Abstract

China’s higher education system has expanded rapidly since 1999. Exploiting variation in the density of university expansion across provinces and high school cohorts and applying a difference-in-differences model, we estimate the impact of higher education expansion on educational access and attainment with a particular focus on students’ family and demographic backgrounds. Results indicate that the expansion of university spots increased both access and graduation rates at 4-year universities, but this improvement was driven by those of higher social status, including males, those with highly educated fathers, han-ethnic and urban students. Females, rural students and those with low-educated fathers also benefited once they were able to graduate from high school. Also, the policy had only a limited effect on the likelihood of graduating from high school. As in other countries, education expansion in China has not led to equal distribution of educational opportunities, and the least socioeconomically advantaged students are missing out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although little empirical evidence exists regarding the role of higher education in economic growth (Bloom et al. 2014; Gyimah-Brempong et al. 2006; Hanushek 2013, 2016), theoretical analysis has shown that higher education has at least three channels to contribute to economic growth: the accumulation of productive capabilities; the generation of new knowledge from innovation; and the promotion of faster adoption of new technologies (Holmes 2013). See Holmes (2013) and Hanushek (2016) for a brief description of the evolution of economic theories/models on the role of human capital and economic development. Researchers also point out that the quality of education and the efficiency of the institutional environment have an important effect on the capability of higher education to boost economic growth (Pissarides 2000, 2001; Hanushek and Wöβmann 2010). Further, despite the conventional concerns of "brain drain" associated with emigration of highly-skilled workers, research suggests that returned migrants and the linkage between emigrants, returned migrants and home-country workers [facilitate more business opportunities, which in turn contribute to economic growth (Saxenian 2006).

Usually universities plan the allocation of admissions quotas with the Ministry of Education and local governments before they release such information in booklets to students (Yang 2014).

Due to variation in college admissions cut-off scores on the gaokao exam as well as admissions quotas for students from different provinces, students can potentially migrate to regions with lower cut-off scores but higher admissions quotas in order to gain the opportunity to be admitted by the same university. However, regions with lower cut-off scores but higher admissions quotas for local-hukou students tend to be either those in Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjing (i.e. economically developed cities but with high migration restrictions) or the ethnic-minority concentrated remote areas (such as Xinjiang, Tibet, Yunnan etc.). However, central and regional governments normally see such migration as “illegal” and would cancel gaokao migrants’ eligibility for college admission even if the students have valid gaokao scores (Wang and Chan 2005). Further, national statistics do not show a large proportion of such students overall. In addition, we have excluded observations in the ethnic-minority regions and provinces due to differences in college admissions policies for ethnic minority students. Therefore, it is very unlikely that our sample would be biased by having a large number of gaokao migrants.

Even though there is evidence that returns to higher education do not decrease but rather increase in developing countries after massive college expansion (Carnoy et al. 2013a, b), Ou and Zhao (2016) show that there is a wage decrease for college graduates in China who were employed in high-skilled jobs due to the expansion policy. Such a finding might support our observation in this study that students residing in regions with faster expansion in university spots are more likely to be 4-year-college students and graduates. Therefore, the increasing supply of high-skilled workers (as measured by 4-year-university graduates) could lead to more competition in the labor market of college graduates and subsequently lower initial wages as the study by Ou and Zhao (2016) indicates.

Expected year of completion of high school : (1) reported year of completion of middle school + the length of high school study (if no length of high school study was reported, we assume it is 3 years); (2) reported year of completion of primary school + length of middle school study + length of high school study (if no length of middle school study was reported, we assume it is 3 years; same for missing information on high school study length); (3) year of birth + length of primary school study (if no length of primary school study was reported, we assume it is 6 years) + n (n = 6 if month of birth is between January and August; n = 7 if month of birth is between September and December), where n represents years elapsed between birth and starting primary school.

Though this assumption has limitations, we have run several robustness checks to ensure that the results are valid. We ran regressions based on a sample who never changed their hukou registration status from birth and the results qualitatively resemble our main results. We also ran regressions using individuals’ hukou information at the age of 12. The results (available upon request) are also similar to those using the hukou information at birth.

We have also employed other imputations including combining CFPS 2012 and 2014 follow-up data to fill in the missing information, a single imputation method, using parental educational level instead of father’s education, etc. In short, our major conclusions still hold using any of the imputation methods described.

Compared to probit and logit models, the linear probability model (LPM) produces an unbiased and consistent estimate when variables uncorrelated with the included covariates are omitted from the regression. Meanwhile, it is easier to interpret the estimated results with LPM, especially when there is an interaction term in the estimation equation (Li et al. 2014).

