Abstract

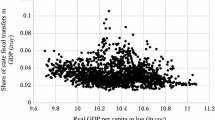

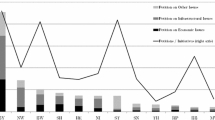

We study the consequences of franchise extension and ballot reform for the size of government in Western Europe between 1820 and 1913. We find that franchise extension exhibits a U-shaped association with revenue per capita and a positive association with spending per capita. Instrumental variables estimates, however, suggest that the U-shaped relationship may be non-causal and our fixed effects estimates point to substantial cross-country heterogeneity. Further, we find that the secret ballot did not matter for tax revenues per capita but might have expanded the size of government relative to GDP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

He defines limited government as being established in the year that parliament gains the constitutional right to control the national budget on an annual basis and had had that right for at least two consecutive decades (Dincecco 2011:28).

Meltzer and Richard (1981) build on the median voter model. This model is not ideal for thinking about complex fiscal systems with many policy dimensions. Hettich and Winer (1999) and Tridimas and Winer (2005), however, show that the franchise extension hypothesis holds within the context of the more appropriate probabilistic voting model.

Persson and Tabellini (2003) have demonstrated that the election rule (majoritarian versus proportional rule) and the distinction between presidential and parliametarian democracies exert important influences on the size and composition of the public finances in the modern period (after World War II). All of the countries in our sample, with the exception of Belgium where proportional rule was introduced in 1894, employed majority rule until 1913. This makes it impossible to use our data to study the effect of the election rule on growth in government.

Stokes (2005), in an interesting study of electoral corruption in Argentina in the 1990s, shows that vote markets can operate even under secret ballot. Yet, it is clear that secrecy makes it more difficult to trade votes.

Sabine (1966) illuminates this logic very clearly in his analysis of the British income tax.

See Aidt and Dutta (2007) for theoretical analysis of the relationship between economic growth and growth in the relative size of government.

Another structural explanation for growth government—Baumol’s cost disease explanation—emphasizes the limited scope for productivity growth in the production of public services (Baumol 1967). The cost inflation that follows from wage growth in the private sector then pushes up government expenditures. Yet another theory centers on variations in the deadweight cost of taxation (Becker 1983; Becker and Mulligan 2003; Aidt 2003). We are unable to test these explanations with the data at hand.

Since we cannot trace all variables back to 1820 for all nations and because some of the countries were created within the sample period, the resulting panel is unbalanced consisting of 655–670 observations. The entry and exit years for each country are listed in column one of Table 2.

Unified in 1861.

Data from 1820 refer to the geographical unit comprised of Austria-Hungary.

Independent of the Kingdom of Netherlands in 1831.

Data from 1820. For the period 1820 to 1831, the fiscal data exclude the net transfer from what in 1831 becomes Belgium.

Independent polity in 1820, but fiscal data not available until 1864.

Prussia exits the sample in 1867 prior to the creation of the German Empire in 1871.

Norway was in union with Sweden until 1905. However, it had its own parliament (Storting) from 1815. The parliament decided on taxation and expenditure (except for military spending). Foreign policy was, in contrast, controlled by the Swedish King (and parliament). This justifies treating Norway as an independent unit for the purpose of studying the evolution of the size of government.

The source for these data is Flora et al. (1983).

The data refer to the right to vote in parliamentary elections to the lower chamber. Prussia had a franchise that divided voters into three classes according to tax payment. Although more than 80 % of adult males could vote in the third class, this group of voters had little influence on who got elected and, based on data from Kock (1984:Table 3a) and census data, we define suffrage as the percentage of voters in classes one and two relative to the adult male population. Austria had a system based on a number of Curia (the members of which elected a subset of the members of parliament). We define suffrage using voters in Curia III and IV (electing 70 % of the seats) until 1891 and Curia V after that. For the other countries, the franchise to the lower chamber was almost equal and we have not made any adjustments. The source of these data is Kock (1984), Flora et al. (1983) and own coding as explained in Aidt and Jensen (2011).

