Abstract

Purpose

Canadian seniors who undergo hip and knee arthroplasty often experience significant postoperative pain, which could result in persistent opioid use. We aimed to document the impact of preoperative opioid use and other characteristics on postoperative opioid prescriptions in elderly patients following hip and knee replacement before widespread dissemination of opioid reduction strategies.

Methods

We conducted a historical cohort study to evaluate postoperative opioid use in patients over 65 yr undergoing primary total hip and knee replacement over a ten-year period from 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2016, using linked de-identified Ontario administrative data. We determined the use of preoperative opioids and the duration of postoperative opioid prescriptions (short-term [1–90 days], prolonged [91–180 days], chronic [181–365 days], or undocumented).

Results

The study included 49,638 hip and 85,558 knee replacement patients. Eighteen percent of hip and 21% of knee replacement patients received an opioid prescription within 90 days before surgery. Postoperatively, 51% of patients filled opioid prescriptions for 1–90 days, while 24% of hip and 29% of knee replacement patients filled prescriptions between 6 and 12 months, with no impact of preoperative opioid use. Residence in long-term care was a significant predictor of chronic opioid use (hip: odds ratio [OR], 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.93 to 3.59; knee: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.75 to 3.45); other risk factors included female sex and increased comorbidities.

Conclusion

Despite a main goal of joint arthroplasty being relief of pain, seniors commonly remained on postoperative opioids, even if not receiving opioids before surgery. Opioid reduction strategies need to be implemented at the surgical, primary physician, long-term care, and patient levels. These findings form a basis for future investigations following implementation of opioid reduction approaches.

Résumé

Objectif

Les aînés canadiens subissant une arthroplastie de la hanche ou du genou éprouvent souvent une douleur postopératoire importante, ce qui pourrait entraîner la consommation persistante d’opioïdes. Nous avons cherché à documenter l’impact d’une utilisation préopératoire d’opioïdes et d’autres caractéristiques sur les prescriptions postopératoires d’opioïdes chez les patients âgés suivant un remplacement de hanche ou de genou avant l’utilisation répandue de stratégies de réduction d’opioïdes.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé une étude de cohorte historique pour évaluer la consommation postopératoire d’opioïdes chez les patients de plus de 65 ans subissant une arthroplastie totale primaire de la hanche ou du genou sur une période de dix ans du 1er avril 2006 au 31 mars 2016, à l’aide de données administratives dépersonnalisées et codées de l’Ontario. Nous avons déterminé la durée des ordonnances préopératoires et postopératoires d’opioïdes (à court terme [1-90 jours], prolongées [91-180 jours], chroniques [181-365 jours] ou non documentées).

Résultats

L’étude a porté sur 49 638 patients ayant subi une arthroplastie de la hanche et 85 558 patients une arthroplastie du genou. Dix-huit pour cent des patients ayant subi une arthroplastie de la hanche et 21 % des patients ayant subi une arthroplastie du genou ont reçu une ordonnance d’opioïdes dans les 90 jours précédant leur chirurgie. En période postopératoire, 51 % des patients ont utilisé leurs ordonnances d’opioïdes pendant 1 à 90 jours, tandis que 24 % des patients d’arthroplastie de la hanche et 29 % des patients d’arthroplastie du genou ont utilisé leurs ordonnances entre six et 12 mois. Le fait d’habiter dans un établissement de soins de longue durée était un prédicteur important de consommation chronique d’opioïdes (hanche : rapport de cotes [RC], 2,64; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %, 1,93 à 3,59; genou : RC, 2,46; IC 95 %, 1,75 à 3,45); le sexe féminin et l’augmentation des comorbidités constituaient d’autres facteurs de risque.

