Abstract

We model a two-party electoral game with rationally inattentive voters. Parties are endowed with different administrative competencies and announce a fiscal platform to be credibly implemented in case of electoral success. The budgetary impact of each platform depends on the party’s competence and on a stochastic implementation shock. Voters rely on the announced platform to infer a party’s unobserved competence. In addition, voters receive noisy signals on the impact of each fiscal platform with noise depending ultimately on a voter’s cognitive skills. We predict that the interplay between the desire of parties to win the election (the incentive to manipulate voters’ beliefs) and voters’ (lack of) cognitive skills (the scope for manipulation) distorts fiscal policies towards excessive budget deficits. The mechanism is that parties attempt to manipulate inferences on their competencies by implementing a loose fiscal policy. The predictions are tested empirically on a sample of advanced economies over years 1999–2008. Our results remain stable after controlling for potentially confounding differences across countries and over time, along with unobserved heterogeneity. Finally, alternative mechanisms potentially driving our results are investigated and ruled out.

Source: World Bank)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the manipulation literature (Rogoff and Siebert, 1988, for instance), excessive public expenditure or excessively low taxation are used to induce uninformed voters to overestimate parties’ administrative abilities. Manipulation of imperfectly informed voters, however, does not represent the unique explanation for excessive budget deficits. Alternative mechanisms are based on common resources externalities (see Weingast et al., 1981) and on rent extraction. Rents may come from financing preferred public goods (Alesina and Tabellini, 1990) or in transferring resources to preferred groups (Battaglini and Coate 2008). For a recent survey of those different mechanisms, see Yared (2019).

In principle, voters’ beliefs are less likely be manipulated when voters can access more sources of transparent information freely (Alt and Lassen, 2006; Shi and Svensson, 2006). However, even if many high-quality sources are available at no out-of-pocket expense, information remains costly owing to the time necessary to interpret and process its content.

The assumption of binding electoral announcements is pervasive in the literature (see, for instance, Schultz, 1996; Persson and Tabellini, 1999; Martin and Stevenson, 2001; Bellettini and Roberti, 2020). Two contributions, Alesina (1988) and Aragones et al. (2007), have rationalized the assumption by looking at reputational mechanisms. Other studies have argued that the announcements also influence the formation of coalitions and the selection of policies (Austen-Smith and Banks, 1988; Bandyopadhyay and Chatterjee, 2006; Debus, 2009).

Think, for instance, of the risk premium demanded by lenders, the chance of a debt crisis and the macroeconomic costs following abrupt fiscal consolidation. The quadratic form implies a loss of welfare even if the current budget balance is larger than T. In equilibrium, however, that case is ruled out.

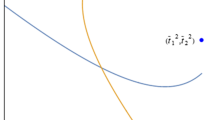

In Fig. 1a and 1b, the values assigned to \(\sigma_{x}^{2}\) entail substantial uncertainty about the budgetary effects of fiscal platforms. Under full information (\(\lambda\) = 1) and with T = 0, the variance \(\sigma_{x}^{2} = 0.1\) (\(\sigma_{x}^{2} = 0.2) \) implies that the balance deviates by more than 20% (30%) from its expected value with a probability larger than 0.5.

The relationship between party polarization and the intensity of political competition also is emphasized in the political science literature. McCarty et al. (2006) link increasing campaign expenditures in US elections to the greater polarization of candidates. It is worth noting that the notion of government polarization is associated neither with the divide between majoritarian and proportional electoral systems nor with voter polarization. Regarding the former, one may have a polarized cabinet within a coalition, and a non-polarized cabinet under a majoritarian system. Hence, our measure of polarization is unlikely to capture the common pool externality that affects fiscal policies under coalition governments. With respect to the latter, an influential political science scholar (Fiorina 1999) enlists voter polarization as only one of seven possible sources of party polarization.

The countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

As explained in the theoretical section, we follow some influential previous literature (Alesina, 1988; Aragones et al., 2007; Martin and Stevenson, 2001; Persson and Tabellini, 1999; Schultz, 1996) and assume binding electoral announcements (for details, see footnote 3). Accordingly, a polarized pre-electoral environment is conducive to an ideologically polarized government; thus, a post-election variable can capture pre-election concerns.

We also rely on two other measures to control for the education level as further robustness checks. Specifically, we consider the education component of the Human Development Index provided by the United Nations (measured as the average of years of schooling of adults and children) and the tertiary education enrollment rate provided by UNESCO. All conclusions hold.

The conclusion follows from the complexities of the public budgets of advanced economies and from the difficulties in assessing the full welfare effects of an expenditure shock (Alesina and Perotti 1996).

For the sake of brevity, results are not shown and are available upon request.

Sampled presidential democracies are France, Switzerland, and the United States. Switzerland is a special case of presidential democracy because the president enjoys no formal powers, and the post rotates every year. Our results hold when excluding France and the United States from and keeping Switzerland in the sample.

