Abstract

In the last three decades, the expansion of nonstandard forms of employment has involved a shift in two dimensions related to time: working time arrangements and temporary contracts, which are grouped under the umbrella term time precarity at work. Previous research has explored how atypical scheduling practices and a weak tie to the labor market affect worker’s health, well-being, family fit, and self-assessments of work-nonwork interference. However, much less is known about which specific dimensions of everyday life are affected and how these two features of time precarity interact with each other. This study analyzes how different schedule arrangements and temporary contracts associate with leisure and social time. Using data from Italy (2013–2014) and latent class analysis, four types of schedule arrangements are identified: standard, short, extended, and shift. Results from the regression analysis show that extended or shift work predicts reductions in leisure time, especially on weekends, and there is suggestive evidence that the reduction is even larger for workers with a temporary contract. Regarding social participation, extended or shift work predicts less time spent with others, and having a temporary contract or a shift schedule reduces the probability of participating in community activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data

The dataset analyzed during the current study is publicly available here: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/216733.

Notes

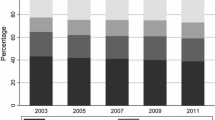

Between 2014 and 2016, in a context of increasing unemployment, an additional round of labor reforms – under the name “Jobs Act” – took place with the purpose of making the labor market even more flexible. The main innovation was the introduction of a unique labor contract for new hires with guarantees that increase over time, allowing the termination of contracts without “just cause” with a severance payment of up to 24 months, depending on tenure and size of firm. Even though these Jobs Act reforms took place after the period of analysis (2013–2014), the findings may still be relevant given that the reforms further intensify the dualism in the Italian labor market and that, as Fig. 1 shows, the use of temporary contracts gained an additional push after 2014.

The focus is on the main job. This should not introduce a significative error given that only 3% of respondents report having a secondary job.

No measure of teleworking is included given that only 1.6% of respondents report working under this modality.

Respondents were also asked if they were doing anything else at the same time, but these “secondary activities” are not used in the analyses.

The variable “involvement in social activities” shares some similarities with the previous indicator of time workers spend with their family and other nonfamily members. However, they differ in some respects. First, the dichotomous variable does not necessarily correspond to level of involvement. People who participate in several social activities do not automatically invest more time with others than someone who participates in fewer social activities. Second, the indicator of “involvement in social activities” is more specific to the workers’ abilities to maintain weaker types of social connections (Cornwell and Warburton, 2014) and, therefore, provide a better approximation at community participation.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. (2002). Work Safety in the Context of Temporary Employment: The Spanish Experience. ILR Review, 55(2), 262–285

Anttila, T., Oinas, T., Tammelin, M., Jouko, & Nätti (2015). Working-Time Regimes and Work-Life Balance in Europe. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 713–724

Barbieri, P., Bozzon, R., Scherer, S., Grotti, R., & Lugo, M. (2015). The Rise of a Latin Model? Family and Fertility Consequences of Employment Instability in Italy and Spain. European Societies, 17(4), 423–446

Barbieri, P., and Stefani Scherer (2009). Labour Market Flexibilization and Its Consequences in Italy. European Sociological Review, 25(6), 677–692

Berg, P., Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2004). Contesting Time: International Comparisons of Employee Control of Working Time. ILR Review, 57(3), 331–349

Berg, P., Bosch, G., & Charest, J. (2014). Working-Time Configurations: A Framework for Analyzing Diversity across Countries. ILR Review, 67(3), 805–837

Bittman, M., and Judy Wajcman (2000). The Rush Hour: The Character of Leisure Time and Gender Equity. Social Forces, 79(1), 165–189

Blair-Loy, M., & Cech, E. A. (2017). Demands and Devotion: Cultural Meanings of Work and Overload Among Women Researchers and Professionals in Science and Technology Industries. Sociological Forum, 32(1), 5–27

