ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Professional organizations have issued guidelines recommending breast cancer screening for women 50 years of age.

OBJECTIVE

This study examines the percent of U.S. primary care physicians who report breast cancer screening practices that are not consistent with guidelines, and the characteristics of physicians who reported offering extra test modalities.

DESIGN

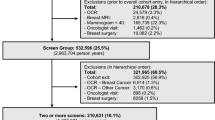

We analyzed a subset of a 2008 cross-sectional Women’s Health Care survey sent to primary care physicians randomly selected from the national American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile. A subset of physicians received a survey that presented a vignette of a health maintenance visit for an asymptomatic 51-year-old woman who was not at high risk for breast cancer. Responses were weighted to represent physicians nationally.

PARTICIPANTS

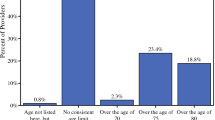

1,654 U.S. family physicians, general internists, and obstetrician-gynecologists under age 65, who practiced in office or hospital based settings (62.8 % response rate). After exclusions, 553 study physicians remained for analysis.

MAIN MEASURE

Physician self-report of breast cancer screening practices that are not consistent with the recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), and the American Cancer Society (ACS), defined as almost always offering mammography.

KEY RESULTS

36.0 % (95 % CI: 31.8 %–40.5 %) of physicians reported offering breast cancer screening tests inconsistent with national guidelines, with most offering extra tests (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] and/or ultrasound) (33.2 %, 95 % CI 29.1 %–37.6 %). In adjusted analysis, risk-averse physicians and those who believed in the clinical effectiveness of MRI were more likely to offer extra breast cancer screening tests.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians often report offering breast cancer screening test modalities beyond those recommended for a 51-year-old woman. Strategies, such as academic detailing regarding appropriate use of technology and provision of clinical decision support for breast cancer screening, could decrease overuse of resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013.

Andersson I, Aspegren K, Janzon L, et al. Mammographic screening and mortality from breast cancer: the malmo mammographic screening trial. BMJ. 1988;297(6654):943–8.

Tabar L, Fagerberg G, Duffy SW, Day NE, Gad A, Grontoft O. Update of the swedish two-county program of mammographic screening for breast cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30(1):187–210.

Roberts MM, Alexander FE, Anderson TJ, et al. Edinburgh trial of screening for breast cancer: mortality at seven years. Lancet. 1990;335(8684):241–6.

Frisell J, Eklund G, Hellstrom L, Lidbrink E, Rutqvist LE, Somell A. Randomized study of mammography screening–preliminary report on mortality in the stockholm trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1991;18(1):49–56.

Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1541–9.

Clasen CM, Vernon SW, Mullen PD, Jackson GL. A survey of physician beliefs and self-reported practices concerning screening for early detection of cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(6):841–9.

Richards C, Klabunde C, O'Malley M. Physicians’ recommendations for colon cancer screening in women. too much of a good thing? Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(3):246–9.

Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(4):339–59.

Coughlin SS, Breslau ES, Thompson T, Benard VB. Physician recommendation for papanicolaou testing among U.S. women, 2000. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(5):1143–8.

Roetzheim RG, Fox SA, Leake B. Physician-reported determinants of screening mammography in older women: the impact of physician and practice characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(12):1398–402.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. number 42, april 2003. breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(4):821–31.

American College of Radiology. ACR practice guideline for the performance of screening and diagnostic mammography. Available at: http://www.acr.org/∼/media/3484CA30845348359BAD4684779D492D.pdf. Accessed July 10th, 2013.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American cancer society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(1):11–25. quiz 49–50.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;15(10):716–26. W-236.

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American cancer society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75–89.

American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):372–82.

DuBard CA, Schmid D, Yow A, Rogers AB, Lawrence WW. Recommendation for and receipt of cancer screenings among medicaid recipients 50 years and older. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):2014–21.

Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):260–75.

Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 national health interview survey. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1528–40.

Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Han PK, Benard VB, Breen N. Breast cancer screening beliefs, recommendations and practices: primary care physicians in the United States. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3101–11.

Goff BA, Matthews B, Andrilla CH, et al. How are symptoms of ovarian cancer managed?: A study of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2011;117(19):4414–23.

Trivers KF, Baldwin LM, Miller JW, et al. Reported referral for genetic counseling or BRCA 1/2 testing among United States physicians: A vignette-based study. Cancer. 2011;117(23):5334–43.

Goff BA, Miller JW, Matthews B, et al. Involvement of gynecologic oncologists in the treatment of patients with a suspicious ovarian mass. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):854–62.

Kadivar H, Goff BA, Phillips WR, Andrilla CH, Berg AO, Baldwin LM. Nonrecommended breast and colorectal cancer screening for young women: A vignette-based survey. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):231–9.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–22.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al. Measuring the quality of physician practice by using clinical vignettes: a prospective validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):771–80.

Dresselhaus TR, Peabody JW, Luck J, Bertenthal D. An evaluation of vignettes for predicting variation in the quality of preventive care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(10):1013–8.

Henderson JT, Weisman CS, Grason H. Are two doctors better than one? Women’s physician use and appropriate care. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12(3):138–49.

Stovall DW, Loveless MB, Walden NA, Karjane N, Cohen SA. Primary and preventive healthcare in obstetrics and gynecology: a study of practice patterns in the mid-atlantic region. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(1):134–8.

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar D, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast-cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–86. doi:10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879.

Benichou J, Gail M, Mulvihill J. Graphs to estimate an individualized risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):103–10.

National Cancer Institute. Breast cancer risk assessment tool. Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool Web site. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/. Accessed July 10th, 2013.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1975.

Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(4):665–83.

Millstein S. Utility of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior for predicting physician behavior: a prospective analysis. Heal Psychol. 1996;15(5):398–402.

Molenaar S, Sprangers M, Postma-Schuit F, et al. Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Medical Decision Making. 2000;20(1):112–27.

Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):557–64.

Katz DA, Williams GC, Brown RL, et al. Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(6):525–33.

Franks P, Williams GC, Zwanziger J, Mooney C, Sorbero M. Why do physicians vary so widely in their referral rates? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(3):163–8.

Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart LG. Metropolitan, urban, and rural commuting areas: toward a better depiction of the US settlement system. Urban Geography. 1999;20(8):727–48.

Economic Research Service. Measuring rurality: Rural–urban commuting area codes. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/Rurality/RuralUrbanCommutingAreas/. Accessed July 10th, 2013.

Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):618–23.

Miller JW, King JB, Joseph DA, Richardson LC. Breast cancer screening among adult women--behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;15(61):46–50.

Hillman BJ. Government health policy and the diffusion of new medical devices. Health Serv Res. 1986;21(5):681–711.

Geigle R. Federal efforts at reducing health care costs: the effect on technology, part 2. Biomed Instrum Technol. 1990;24(4):249–53.

Pines JM, Isserman JA, Szyld D, Dean AJ, McCusker CM, Hollander JE. The effect of physician risk tolerance and the presence of an observation unit on decision making for ED patients with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(7):771–9.

Pines JM, Hollander JE, Isserman JA, et al. The association between physician risk tolerance and imaging use in abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(5):552–7.

Klingman D, Localio AR, Sugarman J, et al. Measuring defensive medicine using clinical scenario surveys. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1996;21(2):185–217.

Wertman BG, Sostrin SV, Pavlova Z, Lundberg GD. Why do physicians order laboratory tests? A study of laboratory test request and use patterns. JAMA. 1980;243(20):2080–2.

Williams SV, Eisenberg JM, Pascale LA, Kitz DS. Physicians’ perceptions about unnecessary diagnostic testing. Inquiry. 1982;19(4):363–70.

Hermer LD, Brody H. Defensive medicine, cost containment, and reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):470–3.

Baldor RA, Quirk ME, Dohan D. Magnetic resonance imaging use by primary care physicians. J Fam Pract. 1993;36(3):281–5.

Boetes C. Update on screening breast MRI in high-risk women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38(1):149–58.

Yau EJ, Gutierrez RL, DeMartini WB, Eby PR, Peacock S, Lehman CD. The utility of breast MRI as a problem-solving tool. Breast J. 2011;17(3):273–80.

DeMartini WB, Ichikawa L, Yankaskas BC, et al. Breast MRI in community practice: equipment and imaging techniques at facilities in the breast cancer surveillance consortium. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7(11):878–84.

Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Larson EB. Rising use of diagnostic medical imaging in a large integrated health system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1491–502.

Lehnert BE, Bree RL. Analysis of appropriateness of outpatient CT and MRI referred from primary care clinics at an academic medical center: how critical is the need for improved decision support? J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7(3):192–7.

Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: A systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153(10):1423–31.

Roshanov PS, You JJ, Dhaliwal J, et al. Can computerized clinical decision support systems improve practitioners’ diagnostic test ordering behavior? A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:88.

Souza NM, Sebaldt RJ, Mackay JA, et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for primary preventive care: a decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011;6:87.

Garg AX, Adhikari NKJ, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes - A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–38.

Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3(6):399–409.

Flottorp S, Oxman A, Havelsrud K, Treweek S, Herrin J. Cluster randomised controlled trial of tailored interventions to improve the management of urinary tract infections in women and sore throat. Br Med J. 2002;325(7360):367–70.

Roshanov PS, Fernandes N, Wilczynski JM, et al. Features of effective computerised clinical decision support systems: Meta-regression of 162 randomised trials. Br Med J. 2013;346:f657.

Tierney W, Miller M, McDonald C. The effect on test ordering of informing physicians of the charges for outpatient diagnostic-tests. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1499–504.

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We thank Barbara Matthews, MBA (University of Washington [UW]) and Denise Lishner, MSW (UW) for their administrative help; Barbara Mathews, MBA (UW) for providing the database; Blythe Ryerson, MPH (CDC) for her early contributions to the development of the Women’s Health Survey study’s methods; and Donna Berry, RN PhD (Dana Farber Cancer Institute), Barbara Matthews, MBA (UW), Denise Lishner, MSW (UW), Katrina F. Trivers, PhD (CDC), and Jacqueline W. Miller, MD (CDC) for their contributions to the development of the Women’s Health Survey. Gilmore Research Group in Seattle, Washington conducted the survey.

Funders: This project was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the University of Washington Health Promotion Research Centers Cooperative Agreement U48DP001911, and through the Alliance for Reducing Cancer, Northwest (ARC NW), funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Grant U48DP001911, V. Taylor, PI), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the University of Washington Primary Care Research (NRSA) Fellowship, funded by HRSA. The findings and conclusions of this journal article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, or the University of Washington.

Prior presentations: Kadivar H, Goff B, Phillips W, Berg A, Andrilla H, Baldwin LM. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force-Inconsistent Screening for Breast and Colorectal Cancer. Poster presentation, Academy Health Annual Research, Seattle, Washington. June 13, 2011.

Conflict of Interest

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts related to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kadivar, H., Goff, B.A., Phillips, W.R. et al. Guideline-Inconsistent Breast Cancer Screening for Women over 50: A Vignette-Based Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 82–89 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2567-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2567-1