Abstract

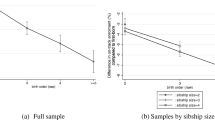

The existing empirical evidence on the effects of birth order on wages does not distinguish between temporary and permanent effects. Using data from 11 European countries for males born between 1935 and 1956, we show that firstborns enjoy on average a 13.7 % premium in their entry wage compared with later-borns. This advantage, however, is short-lived and disappears 10 years after labor market entry. Although firstborns start with a better job, partially because of their higher education, later-borns quickly catch up by switching earlier and more frequently to better-paying jobs. We argue that a key factor driving our findings is that later-borns have lower risk aversion than firstborns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Because information on the first wage is missing for about 25 % of the individuals in our final sample, we use predictive mean matching to impute missing data. Single-imputation predictive mean matching replaces a missing value with the observed value for which the predicted value is the closest to that of the missing value. When we use multiple imputations, we randomly draw five plausible values from the pool of the 10 closest neighbors in terms of the predicted wage. See Weiss (2012) for details. The percentage of missing values is very similar among firstborns (23.2 %) and later-borns (24.3 %). As shown in the Results section, our results do not depend on imputations or on the use of single versus multiple imputations.

Brunello et al. (2015) showed that estimates are broadly unaffected when they replace labor market experience with age and exclude education in the wage regressions used to generate both the end wage in each job and within-job earnings growth for individuals who have had more than one job.

Haider and Solon (2006), Böhlmark and Lindquist (2006), Brenner (2010), and Brunello et al. (2015) also assumed a constant real interest rate of 2 % to construct a measure of lifetime income. Bhuller et al. (2014) instead used an interest rate of 2.3 %. We also experiment with a 3 % discount rate with no qualitative change of results. We are grateful to Christoph Weiss for providing the codes required to compute earnings profiles and lifetime earnings from the third wave of the survey SHARE.

Brunello et al. (2015) validated this procedure by comparing predicted and actual wages in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) and found that predictions based on the methodology suggested in the text are quite accurate.

By selecting only individuals born from 1935 onward, we reduce the role of survivorship bias (see Modin 2002) and recall bias for older workers, reduce the weight of imputation, and also ensure that no individual in our sample entered the labor market before World War II.

Of course, household size at age 10 is less correlated with order of birth than is household size at birth. For the small minority of individuals for which this information was not available—around 2 % of our sample—we reconstruct sibship size using information on the number of siblings alive at the time of the first SHARE interview.

We recode the number of siblings so that the top category is 10 or more.

We exclude information such as the number of books in the household and housing facilities at age 10 because they could be affected by birth order, as suggested by De Haan et al. (2014).

As in BDS, we treat children without siblings as firstborns. However, a sensitivity analysis that excluded single children yielded very similar results. Results are not shown but are available from the authors upon request.

We obtain equivalent results when we consider earnings at age 25, 30, 40, and 50, but we prefer to use time spent in the labor market instead of age because age of entrance in the labor market could be endogenous.

BDS argued that “. . . in general, there are no genes for being a firstborn or a later-born so it is unlikely that the birth order effects we find have genetic or biological causes. . . .” (p. 20). De Haan et al. (2014) have recently questioned this assumption on the grounds that later-borns may face higher prenatal environmental risks because of increased levels of maternal antibody, which attack the development of the brain in utero.

Similar to Price (2008), we stop at a family size of four siblings because sample sizes for households with a higher number of siblings would be very small.

Detailed results by family size are available from the authors upon request.

Using a higher real interest rate (3 %) to compute lifetime earnings does not alter qualitatively the effect of the order of birth, which is estimated at –0.003 (standard error = 0.019). Table S2 in Online Resource 1 shows that our results are robust to controlling for the prevailing macroeconomic conditions in the country of the respondent at the time when the earnings are measured, using GDP growth. In this case, we cluster standard errors at the country-by-year level. Data on GDP growth by country and year are from the Maddison Tables (http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/oriindex.htm).

Because 10.2 % and 8.7 % of later-borns are white-collar workers and workers in the public sector, respectively, the estimated percentage difference is equivalent to a 25.5 and a 35 % gap. Our results are qualitatively unaltered when we add education as an additional control.

Cappellari (2002) and Hartog and Oosterbeek (1993) showed that age earnings profiles are steeper in the private sector in Italy and the Netherlands, respectively. Conversely, Dustmann and Van Soest (1998) showed that profiles are steeper in the German public sector, and Disney et al. (2009) presented mixed evidence for the United Kingdom. Following Zajonc (1976), we speculate that firstborns may have had to share with parents the responsibility of raising younger siblings. This could have induced them to invest effort and parental networks to locate a good and stable first job and to keep it longer. In support of this view, Table S5 in Online Resource 1 shows that the probability of a firstborn landing a white-collar or a public-sector job as a first job increases with the number of siblings.

Table S6 in Online Resource 1 compares stayers and movers after 10 and 15 years in the labor market. The table shows that stayers (more likely to be firstborns) start their second job (if ever) at an average age of 39, more than 17 years later than movers.

