Abstract

Child deprivation has severe short-term as well as life-long consequences for children experiencing it. Using the new child-specific deprivation indicator adopted by the European Union in 2018 and computed from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions dataset, the paper analyses the determinants of child deprivation in 31 European countries. It applies negative binomial multilevel models, which combine household-level and country-level variables. The latter include various macro-level variables that are new to the deprivation literature.

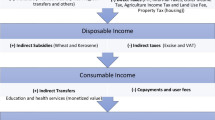

The results show the combined impact of factors related to “household’s longer-term command over resources” and factors explaining “household needs”. Regarding the role of the welfare state and social transfers in child deprivation, the paper highlights the impact of cash benefits, which operates through household income, and of in-kind benefits, which decrease a household’s needs and increase household’s resources. Another important conclusion is that the provision of affordable education reduces child deprivation, as it can mitigate the cost burden faced by parents.

In terms of policy implications, the paper shows the importance of investing in social protection and public services in order to reduce child deprivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Norway could not be included due to the large amount of missing data on child deprivation.

On the importance of the reliability of deprivation indicators, see Nájera Catalán and Gordon (2019).

Both the logarithm and linear forms of the income variable were entered in the regressions. The best regression fit was obtained with the non-logarithm form of the variable.

For Iceland, Serbia and Switzerland, a child is considered to be a migrant if at least one member of its household was born in a country which is neither the country of residence nor an EU country.

In the EU the age of a child is defined between 0 and 17, which is not consistent with the unit of data collection of the child deprivation indicator (age 0–15).

See Čomić (2022).

Using only macro variables, Kenworthy et al., (2011) had paved the way for this, explaining the dispersion of deprivation between countries by the role of macro-economic variables such as GDP, unemployment, inequality and the size of social policy expenditure.

Himself followed by Chzhen (2014).

“COFOG” stands for “Classification of the functions of government”. It was developed by the OECD.

References

Aaberge, R., Langørgen, A., & Lindgren, P. (2017). The distributional impact of public services in European countries. In A. B. Atkinson, A. C. Guio, & E. Marlier (Eds.), Monitoring social inclusion in Europe (pp. 159–188). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Abe, A., & Pantazis, C. (2014). Comparing public perceptions of the necessities of life across two societies: Japan and the United Kingdom. Social Policy and Society, 13(1), 69–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746413000420

Bárcena Martín, E., Blázquez Cuesta, M., Budría, S., & Egido, M., A.I (2017). Child deprivation and social benefits: Europe in cross-national perspective. Socio-Economic Review, 15(4), 717–744

Bárcena-Martín, E., Lacomba, B., Moro-Egido, A. I., & Pérez‐Moreno, S. (2014). Country Differences in Material Deprivation in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(4), 802–820

Berthoud, R., & Bryan, M. (2011). Income, deprivation and poverty: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Social Policy, 40(01), 135–156

Boarini, R., & d’Ercole, M. M. (2006). Measures of material deprivation in OECD countries, Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 37, OECD, Paris

Brady, D., Giesselmann, M., Kohler, U., & Radenacker, A. (2018). How to measure and proxy permanent income: evidence from Germany and the US. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 16, 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-017-9363-9

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The Effects of Poverty on Children. The Future of Children, 7(2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602387

Chzhen, Y. (2014). Child poverty and material deprivation in the European Union during the Great Recession. Innocenti Working Paper, 2014-06, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence, Italy

Chzhen, Y., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). Lone parents, poverty and policy in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(5), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712456578

Čomić, T. (2022). Methods for collecting data on production for own consumption. In P. Lynn, & L. Lybergred Improving the measurement of poverty and social exclusion in Europe: reducing non-sampling errors. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Council of the European Union (2021). Council Recommendation 2021/1004 establishing a European Child Guarantee. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H1004

Davies, R., & Smith, W. (1998). The basic necessities survey: The experience of Action Aid in Vietnam. London: Action Aid

de Graaf-Zijl, M., & Nolan, B. (2011). Household joblessness and its impact on poverty and deprivation in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(5), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928711418854

de Neubourg, C., Bradshaw, J., Chzhen, Y., Main, G., Martorano, B., & Menchini, L. (2012). Child deprivation, multidimensional poverty and monetary poverty in Europe. Innocenti Working Paper, 2012-02, Background paper 2 for Report Card 10, UNICEF Office of Research, Florence, Italy

Diris, R., Vandenbroucke, F., & Verbist, G. (2017). The impact of pensions, transfers and taxes on child poverty in Europe: the role of size, pro-poorness and child orientation. Socio-Economic Review, 15(4), 745–775. https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/MWW045

