Abstract

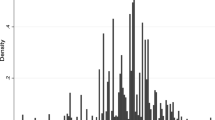

Although substantial research has explored the causes of India’s excessively masculine population sex ratio, few studies have examined the consequences of this surplus of males. We merge individual-level data from the 2004–2005 India Human Development Survey with data from the 2001 India population census to examine the association between the district-level male-to-female sex ratio at ages 15 to 39 and self-reports of victimization by theft, breaking and entering, and assault. Multilevel logistic regression analyses reveal positive and statistically significant albeit substantively modest effects of the district-level sex ratio on all three victimization risks. We also find that higher male-to-female sex ratios are associated with the perception that young unmarried women in the local community are frequently harassed. Household-level indicators of family structure, socioeconomic status, and caste, as well as areal indicators of women’s empowerment and collective efficacy, also emerge as significant predictors of self-reported criminal victimization and the perceived harassment of young women. The implications of these findings for India’s growing sex ratio imbalance are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Indian demography, the sex ratio is traditionally expressed as the number of females per males. Unless otherwise noted, we adopt the convention for measuring the sex ratio that is used the most elsewhere in the world: the number of males per females.

This question was also asked of the household heads, but the women respondents are likely better positioned to report accurately about the frequency of harassment of young girls.

We also estimated models using the age range 15 to 29, with similar results. However, using the sex ratio for the total population—with no age constraints—generated much weaker and often nonsignificant associations. We tested for nonlinear effects of the sex ratio by including polynomial terms but found no evidence of statistically significant departures from linearity.

Although region could be considered a third level of aggregation, for simplicity, we treat it as a Level 2 variable.

The sample size varies across the dependent variables because of differential (albeit small) amounts of missing data and because the harassment of young girls item was taken from the sample of ever-married women. We present descriptive statistics on the independent variables for the largest sample (N = 41,404), but statistics for the other samples are quite comparable (results not shown).

References

Agnihotri, S. B. (2000). Sex ratio patterns in the India population: A fresh exploration. New Delhi, India: Sage.

Ahern, J., Cerda, M., Lippman, S. A., Tardiff, K. J., Viahov, D., & Galea, S. (2013). Navigating non-positivity in neighbourhood studies: An analysis of collective efficacy and violence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67, 159–165.

Anagol-McGinn, P. (1994). Sexual harassment in India: A case study of eve-teasing in historical perspective. In C. Brant & Y. L. Too (Eds.), Rethinking sexual harassment (pp. 220–234). London, UK: Pluto Press.

Antonaccio, O., & Tittle, C. R. (2007). A cross-national test of Bonger’s theory of criminality and economic conditions. Criminology, 45, 925–958.

Arnold, F., Kishor, S., & Roy, T. K. (2002). Sex-selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review, 28, 759–785.

Bandyopadhyay, M. (2003). Missing girls and son preference in rural India: Looking beyond popular myth. Health Care for Women International, 24, 910–926.

Barber, N. (2000). The sex ratio as a predictor of cross-national variation in violent crime. Cross Cultural Research, 34, 264–282.

Barber, N. (2006). Why is violent crime so common in the Americas? Aggressive Behavior, 32, 442–450.

Barber, N. (2009). Countries with fewer males have more violent crime: Marriage markets and mating aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 35, 49–56.

Baxi, P. (2001). Sexual harassment. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from http://www.india-seminar.com/2001/505/505pratikshabaxi.htm

Bhat, P. N. M., & Zavier, A. J. F. (2003). Fertility decline and gender bias in northern India. Demography, 40, 637–657.

Bhat, R. L., & Sharma, N. (2006). Missing girls: Evidence from some northern Indian states. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 13, 351–374.

Borooah, V. K. (2004). Gender bias among children in India in their diet and immunisation against disease. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1719–1731.

Census of India. (2008). Report on post enumeration survey (Census document). Retrieved from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/POST_ENUMERATION/Post_Enumeration.html

Census of India. (2011). Provisional population totals, paper 1 (Census document). Retrieved from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/prov_results_paper1_india.html

Chakraborty, T., & Kim, S. (2010). Kinship institutions and sex ratios in India. Demography, 47, 989–1012.

Clark, S. (2000). Son preference and sex composition of children: Evidence from India. Demography, 37, 95–108.

Croll, E. (2000). Endangered daughters: Discrimination and development in Asia. New York, NY: Routledge.

Das Gupta, M. (1987). Selective discrimination against female children in Rural Punjab, India. Population and Development Review, 13, 77–100.

Das Gupta, M., Zhenghua, J., Li, B., Xie, Z., Chung, W., & Bae, H.-O. (2003). Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India, and the Republic of Korea. Journal of Development Studies, 40, 153–187.

Debnath, A., & Roy, N. (2013). Linkage between internal migration and crime: Evidence from India. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 41, 203–212.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47, 667–687.

