Abstract

Freedom is highly valued, but there are limits to the amount of freedom a society can allow its members. This begs the question of how much freedom is too much. The answers to that question differ across political cultures and are typically based on ideological argumentation. In this paper, we consider the compatibility of freedom and happiness in nations by taking stock of the research findings on that matter, gathered in the World Database of Happiness. We find that freedom and happiness are positively correlated in contemporary nations. The pattern of correlation differs somewhat across cultures and aspects of freedom. We found no pattern of declining happiness returns, which suggests that freedom has not passed its maximum in the freest countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

29 August 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

Notes

The six determinants are GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, generosity, freedom from corruption, and freedom to make life choices. Together, these six variables explain 74% of the variation (adjusted R-squared) in the national annual average ladder scores of countries (Helliwell et al. 2017).

A full description of the construction of the index is available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2016/methodology

This proposition, as well as the one in the previous paragraph are not new, and are built on past theories and literature that are not within the scope of our study. The publications by Inglehart, Welzel, and Klingemann are the most relevant to our study as they also provide empirical evidence of the human development syndrome. A detailed theoretical background is available in Welzel et al. (2003) and Welzel (2013).

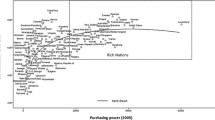

The happiness measure used is the average response to the Cantril ladder question, which asks respondents to rate their quality of life on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of happiness. It is the average response for the years 2013–2015, obtained from the World Happiness Report 2016 (Helliwell et al. 2016). The measure of economic freedom is on a scale from 1 to 10, where higher values indicate higher levels of economic freedom, obtained from the Economic Freedom of the World Report 2015 (Gwartney et al. 2015). The measure of perceived freedom is on a scale of 1 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of perceived freedom. It is obtained from the sixth wave of the World Values Survey, conducted in the years 2012–2014, and is described in detail in Section 2.3 above.

The link to the WDH finding page for the relationship between economic freedom and happiness in Gehring (2013) is: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

This distinction is stated in the page that lists the research findings on the World Database of Happiness, accessible from the table by Control + Click on the symbols representing each association.

Findings in the World Database of Happiness: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

References

Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Do economic reforms alleviate subjective well-being losses of economic crises? Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 163–182. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9442-y.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2007). The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world. Public Choice, 130(3–4), 267–292. doi:10.1007/s11127-006-9081-5.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 419–430. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.001.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101. doi:10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation 1990 (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Elliott, M., & Hayward, R. D. (2009). Religion and life satisfaction worldwide: the role of government regulation*. Sociology of Religion, 70(3), 285–310. doi:10.1093/socrel/srp028.

Freedom House (2016). Freedom in the World 2016. Retrieved from www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2016.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. The Journal of Human Resources, 39(3), 649–674. doi:10.2307/3558991.

Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from Freedom (Reprint). New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Gehring, K. (2013). Who benefits from economic freedom? Unraveling the effect of economic freedom on subjective well-being. World Development, 50, 74–90. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.003.

Gerring, J., Bond, P., Barndt, W. T., & Moreno, C. (2005). Democracy and economic growth: a historical perspective. World Politics, 57(3), 323–364.

Gwartney, J. D., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2015). Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report. Fraser Institute. Retrieved from www.fraserinstitute.org.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2016). World Happiness Report 2016, Update (Vol. I). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2017). World Happiness Report 2017. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics and Politics, 12(1), 1–31. doi:10.1111/1468-0343.00066.

Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(2), 355–389. doi:10.1093/icc/11.2.355.

Heston, A., Summers, R., & Aten, B. (2002). Penn World Table Version 6.1. Center for International Comparisons at the University of Pennsylvania (CICUP).

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: SAGE.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Humana, C. (1992). World human rights guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: the human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackman, R. W., & Miller, R. A. (1998). Social capital and Politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 47–73. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.47.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1682130). Rochester: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1682130.

Miller, T., & Kim, A. (2016). 2016 Index of Economic Freedom. The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Muller, E. N., & Seligson, M. A. (1994). Civic culture and democracy: the question of causal relationships. The American Political Science Review, 88(3), 635–652. doi:10.2307/2944800.

Rode, M. (2012). Do good institutions make citizens happy, or do happy citizens build better institutions? Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(5), 1479–1505. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9391-x.

Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: a case history of a variable. American Psychologist, 45(4), 489–493. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.489.

Rustow, D. A. (1970). Transitions to democracy: toward a dynamic model. Comparative Politics, 2(3), 337–363. doi:10.2307/421307.

Schwartz, B. (2009). The paradox of choice. New York: Harper Collins.

Smart, J. J. C., & Williams, B. (1973). Utilitarianism: for and against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsai, M.-C. (2009). Market openness, transition economies and subjective Wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 523–539. doi:10.1007/s10902-008-9107-4.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34. doi:10.1007/BF00292648.

Veenhoven, R. (1999). Quality-of-life in individualistic society. Social Indicators Research, 48(2), 159–188. doi:10.1023/A:1006923418502.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Freedom and happiness: a comparative study in forty-four nations in the early 1990s. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 257–288). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess how happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. In A. K. Dutt & B. Radcliff (Eds.), Happiness, Economics and Politics: towards a multi-disciplinary approach (pp. 45–69). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Veenhoven, R. (2010). How universal is happiness? In E. Diener, D. Kahneman, & J. Helliwell (Eds.), International differences in well-being (pp. 328–350). New York: Oxford University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2012). Cross-national differences in happiness: cultural measurement bias or effect of culture? International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(4). doi:10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.4.

Veenhoven, R. (2015). Informed pursuit of happiness: what we should know, do know and can get to know. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 1035–1071. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9560-1.

Veenhoven, R. (2017). World database of happiness: archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life. Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl.

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2014). The Easterlin illusion: economic growth does go with greater happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1(4), 311–343. doi:10.1504/IJHD.2014.066115.

Wacziarg, R., & Welch, K. H. (2008). Trade liberalization and growth: new evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 22(2), 187–231. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn007.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, C., & Inglehart, R. (2010). Agency, values, and well-being: a human development model. Social Indicators Research, 97(1), 43–63. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9557-z.

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2003). The theory of human development: a cross-cultural analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 42(3), 341–379. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00086.

World Bank. (2016). World development indicators 2016. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/datacatalog/world-development-indicators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: modifications have been made to Tables 2, 3, and 4, captions to Figs. 2 and 3, and hyperlinks to the findings pages on the World Database of Happiness in page 11. Full information regarding corrections made can be found in the erratum for this article.

Ruut Veenhoven is on the Editorial Policy Board of the Applied Research in Quality-of-Life journal, and one of the Board of Directors of the International Society of Quality-of-Life Studies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abdur Rahman, A., Veenhoven, R. Freedom and Happiness in Nations: A Research Synthesis. Applied Research Quality Life 13, 435–456 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6