European Commission. (2013). Investing in Children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage, Commission Recommendation 2013/112/EU. Brussels: European Commission

European Commission. (2019). European system of integrated social protection statistics — ESSPROS Manual and User Guidelines – 2019 Version. Brussels: European Commission

European Commission. (2021). The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=23696&langId=en

European Council (2021a). The Porto Declaration. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/05/08/the-porto-declaration/

European Council (2021b). European Council meeting (24 and 25 June 2021) – Conclusions. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/50763/2425-06-21-euco-conclusions-en.pdf

Figari, F. (2012). Cross-national differences in determinants of multiple deprivation in Europe. Journal of Economic Inequality, 10(3), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-010-9157-9

Fifita, V., Nandy, S., & Gordon, D. (2015). Child Poverty in Tonga. Bristol, UK: University of Bristol

Frazer, H., Guio, A. C., & Marlier, E. (Eds.). (2020). Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee: Final Report. European Commission, Brussels: Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee (FSCG)

Fusco, A., Guio, A. C., & Marlier, E. (2011). Characterising the income poor and the materially deprived in European countries. In A. B. Atkinson, & E. Marlier (Eds.), Income and living conditions in Europe (pp. 132–153). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: https://doi.org/10.2785/53320

Gazareth, P., & Suter, C. (2010). Privation et risque d’appauvrissement en Suisse, 1999–2007. Swiss Journal of Sociology, 36(2), 213–234

Gordon, D. (2010). Methodology for Multidimensional Poverty Measurement in Mexico Using the Concept of Relative Deprivation (in Spanish). In: Boltvinik, J., Chakravarty, S., Foster, J., Gordon, D., Hernández Cid, R., Soto de la Rosa, H. and Mora, M. (coord.), Medición Multidimensional de la Pobreza en México, México, D.F: El Colegio de México and Consejo de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social. 401–497

Gordon, D., Adelman, A., Ashworth, K., Bradshaw, J., Levitas, R., Middleton, S. … Williams, J. (2000). Poverty and social exclusion in Britain. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Gross-Manos, D., & Bradshaw, J. (2022). The Association between the Material Well-Being and the Subjective Well-Being of Children in 35 Countries. Child Indicators Research, 15(1), 1–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09860-x

Guillén-Fernández, Y. B. (2017). Multidimensional poverty measurement from a relative deprivation approach: a comparative study between the United Kingdom and Mexico, PhD dissertation, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. https://www.poverty.ac.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/YB-Guillen-Fernandez_PhD-dissertation-%28UoB%29.pdf

Guio, A. C., Frazer, H., & Marlier, E. (Eds.). (2021). Study on the economic implementing framework of a possible EU Child Guarantee scheme including its financial foundation, Second phase of the Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee (FSCG2): Final Report. Brussels: European Commission. doi: https://doi.org/10.2767/398365

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., & Marlier, E. (2012). Measuring Material Deprivation in the EU. Indicators for the whole Population and Child-Specific Indicators. Eurostat Methodologies and working papers, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. doi: https://doi.org/10.2785/33598

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E., Nájera Catalán, H., & Pomati, M. (2018). Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 11(3), 835–860. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-017-9491-6

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Nájera Catalán, H., & Pomati, M. (2017). Revising the EU material deprivation variables. Eurostat Methodologies and working papers, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Halleröd, B., Larsson, D., Gordon, D., & Ritakallio, V. M. (2006). Relative deprivation: a comparative analysis of Britain, Finland and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(4), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706068272

Kaijage, F., & Tibaijuka, A. (1996). Poverty and social exclusion in Tanzania. Research Series, No.109, ILO, Geneva

Kenworthy, L., Epstein, J., & Duerr, D. (2011). Generous social policy reduces material deprivation. In L. Kenworthyred Progress for the Poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199591527.003.0004

Kim, C., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2018). The Sources of Life Chances: Does Education, Class Category, Occupation, or Short-Term Earnings Predict 20-Year Long-Term Earnings? Sociological Science, 5, 206–233. doi: https://doi.org/10.15195/v5.a9

Kis, B. A., Özdemir, E., & Ward, T. (2015). Micro and macro drivers of material deprivation rates.Social Situation Monitor Research note, No.7/2015

Main, G., & Bradshaw, J. (2014). The necessities of life for children. PSE working paper analysis 6, July

Marx, I., Salanauskaite, L., & Verbist, G. (2013). The paradox of redistribution revisited: and that it may rest in peace?, IZA Discussion Paper, No. 7414, Institute for the Study of Labour, Bonn