Desai, S., Dubey, A., Joshi, B. L., Sen, M., Shariff, A., & Vanneman, R. (2009). India human development survey: Design and data quality (IHDS Technical Paper No. 1). College Park: University of Maryland. Retrieved from http://ihds.umd.edu/tech_reports.html

Dreze, J., & Khera, R. (2000). Crime, gender, and society in India: Insights from homicide data. Population and Development Review, 26, 335–352.

Dyson, T. (2001). The preliminary demography of the 2001 Census of India. Population and Development Review, 27, 341–356.

Dyson, T. (2012). Causes and consequences of skewed sex ratios. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 443–461.

Edlund, L., Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2013). Sex ratios and crime: Evidence from China. Review of Economics and Statistics. Advance online publication. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00356

Garg, S., & Nath, A. (2008). Female feticide in India: Issues and concerns. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 54, 276–279.

George, S. M. (2002). Sex selection/determination in India: Contemporary developments. Reproductive Health Matters, 10, 184–197.

Goodkind, D. M. (2004). China’s missing children: The 2000 census underreporting surprise. Population Studies, 58, 281–295.

Griffiths, P., Matthews, Z., & Hinde, A. (2000). Understanding the sex ratio in India: A simulation approach. Demography, 37, 477–488.

Guillot, M. (2002). The dynamics of the population sex ratio in India, 1971–96. Population Studies, 56, 51–63.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2007, October). Characteristics of sex-ratio imbalance in India, and future scenarios. Paper presented at the 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights, Hyderabad, India.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2008). Economic, social and spatial dimensions of India’s excess child masculinity. Population-E, 63, 91–118.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). The sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35, 519–549.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012). Skewed sex ratio at birth and future marriage squeeze in China and India, 2005–2100. Demography, 49, 77–100.

Guo, G., & Zhao, H. (2000). Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 441–462.

Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. F. (1983). Too many women? The sex ratio question. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Haub, C. (2011, February 9). Update on India’s sex ratio at birth [Population Reference Bureau web log comment]. Retrieved from http://prbblog.org/index.php/2011/02/09/india-sex-ratio-at-birth/

Hesketh, T., & Xing, Z. W. (2006). Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 13271–13275.

Hudson, V., & Den Boer, A. M. (2002). A surplus of men, a deficit of peace: Security and sex ratios in Asia’s largest states. International Security, 26, 5–38.

Hudson, V., & Den Boer, A. M. (2004). Bare branches: The security implications of Asia’s surplus male population. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Hvistendahl, M. (2011). Unnatural selection: Choosing boys over girls, and the consequences of a world full of men. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

Indiastat. (2011). Sex ratio: Figures at India-country/state/region level. Retrieved from http://www.Indiastat.com/demographics/7/sexratio/251/stats.aspx

Jamshedji-Neogi, A., & Sharma, M. L. (2003). Coping with sexuality during adolescence. Journal of Family Welfare, 49, 30–37.

Jha, P., Kumar, R., Vasa, P., Dhingra, N., Thiruchelvam, D., & Moineddin, R. (2006). Low male-to-female sex ratio of children born in India national survey of 1.1 million households. Lancet, 367, 211–218.

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30, 435–464.

Kaur, R. (2004). Across-region marriages: Poverty, female migration and the sex ratio. Economic and Political Weekly, 39, 2595–2603.

King, R. D., Massoglia, M., & MacMillan, R. (2007). The context of marriage and crime: Gender, the propensity to marry, and offending in early adulthood. Criminology, 45, 33–65.

Klasen, S., & Wink, C. (2002). A turning point in gender bias in mortality? An update on the number of missing women. Population and Development Review, 28, 285–312.

Klasen, S., & Wink, C. (2003). “Missing women”: Revisiting the debate. Feminist Economics, 9, 263–299.

Lloyd, K. M., & South, S. J. (1996). Contextual influences on young men’s transition to first marriage. Social Forces, 74, 1097–1119.

Malhotra, A., & Mather, M. (1997). Do schooling and work empower women in developing countries? Gender and domestic decisions in Sri Lanka. Sociological Forum, 12, 599–630.

Malhotra, A., & Schuler, S. R. (2005). Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. In D. Narayan (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 71–88). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Malhotra, A., Vanneman, R., & Kishor, S. (1995). Fertility, dimensions of patriarchy, and development in India. Population and Development Review, 21, 281–305.

Mason, K. O. (1986). The status of women: Conceptual and methodological issues in demographic studies. Sociological Forum, 1, 284–300.

Mason, K. O. (2005). Measuring women’s empowerment: Learning from cross-national research. In D. Narayan (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 89–102). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Mason, K. O., & Smith, H. L. (2000). Husbands’ versus wives’ fertility goals and use of contraception: The influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography, 37, 299–311.

Mayer, P. (1999). India’s falling sex ratios. Population and Development Review, 25, 323–343.

Mayer, P., Brennan, L., Shlomowicz, R., & McDonald, J. (2008, July). Is North India violent because it has a surplus of men? Paper presented at the 17th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia, Melbourne.

Messner, S. F., & Blau, J. R. (1987). Routine leisure activities and rates of crime: A macro-level analysis. Social Forces, 65, 1035–1052.