The first European country to grant voting rights to women was Finland (which is not in our samples) in 1906. Norwegian women who either themselves or whose husbands had income or wealth above a certain threshold were allowed to vote from 1909 onwards, but full women’s suffrage was not achieved until 1913. In contrast, it was not uncommon for US states on the frontier to grant voting rights to women before the turn of the nineteenth century and New Zealand was also amongst the frontrunners by granting the vote to women in 1869.

The Australian ballot requires that an official ballot is printed at public expense and distributed only at the polling stations. The official ballot lists the names of the nominated candidates of all parties and it is marked in secret at the polling station.

Aidt and Jensen (2012) provide detailed justifications for the code choices.

The five aspects are: (i) constraints on the executive, (ii) competitiveness, (iii) openness in the process of executive recruitment, (iv) competitiveness and (v) regulation of political participation. The sum of the scores on the components is used to construct two summary variables, measuring democracy on a scale from 0 to 10 and autocracy from −10 to 0. The polity index is the sum of these two, and thus ranges from −10 (autocracy) to +10 (fully developed democratic institutions). In the estimations, we use the polity2 index, which is the version of the polity index that has been adjusted to make it suitable for time series analysis.

Vreeland (2008) constructs the x-polity index by adding up the scores on the three sub-components that refer to the executive and excluding the two sub-components related to political participation.

The source of these data is Singer and Small (1994) or http://www.correlatesofwar.org/.

None of these socioeconomic variables are recorded with the same accuracy as we expect from modern data and thus are measured with substantial errors. GDP data, for example, are constructed from production data and often not on an annual basis. Other data are constructed from periodic censuses. The quality of the data improves towards the end of the sample period. This makes it a challenge to test the secondary hypotheses which we have put forward.

We also consulted EH.net encyclopedia (eh.net/encyclopedia).

These dummies are significant in all specifications reported below.

As pointed out by Congleton (2011:p. 263), left-wing parties were often left-liberals, rather than revolutionary reformers.

Judson and Owen (1999) show that the bias is very small in panels with more than 20 years of data. We have, as a robustness check, re-estimated the partial adjustment model on both samples with the bias-corrected least-squares dummy variable (LSDV) estimator proposed by Bruno (2005a, 2005b). The point estimates are virtually the same as those reported in the text, but the standard errors are larger. The LSDV estimator is preferable to the GMM estimator proposed by Arellano and Bond (1991) in panels with few cross section units.

In practice, we allow for country-specific first order serial correlation. The estimated coefficients are all small. Panel unit root tests reject that the errors have unit roots.

To be precise, revolutionary threat for country i in year t is defined as

$$ \sum_{j\neq i}W_{ij}R_{jt} $$where R jt is an indicator variable equal to one if country j (different from i) is affected by a major revolutionary event in year t and W ij is the inverse distance in kilometers between the capitals of country i and j. We note that we exclude revolutionary events in country i itself from the calculations.

A complementary mechanism is that those who are seeking a regime change through revolution might take inspiration from events in other countries. In particular, revolutions abroad could serve as rallying cries and help revolutionaries or other regime opponents at home to coordinate their actions effectively and transform sporadic discontent into a serious and well-organized regime challenge.

Przeworski (2009) also establishes a strong correlation between proxies for the threat of revolution and suffrage extension, but for the period after World War I.

This would be consistent with Acemoglu and Robinson’s (2000) theory which stresses that the elites will prefer to offer such transfers temporarily if that is sufficient to avoid a revolution. Since they cannot commit to such transfers in the absence of a credible threat, they are often insufficient, and the elites will then have to extend the franchise and in that way commit themselves to future transfers.

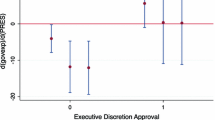

The variance of the estimated marginal effect of suffrage is:

$$ \operatorname {var}(\hat{\beta}_{1})+4(\mathit{suffrage})^{2}\operatorname {var}(\hat{ \beta}_{2})+4(\mathit{suffrage})\operatorname {cov}(\hat{\beta}_{1},\hat{ \beta}_{2}). $$This is used to compute 95 % confidence intervals, using the point and variance estimates from column two of Table 3.