Blanchard, O., & Landier, A. (2002). The Perverse Effects of Partial Labour Market Reform: Fixed-Term Contracts in France. The Economic Journal, 112(480), F214–F244

Blyton, P., & Jenkins, J. (2012). Life after Burberry: Shifting Experiences of Work and Non-Work Life Following Redundancy. Work Employment and Society, 26(1), 26–41

Boeri, T. (2011). “Institutional Reforms and Dualism in European Labor Markets.” In Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol 4B, edited by O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, 1173–1236. Elsevier

Booth, A. L., Francesconi, M., & Jeff Frank. (2002). Temporary Jobs: Stepping Stones or Dead Ends? The Economic Journal, 112(480), F189–213

Boulin, J. Y., Lallement, M., Messenger, J. C., François, & Michon (Eds.). (2006). Decent Working Time: New Trends, New Issues. Geneva: International Labour Office

Brand, J. E. (2015). The Far-Reaching Impact of Job Loss and Unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 359–375

Brand, Jennie E., & Sarah A. Burgard (2008). Job Displacement and Social Participation over the Lifecourse: Findings for a Cohort of Joiners. Social Forces, 87(1), 211–242

Breen, R., Karlson, B., Kristian, & Holm, A. (2021). A Note on a Reformulation of the KHB Method. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(2), 901–912

Cahuc, P., Charlot, O., & Malherbet, F. (2016). Explaining the Spread of Temporary Jobs and Its Impact on Labor Turnover. International Economic Review, 57(2), 533–572

Collins, Linda M. & Stephanie T. Lanza (2010). Latent Class Analysis and Latent Transition Analysis. With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. New Jersey: Willy

Cornwell, B., and Elizabeth Warburton (2014). Work Schedules and Community Ties. Work and Occupations, 41(2), 139–174

Cornwell, B., Gershuny, J., & Sullivan, O. (2019). The Social Structure of Time: Emerging Trends and New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 301–320

Craig, L., and Killian Mullan (2010). Parenthood, Gender and Work-Family Time in the United States, Australia, Italy, France, and Denmark. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1344–1361

Craig, L., & Powell, A. (2011). Non-Standard Work Schedules, Work-Family Balance and the Gendered Division of Childcare. Work Employment and Society, 25(2), 274–291

Cutuli, G., & Guetto, R. (2013). Fixed-Term Contracts, Economic Conjuncture, and Training Opportunities: A Comparative Analysis Across European Labour Markets. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 616–629

Engellandt, Axel, & Regina T. Riphahn (2005). Temporary Contracts and Employee Effort. Labour Economics, 12(3), 281–299

Faccini, R. (2014). Reassessing Labour Market Reforms: Temporary Contracts as a Screening Device. The Economic Journal, 124(575), 167–200

Fagan, C., Lyonette, C., Smith, M., & Abril Saldaña-Tejeda. (2012). The Influence of Working-Time Arrangements on Work-Life Integration or ‘Balance’: A Review of the International Evidence. ” Geneva: International Labor Organization

Fiori, F., Rinesi, F., Spizzichino, D., & Ginevra Di Giorgio. (2016). Employment Insecurity and Mental Health during the Economic Recession: An Analysis of the Young Adult Labour Force in Italy. Social Science & Medicine, 153, 90–98

Flood, S. M., Hill, R., & Katie, R. G. (2018). Daily Temporal Pathways: A Latent Class Approach to Time Diary Data. Social Indicators Research, 135(1), 117–142

Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). Temporary Employment and Employability: Training Opportunities and Efforts of Temporary and Permanent Employees in Belgium. Work Employment and Society, 17(4), 641–666

Gagliarducci, S. (2005). The Dynamics of Repeated Temporary Jobs. Labour Economics, 12(4), 429–448

Garibaldi, P., & Taddei, F. (2013). “Italy: A Dual Labour Market in Transition: Country Case Study on Labour Market Segmentation. ” Geneva: International Labor Organization

