Abstract

We examine whether initial public offering (IPO) firms exercise discretion over an individual accrual account on the balance sheet—the allowance for uncollectible accounts—and an individual accrual account on the income statement—bad debt expense. Our research design exploits a unique disclosure requirement related to these accounts (i.e., the ex post disclosure of write-offs of uncollectible accounts), which enables us to develop refined expectation models. We provide evidence that IPO firms have conservative, not aggressive, allowances in the annual periods adjacent to their stock offerings. In fact, the average IPO firm has an allowance that is over four-times leading write-offs. We also provide evidence that IPO firms record larger, not smaller, bad debt expense and are less likely to record income-increasing bad debt expense than matched non-IPO firms. These results challenge the view that IPO firms understate receivables-related accrual accounts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is not possible to evaluate bad debt expense by examining the ending balance of the allowance alone. This is because bad debt expense is influenced jointly by the beginning balance of the allowance, current period write-offs of uncollectible accounts, and the ending balance of the allowance (McNichols and Wilson 1988).

To understand this point, notice that the allowance at the end of year t is established for receivables that become uncollectible in year t + 1. Thus, write-offs of uncollectible accounts in year t + 1 provide a benchmark to evaluate the adequacy of the allowance at the end of year t. We discuss this benchmark further in Sect. 4.

In addition, we observe some confusion in the accounting literature about which individual accrual accounts TWR actually examine. A number of authors discuss the findings of TWR by stating that TWR provide evidence that IPO firms manage bad debt expense downward. Although TWR do not actually examine bad debt expense, TWR nonetheless state that IPO firms “generally provide for less bad debt expenses relative to their accounts receivable than their matches” (p. 202). Our examination of bad debt expense reveals no evidence that IPO firms understate this account, as TWR contend. Thus, our results also provide evidence that runs counter to a claim made by TWR that is sometimes repeated in the accounting literature.

Most of the analyses in TWR focus on discretionary accruals in the post-IPO annual periods. However, TWR also state that they examine discretionary accruals of 130 IPO firms in the pre-IPO annual period (see footnote 4 of their study). They report that their pre-IPO period accrual results are similar to their post-IPO period results.

Evidence suggests that discretionary accruals estimates may be biased in favor of the hypothesis that IPO firms manage earnings upwards in the post-IPO annual period (Ball and Shivakumar 2008), and related evidence suggests that discretionary accruals estimates may be biased in periods of large events and transactions (Collins and Hribar 2002). Ball and Shivakumar (2008) find no evidence of earnings management by issuers of IPOs in the United Kingdom, and they identify a number of alternative explanations for alleged earnings management by issuers of IPOs in the United States. However, Lo (2008, p. 356) is more cautious about dismissing the total accruals results of TWR.

The decision to select our sample from this period was influenced by the fact that two of the variables needed to conduct our tests (write-offs of uncollectible accounts and bad debt expense) are not available in any commercial database. Starting in 1997, IPO firms were required to file their Form S-1 (i.e., offering prospectus) with the SEC electronically, so write-offs of uncollectible accounts and bad debt expense could be obtained online from the SEC even though these variables continued to be unavailable in any commercial database. To obtain write-offs of uncollectible accounts and bad debt expense prior to 1997, researchers would have to obtain these data items manually from microfiche.

There are several possible reasons why we could not locate a Schedule II. First, if the information contained in Schedule II is immaterial in relation to the financial statements, some firms may believe that disclosure of Schedule II information is unnecessary. Second, some firms may be unknowingly non-compliant. A number of published accounting studies document that firms do not always comply with SEC reporting requirements (e.g., Alford et al. 1994; Schwartz and Soo 1996). Third, some firms may provide the information required in Schedule II elsewhere in their 10-K filings but omit Schedule II to avoid redundancy. At the same time, we acknowledge that our search procedures may not have located a Schedule II even though it may have been provided. While oversights are possible in some instances, it seems to be an unlikely explanation for all of the apparent omissions.

