Abstract

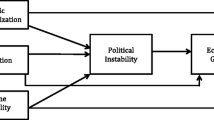

The influence of “ethnic politics” has been demonstrated in a range of empirical studies of economic growth, violence, and public goods provision. While others have raised concerns about the measurement of ethnic variables in these works, we seek to situate such discussions within a more thoroughgoing conceptual analysis. Specifically, we argue that four conceptual approaches—demographic, cognitive, behavioral, and institutional—have been used to develop theories in which the mechanism that relates causes to outcomes is ethnic political competition. Within this literature, we believe that institutional approaches have been relatively under-appreciated, and we attempt to address that imbalance. We begin by critically reviewing the three main ways in which ethnic variables have been specified and operationalized, delineating the assumptions and trade-offs underlying their use. Next, we describe an institutional approach to the study of ethnic politics, which focuses on the rules and procedures for differentiating ethnic categories. We propose some new indices based on this latter approach that might be developed and used in future research. Subsequently, we analyze the relationship between each of these approaches and patterns of ethnic political competition in a set of six country cases, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses, as well as theoretical links between them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Calculated according to the formula \( \left[ {{\text{ELF}} = {1} - \sum\nolimits_{{i = 1}}^n {s_i^2} } \right] \), where s i indicates the population share represented by each group, i = (1,…, n).

It is important to note here that while the measure of cross-cuttingness is primarily based on counts of ethnic groups and we therefore classify it within the demographic family of approaches, in so far as it also includes data on income differences between groups and geographic concentration, the index builds on and could also be potentially grouped with the hybrid approaches that we will discuss later in this article.

Habyarimana et al. (2009: 156) provide a useful delineation of the mechanisms by which ethnic demography has been hypothesized to lead to reduced provision of a range of different public goods. It is notable that two of the three families of mechanisms that they identify—preferences and technology—are closely linked to competition between ethnic groups. For example, the absence of other-regarding or shared preferences over outcomes as well as the process is hypothesized to generate competition between members of different ethnic groups. A similar competitive dynamic can be seen to underlie the technology mechanism whereby individuals from different ethnic groups are hypothesized to be less likely to function, understand or think they understand, engage and track down each other.

Of course, such approaches are also used to study the individual-level causes and consequences of ethnic identification, but this article focuses on aggregate or macrolevel relations.

For example, there is considerable variation on questions about national identity depending on whether they are structured in terms of eliciting “closeness,” “belonging,” or “pride.” In general, far more respondents claimed that they felt “close” to their country (International Social Survey 1995) as compared to “belonging” to it (European Values Study 1990). In Hungary, for instance, 96 % said they felt close to their nation (ISS 1995) but only 63 % felt that they belonged to it (EVS 1990). Even within the same survey, for example, the European Values Study of 1990, there are remarkable differences in the proportion of people who said they were proud of their nationality and those that indicated a strong sense of identification with their country. In the USA, 98 % of people said they were proud to be American, but only 58 % said they felt a sense of belonging to the USA. The difference is even more conspicuous for a country such as Latvia where 92 % of respondents indicate pride in their country but only 15 % felt that they belonged to it. It is far from clear which of these is the best measure of national identity and depending on which one you use, countries line up very differently.

For example, General Inquirer, Diction 5.0, VBPro, Yoshikoder and Wordstat.

The first measure is an extension of the Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2005) and Esteban and Ray (1994) polarization indices, discussed in the section on “Demographic approaches,” and captures the extent to which economic resources, measured by the household assets of respondents, and social resources, measured by respondents’ years of education are clustered by ethnic group. Secondly, she introduces a two-group measure called HI (Horizontal Inequality), which ranges from 0 (perfect equality in resources between groups) to 1 (one group has all assets/education).

We seek to identify particular cleavages and to code censuses in earlier decades, and therefore, we could not simply use Morning’s data for our purposes.

In order to determine if institutions codified ethnicity, we attempted, wherever possible, to obtain actual primary documents. As a second step, we tried to attain authoritative secondary sources based on primary analyses of relevant documents and data and/or by contacting foreign nationals, diplomatic representatives, and scholarly authorities.