We show only the first stage regressions for suffrage since the ones for suffrage squared are of little economic interest. We note, however, that the instruments are jointly significant with a high F-statistic and that they pass the over-identification test.

Revenue and spending data measured in gold grams are not available for Norway and Switzerland. The sample underlying these estimations therefore excludes these countries, but includes Austria and Belgium.

Some well-known studies, e.g., Kristov et al. (1992), Becker and Mulligan (2003), Kenny and Winer (2006) and Ferris et al. (2008) are not included in Table 7. This is either because they do not include franchise extension variables or because they do not include direct tests of the two hypotheses of interest to us. Likewise, we do not include studies that focus on women’s suffrage in the overview.

We notice that Lindert (1994, 2004b) also studies a relatively short sample running from 1880 to 1930. Yet, he finds evidence of retrenchment. We conjecture that this is because his sample includes a number of non-democracies in Latin America as well as Japan. Since he uses between-country variation to estimate the effects, he can compare social spending by these non-democracies to the elite/middle class democracies in Europe during the late 19th century.

To be precise, Boix (2001) shows that the impact of a binary index of democracy on the size of government is conditional on the level of development and that the positive effect is present above a certain GDP per capita threshold.

Kim (2007) uses data on local strikes as an instrument for the suffrage. These data are available for a few countries from 1880, but are not recorded for the majority until the turn of the century. Aidt and Jensen (2009a, 2009b) use an instrument similar to the one we employ here, i.e., revolutionary events in other countries. Aidt and Jensen (2009a) cover a large portion of the 19th century, whereas Aidt and Jensen (2009b) start in 1860.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2000). Why did the West extend the franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic origins of dictatorship and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aidt, T. S. (2003). Redistribution and deadweight costs: the role of political competition. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(2), 205–226.

Aidt, T. S., & Dutta, J. (2007). Policy myopia and economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(3), 734–753.

Aidt, T. S., & Dallal, B. (2008). Female voting power: the contribution of women’s suffrage to the growth of social spending in Western Europe, 1869–1960. Public Choice, 134(3), 391–417.

Aidt, T. S., & Eterovic, D. (2011). Political competition, participation and public finance in 20th Century Latin America. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(1), 181–200.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2009a). The taxman tools up: an event history study of the introduction of the Income Tax. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 160–175.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2009b). Tax structure, size of government, and the extension of the voting franchise in Western Europe, 1860–1938. International Tax and Public Finance, 16(3), 362–394.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2011). Workers of the world, unite! Franchise extensions and the threat of revolution in Europe, 1820–1938 (CESifo Working Paper series No. 3417). CESifo, University of Munich, Germany.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2012). From open to secret ballot. Vote buying and modernization (Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 1221). Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge, U.K.

Aidt, T. S., Dutta, J., & Loukoianova, E. (2006). Democracy comes to Europe: franchise extension and fiscal outcomes, 1830–1938. European Economic Review, 50(2), 249–283.

Aidt, T. S., Daunton, M., & Dutta, J. (2010). The retrenchment hypothesis and the extension of the franchise in England and Wales. The Economic Journal, 120(547), 990–1020.

Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przeworski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development, 31(2), 3–36.

Anderson, G. M., & Tollison, R. D. (1990). Democracy in the marketplace. In W. M. Crain & R. D. Tollison (Eds.), Predicting politics: essays in empirical Public Choice (pp. 285–303). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Baland, J.-M., & Robinson, J. A. (2007). How does vote buying shape the economy. In F. C. Schaffer (Ed.), Elections for sale: the causes and consequences of vote buying (pp. 123–141). Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Baland, J.-M., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). Land and power: theory and evidence from Chile. The American Economic Review, 98(5), 1737–1765.