Conclusion

Bien que l’un des principaux objectifs de l’arthroplastie articulaire soit le soulagement de la douleur, les personnes âgées continuent généralement à consommer des opioïdes en période postopératoire, même si elles ne prenaient pas d’opioïdes avant leur chirurgie. Il est nécessaire de mettre en œuvre des stratégies de réduction des opioïdes qui s’adressent aux chirurgiens, aux médecins traitants, aux soins de longue durée et aux patients. Ces constatations constituent la base d’études futures réalisées à la suite de la mise en œuvre d’approches de réduction des opioïdes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Each year, over 200 million surgical patients worldwide are treated with opioids for acute postoperative pain.1 Short-term postoperative administration of opioids may be helpful in managing pain and improving the rehabilitation process; however, adverse events and the development of dependency may limit their safe use and effectiveness.2 The rate of prescription opioid use among Canadian seniors (aged ≥ 65 yr) was 13.2% in 2015, which was among the highest of any age group.3 Many elderly patients present for joint replacement surgery to relieve chronic arthritic pain4; in 2018 –2019, roughly two of every three patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery were over the age of 65 in Canada.5 Although the goal of joint replacement is to relieve pain and improve quality of life, arthroplasty surgery is associated with an incidence of chronic post-surgical pain of 10–41%.6 Many patients scheduled for surgery receive opioids preoperatively,7 yet those who have not previously used opioids are also at risk of becoming chronic opioid users after surgery.8,9,10,11 In fact, long-term opioid dependence is a common post-surgical complication.12 Despite a large body of literature on postoperative opioid use, few large studies have addressed the impact of preoperative opioids on chronic postoperative use, particularly in elderly patients in public healthcare systems.10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

In recent years, Canadian and international policy guidelines have been developed to guide opioid use in the management of chronic non-malignant pain, as well as postoperative pain.22,23,24,25,26,27 The aim of the current study was to establish baseline data over a ten-year period prior to the publication of recent opioid guidelines, with a view to determine the impact of this information on postoperative prescribing habits following guideline dissemination. Specifically, using health administrative data in a cohort of over 135,000 Ontario seniors, we aimed to 1) document the duration of opioid use after major joint surgery, and 2) identify predictors, including preoperative opioid use, of chronic postoperative opioid prescribing in this population.

Methods

Study design, setting, sample, and data sources

We conducted a historical cohort study utilizing linked de-identified population-level administrative databases for the Canadian province of Ontario (Table 1). The study cohort comprised patients aged 66 yr and older who underwent primary total hip or knee replacement between 1 April 2006 and 31 March 2016, with follow up to 31 March 2017.28 For each patient, only the first arthroplasty procedure occurring during the study period was considered. Patients were identified using Ontario Health Insurance Plan billing codes and corresponding hospital admission data (in the Canadian Institute for Health Information-Discharge Abstract Database [CIHI-DAD] and the Canadian Institute for Health Information-Same Day Surgery Database [CIHI-SDS]).29 The observation window ended on the discharge date plus 365 days, or on the date of death if earlier.

In Ontario, drug prescriptions for patients 65 yr and older are reimbursed and stored in the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) database. Preoperative opioid use was considered if patients filled an opioid prescription during a 90-day period prior to surgery. Preoperative comorbid conditions were identified from health records during the two years prior to surgery.

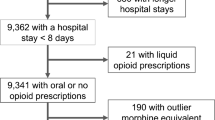

Exclusion criteria consisted of advanced cancer or palliative care during one year before and after the surgical admission; hip or femur fracture within one month before admission; osteomyelitis or septic arthritis within one year before admission; pre-existing pain disorders from unrelated causes; missing a valid healthcare number; not admitted to hospital; age > 105 yr; missing age or sex codes; non-Ontario resident status; and, if deceased during the follow up period, invalid or missing dates of death (Table 2).

