Abstract

Declining trust in government is often cited as the cause of declining support for policies that require ideological sacrifices. Yet pivotal to the effect of trust is the broader political context, which can vary over time. In a context of deep partisan divisions, for individuals who do not trust the government, even small ideological costs can signal the beginning of a process that leads to much larger ideological costs down the line—a process akin to a “slippery slope.” We demonstrate the conditional relationship between partisan divides, governmental trust, and support for policy through empirical tests that focus on the case of gun control. We first show that the effect of trust in government on conservatives’ gun control attitudes increases as polarization over the issue grows. We then use a continuum of gun control policies to demonstrate that the effect of trust on policy support can follow a slippery slope structure during polarized points.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

When we consider shifts in trust during changes in administration, we look at the 2008–2009 ANES panel study. Fifty-eight percent of respondents do not change their answer to the trust question from the first wave (February 2008, when Republican George W. Bush is president) to the last wave (July 2009, when Democrat Barack Obama is president). Only about 6% of respondents change their answer more than 1 place on the 5-point trust scale. The partisan difference in mean trust grows from .11 (on a 1–5 scale) in 2008 to .35 in 2009. Republicans are more trusting under Bush while Democrats are more trusting under Obama. Hence, there is some relationship between trust and the occupant of the White House, but trust is not just a measure of presidential support. We include controls for individual-level presidential approval and congressional approval as is standard practice in studies on trust.

Rudolph and Evans (2005) for example, rely on measures that ask people whether they generally support more or less spending for “Maintaining a strong military defense”, “Protecting the environment and natural resources”, etc.

It is possible that trust in government instead works by increasing support for individual policies in isolation—that trust increases support for policy A without any consideration of policy B. We would then expect those with low trust in government to be less supportive of any policy that differs from their ideal point compared to those with high trust in government. Conversely, if trust does indeed function by alleviating concerns of the slippery slope, it should only increase policy support for moderate policies that could be the first step toward more extreme and unwanted policies (Fig. 1, Case 2).

Hetherington and Rudolph (2015) argue that polarization can also generally erode trust because polarization leads people to believe that divides at the elite level will lead to poor government performance. This argument would lead to the same slippery slope conclusion as the one proposed here. Polarization can lead to a decline in trust and can lead a person to believe that a party’s ultimate goal is a more extreme policy than the one they have proposed. In turn, this combination of low trust and perceived goals of extremity are likely to leave a person unlikely to want to sacrifice even for a moderate policy.

Lacombe’s (2019) focus is on communication to NRA membership, which suggests that these NRA efforts may be especially powerful for strong conservatives who may receive messaging directly from NRA.

An important question is whether the differentiation on gun control that has taken place within the public is sorting or polarization. There is reason to believe that it is sorting. Joslyn et al. (2017) document a process by which gun-owners became consistently more likely to vote Republican. Similarly, Levendusky (2010) suggests that polarization among elites leads the public to be more consistent across issues—a signal of sorting. Fiorina (2016) classifies the process as sorting and Miller (2019) argues that sorting more clearly explains patterns in emerging public divides on gun control. A confounding factor is that sorting can produce the appearance of increasing polarization (Fiorina 2016). That being said, our argument rests less on the process by which partisan divisions have occurred, than in the outcome of these divisions: that people are able to identify each party’s preferences on gun control.

We note the possibility that slippery slope reasoning is functioning in two ways: a priori (worry about the slippery slope leads to policy dislike) or post-hoc (there is an immediate dislike of the policy that leads to a slippery slope rationalization). Although it is possible that for some people the process is post-hoc, slippery slope reasoning is generally accessible enough to people that a priori considerations are likely. This is especially true in policy areas—such as gun control—where the slippery slope outcomes are all categorically similar, facilitating easier slippery slope reasoning (Corner et al. 2011).

The data is publicly available at https://electionstudies.org/data-center/ and https://wc.wustl.edu/taps-data-archive. The code for replicating the analysis is available at the Political Behavior dataverse: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/MHLM6J.

The American Panel Survey is conducted by The Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy at Washington University in St. Louis. Online surveys are conducted monthly by GfK/Knowledge Networks.

The lowest percentage of respondents calling for weaker gun laws was in 2004 at 3.3%. The highest percentage was in 2016, but, even then, it was only 6.5%.

The ANES variable guide notes that to be coded as “Never” a respondent had to volunteer this response option on their own.

Distributions for different wordings of the trust variable are available in Online Appendix C.