Messner, S. F., Pearson-Nelson, B., Raffalovich, L. E., & Miner, Z. (2011). Cross-national homicide trends in the latter decades of the twentieth century: Losses and gains in institutional control? In W. Heitmeyer, H. Haupt, S. Malthaner, & A. Kirschner (Eds.), Control of violence: Historical and international perspectives on violence in modern societies (pp. 65–89). New York, NY: Springer.

Messner, S. F., Raffalovich, L. E., & Shrock, P. (2002). Reassessing the cross-national relationship between income inequality and homicide rates: Implications of data quality control in the measurement of the income distribution. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 377–395.

Messner, S. F., Raffalovich, L. E., & Sutton, G. M. (2010). Poverty, infant mortality, and homicide rates in cross-national perspective: Assessments of criterion and construct validity. Criminology, 48, 509–537.

Messner, S. F., & Sampson, R. J. (1991). The sex ratio, family disruption, and rates of violent crime: The paradox of demographic structure. Social Forces, 69, 33–53.

Mishra, V., Roy, T. K., & Retherford, R. D. (2004). Sex differentials in childhood feeding, health care, and nutritional status in India. Population and Development Review, 30, 269–295.

Mitra, A. (1993). Sex ratio and violence: Spurious results. Economic and Political Weekly, 28, 67.

Mohan, V., & Priyadarshini, S. (1995). A survey on eve teasing as experienced by girls. Indian Journal of Criminology and Criminalistics, 16, 1–7.

Morgan, S. P., Stash, S., Smith, H. L., & Mason, K. O. (2002). Muslim and non-Muslim difference in female autonomy and fertility: Evidence from four Asian countries. Population and Development Review, 28, 515–537.

Mukherjee, C., Rustagi, P., & Krishnaji, N. (2001). Crimes against women in India: Analysis of official statistics. Economic and Political Weekly, 36, 4070–4080.

Nivette, A. E. (2011). Cross-national predictors of crime: A meta-analysis. Homicide Studies, 15, 103–131.

O’Brien, R. M. (1991). Sex ratios and rape rates: A power-control theory. Criminology, 29, 99–114.

Oldenburg, P. (1992). Sex ratio, son preference and violence in India: A research note. Economic and Political Weekly, 27, 2557–2662.

Oster, E. (2009). Proximate sources of population sex imbalance in India. Demography, 46, 325–340.

Pande, R. P. (2003). Selective gender differences in childhood nutrition and immunization in rural India: The role of siblings. Demography, 40, 395–418.

Pande, R. P., & Astone, N. M. (2007). Explaining son preference in rural India: The independent role of structural versus individual factors. Population Research and Policy Review, 26, 1–29.

Patel, A. B., Badhoniya, N., Mamtani, M., & Kulkarni, H. (2013). Skewed sex ratios in India: “Physician, heal thyself.” Demography, 50, 1129–1134.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: A meta-analysis. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: A review of research (Vol. 32, pp. 373–450). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Roy, T. K., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2012). Daughter discrimination and future sex ratio at birth in India. Asian Population Studies, 8, 281–299.

Sampson, R. J. (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for further inquiry. In F. T. Cullen, J. P. Wright, & K. R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (pp. 149–167). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Sampson, R. J., Laub, J. H., & Wimer, C. (2006). Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within-individual causal effects. Criminology, 44, 465–508.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924.

Schuler, S. R., & Hashemi, S. M. (1994). Credit programs, women’s empowerment, and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning, 25, 65–76.

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., & Riley, A. P. (1997). The influence of women’s changing roles and status in Bangladesh’s fertility transition: Evidence from a study of credit programs and contraceptive use. World Development, 25, 563–575.

Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., & Rottach, E. (2010). Women’s empowerment revisited: A case study from Bangladesh. Development in Practice, 20, 840–854.

Sen, A. (1992). Missing women. British Medical Journal, 304, 587–588.

South, S. J., & Messner, S. F. (1987). The sex ratio and women’s involvement in crime: A cross-national analysis. The Sociological Quarterly, 28, 171–188.

South, S. J., & Messner, S. F. (2000). Crime and demography: Multiple linkages, reciprocal relations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 83–106.

StataCorp. (2005). Stata statistical software: Release 9.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation.

Steffensmeier, D., & Allan, E. (1996). Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 459–487.

Trent, K., & South, S. J. (2012). Mate availability and women’s sexual experiences in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 201–214.

Tuljapurkar, S., Li, N., & Feldman, M. W. (1995). High sex ratios in China’s future. Science, 267, 874–876.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2011). Errata: Criminal victimization, 2005. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to the authors from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD067214). The Center for Social and Demographic Analysis of the University at Albany provided technical and administrative support for this research through a grant from NICHD (R24 HD044943). We thank Steven Messner and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

South, S.J., Trent, K. & Bose, S. Skewed Sex Ratios and Criminal Victimization in India. Demography 51, 1019–1040 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0289-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0289-6