Abstract

While partisan cues tend to dominate political choice, prior work shows that competing information can rival the effects of partisanship if it relates to salient political issues. But what are the limits of partisan loyalty? How much electoral leeway do co-partisan candidates have to deviate from the party line on important issues? We answer this question using conjoint survey experiments that characterize the role of partisanship relative to issues. We demonstrate a pattern of conditional party loyalty. Partisanship dominates electoral choice when elections center on low-salience issues. But while partisan loyalty is strong, it is finite: the average voter is more likely than not to vote for the co-partisan candidate until that candidate takes dissonant stances on four or more salient issues. These findings illuminate when and why partisanship fails to dominate political choice. They also suggest that, on many issues, public opinion minimally constrains politicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Gerber et al. (2011) is the closest comparison in prior work to our current study, but focuses on a different research question. Specifically, the study documents individual differences in the extent to which citizens are confident in their ability to assess policy proposals and, accordingly, reward or punish representatives for adopting positions on them.

Online Appendix B provides an example of how these profiles looked to respondents.

The race/ethnicity of the candidate profiles was weighted to resemble the distribution of members of Congress at the time the survey was run.

Because of our focus on choice in settings with opposing party candidates we exclude 10,778 profile pairs in which the candidates had the same party label and individuals were unable to choose between them on this factor.

For this analysis we are only able to examine up to 4 issue agreements because one candidate position item (immigration policy) could not be mapped back to the individual policy position question.

We note here that there is minimal heterogeneity in these results by party, see Online Appendix D.

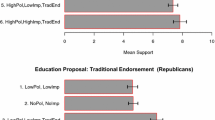

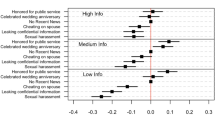

The analysis in Fig. 1 does not differentiate between different types of issues. When we consider their influence separately in Online Appendix A, agreement on Obamacare is more influential than the other three issues, although all exert a substantial influence on candidate choice.

These results characterize the response of the average partisan in our experiment. For brevity, we may refer to “voters,” “respondents” or “individuals” in the aggregate throughout.

In keeping with this assertion, Chong and Mullinix (n.d.) find that policy information has the greatest impact on policy support if it contains information on the ideological direction of the proposal.

While self-reports placed the Birth Control issue as high-salience for Study 1, our approach in Study 2 categorizes it as minimally divisive.

See Online Appendix B for additional information on the pre-testing procedure and validation of this issue typology.

These dynamics are similar when examining support for out-party candidates, but there is a substantially lower baseline level of support across conditions. These results are presented in Online Appendix D

This sample only included ‘Strong’ or ‘Not very strong’ partisans, excluding partisan leaners and independents.

For instance, comparing the ideology of general election candidates for Congress using measures of ideology based on a candidate’s campaign finance receipts, shows that no races in 2014 (the most recent year available) involved a Democratic candidate that was more conservative than their Republican opponent (Bonica 2014).

As in other work, we include partisan “leaners” with the party they are closest with and exclude “pure” independents.

References

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ansolabehere, S., Rodden, J., & Snyder, J. M. (2006). The strength of issues: Using multiple measures to gauge preference stability, ideological constraint and issue voting. American Political Science Review, 102(2), 215–232.

Arceneaux, K. (2008). Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Political Behavior, 30(2), 139–160.

Arceneaux, K., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2017). Taming intuition: How reflection minimizes partisan reasoning and promotes democratic accountability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barber, M., & Pope, J. C. (2019). Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 38–54.

Bartels, L. M. (2000). Partisanship and voting behavior, 1952–1996. American Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 35–50.

Bolsen, T., Druckman, J. N., & Cook, F. L. (2014). The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior, 36(2), 235–262.

Bonica, A. (2014). Mapping the ideological marketplace. American Journal of Political Science, 58(2), 37–386.

Boudreau, C., Elmendorf, C., & MacKenzie, S.A. (n.d.) Roadmaps to representation: An experimental study of how voter education tools affect citizen decision making. Political Behavior (pp. 1–24).

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2014). Informing the electorate? How party cues and policy information affect public opinion about initiatives. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 48–62.

Boudreau, C., & MacKenzie, S. A. (2018). Wanting what is fair: How party cues and information inequality affect public support for taxes. Journal of Politics, 80(2), 367–381.

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 496–515.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. New York: Wiley.

Canes-Wrone, B., Brady, D. W., & Cogan, J. F. (2002). Out of step, out of office: Electoral accountability and house members’ voting. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 127–140.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1980). The two faces of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 74(1), 78–91.

Carsey, T. M., & Layman, G. C. (2006). Changing sides or changing minds? Party identification and policy preferences in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 464–477.

Chong, D., & Mullinix, K.J. (n.d.) Information and issue constraints on party cues. American Politics Research. Forthcoming.