There are arguments to suggest that ideology is no longer a set of policy values, but rather an identity (e.g. Kinder and Kalmoe 2017). On the other hand, however, there is recent research to suggest that people do have ideological beliefs that can be stronger than their partisan pre-dispositions (Orr and Huber 2019).

In this analysis, we do not include a gun owner measure because it is not available in all years. Models including a control for gun ownership when available are included in Online Appendix E.

The effect in 2012 is statistically significant only in a one-tailed test.

There are a number of reasons why this pattern emerges starting 2008. Despite gun control being a relatively consistent part of the Republican agenda, the issue may have nationalized (Garlick 2017). Also, 2008 surveys are conducted at a time when voters anticipate a shift from a Republican to a Democratic presidency. Finally, increasing partisan antipathy sets a context for greater divides. Although determining which factors increase partisan divides is important, empirically adjudicating between these explanations is beyond the goals of this particular manuscript.

The year 2000 is coded 1, 2004 is coded 2, 2008 is coded 3, 2012 is coded 4, and 2016 is coded 5.

We should note that while there are party differences in explicit trust in government, which we are using here, there are smaller party differences in implicit trust in government (Intawan and Nicholson 2018). This is possible because explicit trust brings to mind specific government actions while implicit trust captures support of the system of government.

We do not include a measure of racial resentment as these questions were not asked by TAPS.

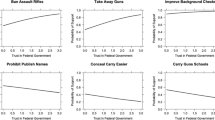

The goal is that items are ordered such that if a respondent supports a strong restriction on guns then the same respondent ought to support lesser restrictions on guns. If a respondent supports three out of five policies, then the respondent should support the three least restrictive policies not the three most restrictive policies.

We also validate this order using Invariant Item Ordering (IIO) analysis which yields the same results (Ligtvoet et al. 2010).

References

Berinsky, A. J. (2007). Assuming the costs of war: Events, elites, and American public support for military conflict. The Journal of Politics, 69(4), 95–997.

Berry, W. D., Demeritt, J. H. R., & Esarey, J. (2010). Testing for interaction in binary logit and probit models: Is a product term essential? American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 248–266.

Binder, S. (2015). The dysfunctional congress. Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 85–101.

Buttice, M., Huckfeldt, R., & Ryan, J. B. (2009). Polarization, attribution and communication networks in the 2006 congressional elections. In J. J. Mondak & D.-G. Mitchell (Eds.), Fault lines: Why the Republicans Lost Congress (pp. 42–60). New York: Routledge.

Chanley, V. A., Rudolph, T. J., & Rahn, W. M. (2000). The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(3), 239–256.

Cook, P. J., & Goss, K. A. (2014). The gun debate: What everyone needs to know. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cook, T. E., & Gronke, P. (2005). The skeptical American: Revisiting the meanings of trust in government and confidence in institutions. The Journal of Politics, 67(3), 784–803.

Corner, A., Hahn, U., & Oaksford, M. (2011). The psychological mechanism of the slippery slope argument. Journal of Memory and Language, 64(2), 133–152.

Enoch, D. (2001). Once you start using slippery slope arguments you’re on a very slippery slope. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 21(4), 629–647.

Filindra, A., & Kaplan, N. J. (2015). Racial resentment and whites’ gun policy preferences in contemporary America. Political Behavior, 38(2), 255–275.

Fiorina, M. P. (2016). Has the American Public Polarized? Hoover Institution Essay on American Politics. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/fiorina_finalfile_0.pdf

Garlick, A. (2017). National policies, agendas and polarization in American state legislatures: 2011 to 2015. American Politics Research, 45(6), 939–979.

Gilpin, D. (2019). NRA media and second amendment identity politics. In A. Nadler (Ed.), News on the right: Studying conservative news cultures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goss, K. A. (2004). Policy, politics and paradox: The institutional origins of the great American gun war. Fordham Law Review, 73(2), 681–714.

Guttman, L. (1944). A basis for scaling qualitative data. American sociological review, 9(2), 139–150.

Haider-Markel, D. P., & Joslyn, M. L. (2001). Gun policy, opinion, tragedy, and blame attribution: The conditional influence of issue frames. The Journal of Politics, 63(2), 20–543.

Haigh, M., Wood, J. S., & Stewart, A. J. (2016). Slippery slope arguments imply opposition to change. Memory and Cognition, 44(5), 819–836.

Harris, J. (2015). Edited genes and slippery slopes: Dilemmas in the ethics of gene editing. Ethics in Biology, Engineering and Medicine: An International Journal, 6(3–4), 281.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808.

Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hetherington, M. J. (2015). Why polarized trust matters. The Forum. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2015-0030.