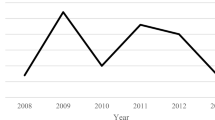

Note that we analyze years −2 through +2 (year 0 is the first annual period following the IPO). Our sample of 444 IPO firms relates to our sample in year 0. For year −2 only, all variables are manually obtained from Schedule II of Form 10-K because Compustat begins coverage with year −1.

All of the variables in Table 2 have been winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the effects of extreme values.

We limit this ratio to a maximum of 0.50 for any given firm, although our inferences and conclusions are unaltered when we impose no limit.

We corroborate these univariate analyses with multivariate regressions, where the allowance is regressed on gross receivables, contemporaneous write-offs, leading write-offs, and an indicator variable for whether the firm is an IPO firm. All of the continuous variables are scaled by net sales. Regressions are estimated in years −2 through +2. The inferences and conclusions from our univariate and multivariate tests are the same.

Analysis of the ratio of the allowance to leading write-offs does not hinge on effective matching because this ratio has meaning independent of comparisons to matched non-IPO firms. However, for completeness, we also analyze this ratio by making comparisons between IPO firms and matched non-IPO firms.

In some instances, firms have meager write-offs but substantial allowances, which yields extremely large mean values for ALLit/WOit+1. We limit the value of ALLit/WOit+1 to a maximum of ten. Also, in some instances, firms have no write-offs but substantial allowances, which yield an undefined value for ALLit/WOit+1. In such instances, we use a value ten for ALLit/WOit+1. Our inferences and conclusions are unaltered when we use a value of five rather than ten.

The analyses in Tables 3 and 4 appear to yield somewhat conflicting results. Notice that ALLit/GARit is significantly smaller for IPO firms than for matched non-IPO firms in the years preceding stock offerings (see Table 3), while ALLit/WOit+1 is indistinguishable between IPO firms and matched non-IPO firms in those same years (see Table 4). One possible explanation for these seemingly conflicting results is that IPO firms are less likely to extend trade credit to risky customers, which would necessitate smaller allowances and yield lower future write-offs. This explanation seems plausible because IPO firms generally have fewer cash resources than matched non-IPO firms. To probe this issue empirically (results not tabulated), we regress year 0 write-offs on (1) year −1 gross receivables, (2) year −1 write-offs, (3) year −1 allowance, (4) an IPO indicator, and (5) interactions between the IPO indicator and each of the other independent variables. The variable of interest in this regression is the interaction between the IPO indicator and year −1 allowance. If our explanation is valid, we should observe a smaller fraction of the year −1 allowance being written-off in year 0 for IPO firms than for matched non-IPO firms. We find that the interaction between the IPO indicator and the year −1 allowance is significantly negative (t-statistic = −3.47, p-value < 0.001), which indicates that a smaller fraction of the allowance is written-off for IPO firms than for matched non-IPO firms.

Bad debt expense is usually income-decreasing, but some firms record income-increasing (or negative) amounts. Because we separately analyze income-increasing bad debt expense, our present analysis of bad debt expense uses values that are winsorized at zero (rather than the 1st percentile) and the 99th percentile.

For parsimony, we specify Eq. 1 in the same manner as McNichols and Wilson (1988). However, in untabulated analyses, we also augment this equation with year indicators, industry indicators (at the two-digit SIC code level), an auditor indicator (using the Big N versus non-Big N dichotomy), operating performance (measured using return on sales), sales growth (measured using percentage growth in sales), accounts receivable turnover, a dot.com indicator (a list of dot.com IPOs was obtained from Jay Ritter’s IPO webpage), and economy-wide bankruptcies (defined as the total number of business bankruptcies in the economy scaled by the total number of corporate tax filers). The addition of these variables does not alter any of our inferences or conclusions.

During the period 1980 through 1990, Schedule II information is only available on microfiche. Over time, some microfiche was apparently lost or misfiled. In addition, some microfiche may not have been initially obtained.

References

Aharony, J., Lin, C., & Loeb, M. (1993). Initial public offerings, accounting choices, and earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 10(1), 61–81.

