Abstract

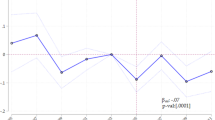

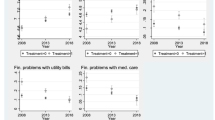

The broad goals of child support policy are to keep children in single-parent families out of poverty and to make sure that their material needs are met. One potentially important, but relatively understudied, set of measures of child well-being are health outcomes. A fixed-effects analysis of data from the Child and Young Adult file of the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth shows that, conditional upon receipt of some amount of child support, higher payment levels are associated with significantly greater odds of having private health insurance coverage and significantly lower odds of poor or declining health status. These effects persist even after controlling for other factors that are likely to be correlated with child support payments, including total family income and paternal visitation patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data collected in 1991 and 1993 are not used because not all health and child support questions were asked in these years. Data from years after 2004 are not used because of the non-representative nature of the very small number of births (to mothers in their 40s with unusually high incomes) in those years.

Throughout the paper, in keeping with most of the literature, I refer to custodial parents or child support recipients (legally, obligees) as mothers and non-resident parents or child support payers (legally, obligors) as fathers. In 2005, 85 % of custodial parents were mothers and 90 % of child support recipients were mothers (U.S. Census Bureau 2007).

For example, Weiss and Willis (1985) argue that more contact will lead to better monitoring of the mother’s expenditures by the father, which will lead to more child support payments. On the other hand, DelBoca and Ribero (2001) present in model in which the father essentially buys contact time from the mother in a world with imperfectly enforceable child support and custody rules.

Estimates for a smaller sample of only children whose fathers were absent in the current interview period produce similar results.

Unlike adult BMI, child BMI is not evaluated on a fixed scale, but rather against the percentile distribution for the child’s age and gender. I have used BMI growth charts produced by the National Center for Health Statistics in 2000 and adopted the definition of the 85th percentile on that chart as the cutoff for overweight and the 10th percentile as the cutoff for underweight.

The variable with the most invalid skips is the parent-reported child health status index. However, there are not any significant differences in observables between children/parents with and without missing values.

When this is broken down, most of the children not at normal body weight are overweight or obese.

References

Aizer, A., & McLanahan, S. (2006). The impact of child support enforcement on fertility, parental investments and child well-being. Journal of Human Resources, 41(1), 28–45.

Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 557–573.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2008). Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. http://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-support/Pages/PeriodicitySchedule.aspx. Accessed 25 sept 2014.

Argys, L. M., & Peters, H. E. (2003). Can adequate child support be legislated? A model of responses to child support and enforcement efforts. Economic Inquiry, 41(3), 463–479.

Argys, L. M., Peters, H. E., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Smith, J. R. (1998). The impact of child support on cognitive outcomes of young children. Demography, 35(2), 159–173.

Becker, G. (1991). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Case, A., Fertig, A., & Paxson, C. (2006). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 365–389.

Case, A., Lubotsky, D., & Paxson, C. (2002). Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. American Economic Review, 92, 1308–1334.

Case, A., & Paxson, C. (2002). Parental behavior and child health. Health Affairs, 21(2), 164–178.

Center for Human Resource Research. (CHRR). The Ohio State University. 2006. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Child and Young Adult Data Users Guide. December.

Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy, and wise: Socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood and human capital development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 47(1), 87–122.

DelBoca, D., & Flinn, C. J. (1994). Expenditure decisions of divorced mothers and income composition. Journal of Human Resources, 61(3), 742–761.

DelBoca, D., & Ribero, R. (2001). The effect of child support policies on visitation and transfers. American Economic Review, 91(2), 130–134.

Garasky, S., & Stewart, S. D. (2007). Evidence of the effectiveness of child support and visitation: Examining food insecurity among children with nonresident fathers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 105–121.

Hofferth, S. L., & Pinzon, A. M. (2011). Do nonresidential fathers’ financial support and contact improve children’s health? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 280–295.

Knox, V. W. (1996). The effects of child support payments on developmental outcomes for elementary school age children. Journal of Human Resources, 31(4), 816–840.

Lerman, R. I. (1993). Child support policies. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(1), 171–182.

Meyer, D., & Hu, M.-C. (1999). A note on the antipoverty effectiveness of child support among mother-only families. Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 225–234.

Morgan, L. W. (2008). Child support guidelines: Interpretation and application. Boston: Wolters Kluwer.

National Center for Health Statistics. (NCHS). (1995). Monthly Vital Statistics Report. No. 43-9. Centers for Disease Control. April.

National Vital Statistics System. (NVSS). (1973). 100 Years of Marriage and Divorce Statistics United States, 1867–1967. DHEW Publication 74-1904.

Nepomnyaschy, L., & Garfinkel, I. (2010). Child support enforcement and fathers’ contributions to their nonmarital children. Social Service Review, 84(3), 341–380.

Peters, H. E., Argys, L. M., Heather Wynder Howard, & Butler, J. S. (2004). Legislating love: The effect of child support and welfare policies on father–child contact. Review of Economics of the Household, 2, 255–274.

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2003). Effects of child health on parents’ relationship status. NBER Working Paper No. 9610.

Seltzer, J. A., Schaeffer, N. C., & Charng, H.-W. (1999). Family ties after divorce: The relationship between visiting and paying child support. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(4), 1013–1032.

Smith, J. P. (2009). The impact of childhood health on adult labor market outcomes. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(3), 478–489.

Taber, J. R. (2012). The effect of health insurance mandates in child support agreements on children’s health insurance coverage. Working Paper, Cornell University.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2007). Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2005. Current Population Report P60-234, August.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). Living arrangements of children under 18 years old: 1960 to present. Historical Table CH-1, January.

Ventura, S. J. (2009). Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States. Data Brief No. 18. National Center for Health Statistics. May.

Weiss, Y., & Willis, R. (1985). Children as collective goods and divorce settlements. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(3), 268–292.

Yeung, W. J., Linver, M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2002). How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development, 73(6), 1861–1879.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baughman, R.A. The impact of child support on child health. Rev Econ Household 15, 69–91 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9268-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-014-9268-3