\(({\text{Postreform}}_{i} *\Delta {\text{supply}}_{p} )\) becomes the effect of the excluded background category (after the reform) and will not be explicitly shown. Similarly, \({\text{Postreform}}_{i}\) and \(\Delta {\text{supply}}_{p}\) become the effect of the excluded background category interacting with the Postreform dummy and supply intensity, i.e. \((B_{i} *{\text{Postreform}}_{i} )\) and \((B_{i} *\Delta {\text{supply}}_{p} )\).

For instance, when we examine the policy effects on subsamples by father’s educational level, dummies of father’s educational level will be entered into Equation (1) as B_i. Other dimensions of background variables will be entered in Xi

References

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. (2009). Most harmless econometrics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arum, R., Gamoran, A., & Shavit, Y. (2007). More inclusion than diversion: Expansion, differentiation, and market structure in higher education. In Y. Shavit, R. Arum, & A. Gamoran (Eds.), Stratification in higher education: A comparative study (pp. 1–35). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ayalon, H., & Shavit, Y. (2004). Educational reforms and inequalities in Israel: The MMI hypothesis revisited. Sociology of Education, 77(2), 103–120.

Bao, W. (2012). Mechanism and theoretical expansion of the enrollment expansion of higher education in China. Education Research Monthly, 8, 3–11.

Blanden, J., & Machin, S. (2004). Educational inequality and the expansion of UK higher education. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 51(2), 230–249.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Chan, K., & Luca, D. L. (2014). Higher education and economic growth in Africa. International Journal of African Higher Education, 1(1), 23–57.

Bratti, M., Checchi, D., & de Blasio, G. (2008). Does the expansion of higher education increase the equality of educational opportunities? Evidence from Italy. Labour, 22(S1), 53–88.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Müller, W., & Pollark, R. (2010). Long-term trends in educational inequality in Europe: Class inequalities and gender differences. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 31–48.

Callender, C., & Jackson, J. (2005). Does the fear of debt deter students from higher education? Journal of social policy, 34(4), 509–540.

Carnoy, M. (2011). As higher education expands, is it contributing to greater inequality? National Institute Economic Review, 215, R34–R47.

Carnoy, M., Loyalka, P., Androushchak, G. & Proudnikova, A. (2013). The economic returns to higher education in the BRIC countries and their implications for higher education expansion. REAP working paper No. 253., Stanford University. Retrieved from https://reap.fsi.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Economic_returns_to_higher_education_in_the_BRIC_countries2.pdf.

Carnoy, M., Loyalka, P., Dobryakova, M., Dossane, R., Froumin, I., Kuhns, K., et al. (2013b). University expansion in a changing global economy: Triumph of the BRICs?. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Chan, K. W., & Buckingham, W. (2008). Is China abolishing the Hukou system? China Quarterly, 195, 582–606.

Chan, K. W., & Zhang, L. (1999). The Hukou system and rural-urban migration in China: Process and changes. China Quarterly, 160, 818–855.

Chung, Y., Gong, F., & Lu, G. (1996). Zhongguo gaodeng jiaoyu caizheng chuyi (A discussion on higher education finance in China). Journal of Higher Education, 1996–06, 29–41.

Chung, Y., & Lu, G. (1999). Shoufei tiaojianxia xuesheng xuanze gaoxiao yingxiang yinsu fenxi. (The determinants of higher education choices under the fee-charging system). Journal of Higher Education, 1999–02, 31–41.

Davey, G., De Lian, C., & Higgins, L. (2007). The university entrance examination system in China. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31(4), 385–396.

Duflo, E. (2001). Schooling and labor market consequences of school construction in Indonesia: Evidence from an unusual policy experiment. American Economic Review, 91(4), 795–813.

Educational Statistics Yearbook of China. (2000). Beijing, China: People’s Education Press.

Educational Statistics Yearbook of China. (2008). Beijing, China: People’s Education Press.

Gallagher, M., Hasan, A., Canning, M., Newby, H., Saner-Yiu, L., & Whitman, I. (2009). OECD reviews of tertiary education: China. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/42286617.pdf.

Gou, R. (2006). Cong chengxiang gaodeng jiaoyu ruxue jihui kan gaodeng jiaoyu gongping (Examining equality in higher education from the perspective of rural-urban access to higher education). Research in Educational Development, 5, 29–31.

Gyimah-Brempong, K., Paddison, O., & Mitiku, W. (2006). Higher education and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 42(3), 509–529.

Hannum, E. (2002). Educational stratification by ethnicity in China: Enrollment and attainment in the early reform years. Demography, 39(1), 95–117.

Hanushek, E. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 37, 204–212.

Hanushek, E. (2016). Will more higher education improve economic growth? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(4), 538–552.