Alford, A., Jones, J., & Zmijewski, M. (1994). Extensions and violations of the statutory SEC form 10-K filing requirements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17(1/2), 229–254.

Armstrong, C., Foster, G., & Taylor, D. (2008). Earnings management around initial public offerings: A re-examination. Working paper, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Ball, R., & Shivakumar, L. (2008). Earnings quality at initial public offerings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 324–349.

Beneish, D. (2001). Earnings management: A perspective. Managerial Finance, 27(12), 3–17.

Bernard, V., & Skinner, D. (1996). What motivates managers’ choice of discretionary accruals? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 22(1–3), 313–325.

Bhojraj, S., & Libby, R. (2005). Capital market pressure, disclosure frequency-induced earnings/cash flow conflict, and managerial myopia. The Accounting Review, 80(1), 1–20.

Caylor, M. (2009). Strategic revenue recognition to achieve earnings benchmarks. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 29(1), 82–95.

Collins, D., & Hribar, P. (2002). Errors in estimating accruals: Implications for empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 105–134.

DeAngelo, L. (1988). Discussion of evidence of earnings management from the provision for bad debts. Journal of Accounting Research, 26(Suppl), 32–40.

Dechow, P., Sloan, R., & Sweeney, A. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

Dhaliwal, D., Gleason, C., & Mills, L. (2004). Last-chance earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 431–459.

Fan, Q. (2007). Earnings management and ownership retention for initial public offering firms: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review, 82(1), 27–64.

Fields, T., Lys, T., & Vincent, L. (2001). Empirical research on accounting choice. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1–3), 255–307.

Fischer, P., & Stocken, P. (2004). Effect of investor speculation on earnings management. Journal of Accounting Research, 42(5), 843–870.

Friedlan, J. (1994). Accounting choices of issuers of initial public offerings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(1), 1–31.

Guay, W., Kothari, S. P., & Watts, R. (1996). A market-based evaluation of discretionary accrual models. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(3), 83–105.

Healy, P., & Wahlen, J. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383.

Jackson, S., & Liu, X. (2010). The allowance for uncollectible accounts, conservatism, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(3), 565–601.

Johnston, D. (2006). Managing stock option expense: The manipulation of option-pricing model assumptions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(2), 395–425.

Kieso, D., Weygandt, J., & Warfield, T. (2007). Intermediate accounting (12th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A., & Wasley, C. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197.

Lo, K. (2008). Earning management and earnings quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 350–357.

Marquardt, C., & Wiedman, C. (2004). How are earnings managed? An examination of specific accruals. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 461–491.

McNichols, M. (2000). Research design issues in earnings management studies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 19(4–5), 313–345.

McNichols, M., & Wilson, P. (1988). Evidence of earnings management from the provision for bad debts. Journal of Accounting Research, 26(Suppl), 1–31.

Ndubizu, G. (2007). Do cross-border listing firms manage earnings or seize a window of opportunity? The Accounting Review, 82(4), 1009–1030.

Ohlson, J., & Aier, J. (2009). On the analysis of firms’ cash flows. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(4), 1091–1114.

Schwartz, K., & Soo, B. (1996). Evidence of regulatory noncompliance with SEC disclosure rules on auditor changes. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 555–572.

Teoh, S., Wong, T., & Rao, G. (1998a). Are accruals during initial public offerings opportunistic? Review of Accounting Studies, 3(1–2), 175–208.

Teoh, S., Welch, I., & Wong, T. (1998b). Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Finance, 53(6), 1935–1974.

Venkataraman, R., Weber, J., & Willenborg, M. (2008). Litigation risk, audit quality, and audit fees: Evidence from initial public offerings. The Accounting Review, 83(5), 1315–1345.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Richard Sloan (the editor), two anonymous reviewers, Marcus Caylor, Tim Doupnik, Vicki Glackin, Steven Jackson, Leigh Salzsieder, and Rich White for providing insightful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cecchini, M., Jackson, S.B. & Liu, X. Do initial public offering firms manage accruals? Evidence from individual accounts. Rev Account Stud 17, 22–40 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-011-9160-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-011-9160-9