Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the associations between physical fitness levels, health related quality of life (HRQoL) and sarcopenic obesity (SO) and to analyze the usefulness of several physical fitness tests as a screening tool for detecting elderly people with an increased risk of suffering SO.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of a population-based sample.

Setting

Non-institutionalized Spanish elderly participating in the EXERNET multi-centre study.

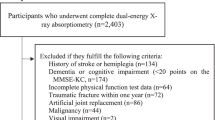

Participants

2747 elderly subjects aged 65 and older.

Measurements

Body weight, height and body mass index were evaluated in each subject. Body composition was measured by bioelectrical impedance. Four SO groups were created based on percentage of body fat and relative muscle mass; 1) normal group, 2) sarcopenic group, 3) obesity group and 4) SO group. Physical fitness was evaluated using 8 tests (balance, lower and upper body strength, lower and upper body flexibility, agility, walking speed and aerobic capacity). Three tertiles were created for each test based on the calculated scores. HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQol visual analogue scale.

Results

Participants with SO showed lower physical fitness levels compared with normal subjects. Better balance, agility, and aerobic capacity were associated to a lower risk of suffering SO in the fittest men (odds ratio < 0.30). In women, better balance, walking speed, and aerobic capacity were associated to a lower risk of suffering SO in the fittest women (odds ratio < 0.21) Superior perceived health was associated with better physical fitness performance.

Conclusions

Higher levels of physical fitness were associated with a reduced risk of suffering SO and better perceived health among elderly. SO elderly people have lower physical functional levels than healthy counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010 Jul;39(4):412–23.

Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Fielding RA, et al. Aging of skeletal muscle: a 12-yr longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol. 2000 Apr;88(4):1321–6.

Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Jan;52(1):80–5.

Baumgartner RN. Body composition in healthy aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000 May;904:437–48.

Han TS, Tajar A, Lean ME. Obesity and weight management in the elderly. Br Med Bull. 2011;97:169–96.

Gomez-Cabello A, Pedrero-Chamizo R, Olivares PR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in non-institutionalized people aged 65 or over from Spain: the elderly EXERNET multi-centre study. Obes Rev. 2011 Aug;12(8):583–92.

Bouchard DR, Dionne IJ, Brochu M. Sarcopenic/obesity and physical capacity in older men and women: data from the Nutrition as a Determinant of Successful Aging (NuAge)-the Quebec longitudinal Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009 Nov;17(11):2082–8.

Baumgartner RN, Wayne SJ, Waters DL, et al. Sarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderly. Obes Res. 2004 Dec;12(12):1995–2004.

Zoico E, Di Francesco V, Guralnik JM, et al. Physical disability and muscular strength in relation to obesity and different body composition indexes in a sample of healthy elderly women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Feb;28(2):234–41.

Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cristini C, et al. Difficulties with physical function associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic-obesity in community-dwelling elderly women: the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l'OSteoporose) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jun;89(6):1895–900.

Guralnik JM, Branch LG, Cummings SR, et al. Physical performance measures in aging research. J Gerontol. 1989 Sep;44(5):M141–6.

Wittink H, Rogers W, Sukiennik A, et al. Physical functioning: self-report and performance measures are related but distinct. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003 Oct 15;28(20):2407–13.

ACSM S. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998 Jun;30(6):975–91.

Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, et al. Physical activity and older adults: a review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. J Sports Sci. 2004 Aug;22(8):703–25.

Kell RT, Bell G, Quinney A. Musculoskeletal fitness, health outcomes and quality of life. Sports Med. 2001;31(12):863–73.

Gomez-Cabello A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Albers U, et al. Harmonization process and reliability assessment of anthropometric measurements in the elderly EXERNET multi-centre study. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41752.

Pedrero-Chamizo R, Gomez-Cabello A, Delgado S, et al. Physical fitness levels among independent non-institutionalized Spanish elderly: the elderly EXERNET multi-center study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012 Sep-Oct;55(2):406–16.

Sanchez-Garcia S, Garcia-Pena C, Duque-Lopez MX, et al. Anthropometric measures and nutritional status in a healthy elderly population. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:2.

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, et al. Estimation of skeletal muscle mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis. J Appl Physiol. 2000 Aug;89(2):465–71.

Rantanen T, Guralnik J, Sakari-Rantala R, et al. Disability, physical activity, and muscle strength in older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(2):130–5.

Davison KK, Ford ES, Cogswell ME, et al. Percentage of body fat and body mass index are associated with mobility limitations in people aged 70 and older from NHANES III. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002 Nov;50(11):1802–9.

Johnson B, Nelson J. Practical measurements for evaluation in physical education. 4th Edit. Burgess ed. Minneapolis, Minnesota 1986.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Senior Fitness Test Manual. Champaign, IL.: Human Kinetics; 2001.

