Abstract

This paper describes the influence of government ideology on economic policy-making in the United States. I review studies using data for the national, state and local levels and elaborate on checks and balances, especially divided government, measurement of government ideology and empirical strategies to identify causal effects. Many studies conclude that parties do matter in the United States. Democratic presidents generate, for example, higher rates of economic growth than Republican presidents, but these studies using data for the national level do not identify causal effects. Ideology-induced policies are prevalent at the state level: Democratic governors implement somewhat more expansionary and liberal policies than Republican governors. At the local level, government ideology hardly influences economic policy-making at all. How growing political polarization and demographic change will influence the effects of government ideology on economic policy-making will be an important issue for future research.

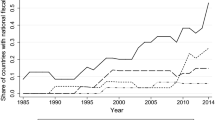

Source: Beland and Oloomi (2017)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

By using Gallup survey data collected over the period July 2015 to August 2016, Rothwell (2016) shows that variables such as racial isolation help to predict views of Trump, but not of other Republican presidential candidates. On the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, see Kurrild-Klitgaard (2017).

Germany is a case in point. Government ideology did not predict economic policies at the national level over the 1950–2015 period. Leftwing governments implemented, however, more expansionary policies than rightwing governments in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., De Haan and Zelhorst 1993; Belke 2000; Potrafke 2012; Kauder and Potrafke 2016). Commentators believed that globalization restricted partisan politics in industrialized countries, but there is hardly any evidence for that view (Potrafke 2009). New studies find evidence for ideology-induced effects in European Union countries (Jäger 2017).

For surveys of empirical studies see, for example, Schmidt (1996) and Potrafke (2017). On election-motivated politicians and political business cycles, see the surveys of De Haan and Klomp (2013) and Dubois (2016). Scholars also examine how the political ideology of the median voter is related to policy outcomes such as social expenditures (Congleton and Bose 2010; Congleton et al. 2017).

Other studies—which I do not discuss in more detail—elaborate on partisan politics and political alignment between ideology-induced politicians across the federal, state and local levels (e.g., Levitt and Snyder 1995; Krause and Bowman 2005; Ansolabehere and Snyder 2006; Larcinese et al. 2006; Berry et al. 2010; Albouy 2013; Young and Sobel 2013; Goetzke et al. 2017; Hankins et al. 2017).

Kane (2017) maintains that the presidential growth gap becomes smaller when different lags of the government ideology variables are entered.

Grier (2008) attempts to address the endogeneity concern of the Democratic president variable by creating a 12-observation sample to predict whether the Democratic candidate will win the election (the 1961–2004 period includes 12 presidential elections). The predicted probability is then used as an instrument for the Democratic president variable in the GDP regressions.

See also Snowberg et al. (2007b).

Some studies exploit cross-sectional variation across US states to examine ideology-induced effects: Monogan (2013) and Soss et al. (2001) include government ideology as an independent variable to explain immigrant policies and welfare policies. Garand (1988) uses univariate time series analysis for the 50 states over the 1945–1984 period and concludes that government ideology overall did not influence the size of government in the US sates.

The first study to employ RDD at the state level is Leigh (2008). The threshold of narrow majorities for governor’s elections is, however, quite all-encompassing: the author excludes elections in which one party won 80% or more of the vote and in which one of the two top candidates was an independent. The dummy variable for Democrat governors does not turn out to be statistically significant for 26 of the 32 dependent variables he studies. The results show that minimum wages, post-tax incomes and welfare caseloads were higher, but that incarceration rates, post-tax inequality and unemployment rates were lower under Democrat than under Republican governors.

Ferreira and Gyourko (2014) also examine how the gender of the mayors influences policies.

The vote share for Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential elections was correlated with city spending (Einstein and Kogan 2016). For example, city spending on police, fire, public transit and parks and recreation was higher in places in which the 2008 Democratic presidential vote share was large.