While religious and linguistic categories are largely self-explanatory, we classify race categories as those ethnic categories explicitly described in terms of physical characteristics (for example, color) and/or referred to as “race” by given state institutions; caste categories as those linked to a codified caste system, recognized from religious scripture or those referred to as “caste” by state institutions; indigenous categories as those groups referred to as “indigenous,” “original inhabitant,” or “natives,” by institutions, except when the group(s) are also commonly linked to one of the other categories already described (for example, “Natives” are considered a race group in South Africa), and ethnic/other is a residual category used when state institutions refer to specific ethnic or “tribal” groups that could not be classified in one of the abovementioned categories (for instance, an ethnic group that is not distinguished by use of a single language). For each category, we employed standardized sourcebooks to identify any evidence that the second largest group constituted at least 1 % of the population at any moment in time and, if not, we ignored that category for the purposes of our analysis. In other words, if more than 99 % of a country belonged to a particular religious faith, we did not investigate and do not report data on institutionalized ethnicity in terms of religion because it is not a potential boundary between substantially large groups of citizens.

While the question of the “agency” of the adivsasis in the Maoist insurgency is a deeply contested one (Nigam 2010); this is a conflict that is at the very least fought in the name of the indigenous people and the combatants are drawn overwhelmingly from indigenous groups.

Even though there were physiological stereotypes associated with the Hutus and Tutsis, the task of distinguishing individuals from the two communities was complicated by the high rates of intermarriage. The practice of marking the bearer’s ethnic origin on official identity documents greatly facilitated the conduct of the genocide by making it “easy to identify Tutsi” (Longman 2001: 355). Longman writes that “Since every Rwandan was required to carry an identity card, people who guarded barricades demanded that everyone show their cards before being allowed to pass. Those with “Tutsi” marked on their cards were generally killed on the spot” (Longman 2001: 355).

The MAR dataset also identifies a “moderate” risk for rebellion against the state by the Amazonian Indians.

References

Abdelal R, McDermott R, et al. Identity as a variable. Perspect Polit. 2006;4(4):695–711.

Adcock R, Collier D. Measurement validity: a shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2001;95(3):529–46.

Alesina A, Baqir R, et al. Public goods and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1999;114(4):1243–84.

Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, et al. Fractionalization. J Econ Growth. 2003;8:155–94.

Annett A. Social fractionalization, political instability, and the size of government. IMF Staff Pap. 2001;48(3):561–92.

Appadurai A. Number in the colonial imagination. In: Breckenridge CA, Veer Pvander, editors. Orientalism and the postcolonial predicament. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1993.

Bailey S, Telles EE. Multiracial vs. collective black categories: census classification debates in Brazil. Ethnicities. 2006;6(1):74–101.

Baldwin K, Huber J. Economic versus cultural differences: forms of ethnic diversity and public goods provision. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(4):644.

Barth F. Ethnic groups and boundaries. Boston: Little, Brown; 1969.

Birnir J. Divergence in diversity? The dissimilar effects of cleavages on electoral politics in new democracies. Am J Polit Sci. 2007;51(3):602–19.

Bossert W, D'Ambrosio C, et al. A generalized index of fractionalization. Economica. 2010;78(312):723–750

Brady H, Kaplan CS. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic identity. In Herrera et al, editors Measuring identity: a guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Brass PR. The Punjab crisis and the unity of India. In: Kohli A, editor. India's democracy: an analysis of changing state-society relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1990.

Brass PR. Language, religion, and politics in North India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1974.

Brewer MB, Kramer RM. Choice behavior in social dilemmas: effects of social identity, group size, and decision framing. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1986;50(3):543–9.

Brubaker R. Ethnicity without groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004.

Cederman L-E, Girardin L. Beyond fractionalization: mapping ethnicity onto nationalist insurgencies. Am Polit Sci Rev 2007;101(1):173–85.

Cederman L-E, Min B, Wimmer A. Ethnic power relations dataset. http://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/11796 UNF:5:k4xxXC2ASI204QZ4jqvUrQ== V1(May 2, 2009); 2009.

Cederman L-E, Weidman N, Gleditsch K. Horizontal inequalities and ethnonationalist civil war: a global comparison. Am Polit Sci Rev 2011;105(3): 478–95.

Chandra K. Why ethnic parties succeed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Chandra K. What is Ethnicity and does it matter? Annu Rev Pol Sci. 2006;9:397–424

Chandra K. Why voters in patronage-democracies split their tickets: strategic voting for ethnic parties in patronage-democracies. Elect Stud. 2009;28:21–32

Chandra K, Wilkinson S. Measuring the effect of “ethnicity”. Comp Polit Stud. 2008;41(4–5):515–63.