Carvalho C, Sunnerhagen KS, Willen C. Walking speed and distance in different environments of subjects in the later stage post-stroke. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010 Nov;26(8):519–27.

Badia X, Roset M, Montserrat S, et al. [The Spanish version of EuroQol: a description and its applications. European Quality of Life scale]. Med Clin (Barc). 1999;112 Suppl 1:79–85.

EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990 Dec;16(3):199–208.

Olivares PR, Gusi N, Prieto J, et al. Fitness and health-related quality of life dimensions in community-dwelling middle aged and older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:117.

Waters DL, Hale L, Grant AM, et al. Osteoporosis and gait and balance disturbances in older sarcopenic obese New Zealanders. Osteoporos Int. 2009 Feb;21(2):351–7.

Oliveira R, Bottaro M, Júnior J, et al. Identification of sarcopenic obesity in postmenopausal women: a cutoff proposal. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2011;44:1171–6.

Messier V, Karelis AD, Lavoie ME, et al. Metabolic profile and quality of life in class I sarcopenic overweight and obese postmenopausal women: a MONET study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009 Feb;34(1):18–24.

Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, et al. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999 Mar 1;107(2):123–36.

Ryu M, Jo J, Lee Y, et al. Association of physical activity with sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in community-dwelling older adults: the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Age Ageing. 2013 Jun 11.

Crespo CJ, Keteyian SJ, Heath GW, et al. Leisure-time physical activity among US adults. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 1996 Jan 8;156(1):93–8.

Gomez-Cabello A, Pedrero-Chamizo R, Olivares PR, et al. Sitting time increases the overweight and obesity risk independently of walking time in elderly people from Spain. Maturitas. 2012 Dec;73(4):337–43.

Heinonen I, Helajarvi H, Pahkala K, et al. Sedentary behaviours and obesity in adults: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6).

Ochi M, Tabara Y, Kido T, et al. Quadriceps sarcopenia and visceral obesity are risk factors for postural instability in the middle-aged to elderly population. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010 Jul;10(3):233–43.

Marsh AP, Rejeski WJ, Espeland MA, et al. Muscle strength and BMI as predictors of major mobility disability in the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders pilot (LIFE-P). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011 Dec;66(12):1376–83.

Marcell TJ, Hawkins SA, Wiswell RA. Leg Strength Declines with Advancing Age Despite Habitual Endurance Exercise in Active Older Adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Sep 14.

Orr R, Raymond J, Fiatarone Singh M. Efficacy of progressive resistance training on balance performance in older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2008;38(4):317–43.

Handrigan G, Hue O, Simoneau M, et al. Weight loss and muscular strength affect static balance control. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 May;34(5):936–42.

Stenholm S, Alley D, Bandinelli S, et al. The effect of obesity combined with low muscle strength on decline in mobility in older persons: results from the InCHIANTI study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009 Jun;33(6):635–44.

So WY, Choi DH. Differences in Physical Fitness and Cardiovascular Function Depend on BMI in Korean Men. J Sports Sci Med. 2010;9(2):239–44.

Stenholm S, Rantanen T, Heliovaara M, et al. The mediating role of C-reactive protein and handgrip strength between obesity and walking limitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Mar;56(3):462–9.

Bouchard DR, Janssen I. Dynapenic-obesity and physical function in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010 Jan;65(1):71–7.

Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, et al. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003 Nov;95(5):1851–60.

Sayer AA, Syddall HE, Martin HJ, et al. Is grip strength associated with healthrelated quality of life? Findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2006 Jul;35(4):409–15.

Wanderley FA, Silva G, Marques E, et al. Associations between objectively assessed physical activity levels and fitness and self-reported health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res. 2011 Nov;20(9):1371–8.

Brovold T, Skelton DA, Bergland A. Association Between Health-Related Quality of Life, Physical Fitness and Physical Activity in Older People Recently Discharged from Hospital. J Aging Phys Act. 2013 Aug 27;In press.

Takata Y, Ansai T, Soh I, et al. Quality of life and physical fitness in an 85-year-old population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010 May-Jun;50(3):272–6.

Carter ND, Khan KM, Mallinson A, et al. Knee extension strength is a significant determinant of static and dynamic balance as well as quality of life in older community-dwelling women with osteoporosis. Gerontology. 2002 Nov- Dec;48(6):360–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pedrero-Chamizo, R., Gómez-Cabello, A., Mélendez, A. et al. Higher levels of physical fitness are associated with a reduced risk of suffering sarcopenic obesity and better perceived health among the elderly. The EXERNET multi-center study. J Nutr Health Aging 19, 211–217 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0530-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0530-4