Einstein and Glick (2016) interviewed 72 American mayors asking for their preferences regarding income redistribution. The results suggest that Democratic mayors are more inclined towards income redistribution than Republican mayors. The sample includes, for example, 16 of the 46 mayors of cities with more than 400,000 inhabitants in the United States.

References

Abrams, B. A., & Iossifov, P. (2006). Does the Fed contribute to a political business cycle? Public Choice, 129, 249–262.

Adams, J., & Merrill, S. (2008). Candidates and party strategies in two-stage elections beginning with a primary. American Journal of Political Science, 52, 344–359.

Agrawal, D., Fox, W. F., & Slemrod, J. (2015). Competition and sub-national governments: Tax competition, competition in urban areas and education competition. National Tax Journal, 68, 701–734.

Albouy, D. (2011). Do voters affect or elect policies? A new perspective, with evidence from the U.S. Senate. Electoral Studies, 30, 162–173.

Albouy, D. (2013). Partisan representation in Congress and the geographic distribution of federal funds. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 127–141.

Alesina, A. (1987). Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 651–678.

Alesina, A., & Rosenthal, H. (1995). Partisan politics, divided government, and the economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alesina, A., & Rosenthal, H. (1996). A theory of divided government. Econometrica, 64, 1311–1341.

Alesina, A., Roubini, N., & Cohen, G. D. (1997). Political cycles and the macroeconomy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Alesina, A., & Sachs, J. (1988). Political parties and the business cycle in the United States, 1948–1984. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 20, 63–82.

Alm, J., & Rogers, J. (2011). Do state fiscal policies affect state economic growth? Public Finance Review, 39, 483–526.

Alt, J. E., Lassen, D. D., & Skilling, D. (2002). Fiscal transparency, gubernatorial approval, and the scale of government: Evidence from the states. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 2, 230–250.

Alt, J. E., & Lowry, R. C. (1994). Divided government, fiscal institutions, and budget deficits: Evidence from the states. American Political Science Review, 88, 811–828.

Alt, J. E., & Lowry, R. C. (2000). A dynamic model of state budget outcomes under divided partisan government. Journal of Politics, 62, 1035–1069.

Alt, J. E., & Rose, S. S. (2009). Context-conditional political budget cycles. In C. Boix & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics (pp. 845–867). Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Andersen, A. L., Lassen, D. D., & Nielsen, L. H. W. (2012). Late budgets. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4, 1–40.

Ansolabehere, S., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2006). Party control of state government and the distribution of public expenditures. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 108, 547–569.

Ash, E. (2015). The political economy of tax laws in the U.S. states. Mimeo.

Atkinson, A. B., Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2011). Top incomes in the long run of history. Journal of Economic Literature, 49, 3–71.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Majlesi, K. (2016). Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. NBER Working Paper No. 22637.

Bartels, L. M. (2016). Unequal democracy (2nd ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Beland, L.-P. (2015). Political parties and labor market outcomes: Evidence from U.S. states. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7, 198–220.

Beland, L.-P., & Boucher, V. (2015). Polluting politics. Economics Letters, 137, 176–181.

Beland, L.-P., Eren, O., & Unel, B. (2015). Politics and entrepreneurial activity in the U.S. LSU Working Paper.

Beland, L.-P., & Oloomi, S. (2017). Party affiliation and public spending: Evidence from U.S. governors. Economic Inquiry, 55, 982–995.

Beland, L.-P., & Unel, B. (2015). The impact of party affiliation of U.S. governors on immigrants’ labor market outcomes. LSU Working Paper.

Beland, L.-P., & Unel, B. (2017). Governors’ party affiliation and unions. Industrial Relations, forthcoming.

Belke, A. (1996). Politische Konjunkturzyklen in Theorie und Empirie: Eine kritische Analyse der Zeitreihendynamik in Partisan-Ansätzen. Tübingen: Mohr.

Belke, A. (2000). Partisan political business cycles in the German labour market? Empirical tests in the light of the Lucas-critique. Public Choice, 104, 225–283.

Bergh, A., & Bjørnskov, C. (2017). Trust us to repay: Social trust, long-term interest rates, and sovereign credit ratings. Mimeo.