The linked population level administrative databases accessed (Table 1) are housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES, www.ices.on.ca), and have been previously validated for many comorbidities, outcomes, and exposures.28,29,30,31,32 The ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. The databases reflect Ontario’s provision of public universal access to physician and hospital healthcare services to its 13.7 million inhabitants (2014). These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Subgroup results, which included less than six patients, were omitted because of privacy regulations. Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board of Queen’s University.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics include age, sex, socioeconomic status (Statistics Canada neighbourhood median income quintile), rurality, region of the province (by Local Health Integration Network),33 number of subsequent joint replacements (hip and knee), Charlson comorbidity index with a two-year look-back window, and residence in a long-term care (LTC) facility in the previous two years. The following comorbidities were documented: diabetes; hypertension; heart failure; malignancy; chronic renal insufficiency or dialysis; and pulmonary, peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular, and coronary artery diseases (using International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10] codes).34 We compared rates of opioid utilization across regions of the province and by hospital teaching status (teaching vs non-teaching institution).

Outcomes

Opioid prescriptions were identified if filled during the 90 days prior to surgical admission, and included hydromorphone, meperidine, morphine, oxycodone, codeine, tramadol, fentanyl patch, and “other opioids”. Two patient cohorts were created: no preoperative opioids (no prescription for opioids within the 90 days prior to index admission) and preoperative opioids (at least one opioid prescription within 90 days prior to index admission).8,10

Postoperative opioid prescriptions were categorized by the number of days following the surgical discharge date that the last prescription was filled:10,13,15

-

1.

Undocumented (0 days recorded);

-

2.

Short-term opioids (1–90 days);

-

3.

Prolonged opioids (91–180 days);

-

4.

Chronic opioids (181–360 days).

Statistical analysis

Opioid prescriptions filled after surgery were presented using descriptive statistics. We calculated means and standard deviations for continuous variables and expressed categorical variables as percentages. Bivariate tests were used to compare patients with and without chronic opioid prescriptions. We evaluated the relationship between type of surgery and duration of opioid use using multivariable logistic regression and calculation of odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs); for each of the procedures (hip and knee replacements), a separate logistic regression was conducted. Possible confounders were controlled through multivariate logistic regression analysis, including age, sex, socioeconomic status, residence, comorbidities, preoperative opioid utilization, and survival. Statistical significance was ascertained for two-tailed P values < 0.05. SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was utilized to conduct analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

Between 1 April 1 2006 and 31 March 31 2016, a total of 299,371 patients underwent total hip or knee arthroplasty in Ontario. Of these, cohorts of 49,638 (36.7%) hip replacement and 85,558 (63.3%) knee replacement patients who were 66 yr of age or older and met inclusion criteria were created (Table 2). Baseline characteristics and comorbidities are detailed in Tables 3A–D. The mean age of hip surgery patients was 75.0 yr and 35.0% were female. The mean age of knee surgery patients was 74.1 yr and 36.3% were female. Spinal anesthesia was performed in 76.7% vs general anesthesia in 19.3% of hip surgeries, and 78.4% vs 17.6% of knee surgeries.

As shown in Figure A and B, postoperatively, 25,353 (51.1%) hip surgery and 43,612 (51.0%) knee surgery patients were in the short-term opioid group, 3,085 (6.2%) hip and 7,359 (8.6%) knee surgery patients were in the prolonged opioid group, and 12,044 (24.3%) hip and 25,137 (29.4%) knee surgery patients were in the chronic opioid group. There were no outpatient opioid prescriptions documented in 9,156 (18.4%) hip and 9,450 (11.0%) knee surgery patients after surgical discharge.

Overall, 8,853 (17.8%) hip and 17,549 (20.5%) knee surgery patients had received opioid prescriptions in the 90 days prior to surgery. Preoperative opioid use was not predictive of chronic opioid prescriptions postoperatively: 24.6% of those not receiving opioids preoperatively vs 22.9% of preoperative opioid users received opioid prescriptions chronically after hip surgery; 29.3% of those not receiving opioids preoperatively vs 29.7% of preoperative opioid users received opioid prescriptions chronically after knee surgery.