We find similar results 15 years after entry in the labor market. We also examine whether being firstborn had any effect on experiencing unemployment but find no evidence that this is the case.

In his extensive monograph “Born to Rebel,” Sulloway (1996) showed descriptive evidence that firstborns have always been more prone to support the status quo and that later-borns have been more willing to challenge it. In addition, later-borns are more likely to play risky sports than firstborns (Nisbett 1968) and when playing the same sport are more likely to carry out riskier moves (Sulloway and Zweigenhaft 2010). Other research has shown that being a later-born positively affects the number of times a college student was arrested (Zweigenhaft and Von Ammon 2000). These findings mirror general beliefs about personality traits of first and later-borns (Herrera et al. 2003). Finally, Healey and Ellis (2007) found differences in conscientiousness and openness to new experiences across birth order by using family fixed-effect models.

Let us define w 0, w 1, U′, U″, and RR, respectively, as the current wage, the wage offer, the first and second derivatives of the utility function, and the index of relative risk aversion. Using a second-order Taylor approximation of U(w 1 ) around w 0, we see that a wage offer is accepted and mobility occurs when

$$ \frac{w_1-{w}_0}{w_0}>-\frac{2U^{\prime}\left({w}_0\right)}{U^{\prime\prime}\left({w}_0\right){w}_0}=\frac{2}{RR}. $$If the distribution of expected wage gains \( \frac{w_1-{w}_0}{w_0} \) is not too different for firstborns and later-borns, both turnover and observed earnings growth are lower for the former, who have higher values of RR.

The learning model could also be augmented by positing that birth order captures other individual attitudes and noncognitive skills accumulated before schooling (see Cunha and Heckman 2007; Heckman et al. 2006). However, this extension would require that employers could observe birth order, which seems unlikely in the presence of rules prohibiting discrimination.

To see this, define S i = π0 + π1 O i + ξ i and substitute this in Eq. (7). We obtain that the marginal effect of being firstborn on earnings is b 1π1 − d 1 r 1.

References

Allen, D. G., Weeks, K. P., & Moffitt, K. R. (2005). Turnover intentions and voluntary turnover: The moderating roles of self-monitoring, locus of control, proactive personality, and risk aversion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 980–990.

Altonji, J. G., & Pierret, C. R. (2001). Employer learning and statistical discrimination. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 313–350.

Bagger, J., Birchenall, J. A., Mansour, H., & Urzúa, S. (2013). Education, birth order, and family size (NBER Working Paper No. 19111). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Barclay, K., & Kolk, M. (2015). Birth order and mortality: A population-based cohort study. Demography, 52, 613–639.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). Interaction between quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, S279–S288.

Behrman, J. R., & Taubman, P. (1986). Birth order, schooling, and earnings. Journal of Labor Economics, 4, S121–S145.

Belzil, C., & Leonardi, M. (2007). Can risk aversion explain schooling attainments? Evidence from Italy. Labour Economics, 14, 957–970.

Bhuller, M., Mogstad, M., & Salvanes, K. G. (2014). Life cycle earnings, education premiums and internal rates of return (IZA Discussion Paper No. 8316). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Bingley, P., & Martinello, A. (2014). Measurement error in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe: A validation study with administrative data for education level, income and employment (SHARE Working Paper No. 16-2014). Retrieved from http://www.share-project.org/publications/share-working-paper-series.html

Björklund, A., & Jäntti, M. (2012). How important is family background for labor-economic outcomes? Labour Economics, 19, 465–474.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2005). The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 669–700.

Böhlmark, A., & Lindquist, M. J. (2006). Life cycle variations in the association between current and lifetime income: Replication and extension for Sweden. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 879–896.

Bonin, H., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2007). Cross-sectional earnings risk and occupational sorting: The role of risk attitudes. Labour Economics, 14, 926–937.

Brenner, J. (2010). Life-cycle variations in the association between current and lifetime earnings: Evidence for German natives and guest workers. Labour Economics, 17, 392–406.

Brunello, G., Weber, G., & Weiss, C. T. (2015). Books are forever: Early life conditions, education and lifetime earnings in Europe. Economic Journal. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12307

Cappellari, L. (2002). Earnings dynamics and uncertainty in Italy: How do they differ between the private and public sectors? Labour Economics, 9, 477–496.

Clark, A., & Postel-Vinay, F. (2009). Job security and job protection. Oxford Economic Papers, 61, 207–239.

Cunha, F., & Heckman, J. J. (2007). The technology of skill formation. American Economic Review, 97, 31–47.

De Haan, M. (2010). Birth order, family size and educational attainment. Economics of Education Review, 29, 576–588.

De Haan, M., Plug, E., & Rosero, J. (2014). Birth order and human capital development: Evidence from Ecuador. Journal of Human Resources, 49, 359–392.

Disney, R., Emmerson, C., & Tetlow, G. (2009). What is a public sector pension worth? Economic Journal, 119, F517–F535.

Dustmann, C., & van Soest, A. (1998). Public and private sector wages of male workers in Germany. European Economic Review, 42, 1417–1441.

Haider, S., & Solon, G. (2006). Life cycle variation in the association between current and lifetime earnings. American Economic Review, 96, 1308–1320.