Bernecker, A. (2016). Divided we reform: Evidence from U.S. welfare policies. Journal of Public Economics, 142, 24–38.

Berry, C. R., Burden, B. C., & Howell, W. G. (2010). The president and the distribution of federal spending. American Political Science Review, 104, 783–799.

Berry, W. D., Ringquist, E. J., Fording, R. C., & Hanson, R. L. (1998). Measuring citizen and government ideology in the American States, 1960–1993. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 327–348.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (1995). Does electoral accountability affect economic policy choices? Evidence from gubernatorial term limits. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 769–798.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2003). Political institutions and policy choices: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 7–73.

Besley, T., Persson, T., & Sturm, D. M. (2010). Political competition, policy and growth: Theory and evidence from the US. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1329–1352.

Bjørnskov, C., & Potrafke, N. (2013). The size and scope of government in the US states: Does party ideology matter? International Tax and Public Finance, 20, 687–714.

Blinder, A. S., & Watson, M. W. (2016). Presidents and the US economy: An econometric exploration. American Economic Review, 106, 1015–1045.

Blomberg, S. B., & Hess, G. D. (2003). Is the political business cycle for real? Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1091–1121.

Bonica, A. (2014). Mapping the ideological marketplace. American Journal of Political Science, 58, 367–387.

Broz, J. L. (2008). Congressional voting on funding the international financial institutions. Review of International Organizations, 3, 351–374.

Broz, J. L. (2011). The United States Congress and IMF financing, 1944–2009. Review of International Organizations, 6, 341–368.

Cahan, D. (2017). Electoral cycles in government employment: Evidence from US gubernatorial elections. UCSD Working Paper.

Cahan, D., & Potrafke, N. (2017). The Democratic-Republican presidential growth gap and the partisan balance of the state governments. CESifo Working Paper No. 6517.

Calcagno, P. T., & Escaleras, M. (2007). Party alternation, divided government, and fiscal performance within US states. Economics of Governance, 8, 111–128.

Calcagno, P. T., & Lopez, E. J. (2012). Divided we vote. Public Choice, 151, 517–536.

Caplan, B. (2001). Has Leviathan been bound? A theory of imperfectly constrained government with evidence from the states. Southern Economic Journal, 67, 825–847.

Caporale, T., & Grier, K. B. (2000). Political regime change and the real interest rate. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 32, 320–334.

Caporale, T., & Grier, K. B. (2005). Inflation, presidents, Fed chairs, and regime shifts in the real interest rate. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 37, 1153–1163.

Caughey, D., Warshaw, C., & Xu, Y. (2017). Incremental democracy: The policy effects of partisan control of state government. Journal of Politics, forthcoming.

Chang, K. H. (2001). The president versus the Senate: Appointments in the American system of separated powers and the Federal Reserve. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 17, 319–355.

Chang, C.-P., Kim, Y., & Ying, Y.-H. (2009). Economics and politics in the United States: A state-level investigation. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 12, 343–354.

Chappell, H. W., Jr., Havrilesky, T. M., & McGregor, R. R. (1993). Partisan monetary policies: Presidential influence through the power of appointment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 185–218.

Chappell, H. W., Jr., & Keech, W. R. (1986). Party differences in macroeconomic policies and outcomes. American Economic Review, 76, 71–74.

Chen, J., & Rodden, J. (2013). Unintentioanal gerrymandering: Political geography and electoral bias in legislatures. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 8, 239–269.

Chen, S.-S., & Wang, C.-C. (2013). Do politics cause regime shifts in monetary policy? Contemporary Economic Policy, 32, 492–502.

Chopin, M., Cole, S., & Ellis, M. (1996a). Congressional influence on U.S. Monetary policy—A reconsideration of the evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 38, 561–570.

Chopin, M., Cole, S., & Ellis, M. (1996b). Congressional policy preferences and U.S. monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 38, 581–585.