Hanushek, E. A., & Wöβmann, L. (2010). Education and economic growth. In D. J. Brewer & P. J. McEwan (Eds.), Economics of education (pp. 60–67). Oxford: Academic Press.

Holmes, C. (2013). Has the expansion of higher education led to greater economic growth? National Institute Economic Review, 224(1), R29–R47.

Hoxby, C. & Avery, C. (2012). The missing “one-offs”: The hidden supply of high-achieving, low income students. Brookings papers on economic activity. Retrieved from http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring%202013/2013a_hoxby.pdf.

Hoxby,C. & Turner, S. (2013). Expanding college opportunities for high-achieving, low income students. SIEPR discussion paper No. 12-014. Retrieved from http://siepr.stanford.edu/?q=/system/files/shared/pubs/papers/12-014paper.pdf.

Jensen, R. (2011). The (perceived) returns to education and the demand for schooling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 515–548.

Ju, S. (2005). Jiaoyu jihui jundengxia de woguo gaokao zhaosheng de diqu chayi (Regional disparities in university admission and equality of educational opportunities). Research of Youth, 1, 30–35.

Khor, N, Pang, L. Liu, C. Chang, F., Mo, D., Loyalka, P. & Rozelle, S. (2015). China’s looming human capital crisis: Upper secondary educational attainment rates and the middle income trap. Rural education action program working paper No. 280. Retrieved from https://reap.fsi.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/280_human_capital_paper.pdf.

Li, C. (2010). Gaodeng jiaoyu kuozhang yu jiaoyu jihui bupingdeng. (Expansion of higher education and inequality in opportunity of education: A study on effect of “Kuozhao” policy on equalization of educational attainment). Sociological Studies, 3, 83–113.

Li, S., Whalley, J., & Xing, C. (2014). China’s higher education expansion and unemployment of college graduates. China Economic Review, 30, 567–582.

Li, Y. A., Whalley, J., Zhang, S., & Zhao, X. (2011). The higher educational transformation of China and its global implications. The World Economy, 34(4), 516–545.

Liu, J. (2007). Kuozhao shiqi gaodeng jiaoyu jihui de diqu chayi yanjiu. (Examination of regional disparities of higher education opportunity during the rapid expansion period). Peking University Education Review, 5(4), 142–155.

Liu, H., & Qu, Q. (2006). Consequences of college entrance exams in China and the reform challenges. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 3(1), 7–21.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

Ma, J. (2008). Jianguo hou woguo zhongdian daxue zhaosheng difanghua wenti de yanjiu (Unpublished Master dissertation) (Research on the Enrollment Localization of Key Universities after Liberation in China). Xiamen: Xiamen University.

Machin, S., & McNally, S. (2007). Tertiary education systems and labour markets. Education and Training Policy Division, OECD.

Meng, X., Shen, K., & Xue, S. (2013). Economic reform, education expansion, and earnings inequality for urban males in China, 1988–2009. Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(1), 227–244.

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (1998). Mianxiang 21shiji jiaoyu zhenxing xingdong jihua (21st century education development action plan). Retrieved June 27, 2014, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_177/200407/2487.html.

Mok, K. H., & Wu, A. M. (2016). Higher education, changing labour market and social mobility in the era of massification in China. Journal of Education and Work, 29(1), 77–97.

Murnane, R.J. & Ganimian, A.J. (2014). Improving educational outcomes in developing countries: Lessons from rigorous evaluations. NBER working paper No. 20284. Retrieved from www.nber.org/papers/w20284.

Oppedisano, V. (2011). The (adverse) effects of expanding higher education: Evidence from Italy. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 997–1008.

Ou, D., & Kondo, A. (2013). In search of a better life: The occupational attainment of rural and urban migrants in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 46(1), 25–59.

Ou, D., & Zhao, Z. (2016). Higher education expansion and labor market outcomes for young college graduates. IZA working paper No. 9643.

Oviedo, M. J. (2009). Expansion of higher education and the equality of opportunity in Colombia (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain: Universitat Autonóma de Barcelona.

Pfeffer, F. T. (2008). Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. European Sociological Review, 24(5), 543–565.

Pissarides, C.A. (2000) Human capital and economic growth: A synthesis report, OECD Development Centre Technical papers No. 168, Paris: OECD.

Pritchett, L. (2001). Where has all the education gone? The World Bank Economic Review, 15(3), 367–391.

Qiao, J. (2007). Youzhi gaodeng jiaoyu ruxue jihui fenbu de quyu chayi (Regional differentiations of entrance opportunity for high-quality higher education). Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science), 1, 23–28.