Baumol, W. (1967). The macroeconomics of unbalanced growth. The American Economic Review, 57(3), 415–426.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. The American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Becker, G. S. (1983). A theory among pressure groups for political influence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(3), 371–400.

Becker, G. S., & Mulligan, C. B. (2003). Deadweight costs and the size of government. The Journal of Law & Economics, 46(2), 293–340.

Becker, S. O., & Woessmann, L. (2010). The effect of Protestantism on education before the industrialization: evidence from 1816 Prussia. Economics Letters, 107(2), 224–228.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2011). Pillars of prosperity. The political economics of development clusters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Boix, C. (2001). Democracy, development and the public sector. American Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 1–17.

Boix, C. (2003). Democracy and redistribution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Borcherding, T. E. (1985). The causes of government expenditure growth: a survey of the US evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 28(3), 359–382.

Bruno, G. S. F. (2005a). Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters, 87(3), 361–366.

Bruno, G. S. F. (2005b). Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel-data models with a small number of individuals. Stata Journal, 5(4), 473–500.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101.

Congleton, R. D. (2007). From royal to parliamentary rule without revolution: the economics of constitutional exchange within divided governments. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 261–284.

Congleton, R. D. (2011). Perfecting parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collier, P., & Vicente, P. C. (2012). Violence, bribery, and fraud: the political economy of elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Choice, 153(1–2), 117–147.

Dincecco, M. (2009). Fiscal centralization, limited government, and public revenues in Europe, 1650–1913. The Journal of Economic History, 69(1), 48–103.

Dincecco, M. (2011). Political transformations and public finances, Europe 1650–1913. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dincecco, M., & Prado, M. (2012). Warfare, fiscal capacity and performance. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(3), 171–203.

Dincecco, M., Federico, G., & Vindigni, A. (2011). Warfare, taxation, and political change: evidence from the Italian Risorgimento. The Journal of Economic History, 71(4), 887–914.

Engerman, S., & Sokoloff, K. (2005). The evolution of suffrage institutions in the new world. The Journal of Economic History, 65(4), 891–921.

Engerman, S., & Sokoloff, K. (2011). Economic development in the Americas since 1500: endowments and institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferris, J. S., Park, S.-B., & Winer, S. (2008). Studying the role of political competition in the evolution of government size over long horizons. Public Choice, 137(1–2), 369–401.

Flora, P., Alber, J., Eichenberg, R., Kohl, J., Kraus, F., Pfenning, W., & Seebohm, K. (1983). State, economy and society 1815–1975 (Vol. I). Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

Gundlach, E., & Paldam, M. (2009). A farewell to critical junctures: sorting out long-run causality of income and democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 25(3), 340–354.

Hausken, K., Martin, C. W., & Plümper, T. (2004). Government spending and taxation in democracies and autocracies. Constitutional Political Economy, 15(3), 239–259.

Heckelman, J. C. (1995). The effect of the secret ballot on voter turnout rates. Public Choice, 82(1–2), 107–124.

Hettich, W., & Winer, S. L. (1999). Democratic choice and taxation: a theoretical and empirical analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Higgs, R. (1987). Crisis and leviathan: critical episodes in the growth of American government. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hobsbawm, E. (1962). The age of revolution, 1789–1848. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Holsey, C. M., & Borcherding, T. E. (1997). Why does government’s share of national income grow? An assessment of the recent literature on the U.S. experience. In D. C. Mueller (Ed.), Perspectives on public choice. A handbook (pp. 342–370). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Husted, T. A., & Kenny, L. W. (1997). The effect of the expansion of the voting franchise on the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 105(1), 54–82.

Judson, R. A., & Owen, A. L. (1999). Estimating dynamic panel data models: a practical guide for macroeconomists. Economics Letters, 65(1), 9–15.

Kenny, L. W., & Winer, S. L. (2006). Tax systems in the world: an empirical investigation into the importance of tax bases, administration costs, scale and political regime. International Tax and Public Finance, 13(2–3), 181–215.

