Abstract

Background

Engagement in leisure has a wide range of beneficial health effects. Yet, this evidence is derived from between-person methods that do not examine the momentary within-person processes theorized to explain leisure’s benefits.

Purpose

This study examined momentary relationships between leisure and health and well-being in daily life.

Methods

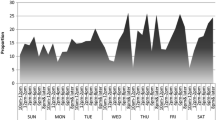

A community sample (n = 115) completed ecological momentary assessments six times a day for three consecutive days. At each measurement, participants indicated if they were engaging in leisure and reported on their mood, interest/boredom, and stress levels. Next, participants collected a saliva sample for cortisol analyses. Heart rate was assessed throughout the study.

Results

Multilevel models revealed that participants had more positive and less negative mood, more interest, less stress, and lower heart rate when engaging in leisure than when not.

Conclusions

Results suggest multiple mechanisms explaining leisure’s effectiveness, which can inform leisure-based interventions to improve health and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Iso-Ahola SE. Basic dimensions of definitions of leisure. J Leis Res. 1979; 11: 28-39.

Manfredo MJ, Driver BL, Tarrant MA. Measuring leisure motivation: A meta-analysis of the recreation experience preference scales. J Leis Res. 1996; 28: 188-213.

Dupuis SL, Smale BJ. An examination of relationship between psychological well-being and depression and leisure activity participation among older adults. Soc Leisure. 1995; 18: 67-92.

Lawton MP. Personality and affective correlates of leisure activity participation by older people. J Leis Res. 1994; 26: 138-157.

Siegenthaler KL, Vaughan J. Older women in retirement communities: Perceptions of recreation and leisure. Leis Sci. 1998; 20: 53-66.

Herzog A, Franks MM, Markus HR, Holmberg. Activities and well-being in older age: Effects of self-concept and educational attainment. Psychol Aging. 1998; 13: 179-185.

Lee CT, Yeh CJ, Lee MC, et al. Leisure activity, mobility limitation and stress as modifiable risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly: Results of a national longitudinal study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012; 54: e221-e229.

Caltabiano ML. Measuring the similarity among leisure activities based on a perceived stress-reduction benefit. Leis Stud. 1994; 13: 17-31.

Dewe P, Trenberth L. An exploration of the role of leisure in coping with work related stress using sequential tree analysis. Bri J Guid Counc. 2005; 33: 101-116.

Iwasaki Y. Counteracting stress through leisure coping: A prospective health study. Psychol Health Med. 2006; 11: 209-220.

Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Kivimaki M, Marmot M, Smith GD. Walking pace, leisure time physical activity, and resting heart rate in relation to disease-specific mortality in London: 40 years follow-up of the original Whitehall study. An update of our work with professor Jerry N. Morris (1910–2009). Ann Epidemiol. 2010; 20: 661-669.

Sofi F, Capalbo A, Marcucci R, et al. Leisure time but not occupational physical activity significantly affects cardiovascular risk factors in an adult population. Eur J Clin Investig. 2007; 37: 947-953.

Zawadzki MJ, Smyth JM, Merritt MM, Gerin W. Absorption in self-selected activities is associated with lower ambulatory blood pressure but not for high trait ruminators. Am J Hypertens. 2013; 26: 1273-1279.

Fletcher GF, Balady G, Blair SN, et al. Statement on exercise for health professionals by the committee on exercise and cardiac rehabilitation of the council on clinical cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996; 94: 857-862.

Achten J, Jeukendrup AE. Heart rate monitoring. Sports Med. 2003; 33: 517-538.

Arai Y, Saul JP, Albrecht P, et al. Modulation of cardiac autonomic activity during and immediately after exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989; 256: H132-H141.

Kramer GH. The ecological fallacy revisited: Aggregate-versus individual-level findings on economics and elections, and sociotropic voting. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1983; 77: 92-111.

Portnov BA, Dubnov J, Barchana M. On ecological fallacy, assessment errors stemming from misguided variable selection, and the effect of aggregation on the outcome of epidemiological study. J Exp Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007; 17: 106-121.

Molenaar PC, Campbell CG. The new person-specific paradigm in psychology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009; 18: 112-117.

Houtveen JH, Oei NYL. Recall bias in reporting medically unexplained symptoms comes from semantic memory. J Psychosom Res. 2007; 62: 277-282.

Robinson MD, Clore GL. Episodic and semantic knowledge in emotional self-report: Evidence for two judgment processes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002; 83: 198-215.

Smyth JM, Stone AA. Ecological momentary assessment research in behavioral medicine. J Happiness Stud. 2003; 4: 35-52.

Smyth JM, Heron KE. Health psychology. In: Mehl MR, Conner TS, eds. Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. New York: The Guilford Press; 2012: 569-584.

Schneider IE, Iwasaki Y. Reflections on leisure, stress, and coping research. Leis Sci. 2003; 25: 301-305.

Murray G, Allen NB, Trinder J. Mood and the circadian system: Investigation of a circadian component in positive affect. Chronobiol Int. 2002; 19: 1151-1169.

Stone A, Smyth JM, Pickering T, Schwartz J. Daily mood variability: Form of diurnal patterns and determinants of diurnal patterns. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1996; 26: 1286-1305.