Congleton, R. D., Battini, A., & Pietratonio, R. (2017). The electoral politics and the evolution of complex healthcare systems. Kyklos, 70, 483–510.

Congleton, R. D., & Bose, F. (2010). The rise of the modern welfare state, ideology, institutions and income security: Analysis and evidence. Public Choice, 144, 535–555.

De Benedcitis-Kessner, J., & Warshaw, C. (2016). Mayoral partisanship and municipal fiscal policy. Journal of Politics, 78, 1124–1138.

De Haan, J., & Klomp, J. (2013). Conditional political budget cycles: A review of recent evidence. Public Choice, 157, 387–410.

De Haan, J., & Zelhorst, D. (1993). Positive theories of public debt: Some evidence for Germany. In H. A. A. Verbon & F. A. A. M. van Winden (Eds.), The political economy of government debt (pp. 295–306). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

De Magalhaes, L. M., & Ferrero. L. (2011). Political parties and the tax level in the American states: A regression discontinuity design. University of Bristol, Economics Department Discussion Paper No 10/614.

De Magalhaes, L. M., & Ferrero, L. (2014). Separation of powers and the tax level in the U.S. states. Southern Economic Journal, 82, 598–619.

Dilger, R. (1998). Does politics matter? Partisanship’s impact on state spending and taxes, 1985–1995. State and Local Government Review, 30, 139–144.

Downey, M. (2017). Losers go to jail: Congressional elections and union officer prosecutions. UCSD Working Paper.

Drometer, M., & Meango, R. (2017). Electoral cycles, partisan effects and U.S. naturalization policies. Ifo Working Paper No. 239.

Dubois, E. (2016). Political business cycles 40 years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, 166, 235–259.

Eichler, S., & Lähner, T. (2017). Regional, individual and political determinants of FOMC members’ key macroeconomic forecasts. International Journal of Forecasting, forthcoming.

Einstein, K. L., & Glick, D. M. (2016). Mayors, partisanship, and redistribution: Evidence directly from U.S. mayors. Mimeo.

Einstein, K. L., & Kogan, V. (2016). Pushing the city limits: Policy responsiveness in municipal government. Urban Affairs Review, 52, 3–32.

Erler, H. A. (2007). Legislative term limits and state spending. Public Choice, 133, 479–494.

Escaleras, M., & Calcagno, P. T. (2007). Does the gubernatorial term limit type affect state government expenditures? Public Finance Review, 37, 572–595.

Falk, N., & Shelton, C. A. (2017). Fleeing a lame duck: Policy uncertainty and manufactory investment in U.S. states. Mimeo.

Faust, J., & Irons, J. S. (1999). Money, politics and the post-war business cycle. Journal of Monetary Economics, 43, 61–89.

Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2009). Do political parties matter? Evidence from U.S. cities. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 399–422.

Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2014). Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors? Journal of Public Economics, 112, 24–39.

Flores-Macías, G. A., & Kreps, S. E. (2013). Political parties at war: A study of American war finance, 1789–2010. American Political Science Review, 107, 833–848.

Fredriksson, P. G., & Wang, L. (2011). Sex and environmental policy in the U.S. House of Representative. Economics Letters, 113, 228–230.

Fredriksson, P. G., Wang, L., & Mamun, K. A. (2011). Party politics, governors, and economic policy. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 62, 241–253.

Fredriksson, P. G., Wang, L., & Warren, P. L. (2013). Party politics, governors, and economic policy. Southern Economic Journal, 80, 106–126.

Frey, B. S., & Schneider, F. G. (1978a). An empirical study of politico-economic interaction in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics, 60, 174–183.

Frey, B. S., & Schneider, F. G. (1978b). A politico-economic model of the United Kingdom. Economic Journal, 88, 243–253.

Garand, J. C. (1988). Explaining government growth in the U.S. states. American Political Science Review, 82, 837–849.

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. M., & Taddy, M. (2016). Measuring polarization in high-dimensional data: Method and application to congressional speech. Working paper.

Gerber, E. R. (2013). Partisanship and local climate policy. Cityscape, 15, 107–124.