In detail: Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The CPI is computed by Transparency International based on perceptions of corruption by businesspeople, risk analysts, and the general public. The index ranges between 10 (highly clean) and 0 (highly corrupt). The 0–10 scale has been adopted from 1995 to 2011. In 2012, Transparency International revised the methodology applied in building the index, also widening its range from 0 to 100. It is worth noting that we rely on the CPI because it is the most widely accepted indicator of corruption worldwide (e.g., Donchev and Ujhelyi 2014; Qu et al., 2019).

It is measured by the probability that two randomly picked government deputies belong to different parties.

Alternatively, we augment the equation with a dummy that equals one in the year before elections and, again, the baseline results remain unchanged.

The same conclusion can be reached with other measures from different sources, such as those described in footnote 9.

It is worth noting that when voter turnout is defined as percentage of the voting-age population, the denominator leaves out those that have not yet reached the age at which one is legally allowed to vote, i.e., 18 years old in most Western countries (see Geys, 2006). This may explain the different sign of the correlation, even being not statistically significant. This is consistent with the above argument that LITERACY captures different voters’ skills than general education, which is usually found to elevate electoral participation.

References

Alesina, A. (1988). Credibility and convergence in a two-party system with rational voters. American Economic Review, 78(4), 796–805.

Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1996). Fiscal discipline and the budget process. American Economic Review, 86(2), 401–407.

Alesina, A., & Tabellini, G. (1990). A positive theory of fiscal deficits and government debts. Review of Economic Studies, 57(3), 403–414.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. D. (2006). Fiscal transparency, political parties, and debt in OECD countries. European Economic Review, 50(6), 1403–1439.

Altonji, J. G., Elder, T. E., & Taber, C. R. (2005). Selection on observed and unobserved variables: Assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools. Journal of Political Economy, 113(1), 151–184.

Aragones, E., Palfrey, T., & Postelwaite, A. (2007). Political reputations and campaign promises. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(4), 846–884.

Ashworth, S., & De Mesquita, E. B. (2014). Is voter competence good for voters? Information, rationality, and democratic performance. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 565–587.

Austen-Smith, D., & Banks, J. (1988). Elections, coalitions and legislative outcomes. American Political Science Review, 82(2), 405–422.

Bandyopadhyay, S., & Chatterjee, K. (2006). Coalition theory and its applications: A survey. Economic Journal, 116(509), F136–F155.

Battaglini, M., & Coate, S. (2008). A dynamic theory of public spending, taxation, and debt. American Economic Review, 98(1), 201–236.

Bellemare, M. F., Takaaki M., & Pepinsky T.B. (2017). Lagged explanatory variables and the estimation of causal effect. The Journal of Politics 79(3).

Bellettini, G., & Roberti, P. (2020). Politicians’ coherence and government debt. Public Choice, 182(1–2), 73–91.

Blais, A. (2000). To vote or not to vote. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bracco, E., Porcelli, F., & Redoano, M. (2019). Political competition, tax salience and accountability. Theory and evidence from Italy. European Journal of Political Economy, 58, 138–163.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2005). Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1271–1295.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2008). How do budget deficits and economic growth affect reelection prospects? Evidence from a large panel of countries. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2203–2200.

Brennan, J. (2012). The ethics of voting. Princeton University Press.

Caplan, B. (2007). The myth of the rational voter. Princeton University Press.

Caplin, A., & Dean, M. (2015). Revealed preference, rational inattention, and costly information acquisition. American Economic Review, 105(7), 2183–2203.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2011). The long-term impacts of teachers: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood (No. w17699). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cukierman, A., Edwards, S., & Tabellini, G. (1992). Seigniorage and political instability. American Economic Review, 82(3), 537–555.

Debus, M. (2009). Pre-electoral commitments and government formation. Public Choice, 138(1–2), 45–64.

Dollery, B. E., & Worthington, A. C. (1996). The empirical analysis of fiscal illusion. Journal of Economic Surveys, 10(3), 261–297.

Donchev, D., & Ujhelyi, G. (2014). What do corruption indices measure? Economics and Politics, 26(2), 309–331.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper & Row.

Drazen, A. (2001). The political business cycle after 25 years. NBER Chapters, 75–138.

Feddersen, T., & Sandroni, A. (2006). A theory of participation in elections. American Economic Review, 96(4), 1271–1282.

Fiorina, M.P. (1999). Whatever happened to the median voter? MIT Conference on Parties and congress, Cambridge, MA.

Fornero, E., & Lo Prete, A. (2019). Voting in the aftermath of a pension reform: The role of financial literacy. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 18(1), 1–30.

Geys, B. (2006). Explaining voter turnout: A review of aggregate-level research. Electoral Studies, 25(4), 637–663.

Goldin, J. (2015). Optimal tax salience. Journal of Public Economics, 131, 115–123.

Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. The Economic Journal, 39, 41–57.