Gash, V., & McGinnity, F. (2007). Fixed-Term Contracts—the New European Inequality? Comparing Men and Women in West Germany and France. Socio-Economic Review, 5(3), 467–496

Gebel, M. (2010). Early Career Consequences of Temporary Employment in Germany and the UK. Work Employment and Society, 24(4), 641–660

Gershuny, J. (2000). Work and Leisure in Postindustrial Society. New York: Oxford University Press

Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2018). Control over Time: Employers, Workers, and Families Shaping Work Schedules. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 77–97

Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class Advantage and the Gender Divide: Flexibility on the Job and at Home. American Journal of Sociology, 120(2), 395–431

Giaccone, M. (2009). “Working Time in the European Union: Italy.” Eurofound. 2009. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2009/working-time-in-the-european-union-italy

Giesecke, J. (2009). Socio-Economic Risks of Atypical Employment Relationships: Evidence from the German Labour Market. European Sociological Review, 25(6), 629–646

Gundert, S., & Hohendanner, C. (2014). Do fixed-term and temporary agency workers feel socially excluded? Labour market integration and social well-being in Germany. Acta Sociologica, 57(2), 135–152

International Labour Organization. (2008). “Measurement of Working Time. ” Geneva: International Labor Organization.

International Labour Organization. (2016). Non-Standard Employment around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects. Geneva: International Labor Organization

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). (2019). I Tempi della Vita Quotidiana. Lavoro, Conciliazione, Parità di Genere e Benessere Soggettivo. Rome: ISTAT

Jacobs, J. A., and Kathleen Gerson (2001). Overworked Individuals or Overworked Families? Explaining Trends in Work, Leisure, and Family Time. Work and Occupations, 28(1), 40–63

Jaramillo, M., & Campos, D. “Revisiting the Steppingstone Hypothesis: Transitions from Temporary to Permanent Contracts in Peru.” International Labour Review, Forthcoming

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22

Kalleberg, A. L., & Steven P. Vallas (2017). “Probing Precarious Work: Theory, Research, and Politics.” In Precarious Work (Research in the Sociology of Work, Vol 31), edited by Arne L. Kalleberg and Steven P. Vallas, 1–30. Emerald Publishing Limited

Karlson, Kristian Bernt, Holm, Anders, & Richard, Breen (2012). Holm, Anders, and Richard, Breen. “Comparing Regression Coefficients Between Same-sample Nested Models Using Logit and Probit: A New Method.” Sociological Methodology 42 (1): 286–313

Kauhanen, M., & Jouko, Nätti (2015). Involuntary Temporary and Part-Time Work, Job Quality and Well-Being at Work. Social Indicators Research, 120(3), 783–799

Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., & Tranby, E. (2011). Changing Workplaces to Reduce Work-Family Conflict: Schedule Control in a White-Collar Organization. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 265–290

László, K. D., Pikhart, H., Kopp, M. S., Bobak, M., Pajak, A., Malyutina, S., Gyöngyvér … Marmot, M. (2010). “Job Insecurity and Health: A Study of 16 European Countries.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (6): 867–74

Luckmann, T. (1991). “The Constitution of Human Life in Time.” In Chronotypes: The Construction of Time, edited by John Bender and David Wellbery, 151–66. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Messenger, J. (2018). “Working Time and the Future of Work.”. Geneva: International Labour Office

Moscone, F., Tosetti, E., & Vittadini, G. (2016). The Impact of Precarious Employment on Mental Health: The Case of Italy. Social Science & Medicine, 158, 86–95

OECD (1998). “Working Hours: Latest Trends and Policy Initiatives.” In OECD Employment Outlook:June, 153–88. Paris: OECD Publishing

OECD. “Italy: The Treu (1997) and Biagi (2002) Reforms.” In The Political Economy of Reform: Lessons from Pensions, Product Markets and Labour Markets in Ten OECD Countries, 247–68. Paris: OECD Publishing

OECD (2020). Hours worked (indicator). doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/47be1c78-en (Accessed on 20 December 2021).