Gerber, E. R., & Hopkins, D. J. (2011). When mayors matter: Estimating the impact of mayoral partisanship on city policy. American Journal of Political Science, 55, 326–339.

Gilligan, T. W., & Matsusaka, J. G. (1995). Deviations from constituent interests: The role of legislative structure and political parties in the states. Economic Inquiry, 33, 383–401.

Goetzke, F., Hankins, W., & Hoover, G. (2017). Partisan determinants of federal highway grants. CESifo Working Paper No. 6603.

Gray, V. D., Lowery, D., Monogan, J., & Godwin, E. K. (2010). Incrementing toward nowhere: Universal healthcare coverage in the states. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 40, 82–113.

Grier, K. B. (1991). Congressional influence on U.S. monetary policy—An empirical test. Journal of Monetary Economics, 28, 201–220.

Grier, K. B. (1996). Congressional oversight committee influence on U.S. monetary policy revisited. Journal of Monetary Economics, 38, 571–579.

Grier, K. B. (2008). US presidential elections and real GDP growth, 1961–2004. Public Choice, 135, 337–352.

Grogan, C. M. (1994). Political-economic factors influencing state Medicaid policy. Political Research Quarterly, 47, 589–623.

Gu, J., Compton, R. A., Giedeman, D. C., & Hoover, G. (2017). A note on economic freedom and political ideology. Applied Economics Letters, 24, 928–931.

Hajnal, Z. J., & Horowitz, J. D. (2014). Racial winners and losers in American party politics. Perspectives on Politics, 12, 100–118.

Hankins, W., Hoover, C., & Pecorino, P. (2017). Party polarization, political alignment, and federal grant spending at the state level. Economics of Governance, 18, 351–389.

Havrilesky, T. (1987). A partisanship theory of fiscal and monetary regimes. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 19, 308–325.

Havrilesky, T. (1988). Monetary policy signalling from administration to the Federal Reserve. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 20, 83–99.

Havrilesky, T. (1991). The frequency of monetary policy signalling from administration to the Federal Reserve: Note. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 23, 423–428.

Havrilesky, T., & Gildea, J. (1992). Reliable and unreliable partisan appointees to the Board of Governors. Public Choice, 73, 397–417.

Haynes, S. E., & Stone, J. A. (1990). Political models of the business cycle should be revived. Economic Inquiry, 28, 442–465.

Hess, G., & Shelton, C. A. (2016). Congress and the Federal Reserve. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48, 603–633.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review, 71, 1467–1487.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr. (1986). Political parties and macroeconomic policies and outcomes in the United States. American Economic Review, 76, 66–70.

Hibbs, D. A., Jr. (1987). The American political economy: Macroeconomics and electoral politics. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Hill, A., & Jones, D. B. (2017). Does partisan affiliation impact the distribution of spending? Evidence from state governments’ expenditures of education. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 143, 58–77.

Innes, R., & Mitra, A. (2015). Parties, politics and regulation: Evidence from clean air act enforcement. Economic Inquiry, 53, 522–539.

Jacobson, G. C. (2012). The electoral origins of polarized politics: Evidence from the 2010 cooperative congressional election study. American Behavioral Scientist, 56, 1612–1630.

Jacobson, G. C. (2016a). Polarization, gridlock, and presidential campaign politics in 2016. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667, 226–246.

Jacobson, G. C. (2016b). The Obama legacy and the future of partisan conflict: Demographic change and generational imprinting. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667, 72–91.

Jacobson, G. C., & Carson, J. L. (2016). The politics of congressional elections (9th ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Jäger, K. (2017). Economic freedom in the early 21st century: Government ideology still matters. Kyklos, 70, 256–277.

Joshi, N. K. (2015). Party politics, governors, and healthcare expenditures. Economics and Politics, 27, 53–77.

Kane, T. (2017). Presidents and the US economy: Comment. Working Paper, Hoover Institution, Stanford.

