Abstract

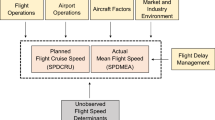

We analyze how schedule times, actual flight times and on-time performance have changed in the U.S. airline industry between 1990 and 2016. We find schedule times have increased in most years, with the largest increases after 2008. Actual flight times and total travel times have also increased but by less than schedule times and the gap has grown over time. This has resulted in reduced arrival delays even though flights are, in fact, taking longer to complete. We discuss the implications of these findings for quality provision and information disclosure within the airline industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regulation 14 CFR Part 234.

Source: ”14 CFR Part 234 Revision of Airline Service Quality Performance Reports and Disclosure Requirements” published by the Department of Transportation in 2007.

Throughout the paper, we will use the terms “arrives” and “arrival time” to refer to the time that a plane arrives at the gate.

Consumers presumably care about how late a flight is compared to its scheduled arrival time (the metric the DOT measures); but they also care about total schedule time. Airlines can improve on the first dimension by deteriorating the second.

It is not clear how consumers value early arrivals. Arriving early allows consumers to make connections and not miss any planned events. However, it often wastes time that could have otherwise been allocated to other activities.

We exclude the first two years of data after the disclosure requirement took effect to avoid any changes in scheduling practices that were an immediate response to the program.

A number of airlines disappear from the data due to mergers. We deal with mergers in the following way. Suppose airline A and airline B merge and maintain the brand of airline B. For routes that were served by airline A but not served by airline B before the merger, we continue to give flights on these routes airline A’s fixed effect after the merger (despite the fact that these flights appear with airline B’s code in the data after the merger). This will ensure that the same flights are compared to each other over time. For routes served by airline B before and after the merger, we use airline B’s fixed effect before and after the merger. For routes that were served by both airlines A and B before the merger, we assign airline B’s code to all of their flights on this route after the merger.

A route is a directional city-pair from a particular origin airport to a particular destination airport.

Total travel time is actual flight time plus departure delay or—put differently—the time between when consumers expected to leave and when they actually arrived.

These measures do not include international flights.

We do not adjust our congestion measures for the number of runways at an airport because our empirical estimation includes route fixed effects. Our results are robust to including squared and cubed terms of the congestion variables and to using dummy variables that indicate the quantiles of the congestion variable at an airport within a year.

For variables that are dummy variables—such as whether or not a flight arrived less than 15 min after its scheduled arrival time—the collapsed variable will measure the fraction of the airline’s flights on the route in the month that arrived less than 15 min after their scheduled arrival time.

Except for the last year which is 2016 instead of 2015.

The online appendix can be found at https://sites.google.com/site/silkeforbes/home/publications

We have also estimated all of our specifications with the use of logged dependent variables, and the results are qualitatively similar.

Departure in the early morning, between 5 am and 10 am, is the omitted group.

The top 30 or 50 airports are determined by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s ”Calendar Year 2016 Preliminary Revenue Enplanements at Commercial Service Airports”.

References

Ater, I., & Orlov, E. (2015). The effect of the internet on performance and quality: Evidence from the airline industry. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97(1), 180–94.

Cao, K. H., Krier, B., Liu, C.-M., McNamara, B., & Sharpe, J. (2017). The nonlinear effects of market structure on service quality: Evidence from the U.S. airline industry. Review of Industrial Organization, 51(1), 43–73.

Dranove, D., & Jin, G. Z. (2010). Quality disclosure and certification: Theory and practice. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(4), 935–963.

Forbes, S. J. (2008). The effect of air traffic delays on airline prices. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26(5), 1218–1232.

Forbes, S. J., Lederman, M., & Tombe, T. (2015). Quality disclosure programs and internal organizational practices: Evidence from airline flight delays. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(2), 1–26.

Forbes, S. J., Lederman, M., & Wither, M. J. (2018). Quality disclosure when firms set their own quality targets. International Journal of Industrial Organization. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2018.04.001

Foreman, S. E., & Shea, D. G. (1999). Publication of information and market response: The case of airline on time performance reports. Review of Industrial Organization, 14(2), 147–162.

Frank, T. (2013). Airlines pad flight schedules to boost on-time records. USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com.

Mayer, C., & Sinai, T. (2003). Why do airlines systematically schedule their flights to arrive late?. The Wharton School:,University of Pennsylvania.

Mazzeo, M. J. (2003). Competition and service quality in the U.S. airline industry. Review of Industrial Organization, 22(4), 275–296.

Mccartney, S. (2010). Why a six-hour flight now takes seven. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com.

Neal, D., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2010). Left behind by design: Proficiency counts and test-based accountability. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2), 263–283.

Prince, J. T., & Simon, D. H. (2014). Do incumbents improve service quality in response to entry? Evidence from airlines’ on-time performance. Management Science, 61(2), 372–390.

Prince, J. T., & Simon, D. H. (2017). The impact of mergers on quality provision: Evidence from the airline industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 65(2), 336–362.

Shumsky, R. (1993). Response of U.S. air carriers to on-time disclosure rule. Transportation Research Record, 1379, 9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forbes, S.J., Lederman, M. & Yuan, Z. Do Airlines Pad Their Schedules?. Rev Ind Organ 54, 61–82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-018-9632-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-018-9632-1