Qiao, J., & Hong, Y. (2009). Woguo gaodeng jioayu kuozhan moshi de shizheng yanjiu (An empirical study of China’s higher education expansion mode). Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences), 2, 106–113.

Raftery, A. E., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62.

Saxenian, A. The. (2006). The new argonauts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shavit, Y., & Blossfeld, H. P. (1993). Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Shen, H. (2007). Gaodeng jiaoyu shengxue jihui diqujian bupingdeng de xianzhuang jiqi chengyin fenxi (An analysis of inequality in access to higher education among Chinese regions). Tsinghua Journal of Education, 28(3), 22–29.

Tan, M., & Xie, Z. (2009). Gaoxiao daguimo kuozhao yilai woguo shaoshu minzu gaodeng jiaoyu fazhan zhuangkuang fenxi (An analysis of higher education development for ethnic minority students after higher education expansion in China). Higher Education Exploration, 2, 26–31.

Wan, Y. (2006). Expansion of Chinese higher education since 1998: Its causes and outcomes. Asia Pacific Education Review, 7(1), 19–32.

Wang, T. Z. (2007). Preferential policies for ethnic minority students in China’s college/university admission. Asian Ethnicity, 8(2), 149–163.

Wang, W. (2013). Gaokao zhaosheng de diqu chayi yu diqu junheng: dui gaokao zhaosheng pingdengxing wenti de lingyizhong jiedu (Regional variations and equilibrium of university admission: Another look at the equity issue of university admission system). Social Scientist, 1, 53–57.

Wang, E. & Chan, K. W. (2005). Qingxie de fenshuxian—Zhongguo daxue luqu tiaojian de diqu chayi (Tilting scoreline: Geographical inequalities in admission scores to higher education in China). In C Fang & Z Zhanxin (Eds.), Labor market in China’s transition. (Chapter 3, pp. 237–266) Beijing: China Population Publishing House.

Wang, X., Fleisher, BM., Li, H., & Li, S. (2007). Access to higher education and inequality: The Chinese experiment (IZA Discussion Paper No. 2823). Retrieved from Institute for the Study of Labor website: http://ftp.iza.org/dp2823.pdf.

White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30, 377–399.

World Bank. (2006). Gender gaps in China: Facts and figures. Retrieved from World Bank website: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEAPREGTOPGENDER/Resources/Gender-Gaps-Figures&Facts.pdf.

Wu, X. & Song, X. (2013). Ethnicity, migration, and social stratification in China: Evidence from Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Population Studies Center Research Report No. 13-810. University of Michigan.

Wu, X., & Trieman, D. J. (2002). The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955–1996. Population Studies Center Research Report No. 02-499. University of Michigan.

Wu, X., & Trieman, D. J. (2004). The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955–1996. Demography, 41(2), 363–384.

Wu, X., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Changes in educational inequality in China, 1990–2005: Evidence from the population census data. Research in the Sociology of Education, 17, 123–152.

Xie, Y. (2012). China family panel studies user’s manual for the 2010 baseline survey. Retrieved from Institute of Social Science Survey website: http://www.isss.edu.cn/cfps/EN/.

Xie, Y., & Hu, J. (2014). An Introduction to the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chinese Sociological Review, 47(1), 3–29.

Xie, Y., & Lu, P. (2015). The Sampling design of the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chinese Journal of Sociology., 1(4), 471–484.

Xie Y., Qiu Z., & Lu, P. (2012). China family panel studies: Sample design for the 2010 baseline survey (Technical Report Series No. CFPS-1). Beijing, China: Institute of Social Science Survey.

Yang, G. (2014). Are all admission sub-tests created equal?—evidence from a national key university in China. China Economic Review, 30, 600–617.

Yang, D. T., & Zhou, H. (1999). Rural-urban disparity and sectoral labor allocation in China. Journal of Development Studies, 35(3), 105–133.

Yeung, N. W.-J. J. (2013). China’s higher education expansion and social stratification. Chinese Sociological Review, 45(4), 54–80.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Massimiliano Bratti, Lingxin Hao, Prashant Loyalka, Sandra McNally and audience at the 2015 AERA conference for their helpful comments. We also thank all anonymous reviewers whose comments have greatly improved this paper. Ou acknowledges funding from the CUHK Direct Grant (#4058038). The opinions expressed here represent opinions of the authors only.

Funding

Funding was provided by CUHK Direct Grant (Grant No. #4058038).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

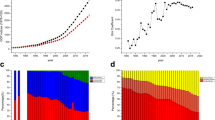

See Fig. 3 and Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, D., Hou, Y. Bigger Pie, Bigger Slice? The Impact of Higher Education Expansion on Educational Opportunity in China. Res High Educ 60, 358–391 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9514-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9514-2