Hartog, J., & Oosterbeek, H. (1993). Public and private sector wages in the Netherlands. European Economic Review, 37, 97–114.

Hartog, J., Plug, E., Diaz Serrano, L., & Vieria, J. (2003). Risk compensation in wage—A replication. Empirical Economics, 28, 639–647.

Havari, E., & Savegnago, M. (2013). The causal effect of parents’ schooling on children’s schooling in Europe. A new IV approach (Working Paper No. 30/2013). Venice, Italy: Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Department of Economics.

Healey, M. D., & Ellis, B. J. (2007). Birth order, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Tests of the family-niche model of personality using a within-family methodology. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 28, 55–59.

Heckman, J. J., Stixrud, J., & Urzua, S. (2006). The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior (NBER Working Paper No. 12006). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Herrera, N. C., Zajonc, R. B., Wieczorkowska, G., & Cichomski, B. (2003). Beliefs about birth rank and their reflection in reality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 142–150.

Hogan, V., & Walker, I. (2007). Education choice under uncertainty: Implications for public policy. Labour Economics, 14, 894–912.

Hotz, V. J., & Pantano, J. (2015). Strategic parenting, birth order and school performance. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 911–936.

Kantarevic, J., & Mechoulan, S. (2006). Birth order, educational attainment, and earnings: An investigation using the PSID. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 755–777.

Kessler, D. (1991). Birth order, family size, and achievement: Family structure and wage determination. Journal of Labor Economics, 9, 413–426.

Lehmann, J. Y. K., Nuevo-Chiquero, A., & Vidal-Fernández, M. (2013). Explaining the birth order effect: The role of prenatal and early childhood investments (IZA Discussion Paper No. 6755). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Mantell, R. (2011). How birth order can affect your job salary. Retrieved from www.marketwatch.com/story/how-birth-order-can-affect-your-job-salary-2011-09-23

Mazzonna, F. (2013). The effect of education on old age health and cognitive abilities—Does the instrument matter? Unpublished manuscript, Munich Economics of Ageing at the Max-Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy, Munich, Germany.

Modin, B. (2002). Birth order and mortality: A life-long follow-up of 14,200 boys and girls born in early 20th century Sweden. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 1051–1064.

Murphy, K. M., & Welch, F. (1990). Empirical age-earnings profiles. Journal of Labour Economics, 8, 202–229.

Nisbett, R. E. (1968). Birth order and participation in dangerous sports. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 351–353.

Olneck, M. R., & Bills, D. B. (1979). Family configuration and achievement: Effects of birth order and family size in a sample of brothers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42, 135–148.

Oreopoulos, P., von Wachter, T., & Heisz, A. (2012). The short-and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4, 1–29.

Price, J. (2008). Parent-child quality time: Does birth order matter? Journal of Human Resources, 43, 240–265.

Shaw, K. L. (1996). An empirical analysis of risk aversion and income growth. Journal of Labor Economics, 14, 626–653.

Sulloway, F. J. (1996). Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Sulloway, F. J. (2007). Birth order and sibling competition. In R. Dunbar & L. Barrett (Eds.), Oxford handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 297–311). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Sulloway, F. J., & Zweigenhaft, R. L. (2010). Birth order and risk taking in athletics: A meta-analysis and study of major league baseball players. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 402–416.

Tamborini, C. R., Kim, C., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Education and lifetime earnings in the United States. Demography, 52, 1383–1407.

Wang, X. T., Kruger, D. J., & Wilke, A. (2009). Life history variables and risk-taking propensity. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30, 77–84.

Weiss, C. T. (2012). Two measures of lifetime resources for Europe using SHARELIFE (SHARE Working Paper Series 06-2012). Retrieved from www.share-project.org

Zajonc, R. B. (1976). Family configuration and intelligence. Science, 291, 227–236.

Zweigenhaft, R. L., & Von Ammon, J. (2000). Birth order and civil disobedience: A test of Sulloway’s “born to rebel” hypothesis. Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 624–627.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Editor, an anonymous referee, Massimiliano Bratti, Lorenzo Cappellari, Hessel Oosterbeek, Erik Plug, Olmo Silva, Guglielmo Weber, Christoph Weiss; and the audience at seminars in Catanzaro (IWAEE), Padova, Reus, and Rome (Brucchi Luchino) for comments and suggestions. This paper uses data from SHARELIFE release 1, as of November 24, 2010, and SHARE release 2.5.0, as of May 24, 2011. The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through the 5th framework programme (project QLK6-CT-2001- 00360 in the thematic programme Quality of Life), through the 6th framework programme (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT-2006 062193, COMPARE, CIT5-CT-2005-028857, and SHARELIFE, CIT4-CT-2006-028812), and through the 7th framework programme (SHARE-PREP, 211909 and SHARE-LEAP, 227822). Financial support from the POPA_EHR Strategic Project of the University of Padova is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 337 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertoni, M., Brunello, G. Later-borns Don’t Give Up: The Temporary Effects of Birth Order on European Earnings. Demography 53, 449–470 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0454-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0454-1