Dallaire R. Shake hands with the devil: the failure of humanity in Rwanda. New York: Carroll & Graf; 2005.

Destexhe A. Rwanda and genocide in the twentieth century. London: Pluto Press; 1995.

Dirks N. Castes of mind: colonialism and the making of modern India. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2001.

Dudley-Jenkins L. Identity and identification in India: defining the disadvantaged. Hove: Psychology Press; 2003.

Dunning T. Do quotas promote ethnic solidarity? Field and natural experimental evidence from India. New Haven: Yale University; 2010.

Dunning T, Harrison L. Cross-cutting cleavages and ethnic voting: an experimental study of cousinage in Mali. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(1):21–39.

Easterly W, Levine R. Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Q J Econ. 1997;112:1202–50.

Esteban J-M, Ray D. On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica. 1994;62(4):819–51

Fearon J. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J Econ Growth. 2003;8:195–222.

Fish MS, Brooks RS. Does diversity hurt democracy? J Democr. 2004;15(1):154–66.

Fox RG. Lions of the Punjab: culture in the making. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985.

Galvan D. Joking kinship as a syncretic institution. Cahiers d'Etudes Afr. 2006;XLVI(4):183–4.

Gibson JL, Gouws A. Overcoming intolerance in South Africa: experiments in democratic persuasion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Gilens M. Why Americans hate welfare: race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.

Gourevitch P. We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families: stories from Rwanda. New York, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; 1998.

Gurr TR. People versus states: minorities at risk in the new century. Africa Today. Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press; 2000.

Habyarimana J, Humphreys M, Posner D, Weinstein J. Coethnicity: diversity and the dilemmas of collective action. Russell Sage Foundation; 2009.

Hechter M. Group formation and the cultural division of labour. Am J Sociol. 1978;84:293–318.

Helmuth C. Culture and customs of Costa Rica. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2000.

Herath R. Sri Lankan ethnic crisis: towards a resolution. Trafford on Demand Pub. 2002.

Horowitz D. Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985.

Jensen C, Skaaning SE. Democracy, ethnic fractionalization, and the politics of social spending. Department of Political Science, Aarhus University. 2010.

Kabashima I, et al. Neural correlates of attitude change following positive and negative advertisements. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:6.

Kalyvas SN. The ontology of political violence: action and identity in civil wars. Perspect Polit. 2003;1:475–94.

Kertzer DI, Arel D, editors. Census and identity: the politics of race, ethnicity, and language in national censuses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Kohli A, Basu A. Community conflicts and the state in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Laitin D. Hegemony and culture: politics and religious change among the Yoruba. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986.

Laitin D, Fearon J. Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2003;97(1):75–90.

Lamont M, Molnár V. The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annu Rev Sociol 2002;28:167–95.

LaPorta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny R. The quality of government. J Law Econ Organ. 1999;15:222–79.

Lee T. Between social theory and social science practice: toward a new approach to the survey measurement of “race”. In: Abdelal R, Herrera YM, Johnston AI, McDermott R, editors. Measuring Identity: A Guide for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Lieberman ES. Boundaries of contagion: how ethnic politics have shaped government responses to AIDS. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2009.

Longman T. Identity cards, ethnic self-perception and genocide in Rwanda. In: Caplan J and Torpey J, editors. Documenting individual identity: the development of state practices in the modern world. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2001.

Mahapatra D. SC had hinted at possible caste war. The Times of India 2007.

Mamdani M. When victims become killers: colonialism, nativism, and the genocide in Rwanda. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2001.

Marx A. Making race and nation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

Matuszeski J, Schneider F. Patterns of ethnic group segregation and civil conflict. Harvard University, Working Paper; 2006.

Mendelberg T. The race card: campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2001.

Miguel E, Gugerty MK. Ethnic diversity, social sanctions, and public goods in Kenya. J Public Econ. 2005;89(11–12):2325–68.

Misra S. A narrative of communal politics: Uttar Pradesh, 1937–39. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001.

Montalvo JG, Reynal-Querol M. Ethnic polarization, potential conflict and civil war. Am Econ Rev. 2005;95(3):796–816.

Morning A. Ethnic classification in global perspective: a cross-national survey of the 2000 Census round. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2008;27:239–72.

