Abstract

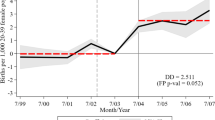

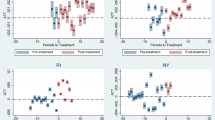

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), implemented in August 1993, grants job-protected leave to any employee satisfying the eligibility criteria. One of the provisions of the FMLA is to allow women to stay at home for a maximum period of 12 weeks to give care to the newborn. The effect of this legislation on the fertility response of eligible women has received little attention by researchers. This study analyzes whether the FMLA has influenced birth outcomes in the U.S. Specifically, I evaluate the effect of the FMLA by comparing the changes in the birth hazard profiles of women who became eligible for FMLA benefits such as maternity leave, to the changes in the control group who were not eligible for such leave. Using a discrete-time hazard model, results from the difference-in-differences estimation indicate that eligible women increase the probability of having a first and second birth by about 1.5 and 0.6 % per annum, respectively. Compared to other women, eligible women are giving birth to the first child a year earlier and about 8.5 months earlier for the second child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although it is a federal policy, knowledge of the FMLA is still not as widespread since only 58.2% of employees at covered worksites have any knowledge of FMLA (Department of Labor 2007).

The United Nations watchdog on labor issues, the International Labor Organization (ILO) prescribes a minimum of 14 weeks maternity leave along with some cash benefit (International Labor Organization 2000).

The states are California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Washington, Wisconsin and Vermont. Information obtained from Waldfogel (1999).

Averett and Whittington (2001) investigate the impact of maternity leave on influencing births during the period 1985 to 1992, which was a period before the FMLA was introduced.

Less than 25% of the contiguous states of the U.S. had any state legislation establishing job-protected maternity leave.

See U.S. Department of Labor website (http://www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/CONSADReport.pdf, accessed May 14, 2012) for a detailed explanation of what constitutes a covered employer.

Under the FMLA, if two spouses are employed by the same employer, then the combined leave allowed is 12 weeks.

Waldfogel (1999) noted that the NLSY data as being a potentially good source of information in investigating the FMLA’s impact on leave coverage. At the time of her research, the span of the data was too short to carry out any meaningful investigation.

Ineligible women are those who do not satisfy all the eligibility criteria and who have worked some positive number of hours in each of the years during the survey period 1989–2010. Therefore, women who never worked in any year during this time period are excluded.

I also cluster at the state level. Later, I show the results are robust to this specification.

The authors estimated the effect of the “desired number of children” on the probability of being in a maternity leave job. They found that the coefficient on “desired number of children” was negative and insignificant. A statistically insignificant result indicates little/no evidence of selection bias caused by women sorting into firms offering maternity leave because they want to have children.

Each wave of the NLSY79 asks respondents whether they are employed at a job that offers job-protected maternity leave. Job-protected maternity leave guarantees an individual the right to return to work after being granted leave from the same employer conditional upon the employee spending no more than the maximum allowable leave. As mentioned earlier, varying degrees of job-protected maternity leave existed in states before the FMLA was implemented.

There is also a selection bias whereby women who desire children may choose to not work. In which case, the probability of giving a birth increases for these ineligible women. By including women who are not working, I am actually underestimating the impact of the policy. Also, women in larger firms with longer tenure and more work hours may be more committed to career and may be less likely to have children or more likely to delay. This would bias against finding fertility effects of FMLA on eligible women.

Indeed, in addition to childcare, employer-side characteristics would be correlated with employment eligibility. As part of the empirical analysis, I consider firm size (as well as income levels) in the investigation of the impact of FMLA eligibility on birth outcomes. In the interest of space, these regression results were not reported.

In 2007, there were 33,740 private schools in the US. See the U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics, Private School Universe Survey 2007–2008 available at http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d09/tables/dt09_058.asp (accessed October 2, 2010). In 2002, the total number of firms as reported by the Census Bureau was 22,974,655. See the U.S. Census Bureau: State and Country Quick Facts available at http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html (accessed October 2, 2010).