Kauder, B., & Potrafke, N. (2016). The growth in military expenditure in Germany 1950–2011: Did parties matter? Defense and Peace Economics, 27, 503–519.

Keita, S., & Mandon, P. (2017). Give a fish or teach fishing? Political affiliation of U.S. governors and the poverty status of immigrants. European Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Klarner, C. E., Phillips, J. H., & Muckler, M. (2012). Overcoming fiscal gridlock: Institutions and budget bargaining. Journal of Politics, 74, 992–1009.

Knight, B. G. (2000). Supermajority voting requirements for tax increases: Evidence from the states. Journal of Public Economics, 76, 41–67.

Kousser, T. (2002). The politics of discretionary Medicaid spending, 1980–1993. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 27, 639–671.

Krause, G. A. (2005). Electoral incentives, political business cycles and macroeconomic performance: Empirical evidence from post-war US personal income growth. British Journal of Political Science, 35, 77–101.

Krause, G. A., & Bowman, A. (2005). Adverse selection, political parties, and policy delegation in the American federal system. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 21, 359–387.

Kurrild-Klitgaard, P. (2017). Trump, Condorcet, and Borda: Voting paradoxes in the 2016 Republican presidential primaries. European Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Langer, L., & Brace, P. (2005). The preemptive power of state supreme courts: Adoption of abortion and death penalty legislation. Policy Studies Journal, 33, 317–340.

Larcinese, V., Rizzo, L., & Testa, C. (2006). Allocating the U.S. federal budget to the states: The impact of the president. Journal of Politics, 68, 446–457.

Lee, D. S. (2008). Randomized experiments from non-random selection in U.S. House elections. Journal of Econometrics, 142, 675–697.

Lee, D. S., & Lemieux, T. (2010). Regression discontinuity designs in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 48, 281–355.

Lee, D. S., Moretti, E., & Butler, M. J. (2004). Do voters affect or elect policies? Evidence from the U.S. House. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 807–859.

Leigh, A. (2008). Estimating the impact of partisanship on policy settings and economic outcomes: A regression discontinuity approach. European Journal of Political Economy, 24, 256–268.

Levitt, S., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (1995). Political parties and the distribution of federal outlays. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 958–980.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2013). The VP-function revisited: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after over 40 years. Public Choice, 157, 367–385.

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McGregor, R. R. (1996). FOMC voting behavior and electoral cycles: Partisan ideology and partisan loyalty. Economics and Politics, 8, 17–32.

Monogan, J. E. (2013). The politics of immigrant policy in the 50 states, 2005–2011. Journal of Public Policy, 33, 35–64.

Nannestad, P., & Paldam, M. (1994). The VP-function: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after 25 years. Public Choice, 79, 213–245.

Neumeier, F. (2015). Do businessmen make good governors? MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series No 19-2015.

Pastor, L., & Veronesi, P. (2017). Political cycles and stock returns. Chicago Booth Paper No. 17-01.

Pickering, A. C., & Rockey, J. (2013). Ideology and the size of US state government. Public Choice, 156, 443–465.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (1985). A spatial model of legislative roll call analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 29, 357–384.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2007). Ideology and Congress. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Portmann, M., Stadelmann, D., & Eichenberger, R. (2012). District magnitude and representation of the majority’s preferences: Evidence from popular and parliamentary votes. Public Choice, 151, 585–610.

Poterba, J. M. (1994). States responses to fiscal crises: The effects of budgetary institutions and politics. Journal of Political Economy, 102, 799–821.

Potrafke, N. (2009). Did globalization restrict partisan politics? An empirical evaluation of social expenditures in a panel of OECD countries. Public Choice, 140, 105–124.

Potrafke, N. (2012). Is German domestic social policy politically controversial? Public Choice, 153, 393–418.

Potrafke, N. (2013). Evidence on the political principal–agent problem from voting on public finance for concert halls. Constitutional Political Economy, 24, 215–238.

Potrafke, N. (2017). Partisan politics: Empirical evidence from OECD panel studies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45, 712–750.

