Abstract

Quantitative research methods are used to examine the interaction among public disability benefit receipt, substance abuse, participation in substance abuse treatment, and employment among US adults. Using cross-sectional data from the 2002 and 2003 Survey on Drug Abuse and Health, the results demonstrate that disability beneficiaries who have substance use disorders are more likely to access treatment than persons with substance use disorders who are not beneficiaries. Results could not confirm, however, that those beneficiaries who access treatment are more likely to return to employment than those who do not access treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Positive constructions include images such as ‘deserving,’ ‘intelligent,’ ‘honest,’ ‘public spirited,’ and so forth. Negative constructions include images such as ‘undeserving’, ‘stupid’, ‘dishonest’, and ‘selfish’” (Schneider and Ingram,1 p. 335).

In keeping with the focus on personal responsibility and employment, for example, SSA implemented the Ticket to Work program in 1999, providing every disability beneficiary with an opportunity to select an employment service provider of their choice to pursue employment. While there is no specific requirement that beneficiaries must participate in this program, the program is designed to provide monetary incentives to both beneficiaries and employment service providers in an attempt to encourage participation. The program is currently being evaluated. As with other SSA employment demonstrations, participation from beneficiaries has thus far been low.9

Treatment receipt was significant in all five models for non-beneficiaries, although in a negative direction, suggesting that those who participated in treatment during the past year were less likely to be employed during the past week. The odds ratio for treatment in the final model was 0.627, indicating that the odds of working for persons who participated in treatment were 37% lower than the odds of substance abusing persons who did not participate in treatment, holding all other variables equal. Type of abuse or dependence was significant for non-beneficiaries, with persons with illicit drug abuse or dependence less likely to be employed than persons who did not have illicit drug abuse or dependence. Age, gender, race, education, and marital status were significant for the non-beneficiary models, with older, white, educated, married males more likely to be employed. Survey year was significant at the 0.05 level, with persons completing the 2002 survey more likely to be employed than those that completed the 2003 survey.

Results available from author.

Brucker, D. Comparative analysis: Substance abuse, disability and public disability programs. Working paper, 2007.

References

Schneider A, Ingram H. Social construction of target populations: implications for politics and policy. American Political Science Review. 1993;87(2):334–347.

Stone D. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, revised edition. New York: WW Norton; 2002.

Stone D. Introduction: public policy and social construction of deservedness. In: Schneider A, Ingram H, eds. Deserving and Entitled: Social Constructions and Public Policy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2005.

Schneider A, Ingram H. Constructing and entitling America’s original veterans. In: Schneider A, Ingram H, eds. Deserving and Entitled: Social Constructions and Public Policy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2005.

Liberman RC. Social construction. American Political Science Review. 1995;89(2):437–441.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Transforming Disability Into Ability: Policies to Promote Work and Income Security for Disabled People. Paris, France: OECD; 2003.

Esping-Anderson G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1990.

Gilbert N. Transformation of the Welfare State: The Silent Surrender of Public Responsibility. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004:78.

Mathematica Policy Research. Ticket to Work: Helping the Disabled Find and Keep Jobs. http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/disability/tickettowork.asp. Cited January 27, 2007.

General Accounting Office (GAO). Social Security: Disability Programs Lag in Promoting Return to Work, Letter Report to Congressional Committee. Washington, DC: GAO; 1997.

Watkins KE, Podus D. The impact of terminating disability benefits for substance abusers on substance use and treatment participation. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(11):1371–1381.

Stapleton DC. The eligibility definition used in the Social Security Administration’s disability programs needs to be changed. Prepared for presentation at the Social Security Advisory Board’s April 14, 2004 Discussion Forum on the Definition of Disability. http://www.ssab.gov/DisabilityForum/SSAB%20forum%20Stapleton%20presentation.pdf. Cited August 4, 2005.

Rangarajan A, Sarin A, Brucker D. Programmes to Promote Employment for the Disabled: Lessons from the United States. Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research; 2005.

Fraker T, Moffitt R. The effects of food stamps on labor supply: a bivariate selection model. Journal of Public Economics. 1988;35(1):25–56.

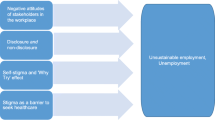

Gerry M. Comprehensive Work Opportunity Initiative: Overcoming Multiple Barriers to Employment (Figure 1). DRI News, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois; 2005:5(2).

Knox V, Miller C, Gennetian LA. Reforming Welfare and Rewarding Work: A Summary of the Final Report on the Minnesota Family Investment Program. New York: MDRC; 2000.

Ireys H, White JS, Thornton C. The Medicaid Buy-In Program: Quantitative Measures of Enrollment Trends and Participant Characteristics in 2002. Preliminary Report. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; 2003.

Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al. Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: Critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management & Health Outcomes. 2001;9:141–159.

Decker P, Thornton C. The long-term effects of transitional employment services. Social Security Bulletin. 1995;58:71–81.

Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al. Implementing evidence based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification. 2003;27(3):387–411.

Rupp K, Bell S. Paying for Results in Vocational Rehabilitation: Will Provider Incentives Work for Ticket to Work? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2003.

General Accounting Office. Social Security: Major Changes Needed for Disability Benefits for Addicts. GAO/HEHS-94-128. Washington, DC: GAO; 1994.

Nibali K. Testimony given as Associate Commissioner for Disability, from the 9/12/00 hearing on the “Inspector General Report on the Implementation of the Drug Addiction and Alcoholism Provisions of the PL 104-121”. http://www.ssa.gov/legislation/testimony_091200.html.

Watkins KE, Podus D. The impact of terminating disability benefits for substance abusers on substance use and treatment participation. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(11):1371–1381.

Kulka RA, Eyerman J, McNeeley ME. The use of monetary incentives in federal surveys on substance use and abuse. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement. 2005;30:233–249.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition. Washington, DC: APA; 1994.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Appendix C. Measurement of dependence, abuse, treatment and treatment need. http://oas.samhsa.gov/Dependence/appendixc.htm.

Brucker, D. Estimating the prevalence of substance use, abuse and dependence among social security diability benefit recipients. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2007;18(3) (in press).

National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main findings 1990. Rockville, MD: NIDA; 1990.

Long JS. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997.

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The NBER’s Recession Dating Procedure, 2003. http://www.nber.org/cycles/recessions.html. Cited July 30, 2006.

Pearson G. The willingness for substance abuse treatment services among adults in a rural setting. Brandeis Graduate Journal. 2004;2:1–9.

Acemoglu D, Angrist J. Consequences of employment protection? The case of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Journal of Political Economy. 2001;109:915–957.

DeLeire T. The Americans with Disabilities Act and the employment of people with disabilities. In: Stapleton D, Burkhauser R, eds. The Decline in Employment of People with Disabilities: A Policy Puzzle. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research; 2003.

Speiglman R. Effects of the elimination of SSI drug addition and alcoholism eligibility; 1997. http://www.saprp.org/FundedGrants/FindingsSummaries/Speiglman.html. Cited December 11, 2003.

Zedlewski S, Nelson S, Edin K, et al. Families coping without earnings or government cash assistance. Occasional Paper No. 64, Assessing the New Federalism. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Radha Jagannathan, Joel Cantor, Joceyln Crowley, Carol Harvey, and two anonymous reviewers for their recommendations, challenges, insight, and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brucker, D.L. Substance Abuse Treatment Participation and Employment Outcomes for Public Disability Beneficiaries with Substance Use Disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res 34, 290–308 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-007-9073-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-007-9073-3