision-making (3rd ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Terkildsen, N. (1993). When white voters evaluate black candidates: The processing implications of candidate skin color, prejudice, and self-monitoring. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1032–1053.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458.

Valentino, N. A., & Nardis, Y. (2013). Political communication: Form and consequence of the information environment. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weber, C. R., Lavine, H., Huddy, L., & Federico, C. M. (2014). Placing racial stereotypes in context: Social desirability and the politics of racial hostility. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 63–78.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J., & Feldman, S. (1992). A simple theory of the survey response: Answering questions versus revealing preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 579–616.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Replication data for this paper can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/VYGJAM.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Connors, E. The Social Dimension of Political Values. Polit Behav 42, 961–982 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09530-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09530-3