For example, in 2007, only 8 % of private sector workers could access paid family leave benefits. See U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States at http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/sp/ebsm0006.pdf (accessed September 21, 2010).

I also ran the model using completed fertility as the dependent variable. The results were qualitatively similar.

See Section 2 for a definition of a covered employer and how this relates to a woman being eligible for FMLA benefits. I also present models where the sample is disaggregated according to firm size. For firms with less than 50 employees, the coefficient of interest was not significantly different from zero. This result is not surprising because firms in this size category (with a few exceptions as noted in Section 2) by definition are not covered institutions, thus making the employees ineligible for FMLA benefits.

Therefore, the more educated are better able to utilize the leave benefits of the FMLA because of better knowledge about policy. Recall, only 58.2% of employees at covered worksites had any knowledge of FMLA (Department of Labor 2007). Another reason why the FMLA has been ineffective in for other groups such as those in marginal employment can be explained by the fact that the majority of these individuals are not covered under the current FMLA eligibility criteria. That is, they are employed in institutions with less than 50 employees. See further details in the section on Sensitivity Analysis.

In addition, I run regressions based on the size of the firm and find that the effect of the interaction term (FMLA*eligibility) is significant at the 10% level for large firms (those with at least 500 employees).

The p-value for the Likelihood Ratio test on the difference between the placebo and the true results is zero in both panels. In addition, the AIC/BIC provide strong support for the true model.

I also run the same regression, this time including a quadratic trend and interacting with eligibility status. The results (not shown) are also robust to this specification.

Data source: http://www.census.gov/epcd/www/smallbus.html (accessed January 25, 2011).

Inspection of the data reveals positive skewness in the outcomes used in this analysis.

See the 2011 Statistical Abstract of U.S. Census Bureau at http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/births_deaths_marriages_divorces.html (Accessed July 19, 2011).

References

Allison PD (1984) Event History Analysis. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Averett SL, Whittington LA (2001) Does maternity leave induce births?”. South Econ J 68(2):403–417

Baker M, Milligan K (2008a) “How does job-protected maternity leave affect mothers’ employment?”. J Labor Econ 26(4):655–691

Baker M, Milligan K (2008b) “Maternal employment breastfeeding and health: evidence from maternity leave mandates”. J Health Econ 27:871–887

Baum CL (2003) The effect of state maternity leave legislation and the 1993 family and medical leave act on employment and wages. Labour Econ 10(5):573–596

Berger LM, Waldfogel J (2004) Maternity leave and the employment of new mothers in the united states. J Popul Econ 17:331–349

Berger LM, Hill J, Waldfogel J (2005) “Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. Econ J 115(501):F29–F47

Brown, Heidi. 2009, May 04. “U.S. Maternity Leave benefits are still dismal.” Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2009/05/04/maternity-leave-laws-forbes-woman-wellbeing-pregnancy.html (Accessed July 19, 2011).

Buttner T, Lutz W (1990) Estimating fertility responses to policy measures in the German Democratic Republic. Popul Dev Rev 16(3):539–555

Department of Labor. 2007. Family and Medical Leave Act Regulations: A Report on the Department of Labor’s Request for Information. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. http://www.dol.gov/whd/FMLA2007Report/2007FinalReport.pdf (Accessed March 28, 2010).

Folbre, Nancy. 2010, January 25. “Family Leave: Right or Privilege?” The New York Times. http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/25/family-leaves-right-or-privilege/ (Accessed July 19, 2011).

Gauthier AH (2007) The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Popul Res Policy Rev 26(3):323–346

Gauthier HA, Hatzius J (1997) Family benefits and fertility: an econometric analysis. Popul Stud 51(3):295–306

Han WJ, Waldfogel J (2003) The impact of recent parental leave legislation on parent’s leave-taking. Demography 40(1):191–200

Han W, Ruhm C, Waldfogel J (2007) Parental leave policies and parents’ employment and leave-taking”. NBER Work Pap Ser 13697:1–47

Hoem JM (1993) Public policy as the fuel of fertility: effects of a policy reform on the pace of childbearing in sweden in the 1980s. Acta Sociol 36(1):19–31

Hoem, J.M., A Prskawetz and G. Neyer. 2001. “Autonomy or Conservative Adjustment? The Effect of Public Policies and Educational Attainment on Third Births in Austria.” Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) Working Paper, WP 2001–016.