Ciuk, D. J., & Yost, B. A. (2016). The effects of issue salience, elite influence, and policy content on public opinion. Political Communication, 33(2), 328–345.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic Theory of democracy. Manhattan: Harper & Row.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Fowler, A. (n.d.) Partisan intoxication or policy voting? Quarterly Journal of Political Science. Forthcoming. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1StjsBztpHTYDErcKbgjNk0ujWXXDxb7O.

Gerber, A., & Green, D. (1999). Misperceptions about perceptual bias. Annual Review of Political Science, 2(1), 189–210.

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., & Dowling, C. M. (2011). Citizens’ policy confidence and electoral punishment: A neglected dimension of electoral accountability. The Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1206–1224.

Gilens, M. (2001). Political ignorance and collective policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(2), 379–396.

Gooch, A., & Huber, G. A. (2018). Exploiting Donald Trump: Using candidates’ positions to assess ideological voting in the 2016 and 2008 presidential elections. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 48(2), 342–356.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey expeirments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(8), 2395–2400.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109, 1–17.

Iyengar, S., Hahn, K. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Walker, J. (2008). Selective exposure to campaign communication: The role of anticipated agreement and issue public membership. Journal of Politics, 70(1), 186–200.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 129–146.

Jessee, S. A. (2012). Ideology and spatial voting in American elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kam, C. D. (2005). Who toes the party line? Cues, values and individual differences. Political Behavior, 27(2), 163–182.

Key, V. O. (1961). Public opinion and American Democracy. New York: Knopf.

Kim, H. A., & LeVeck, B. L. (2013). Money, reputation, and incumbency in US house elections, or why marginals have become more expensive. American Political Science Review, 107(3), 492–504.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirkland, P., & Coppock, A. (2018). Candidate choice without party labels: New insights from U.S. mayoral elections 1945–2007 and conjoint survey experiments. Political Behavior, 40(3), 571–591.

Lavine, H. G., Johnston, C. D., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2012). The ambivalent partisan: How critical loyalty promotes democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leeper, T., & Robison, J. (n.d.) More important, but for what exactly? The insignificant role of subject issue importance in vote decisions. Political Behavior. Forthcoming.

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Malhotra, N., & Kuo, A. G. (2008). Attributing blame: The public’s response to Hurricane Katrina. The Journal of Politics, 70(1), 120–135.

Mason, L. (2015). I disrespectfully agree: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59, 128–145.

Messing, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2014). Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research, 41(8), 1042–1063.

Mummolo, J. (2016). News from the other side: How topic relevance limits the prevalence of partisan selective exposure. The Journal of Politics, 78(3), 763–773.

Mummolo, J., & Nall, C. (2017). Why partisans do not sort: The constraints on political segregation. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 45–59.

Mummolo, J., & Peterson, E. (2017). How content preferences limit the reach of voting aids. American Politics Research, 45(2), 159–185.

Mummolo, J., & Peterson, E. (2019). Demand effects in survey experiments: An empirical assessment. American Political Science Review, 113, 517–529.

Nicholson, S. P. (2011). Dominating cues and the limits of elite influence. Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1165–1177.

Nicholson, S. P. (2012). Polarizing cues. American Journal of Political Science, 56(1), 52–66.

Nicholson, S. P., & Hansford, T. G. (2014). Partisans in robes: Party cues and public acceptance of supreme court decisions. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 620–636.

Peterson, E. (2017). The role of the information enviornment in partisan voting. Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1191–1204.

Peterson, E. (2019). The scope of partisan influence on policy opinion. Political Psychology, 40(2), 335–352.

Petty, R., & Krosnick, J. (1995). Attitude strength: Antecendents and consequences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rahn, W. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 472–496.

Riggle, E. D. (1992). Cognitive strategies and candidate evaluations. American Politics Quarterly, 20(2), 227–246.

Riggle, E. D., Ottati, V., Wyer, R., & Kuklinski, J. (1992). Bases of political judgements: The role of stereotypic and nonsteroetypic information. Political Behavior, 14, 67–87.

Sears, D. (1975). Political socialization. In F. I. Greenstein & N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of political science (Vol. 2, pp. 95–153). Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Tesler, M. (2015). Priming predispositions and changing policy positions: An account of when mass opinion is primed or changed. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 806–824.

Tomz, M., & Van Houweling, R. P. (2009). The electoral implications of candidate ambiguity. American Political Science Review, 103(1), 83–98.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J. (2012). What nature and origins leaves out. Critical Review, 24(4), 569–642.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jeremy Ferwerda, Martin Gilens, Justin Grimmer, Greg Huber, Lilliana Mason, Lilla Orr, Markus Prior and Lauren Wright for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Replication data are on the Political Behavior Dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/J9IJGM

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mummolo, J., Peterson, E. & Westwood, S. The Limits of Partisan Loyalty. Polit Behav 43, 949–972 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09576-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09576-3