OECD (2020). Temporary employment (indicator). doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/75589b8a-en (Accessed on 20 December 2021)

OECD (2020). Part-time employment rate (indicator). doi: https://doi.org/10.1787/f2ad596c-en (Accessed on 20 December 2021).

Pirani, E., & Salvini, S. (2015). Is Temporary Employment Damaging to Health? A Longitudinal Study on Italian Workers. Social Science & Medicine, 124, 121–131

Quesnel-Vallée, A., DeHaney, S., & Antonio Ciampi. (2010). Temporary Work and Depressive Symptoms: A Propensity Score Analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 70(12), 1982–1987

Rotolo, T., and John Wilson (2003). Work Histories and Voluntary Association Memberships. Sociological Forum, 18(4), 603–619

Scherer, S. (2009). The Social Consequences of Insecure Jobs. Social Indicators Research, 93(3), 527–547

Schieman, S., & Milkie, M. A., and Paul Glavin (2009). When Work Interferes with Life: Work-Nonwork Interference and the Influence of Work-Related Demands and Resources. American Sociological Review, 74(6), 966–988

Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2019). Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for Worker Health and Well-Being. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 82–114

Sennett, R. (1998). The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism. New York: Norton

Standing, G. (2011). “Labour, Work and the Time Squeeze.” In The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, by Guy Standing, 115–131. London: Bloomsbury Academic

Steiber, N. (2009). Reported Levels of Time-Based and Strain-Based Conflict between Work and Family Roles in Europe: A Multilevel Approach. Social Indicators Research, 93(3), 469–488

Su, J., Houston, & Dunifon, R. (2017). Nonstandard Work Schedules and Private Safety Nets Among Working Mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(3), 597–613

Thompson, E. P. (1967). Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism. Past and Present, 38(1), 56–97

Vagni, G. (2020). The Social Stratification of Time Use Patterns. The British Journal of Sociology, 71, 658–679

Van Aerden, K., Puig-Barrachina, V., Bosmans, K., & Vanroelen, C. (2016). How Does Employment Quality Relate to Health and Job Satisfaction in Europe? A Typological Approach. Social Science and Medicine, 158, 132–140

Veblen, Thorstein ([1899] 2004). Teoría de La Clase Ociosa. Madrid: Alianza Editorial

Vignoli, D., Drefahl, S., & Gustavo De Santis. (2012). Whose Job Instability Affects the Likelihood of Becoming a Parent in Italy? A Tale of Two Partners. Demographic Research, 26, 41–62

Virtanen, P., Vahtera, J., Kivimäki, M., Liukkonen, V., Virtanen, M., & Ferrie, J. (2005). Labor Market Trajectories and Health: A Four-Year Follow-up Study of Initially Fixed-Term Employees. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(9), 840–846

Wang, M. C., Deng, Qiaowen, Bi, Xiangyang, Ye, Haosheng, and, & Yang, W. (2017). “Performance of the entropy as an index of classification accuracy in latent profile analysis: A Monte Carlo simulation study.” Acta Psychologica Sinica 49 (11): 1473–1482

Wiens-Tuers, B. A. (2004). There’s No Place Like Home. The Relationship of Nonstandard Employment and Home Ownership Over the 1990s. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 63(4), 881–896

Winship, C. (2011). “Time and Scheduling.” In The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology, edited by Peter Hedstrom and Peter Bearman, 498–520. New York: Oxford University Press

Wynn, A. T. (2018). Misery Has Company: The Shared Emotional Consequences of Everwork Among Women and Men. Sociological Forum, 33(3), 712–734

Zerubavel, E. (1981). Hidden Rhythms. Schedules and Calendars in Social Life. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press

Funding

The initial research on this project was supported by the Graduate School, part of the Office of Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and the UW-Madison.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campos Ugaz, D. Time precarity at work: nonstandard forms of employment and everyday life. Soc Indic Res 164, 969–991 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02954-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02954-1