Predictors of chronic opioid prescriptions

The results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis conducted to assess the effects of patient characteristics on chronic opioid use compared with short-term use are presented in Table 4, including ORs and their corresponding 95% CIs. Predictors included residence in an LTC facility (hip: OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.93 to 3.59; knee: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.75 to 3.45); female sex (hip: OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.27 to 1.40; knee: OR, 1.26, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.30) and living in urban areas (hip: OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.20; knee: OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.20). Patients in higher income quintiles were less likely to be in the chronic opioid use group than those in the lower income quintiles; with every incremental increase in income quintile, there was approximately a 10% decrease in the odds of chronic use. Likewise, an increasing Charlson comorbidity score was associated with a higher incidence of chronic opioid use as shown in Table 4 (OR for Charlson score > 3 vs 0, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.72 to 2.30 for hip surgery; OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.31 to 1.64 for knee surgery).

Discussion

Brief summary of main results

In this historical cohort study evaluating postoperative opioid use in over 135,000 older patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement over a ten-year period in Ontario, 17.8% of hip surgery and 20.5% of knee surgery patients received at least one opioid prescription within 90 days before surgery. We found that 24.3% of hip and 29.4% of knee patients were still filling opioid prescriptions 6–12 months postoperatively, with no predictive effect of preoperative opioid use. Predictors of chronic opioid use included residence in an LTC, higher age, female sex, living in urban areas, lower income quintile, and higher comorbidity index.

Preoperative opioid use

The proportion of patients who had been prescribed opioids prior to hip and knee surgery has been found to range between 6.2% and 87.1%7,13,14,16,20 compared with an overall rate of 19.5% in the current study. While this wide variation may be reflective of differences in local practice, definitions of preoperative opioid use are also highly variable. Jin et al. found that 60% of older arthroplasty patients had been prescribed opioids within one year prior to surgery, although only 12% used opioids continuously over the year.7 In contrast, low rates of preoperative opioid use found by Inacio et al. may be due to stringent definitions of chronic opioid use as 90 consecutive days or 120 non-consecutive days in the year before surgery.20

We found that an equal number of patients who had received and who had not received opioid prescriptions in the 90 days before surgery were still receiving opioids for 6–12 months postoperatively. The proportion of patients with no preoperative opioids who became chronic users postoperatively is variable among different studies, reflecting different practice patterns, definitions, and study designs.13,16,20 Regardless of definitions and populations studied, prolonged postoperative opioid use remains a concerning problem. Especially salient in the current study is the high rate of chronic opioid use in patients who were not on opioids before surgery since pain is one of the main indications for arthroplasty surgery in the first place. Explanations for high rates of chronic opioid use are unclear, but may include persistent postoperative pain, pain from other sources, and iatrogenic opioid dependence. In recent years, new policies and guidelines have emerged within Canada and internationally to regulate physician- and pharmacist-prescribed opioids.23 Both contemporary behavioural strategies and opioid reduction policies have been shown to be effective in reducing opioid use following surgery.24,25,26,35 As such, the current study will form a basis for future research to evaluate the impact of these new policies on opioid use.

Predictors of chronic opioid use

For participants in the current study, risk factors for chronic opioid use included higher comorbidity score, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure, similar to other studies.15,16 A unique finding in the current study was that residence in an LTC facility was a significant predictor of chronic opioid use. Nevertheless, the absolute number of patients residing in LTC is small, and thus the net effect of reducing opioid use in this group would be limited. Despite this, in Ontario, rates of opioid use in LTC facilities have increased from 15.8% in 2009–2010 to 19.6% in 2016–2017.36 Thus, opioid reduction strategies that specifically target the postoperative care of residents of LTC facilities are warranted.

