Abstract

Background

Psychosocial stress is recognized as a risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD). High rates of CHD in African-Americans may be related to psychosocial stress. However, standard cardiac rehabilitation (CR) usually does not include a systematic stress-reduction technique. Previous studies suggest that the Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique may reduce CHD risk factors and clinical events. This pilot study explored the effects of standard CR with and without TM on a measure of CHD in African-American patients.

Methods

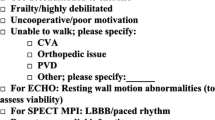

Fifty-six CHD patients were assigned to CR, CR + TM, TM alone, or usual care. Testing was done at baseline and after 12 weeks. The primary outcome was myocardial flow reserve (MFR) assessed by 13N-ammonia positron emission tomography (PET). Secondary outcomes were CHD risk factors. Based on guidelines for analysis of small pilot studies, data were analyzed for effect size (ES).

Results

For 37 patients who completed posttesting, there were MFR improvements in the CR + TM group (+20.7%; ES = 0.64) and the TM group alone (+12.8%; ES = 0.36). By comparison, the CR-alone and usual care groups showed modest changes (+ 5.8%; ES = 0.17 and − 10.3%; ES = − 0.31), respectively. For the combined TM group, MFR increased (+ 14%, ES = 0.56) compared to the combined non-TM group (− 2.0%, ES = − 0.08).

Conclusions

These pilot data suggest that adding the TM technique to standard cardiac rehabilitation or using TM alone may improve the myocardial flow reserve in African-American CHD patients. These results may be applied to the design of controlled clinical trials to definitively test these effects.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration # NCT01810029.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CR:

-

Cardiac rehabilitation

- TM:

-

Transcendental Meditation

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- MFR:

-

Myocardial flow reserve

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending artery

- LCX:

-

Left circumflex artery

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- ES:

-

Effect size

References

Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2007;115(20):2675-82.

Mead H, Ramos C, Grantham SC. Drivers of racial and ethnic disparities in cardiac rehabilitation use: Patient and provider perspectives. Med Care Res Rev 2016;73(3):251-82.

Midence L, Mola A, Terzic CM, et al. Ethnocultural diversity in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2014;34(6):437-44.

Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(1):1-12.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson KW, et al. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: The emerging field of behavioral cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45(5):637-51.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004;364(9438):937-52.

Ford CD, Sims M, Higginbotham JC, et al. Psychosocial factors are associated with blood pressure progression among african americans in the jackson heart study. Am J Hypertens 2016;29(8):913-24.

Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, et al. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation 2005;111(10):1233-41.

Rainforth M, Schneider R, Nidich S, et al. Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep 2007;9(6):520-8.

Bai Z, Chang J, Chen C, et al. Investigating the effect of transcendental meditation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens 2015;29:653.

Paul-Labrador M, Polk D, Dwyer J, et al. Effects of a randomized controlled trial of Transcendental Meditation on components of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1218-24.

Orme-Johnson DW, Barnes VA, Schneider R. Transcendental Meditation for primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. In: Allan R, Fisher J, editors. Heart & mind: The practice of cardiac psychology. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. p. 365-79.

Castillo-Richmond A, Schneider R, Alexander C, et al. Effects of stress reduction on carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive African Americans. Stroke 2000;31:568-73.

Schneider RH, Alexander CN, Staggers F, et al. Long-term effects of stress reduction on mortality in persons > 55 years of age with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2005;95(9):1060-4.

Schneider R, Grim C, Rainforth M, et al. Stress reduction in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Randomized controlled trial of Transcendental Meditation and health education in Blacks. Circulation 2012;5:750-8.

Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011;124(22):2458-73.

Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, et al. Enhancing cardiac rehabilitation with stress management training: A randomized clinical efficacy trial. Circulation 2016;133(14):1341-50.

Taqueti VR, Shaw LJ, Cook NR, et al. Excess cardiovascular risk in women relative to men referred for coronary angiography is associated with severely impaired coronary flow reserve, not obstructive disease. Circulation 2017;135(6):566-77.

Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation 2015;131(1):19-27.

Blomster JI, Svedlund S, Westergren HU, et al. Coronary flow reserve as a link between exercise capacity, cardiac systolic and diastolic function. Int J Cardiol 2016;217:161-6.

Schindler TH, Zhang XL, Vincenti G, et al. Role of PET in the evaluation and understanding of coronary physiology. J Nucl Cardiol 2007;14(4):589-603.