Primo, D. M. (2006). Stop us before we spend again: Institutional constraints on government spending. Economics and Politics, 18, 269–312.

Quinn, D. P., & Shapiro, R. Y. (1991). Economic growth strategies: The effects of ideological partisanship on interest rates and business taxation in the United States. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 656–685.

Reed, W. R. (2006). Democrats, republicans, and taxes: Evidence that political parties matter. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 725–750.

Rogers, D. L., & Rogers, J. H. (2000). Political competition and state government size: Do tighter elections produce looser budgets? Public Choice, 105, 1–21.

Rose, S. (2006). Do fiscal rules dampen the political business cycle? Public Choice, 128, 407–431.

Rothwell, J. (2016). Explaining nationalist political views: The case of Donald Trump. Mimeo.

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2016). Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from capitalized income tax data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131, 519–578.

Santa-Clara, P., & Valkanov, R. (2003). The presidential puzzle: Political cycles and the stock market. Journal of Finance, 58, 1841–1872.

Schinke, C. (2014). Government ideology, globalization, and top income shares in OECD countries. Ifo Working Paper No. 181.

Schmidt, M. G. (1996). When parties matter: A review of the possibilities and limits of partisan influence on public policy. European Journal of Political Research, 30, 155–186.

Schnakenberg, K. E., Turner, I. R., & Uribe-McGuire, A. (2017). Allies or commitment devices? A model of appointments to the Federal Reserve. Economics and Politics, 29, 118–132.

Shipan, C. R., & Volden, C. (2006). Bottom-up federalism: The diffusion of antismoking policies from U.S. cities to states. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 825–843.

Shor, B., & McCarty, N. (2011). The ideological mapping of American legislatures. American Political Science Review, 105, 530–551.

Smales, L. A., & Apergis, N. (2016). The influence of FOMC member characteristics on the monetary policy decision-making process. Journal of Banking & Finance, 64, 216–231.

Snowberg, E., Wolfers, J., & Zitzewitz, E. (2007a). Partisan impacts on the economy: Evidence from prediction markets and close elections. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122, 807–829.

Snowberg, E., Wolfers, J., & Zitzewitz, E. (2007b). Party influence in Congress and the economy. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2, 277–286.

Snowberg, E., Wolfers, J., & Zitzewitz, E. (2011). How prediction markets can save event studies. In L. V. Williams (Ed.), Prediction markets (pp. 18–34). London: Routledge.

Soss, J., Schram, S. F., Vartanian, T. P., & O’Brien, E. (2001). Setting the terms of relief: Explaining state policy choices in the devolution revolution. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 378–395.

Verstyuk, S. (2004). Partisan differences in economic outcomes and corresponding voting behaviour: Evidence from the U.S. Public Choice, 120, 169–189.

Winters, R. (1976). Party control and policy change. American Journal of Political Science, 20, 597–636.

Young, A. T., & Sobel, R. S. (2013). Recovery and Reinvestment Act spending at the state level: Keynesian stimulus or distributive politics? Public Choice, 155, 449–468.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for comments from David Agrawal, Larry Bartels, Louis-Phillippe Beland, Christian Bjørnskov, Dodge Cahan, Devin Caughey, Leandro De Magalhaes, Axel Dreher, Per Fredriksson, Stefanie Gäbler, Roger Gordon, James Hamilton, Gary Jacobson, Björn Kauder, Pierre Mandon, Florian Neumeier, Lubos Pastor, Andrew Pickering, James Rockey, Christoph Schinke, Cameron Shelton, William F. Shughart II, Erik Snowberg, Heinrich Ursprung, and two anonymous referees, Christopher Costea, Kristin Fischer and Alexander van Roessel for excellent research assistance, and Lisa Giani-Contini for proof-reading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Potrafke, N. Government ideology and economic policy-making in the United States—a survey. Public Choice 174, 145–207 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0491-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0491-3

Keywords

- Government ideology

- Economic policy-making

- Partisan politics

- United States

- Democrats

- Republicans

- Political polarization

- Causal effects