Hetherington, M., & Globetti, S. (2002). Politica trust and racial policy preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 253–275.

Hetherington, M. J., & Husser, J. A. (2012). How trust matters: The changing political relevance of political trust. American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 312–325.

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won't work: Polarization, political trust, and the governing crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Intawan, C., & Nicholson, S. P. (2018). My trust in government is implicit: Automatic trust in government and system support. The Journal of Politics, 80(2), 601–614.

Joslyn, M. R., Haider-Markel, D. P., Baggs, M., & Bilbo, A. (2017). Emerging political identities? Gun ownership and voting in presidential elections. Social Science Quarterly, 98(2), 382–396.

Karol, D. (2009). Party position change in American politics: Coalition management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keele, L. (2005). The authorities really do matter: Party control and trust in Government. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 873–886.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. (2017). Neither Liberal Nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public. University of Chicago Press.

Kreitzer, R. J., Hamilton, A. J., & Tolbert, C. J. (2014). Does policy adoption change opinions on minority rights? The effects of legalizing same-sex marriage. Political Research Quarterly, 67(4), 795–808.

Lacombe, M. (2019). The Political weaponization of gun owners: The NRA’s cultivation, dissemination, and use of group social identity. The Journal of Politics, 81(4), 1342–1356.

LaFolette, H. (2005). Living on a slippery slope. Journal of Ethics, 9(3/4), 475–499.

Lawrence, R. G., & Birkland, T. A. (2004). Guns Hollywood and school safety: Defining the school-shooting problem across public arenas. Social Science Quarterly, 85(5), 1193–1207.

Levendusky, M. (2009). The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131.

Levendusky, M. S., & Malhotra, N. (2016). (Mis)perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 378–391.

Lewis, P. (2007). The empirical slippery slope from voluntary to non-voluntary euthanasia. The Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, 35(1), 197–210.

Ligtvoet, R., Van der Ark, L. A., Te Marvelde, J. M., & Sijtsma, K. (2010). Investigating an invariant item ordering for polytomously scored items. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 578–595.

Loevinger, J. (1948). The technic of homogeneous tests compared with some aspects of “scale analysis" and factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 45(6), 507.

Lyons, J., & Sokhey, A. E. (2017). Discussion networks, issues, and perceptions of polarization in the American electorate. Political Behavior, 39(4), 967–988.

Marietta, M. (2008). From my cold, dead hands: Democratic consequences of sacred rhetoric. Journal of Politics, 70(3), 767–779.

Miller, A. H. (1974). Political issues and trust in government: 1964–1970. American Political Science Review, 68(3), 951–972.

Miller, S. (2019). What Americans think about gun control: Evidence from the General Social Survey, 1972–2016. Social Science Quarterly, 100(1), 272–288.

Mokken, R. J. (1971). A theory and procedure of scale analysis: With applications in political research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Mondak, J., & Anderson, M. R. (2004). The knowledge gap: A re-examination of gender-based differences in political knowledge. Journal of Politics, 66(2), 492–512.

Orr, L., & Huber, G. (2019). The policy basis of measured partisan animosity in the United States. American Journal of Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12498.

Rudolph, T. (2009). Political trust, ideology, and public support for tax cuts. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(1), 144–158.

Rudolph, T. J., & Evans, J. (2005). Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 660–671.

Rudolph, T. J., & Popp, E. (2009). Bridging the ideological divide: Trust and support for social security privatization. Political Behavior, 31, 331–351.

Schneider, S. K., Jacoby, W. G., & Lewis, D. C. (2010). Public opinion toward intergovernmental policy responsibilities. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 41(1), 1–30.

Sheff, E. (2011). Polyamorous families, same-sex marriage and the slippery slope. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 40(5), 487–520.

Sijtsma, K., & Molenaar, I. W. (2002). Introduction to nonparametric item response theory (Vol. 5). Thousand Oak: Sage.

Verbakel, E., & Jaspers, E. (2010). A comparative study on permissiveness toward euthanasia: Religiosity, slippery slope, autonomy and death with dignity. Public Opinion Quarterly., 74(1), 109–139.

Volokh, E. (2003). The mechanisms of the slippery slope. Harvard Law Review, 116(4), 1026–1137.

Wolpert, R. M., & Gimpell, J. G. (1998). Self-interest, symbolic politics, and public attitudes toward gun control. Political Behavior, 20(3), 241–262.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ryan, J.B., Andrews, T.M., Goodwin, T. et al. When Trust Matters: The Case of Gun Control. Polit Behav 44, 725–748 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09633-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09633-2