Watson D. Intraindividual and interindividual analyses of positive and negative affect: Their relation to health complaints, perceived stress, and daily activities. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54: 1020-1030.

Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: A functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001; 16: 457-469.

Weissinger E. Effects of boredom on self-reported health. Soc Leisure. 1995; 18: 21-32.

Abramson EE, Stinson SG. Boredom and eating in obese and non-obese individuals. Addict Behav. 1977; 2: 181-185.

Koball AM, Meers MR, Storfer-Isser A, Domoff SE, Musher-Eizenman DR. Eating when bored: Revision of the Emotional Eating Scale with a focus on boredom. Health Psychol. 2012; 31: 521-524.

Caldwell LL, Smith EA. Health behaviors of leisure alienated youth. Soc Leisure. 1995; 18: 143-156.

Gordon WR, Caltabiano ML. Urban-rural differences in adolescent self-esteem, leisure boredom, and sensation seeking as predictors of leisure-time usage and satisfaction. Adolescence. 1996; 31: 883-901.

Smyth J, Ockenfels MC, Porter L, Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH, Stone AA. Stressors and mood measured on a momentary basis are associated with salivary cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998; 23: 353-370.

DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988; 54: 486-495.

Jones F, O’Connor DB, Conner M, McMillan B, Ferguson E. Impact of daily mood, work hours, and iso-strain variables on self-reported health behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2007; 92: 1731-1740.

Greenland P, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, et al. Resting heart rate is a risk factor for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: The Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Am J Epidemiol. 1999; 149: 853-862.

Palatini P, Thijs L, Staessen JA, et al. Predictice value of clinic and ambulatory heart rate for mortality in elderly subjective with systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162: 2313-2321.

Giacobbi PR, Hausenblas HA, Frye N. A naturalistic assessment of the relationship between personality, daily life events, leisure-time exercise, and mood. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2005; 6: 67-81.

Hopkins ME, Davis FC, Vantieghem MR, Whalen PJ, Bucci DJ. Differential effects of acute and regular physical exercise on cognition and affect. Neuroscience. 2012; 215: 59-68.

Lane AM, Lovejoy DJ. The effects of exercise on mood changes: The moderating effect of depressed mood. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2001; 41: 539-545.

Barrett LF, Barrett DJ. An introduction to computerized experience sampling in psychology. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2001; 19: 175-185.

Dunton GF, Kawabata K, Intille S, Wolch J, Pentz MA. Assessing the social and physical contexts of children’s leisure-time physical activity: An ecological momentary assessment study. Am J Health Promot. 2012; 26: 135-142.

Iwasaki Y, Mannell RC. Hierarchical dimensions of leisure stress coping. Leis Sci. 2000; 22: 163-181.

Atienza AA, Collins R, King AC. The mediating effects of situational control on social support and mood following a stressor: A prospective study of dementia caregivers in their natural environments. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001; 56: S129-S139.

King AC, Oka RK, Young DR. Ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate responses to the stress of work and caregiving in older women. J Gerontol. 1994; 49: M239-M245.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24: 385-396.

Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, eds. The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988: 31-67.

Barreira TV, Kang M, Caputo JL, Farley RS, Renfrow MS. Validation of the Actiheart monitor for the measurement of physical activity. Int J Exerc Sci. 2009; 2: 60-71.

Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol. 1998; 17: 6-16.

Gil KM, Carson JW, Porter LS, Scipio C, Bediako SM, Orringer E. Daily mood and stress predict pain, health care use, and work activity in African American adults with sickle-cell disease. Health Psychol. 2004; 23: 267-274.

Benson H, Klipper MZ. The relaxation response. New York: Harper Collins; 1992.

Saxbe DE. A field (researcher’s) guide to cortisol: Tracking HPA axis functioning in everyday life. Health Psychol Rev. 2008; 2: 163-190.

Kleiber DA. Leisure experience and human development: A dialectical interpretation. New York: Basic Books. Inc; 1999.

Coleman D, Iso-Ahola SE. Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. J Leis Res. 1993; 25: 111-128.

Barnett LA. Measuring the ABCs of leisure experience: Awareness, boredom, challenge, distress. Leis Sci. 2005; 27: 131-155.

Caldwell LL, Smith EA, Weissinger E. Development of a leisure experience battery for adolescents: Parsimony, stability, and validity. J Leis Res. 1992; 24: 361-376.

Ebrahim S, Smith GD. Lowering blood pressure: A systematic review of sustained effects of non-pharmacological interventions. J Publ Health. 1998; 20: 441-448.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000; 55: 68-78.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J Res Pers. 1985; 19: 109-134.

Melamed S, Meir EI, Samson A. The benefits of personality-leisure congruence: Evidence and implications. J Leis Res. 1995; 27: 25-40.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors, Matthew J. Zawadzki, Joshua M. Smyth, and Heather J. Costigan, have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Adherence Statement

The research was conducted in compliance with the American Medical Association and the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

About this article

Cite this article

Zawadzki, M.J., Smyth, J.M. & Costigan, H.J. Real-Time Associations Between Engaging in Leisure and Daily Health and Well-Being. ann. behav. med. 49, 605–615 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9694-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9694-3