Strengths and limitations

This study comprised a large sample size, allowing the inclusion of a variety of potential risk factors for chronic postoperative opioid use. The ICES administrative databases minimized the risk of missing data by ensuring the study included comprehensive data of patients’ demographics, hospitalizations, comorbidities, medications, and procedures. There was likely no significant prescription recall bias as may have been the case in other studies relying on surgeon or patient self-reported accounts. The relationship between opioid utilization and pain was not confirmed, although studies have shown that opioid utilization is a suitable proxy for the assessment of pain.37,38 Data sources used in this study did not include reasons for opioid prescriptions; patients may have been prescribed opioids for other indications, including new injuries or surgical procedures. Although opioid data represent prescriptions that were filled, actual intake and dosing were not available. Certain confounders or risk factors are difficult to account for, such as other pain conditions, physiologic opioid dependence,10 functional status, psychological well-being, and prescribers’ preferences and specialty. Nevertheless, data show that osteoarthritis, rather than rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory conditions, is the underlying diagnosis for 95.3% of primary hip and 98.8% of primary knee arthroplasties.5,39 This study focused on a cohort of senior patients; as such, the findings of the study may not be generalizable to younger populations. Severity of arthritis, wait times, perioperative management and longitudinal trends over the study period were not analyzed in this study, but would be important in future research directions. Overall, 11.2% of patients had no documented opioid prescriptions: as only outpatient prescriptions were identified, many of these patients likely received opioids as inpatients in acute or rehabilitation hospitals. Furthermore, opioid prescriptions remunerated from other sources, including private insurance, out of pocket, and illicit means, were not accounted for in the ODB data.

Conclusion

In a cohort of over 135,000 seniors, 12,044 (24.3%) of hip arthroplasty and 25,137 (29.4%) of knee arthroplasty patients were still being prescribed opioids at 6–12 months following surgery. Patients who were not receiving opioids preoperatively were just as likely to become chronic opioid users as those who had been receiving opioids before surgery. Residence in an LTC facility was a significant predictor of chronic postoperative opioid use. The results of this study indicate a need to evaluate and optimize opioid reduction strategies and education at the surgical care, primary physician, LTC, and patient levels. This study will form a basis for future quality improvement research following implementation of opioid reduction programs and guidelines.

References

[1] Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 2008; 372: 139-44.

[2] Simoni-Wastila L, Yang HK. Psychoactive drug abuse in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006; 4: 380-94.

Canadian Centre on Drug Abuse and Addiction. Canadian drug summary: prescription opioids. Ottawa, ON. Available from URL: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Canadian-Drug-Summary-Prescription-Opioids-2017-en.pdf (accessed July 2021).

[4] Petersen KK, Arendt-Nielsen L. Chronic postoperative pain after joint replacement. Pain Clinical Updates 2016; 24: 1-6.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hip and knee replacements in Canada: CJRR annual statistics summary, 2018-2019. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; August 2020. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/cjrr-annual-statistics-hip-knee-2018-2019-report-en.pdf (accessed July 2021).

[6] Wylde V, Sayers A, Lenguerrand E, et al. Preoperative widespread pain sensitization and chronic pain after hip and knee replacement: a cohort analysis. Pain 2015; 156: 47-54.

[7] Jin Y, Solomon DH, Franklin PD, et al. Patterns of prescription opioid use before total hip and knee replacement among US Medicare enrollees. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019; 27: 1445-53.

[8] Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 1286-93.

[9] Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 425-30.

[10] Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ 2014; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1251.

[11] Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, et al. Chronic use of opioid medications before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2013; 310: 1369-76.

[12] Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 1066-71.

[13] Namba RS, Singh A, Paxton EW, Inacio MC. Patient factors associated with prolonged postoperative opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018; 33: 2449-54.

[14] Sheth DS, Ho N, Pio JR, Zill P, Tovar S, Namba RS. Prolonged opioid use after primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty: prospective evaluation of risk factors and psychological profile for depression, pain catastrophizing, and aberrant drug-related behavior. J Arthroplasty 2020; 35: 3535-44.

[15] Gold LS, Strassels SA, Hansen RN. Health care costs and utilization in patients receiving prescriptions for long-acting opioids for acute postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain 2016; 32: 747-54.

[16] Kim SC, Choudhry N, Franklin JM, et al. Patterns and predictors of persistent opioid use following hip or knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017; 25: 1399-406.

[17] Cook DJ, Kaskovich SW, Pirkle SC, Mica MA, Shi LL, Lee MJ. Benchmarks of duration and magnitude of opioid consumption after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a database analysis of 69,368 patients. J Arthroplasty 2019; 34: 638-44.e1.