Minujin, A., & Shailen, N. (Eds.). (2012). Global child poverty and well-being: Measurement, concepts, policy and action. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781847424822.003.0001

Mtapuri, O. (2011). Developing an asset threshold using the consensual approach: Results from Mashonaland West, Zimbabwe. Journal of International Development, 23(1), 29–41

Nájera Catalán, H. E. (2019). Reliability, Population Classification and Weighting in Multidimensional Poverty Measurement: A Monte Carlo Study. Social Indicators Research, 142(3), 887–910. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1950-z

Nájera Catalán, H. E., & Gordon, D. (2019). The Importance of Reliability and Construct Validity in Multidimensional Poverty Measurement: An Illustration Using the Multidimensional Poverty Index for Latin America (MPI-LA). Journal of Development Studies, 56(9), 1763–1783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1663176

Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2015). Applying the consensual method of estimating poverty in a low income African setting. Social Indicators Research, 124(3), 693–726

Nelson, K. (2012). Counteracting material deprivation: The role of social assistance in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(2), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928711433658

Nolan, B., & Whelan, C. (2011). Poverty and Deprivation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199588435.001.0001

Notten, G., & Guio, A. C. (2021). At the margin: By how much do social transfers reduce material deprivation in Europe. In A. C. Guio, E. Marlier, & B. Nolanred Improving the understanding of poverty and social exclusion in Europe. Luxembourg: Eurostat, Publications Office of the European Union

Notten, G., & Kaplan, J. (2021). Material deprivation – Measuring poverty by counting necessities households cannot afford. Canadian Public Policy, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2020-011

Perry, B. (2002). The mismatch between income measures and direct outcome measures of poverty. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 19, 101–127

Perry, B. (2021). Child Poverty in New Zealand. New Zealand: Ministry of Social Development. Wellington

Saunders, P., & Brown, J. E. (2020). Child Poverty, Deprivation and Well-Being: Evidence for Australia. Child Indicators Research, 13(1), 1–18

Tárki (2011). Child well-being in the European Union – Better monitoring instruments for better policies. Report prepared for the State Secretariat for Social Inclusion of the Ministry of Public Administration and Justice, Budapest

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. Hardmonsworth: Penguin Books

UNICEF and the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty. (2017). A world free from child poverty – a guide to the task to achieve the vision. New York: UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/reports/world-free-child-poverty

Verbunt, P., & Guio, A. C. (2019). Explaining differences within and between countries in the risk of income poverty and severe material deprivation: Comparing single and multilevel analyses. Social Indicators Research, 144(2), 827–868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2021-1

Visser, M., Gesthuizen, M., & Scheepers, P. (2014). The impact of macro-economic circumstances and social protection expenditure on economic deprivation in 25 European countries, 2007–2011. Social Indicators Research, 115(3), 1179–1203. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0259-1

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., & Maître, B. (2004). Understanding the Mismatch between Income Poverty and Deprivation: A Dynamic Comparative Analysis. European Sociological Review, 20(4), 287–302. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3559562

Whelan, C. T., Layte, R., Maître, B., & Nolan, B. (2001). Income, Deprivation, and Economic Strain: An Analysis of the European Community Household Panel. European Sociological Review, 17(4), 357–372. http://www.jstor.org/stable/522899

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2006). Comparing poverty and deprivation dynamics: Issues of reliability and validity. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 4(3), 303–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-005-9017-1

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2007). Income, deprivation and economic stress in the enlarged European Union. Social Indicators Research, 83(2), 309–329. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9051-9

Whelan, C. T., & Maître, B. (2012). Understanding material deprivation: A comparative European analysis. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.05.001

Wright, G. (2008). Findings from the indicators of poverty and social exclusion project: A profile of poverty using the socially perceived necessities approach. Key report 7. Pretoria: Department of Social Development, Republic of South Africa

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Brian Nolan, Jonathan Bradshaw, Elena Bárcena-Martín, Bertrand Maître, Kenneth Nelson and Geranda Notten for valuable discussions. All errors remain strictly the authors’. This work has been supported by the third Network for the analysis of EU-SILC (Net-SILC3), funded by Eurostat (Grant agreement No. 07142.2015.002-2015.694). The European Commission bears no responsibility for the analyses and conclusions, which are solely those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guio, AC., Marlier, E., Vandenbroucke, F. et al. Differences in Child Deprivation Across Europe: The Role of In-Cash and In-Kind Transfers. Child Ind Res 15, 2363–2388 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09948-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09948-y