Mozaffar S, Scarritt JR, et al. Electoral institutions, ethnopolitical cleavages, and party systems in Africa’s emerging democracies. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2003;97:379–90.

Nigam, A. The rumor of Maoism. Seminar. 2010;607.

Nobles M. Shades of citizenship: race and the census in modern politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2000.

Ostby G. Polarization, horizontal inequalities and violent civil conflict. J Peace Res. 2008;45(2):143–62.

Petersen RD. Understanding ethnic violence: fear, hatred, and resentment in twentieth-century Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Posner D. The colonial origins of ethnic cleavages: the case of linguistic divisions in Zambia. Comp Polit. 2003;35(2):127–46.

Posner D. Measuring ethnic fractionalization in Africa. Am J Polit Sci. 2004;48(4):849–63.

Purcell T, Sawyers K. Democracy and ethnic conflict: blacks in Costa Rica. Ethnic Racial Stud. 1993;16:298–322.

Rabushka A, Shepsle KA. Politics in plural societies: a theory of democratic instability. New York: Longman; 1972.

Rajasingham KT. Sri Lanka: the untold story. Asia Times Online. 2001.

Reynal-Querol M. Ethnicity, political systems and civil wars. J Confl Resolut. 2002;46(1):29–54.

Roeder PG. Ethnolinguistic Fractionalization (ELF) indices, 1961 and 1985. 2001.

Sambanis N. Do ethnic and non-ethnic civil wars have the same causes?: a theoretical and empirical inquiry (part I). Washington: World Bank; 2001.

Selway JS. The measurement of cross-cutting cleavages and other multidimensional cleavage structures. Polit Anal. 2011;19(1):48–65.

Simmel G. Conflict and the web of group-affiliations. Gelncoe: Free Press; 1955.

Smith AD. Ethnicity and nationalism. Leiden: E.J. Brill; 1992.

Sowell T. Affirmative action around the world: an empirical study. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2004.

Sylvan DA, Metskas AK. Trade-offs in measuring identities: a comparison of five approaches. In: Abdelal R, Herrera YM, Johnston AI, McDermott R, editors. Measuring Identity: A Guide for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. The psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson Hall; 1986.

Telles EE. Race in another America: the significance of skin color in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2004.

Tilly C. Identities, boundaries, and social ties. Boulder: Paradigm; 2005.

Torpey J. The invention of the passport. Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pressp; 2000.

Turra C, Venturi G, editors. Racismo cordial. São Paulo: Editora Ática; 1995.

Uvin P. On counting, categorizing, and violence in Burundi and Rwanda. In: Kertzer DI, Arel D, editors. Census and identity: the politics of race, ethnicity, and language in national censuses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. p. 148–75.

VanCott DL. From movements to parties in Latin America: the evolution of ethnic politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Varshney A. Ethnic conflict and civic life: Hindus and Muslims in India. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2002.

Varshney A. Nationalism, ethnic conflict, and rationality. Perspect Polit. 2003;1:85–99.

Westen D, Blagov PS, et al. Neural bases of motivated reasoning: an fMRI study of emotional constraints on partisan political judgment in the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(11):1947–58.

Wilkinson S. Votes and violence: electoral competition and ethnic riots in India. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Wilkinson S. Which group identities lead to most violence? Evidence from India. In: Kalyvas SN, Shapiro I, Masoud T, editors. Order, conflict, and violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Wimmer A, Cederman L-E, Min, B. Ethnic politics and armed conflict: a configurational analysis of a new global data set. Am Sociol Rev. 2009;74(April):316–37.

Witte EH, Davis JH. Understanding group behavior, Vol. 2: small group processes and interpersonal relations. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996.

Yadav Y, Kumar S. Poor man’s rainbow over UP. New Delhi: Indian Express; 2007.

Yashar DJ. Contesting citizenship in Latin America: the rise of indigenous movements and the postliberal challenge. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Young C. Nationalism, ethnicity, and class in Africa: a retrospective. Cahiers D'Etudes Afr. 1986;26(3):421–95.

Young C. The African colonial state in comparative perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1994.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author names are listed alphabetically; both authors contributed equally to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lieberman, E.S., Singh, P. Conceptualizing and Measuring Ethnic Politics: An Institutional Complement to Demographic, Behavioral, and Cognitive Approaches. St Comp Int Dev 47, 255–286 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-012-9100-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-012-9100-0