[18] Westermann RW, Mather RC 3rd, Bedard NA, et al. Prescription opioid use before and after hip arthroscopy: a caution to prescribers. Arthroscopy 2019; 35: 453-60.

[19] Pryymachenko Y, Wilson RA, Abbott JH, Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Risk factors for chronic opioid use following hip and knee arthroplasty: evidence from New Zealand population data. J Arthroplasty 2020; 35: 3099-107.e14.

[20] Inacio MC, Hansen C, Pratt NL, Graves SE, Roughead EE. Risk factors for persistent and new chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010664.

[21] Naylor JM, Pavlovic N, Farrugia M, et al. Associations between pre-surgical daily opioid use and short-term outcomes following knee or hip arthroplasty: a prospective, exploratory cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03413-z.

[22] Hah JM, Bateman BT, Ratliff J, Curtin C, Sun E. Chronic opioid use after surgery: implications for perioperative management in the face of the opioid epidemic. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 1733-40.

[23] Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017 May 8; 189: E659-66.

[24] Zhang DD, Sussman J, Dossa F, et al. A systematic review of behavioral interventions to decrease opioid prescribing after surgery. Ann Surg 2020; 271: 266-78.

[25] Whale CS, Henningsen JD, Huff S, Schneider AD, Hijji FY, Froehle AW. Effects of the Ohio opioid prescribing guidelines on total joint arthroplasty postsurgical prescribing and refilling behavior of surgeons and patients. J Arthroplasty 2020; 35: 2397-404.

[26] Wyles CC, Hevesi M, Ubl DS, et al. Implementation of procedure-specific opioid guidelines: a readily employable strategy to improve consistency and decrease excessive prescribing following orthopaedic surgery. JB JS Open Access 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.19.00050.

[27] McKeen DM, Banfield JC, McIsaac DI, et al. Top ten priorities for anesthesia and perioperative research: a report from the Canadian Anesthesia Research Priority Setting Partnership. Can J Anesth 2020; 67: 641-54.

[28] Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009; 120: e169-276.

Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, Chong A, Austin P, Tu J, Lupacis A. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: A Validation Study. Ottawa, ON; Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; June 2006. Available from URL: https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2006/Canadian-Institute-for-Health-Information (accessed July 2021).

[30] Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J 2002; 144: 290-6.

[31] Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 512-6.

[32] Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 10: 67-71.

Local Health Integration Network. Local Health Integration Network (LHINs) plan, integrate and fund local health care, improving access and patient experience 2014. Available from URL: http://www.lhins.on.ca/ (accessed July 2021).

[34] Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43: 1130-9.

[35] Alvis BD, Amsler RG, Leisy PJ, et al. Effects of an anesthesia perioperative surgical home for total knee and hip arthroplasty at a Veterans Affairs Hospital: a quality improvement before-and-after cohort study. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 367-75.

[36] Iaboni A, Campitelli MA, Bronskill SE, et al. Time trends in opioid prescribing among Ontario long-term care residents: a repeated cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open 2019; 7: E582-9.

[37] Zhang W, Moskowitz R, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008; 16: 137-62.

[38] Breivik H, Borchgrevink P, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 17-24.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada, 2017–2018: Canadian Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report. Ottawa, ON. Available from URL: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/cjrr-annual-report-2019-en-web.pdf (accessed July 2021).

Author contributions

Ana Johnson, Joel Parlow, and Brian Milne contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Ian Gilron, Narges Jamali, Matthew Pasquali, and Steve Mann contributed to interpretation of data and drafting the article. Kieran Moore contributed to the design of the study. Erin Graves contributed to data acquisition and analysis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc for use of their Drug Information File.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

This project was funded by an Applied Health Research Question (AHRQ) grant from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, ON, Canada.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K.W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, A., Milne, B., Pasquali, M. et al. Long-term opioid use in seniors following hip and knee arthroplasty in Ontario: a historical cohort study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 934–944 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02091-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02091-2