Klocke FJ, Baird MG, Lorell BH, et al. ACC/AHA/ASNC guidelines for the clinical use of cardiac radionuclide imaging-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASNC Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Cardiac Radionuclide Imaging). Circulation 2003;108:1-15.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Proposed Decision Memo for Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs (CAG-00089R). 2006.

Sheps DS, McMahon RP, Becker L, et al. Mental stress-induced ischemia and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the Psychophysiological Investigations of Myocardial Ischemia study. Circulation 2002;105(15):1780-4.

Schindler TH, Quercioli A, Valenta I, et al. Quantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow-clinical and research applications. Semin Nucl Med 2014;44(4):274-93.

Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, et al. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(18):1639-53.

Curb J, Labarthe D, Cooper S, et al. Training and certification of BP observers. Hypertension 1983;5:610-4.

Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. BDI-II. Beck depression inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996.

American College of Sport Medicine. Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 2005.

Orme-Johnson D, Walton K. All approaches to preventing or reversing effects of stress are not the same. Am J Health Promot 1998;12(5):297-9.

Schneider R, Carr T. Transcendental Meditation in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease and pathophysiological mechanisms: An evidence-based review. Adv Integr Med 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aimed.2014.08.003.

Roth R. Strength in stillness: The power of transcendental meditation. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2018.

Rosenthal N. Transcendence: Healing and transformation through transcendental meditation. NYC: Penguin-Tarcher; 2011.

Tijssen J, Kolm P. Demystifying the new statistical recommendations: The use and reporting of p values. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68(2):231-3.

Hedges L. Unbiased estimation of effect size. Eval Educ 1980;4:25-7.

Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation 2011;124(20):2215-24.

Gupta A, Taqueti VR, van de Hoef TP, et al. Integrated noninvasive physiological assessment of coronary circulatory function and impact on cardiovascular mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation 2017;136(24):2325-36.

Gunnoo T, Hasan N, Khan MS, et al. Quantifying the risk of heart disease following acute ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of over 50,000 participants. BMJ Open 2016;6(1):e009535.

Sdringola S, Nakagawa K, Nakagawa Y, et al. Combined intense lifestyle and pharmacologic lipid treatment further reduce coronary events and myocardial perfusion abnormalities compared with usual-care cholesterol-lowering drugs in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41(2):263-72.

Czernin J, Barnard RJ, Sun KT, et al. Effect of short-term cardiovascular conditioning and low-fat diet on myocardial blood flow and flow reserve. Circulation 1995;92(2):197-204.

Yoshinaga K, Beanlands RS, Dekemp RA, et al. Effect of exercise training on myocardial blood flow in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2006;151(6):1324 e11-8.

Gould LK, Ornish D, Scherwitz L, et al. Changes in myocardial perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after long-term, intense risk factor modification. J Am Med Assoc 1995;274:894-901.

Zamarra JW, Schneider RH, Besseghini I, et al. Usefulness of the Transcendental Meditation program in the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:77-80.

Kallikazaros I, Tsioufis C, Sideris S, et al. Carotid artery disease as a marker for the presence of severe coronary artery disease in patients evaluated for chest pain. Stroke 1999;30(5):1002-7.

Nambi V, Pedroza C, Kao LS. Carotid intima-media thickness and cardiovascular events. Lancet 2012;379(9831):2028-30.

Leucker TM, Valenta I, Schindler TH. Positron emission tomography-determined hyperemic flow, myocardial flow reserve, and flow gradient-quo vadis? Front Cardiovasc Med 2017;4:46.

Ooi SL, Giovino M, Pak SC. Transcendental meditation for lowering blood pressure: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Complement Ther Med 2017;34:26-34.

Diamond GA, Kaul S. On reporting of effect size in randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol 2013;111(4):613-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Magnolia Jimenez for her data collection and administrative contributions, Laura Alcorn for data management, and Linda Heaton and Carol Jarvis for administrative and technical support. Ines Spinal, Claudia Rodriguez, and Josh Pittman taught the Transcendental Meditation program.

Disclosures

All the authors report that there are no relevant, financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant from NIH—National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, # HL 100386.

The authors of this article have provided a PowerPoint file, available for download at SpringerLink, which summarises the contents of the paper and is free for re-use at meetings and presentations. Search for the article DOI on SpringerLink.com

All editorial decisions for this article, including selection of reviewers and the final decision, were made by guest editor Stephan Nekolla, MD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bokhari, S., Schneider, R.H., Salerno, J.W. et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation with and without meditation on myocardial blood flow using quantitative positron emission tomography: A pilot study. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 28, 1596–1607 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-019-01884-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-019-01884-9