Kim, W. (2007). Social insurance expansion and political regime dynamics in Europe, 1880–1945. Social Science Quarterly, 88(2), 494–514.

Kristov, L., Lindert, P. H., & McClelland, R. (1992). Pressure groups and redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 48(2), 135–163.

Kock, H.-J. W. (1984). A constitutional history of Germany in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. London and New York: Longman.

Lampe, M., & Sharp, P. (2012). Tariffs and income: a time series analysis for 24 countries. Cliometrica. doi:10.1007/s11698-012-0088-5.

Lindert, P. H. (1994). The rise in social spending 1880–1930. Explorations in Economic History, 31(1), 1–37.

Lindert, P. H. (2004a). Growing public. Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. Vol. I: The story. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lindert, P. H. (2004b). Growing public. Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. Vol. II: Further evidence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lopez-Cordova, J. E., & Meissner, C. M. (2008). The globalization of trade and democracy, 1870–2000. World Politics, 60(4), 539–575.

Lott, J. R., & Kenny, L. W. (1999). Did women’s suffrage change the size and scope of government? Journal of Political Economy, 107(6), 1163–1198.

Marshall, M., & Jaggers, K. (2011). Polity IV project. Data set users’ manual. Maryland: University of Maryland, Center for International Development and Conflict Management. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4manualv2010.pdf.

Maddison, A. (2003). The world economy: historical statistics. Paris: OECD.

Meissner, C. M. (2005). A new world order: explaining the international diffusion of the gold standard, 1870–1913. Journal of International Economics, 66(2), 385–406.

Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927.

Mitchell, B. R. (2003). International historical statistics: Europe, 1750–2000 (5th ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mueller, D., & Stratmann, T. (2003). The economic effects of democratic participation. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9–10), 2129–2155.

Mulligan, C., Gil, R., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2004). Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 51–74.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426.

Peacock, A. T., & Wiseman, J. (1961). The growth in public expenditures in the United Kingdom. London: Allen & Unwin.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Plumper, T., & Martin, C. W. (2003). Democracy, government spending, and economic growth: a political-economic explanation of the Barro-effect. Public Choice, 117(1–2), 27–50.

Profeta, P., Puglisi, R., & Scabrosetti, S. (2010). Does democracy affect taxation and government spending? Evidence from developing countries (Working Paper No. 149). Center for Research on the Public Sector, Universita Bocconi, Italy.

Przeworski, A. (2009). Conquered or granted? A history of suffrage extensions. British Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 291–321.

Rodrik, D. (1998). Why do more open economies have bigger governments? Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 997–1032.

Sabine, B. E. F. (1966). A history of income tax. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Singer, J. D., & Small, M. (1994). Correlates of war project: international and civil war data, 1816–1992. Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Stokes, S. (2005). Perverse accountability: a formal model of machine politics with evidence from Argentina. The American Political Science Review, 99(3), 315–325.

Stokes, S. (2011). What killed vote buying in Britain? (Unpublished Working Paper). Yale University, Connecticut.

Tanzi, V., & Schuknecht, L. (2000). Public spending in the 20th century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, C. (2004). Contention and democracy in Europe, 1650–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tridimas, G., & Winer, S. L. (2005). The political economy of government size. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(3), 643–666.

Vreeland, J. R. (2008). The effect of political regime on civil war. Unpacking anocracy. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52(3), 401–425.

Wagner, A. (1883). Grundlegung der politischen Oekonomie (3rd ed.). Leipzig: C.F. Winter.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pierre-Guillaume Méon, other participants in the workshop at the University of Aarhus in September 2012, the editor in chief, and three reviewers for helpful suggestions. We also thank Chris Meissner, Markus Lampe and Paul Sharp for sharing data with us. Finally, we thank Lene Holbæk for editorial assistance. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aidt, T.S., Jensen, P.S. Democratization and the size of government: evidence from the long 19th century. Public Choice 157, 511–542 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0073-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0073-y