Hyatt DE, Milne WJ (1991) “Can public policy affect fertility?”. Can Public Policy 17(1):77–85

Ife, Holly, and Jen Kelly. 2008, May 14. “Call for Universal Maternity Leave.” Herald Sun. http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/call-for-universal-maternity-leave/story-e6frf7l6-1111116328669 (Accessed July 19, 2011).

International Labor Organization. 2000. Maternity Protection Convention (Revised) C183. http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C183 (Accessed October 1, 2010).

Kamerman, Sheila and Shirley Gatenio. 2002. “Mother’s Day: More than Candy and Flowers, Working Parents Need Paid Time Off.” Spring Issue Brief. Columbia, NY: The Clearinghouse on International Developments in Child, Youth and Family Policies. http://www.childpolicyintl.org/issuebrief/issuebrief5.pdf (Accessed May 5, 2010).

Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481

Klerman JA, Leibowitz A (1998) “FMLA and the Labor Supply of New Mothers: Evidence from the June CPS”. Unpublished paper prepared for presentation at the Population of America Annual Meetings. IL, Chicago

Klerman JA, Leibowitz A (1999) Job continuity among new mothers. Demography 36(2):145–155

Lalive R, Zweimüller J (2009) How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? evidence from two natural experiments. Q J Econ 124(3):1363–1402

Milligan, Kevin. 2002. “Quebec’s baby bonus: Can public policy raise fertility?” Backgrounder. C.D. Howe Institute. http://www.cdhowe.org/pdf/Milligan_Backgrounder (accessed May 5, 2010).

Noble, Barbara Presley. 1993, August 1. Saltzman, Jonathan. 2010, August 9. “At Work; Interpreting the Family Leave Act.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/01/business/at-work-interpreting-the-family-leave-act.html?src=pm (Accessed July 19, 2011).

Ross KE (1998) Labor pains: the effect of the family and medical leave act on the return to paid work after childbirth. Focus 20(1):34–36

Rossin M (2011) The effects of maternity leave on children’s birth and infant health outcomes in the United States. J Health Econ 30(2):221–239

Ruhm CJ (1997) Policy watch: the family and medical leave act. J Econ Perspect 11(3):175–186

Ruhm CJ (1998) The economic consequences of parental leave mandates: lessons from europe. Q J Econ 113(1):285–318

Ruhm CJ (2000) Parental leave and child health. J Health Econ 19(6):931–960

Saltzman, Jonathan. 2010, August 9. “Unpaid Maternity Leave is Capped at Eight Weeks.” The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/local/breaking_news/2010/08/by_jonathan_sal_6.html (Accessed July 19, 2011).

Tanaka S (2005) Parental leave and child health across OECD countries. Econ J 115(502):F7–F28

U.S. Census Bureau, 2012. Statistical Abstract of the United States 2012, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/ (Accessed 29 Apr 2014).

Waldfogel J (1998) The family gap for young women in the united states and britain: can maternity leave make a difference?”. J Labor Econ 16(3):505–546

Waldfogel J (1999) The impact of the family and medical leave act. J Policy Anal Manag 18(2):281–302

Winegarden CR, Bracy PM (1995) Demographic consequences of maternal-leave programs in industrial countries: evidence from fixed-effects models. South Econ J 61(4):1020–1035

Acknowledgments

I thank Naci Mocan, Patricia Anderson, Lucie Schmidt and the seminar participants of the 2010 Southern Economic Association Conference and the Louisiana State University Economics Department Brown-bag seminar series for helpful discussions and suggestions. Two anonymous referees provided helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cannonier, C. Does the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) Increase Fertility Behavior?. J Labor Res 35, 105–132 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9181-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9181-9

Keywords

- Family and medical leave act

- FMLA

- Fertility

- Births

- Hazard models

- Maternity leave

- Difference-in-differences