Jappelli, T. (2010). Economic literacy: An international comparison. The Economic Journal, 120(548), F429–F451.

Katsimi, M., & Sarantides, V. (2012). Do elections affect the composition of fiscal policy in developed, established democracies? Public Choice, 151(1), 325–362.

Lane, P. R. (2003). The cyclical behaviour of fiscal policy: Evidence from the OECD. Journal of Public Economics, 87(12), 2661–2675.

Lee, F. E. (2015). How party polarization affects governance. Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 261–282.

Lusardi, A. (2008). Household saving behavior: the role of literacy, information and financial education programs. NBER Working Paper No. 13824.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44.

Mailath, G. (1987). Incentive compatibility in signalling games with a continuum of types. Econometrica, 55(6), 1348–1365.

Martin, L. W., & Stevenson, R. T. (2001). Government formation in parliamentary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 33–50.

Martinelli, C. (2001). Elections with privately informed parties and voters. Public Choice, 108(1–2), 147–167.

Matějka, F., & Tabellini, G. (2020). Electoral competition with rationally inattentive voters. Journal of the European Economic Association. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa042,forthcoming

Mattieß, T. (2020). Retrospective pledge voting: A comparative study of the electoral consequences of government parties’ pledge fulfilment. European Journal of Political Research, 59, 774–796.

Mauro, P., Romeu, R., Binder, A., & Zaman, A. (2015). A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 76, 55–70.

McCarty, N.M., Poole, K.T. & Rosenthal H. (2006). Polarized America: the dance of ideology and unequal riches. The Walras-Pareto Lectures, Cambridge Ma., MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (1999). The size and scope of government: Comparative politics with rational politicians. European Economic Review, 43(4), 699–735.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effect of constitutions: What do the data say? MIT Press.

Qu, G., Slagter, B., Sylwester, K., & Doiron, K. (2019). Explaining the standard errors of corruption perception indices. Journal of Comparative Economics, 47(4), 907–920.

Reed, W. R. (2015). On the practice of lagging variables to avoid simultaneity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 77(6), 897–905.

Rogoff, K. (1990). Equilibrium political budget cycles. American Economic Review, 80, 21–36.

Rogoff, K., & Siebert, A. (1988). Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. The Review of Economic Studies, 55(1), 1–16.

Schmidt, M. G. (1992). Regierungen: Parteipolitische Zusammensetzung. In M. G. Schmidt (Ed.), Lexikon der Politik, Band 3: Die westlichen Länder (pp. 393–400). C.H. Beck.

Schultz, C. (1996). Polarization and inefficient policies. Review of Economic Studies, 63(2), 331–344.

Shi, M., & Svensson, J. (2006). Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why? Journal of Public Economics, 90(8), 1367–1389.

Sims, C. (2003). Implications of rational inattention. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(3), 665–690.

Sørensen, R. J. (2014). Political competition, party polarization, and government performance. Public Choice, 161(3–4), 427–450.

Sutter, M. (2003). The political economy of fiscal policy: An experimental study on the strategic use of deficits. Public Choice, 116(3–4), 313–332.

Wagner, R. E. (1976). Revenue structure, fiscal illusion, and budgetary choice. Public Choice, 45–61.

Weingast, B. R., Shepsle, K. A., & Johnsen, C. (1981). The political economy of benefits and costs: A neoclassical approach to distributive politics. Journal of Political Economy, 89(4), 642–664.

Xu, Y. (2019). Collective decision-making of voters with heterogeneous levels of rationality. Public Choice, 178(1–2), 267–287.

Yared, P. (2019). Rising government debt: Causes and solutions for a decades-old trends. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 115–140.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For helpful comments and fruitful discussion, the authors thank: the Editor-in-Chief and three anonymous referees, Rob Alessie, Kerim P. Arin, Michael Berlemann, Emanuele Bracco, Francesco Caselli, Jakob de Haan, Maria L. Di Tommaso, Christopher Hajzler, Annamaria Lusardi, William L. Megginson, Paolo Onofri, Ugo Panizza, Enrico C. Perotti, Andrea F. Presbitero, Riccardo Puglisi, and Francesco Venturini, as well as the seminar participants at the University of Perugia, University of Groningen, Third UAE Quantitative Research Symposium, XXVIII Conference of the Italian Society of Public Economics, 57th Conference of the Italian Economic Association, and the 2018 European Public Choice Society. A previous version of the paper circulated as “Fiscal policy, government polarization, and the economic literacy of voters” available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract = 2,863,016 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2863016. Responsibility for any errors lies solely with the authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murtinu, S., Piccirilli, G. & Sacchi, A. Rational inattention and politics: how parties use fiscal policies to manipulate voters. Public Choice 190, 365–386 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-021-00940-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-021-00940-8

Keywords

- Rational inattention

- Government polarization

- Asymmetric information

- Voter manipulation

- Cognitive skills

- Fiscal policy