Abstract

Background

Although compassionate care is considered a cornerstone of quality palliative care, there is a paucity of valid and reliable measures to study, assess, and evaluate how patients experience compassion/compassionate care in their care.

Objective

The aim was to develop a patient-reported compassion measure for use in research and clinical practice with established content-related validity evidence for the items, question stems, and response scale.

Methods

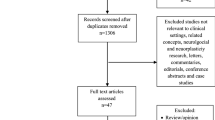

Content validation for an initial 109 items was conducted through a two-round modified Delphi technique, followed by cognitive interviews with patients. A panel of international Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and a Patient Advisory Group (PAG) assessed the items for their relevancy to their associated domain of compassion, yielding an Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI), which was used to determine content modifications. The SMEs and the PAG also provided narrative feedback on the clarity, flow, and wording of the instructions, questions, and response scale, with items being modified accordingly. Cognitive interviews were conducted with 16 patients to further assess the clarity, comprehensibility, and readability of each item within the revised item pool.

Results

The first round of the Delphi review produced an overall CVI of 72% among SMEs and 80% among the PAG for the 109 items. Delphi panelists then reviewed a revised measure containing 84 items, generating an overall CVI of 84% for SMEs and 86% for the PAG. Sixty-eight items underwent further testing via cognitive interviews with patients, resulting in an additional 14 items being removed.

Conclusions

Having established this initial validity evidence, further testing to assess internal consistency, test–retest reliability, factor structure, and relationships to other variables is required to produce the first valid, reliable, and clinically informed patient-reported measure of compassion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Weldring T, Smith S. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–68.

Lakhani A. Indicators for measuring patient experience. 2013. https://www.patientlibrary.net/tempgen/105346.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2018.

Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017;14(4):137–44.

Sinclair S, McClement S, Raffin-Bouchal S, et al. Compassion in health care: an empirical model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:193–203.

Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. London: The Stationary Office; 2013.

Heyland D, Dodek P, Rocker G, Canadian Researchers End-of-Life Network (CARENET), et al. What matters most in end-of- life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):627–33.

Crowther J, Wilson K, Horton S, et al. Compassion in healthcare: lessons from a qualitative study of the end of life care of people with dementia. J R Soc Med. 2013;106(12):492–7.

Lown B, Rosen J, Marttila J. An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:1772–8.

Willis L. Raising the bar: the shape of caring review. London: Health Education England; 2015.

Maclean R. The Vale of Leven Hospital Inquiry. Edinburgh: APS Group; 2014.

National Health Service Commissioning Board Chief Nursing Officer and Department of Health Chief Nursing Adviser. Compassion in practice: nursing, midwifery and care staff. Our vision and strategy. Leeds: Department of Health. 2012.

Reader T, Gillespie A. Patient neglect in healthcare institutions: a systematic review and conceptual model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:156–70.

Sinclair S, Russell LB, Hack TF, et al. Measuring compassion in healthcare: a comprehensive and critical review. Patient. 2016;10(4):389–405.

Sinclair S, Beamer K, Hack TF, et al. Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: a grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliat Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316663499.

Sinclair S, Jaggi P, Hack TF, et al. A practical guide for item generation in measure development: insights from the development of a patient-reported experience measure of compassion. J Nurs Meas. 2020 (In press).

DeVellis R. Scale development: theory and applications. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2003.

Saris W. Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. New York: Wiley. 2014.

Hinkin T. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires, vol. 1. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 104–121.

Sinclair S, Jaggi P, Hack TF, et al. Assessing the credibility and transferability of the patient compassion model in non-cancer palliative populations. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:108.

Lynn M. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382–5.

Yaghmale F. Content validity and its estimation. J Med Educ. 2003;3(1):25–7.

Messick S. Validity. In: Linn RL, editor. The American Council on Education/Macmillan series on higher education. Educational measurement. Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc; American Council on Education. 1989. p. 13–103.

Sireci SG. The construct of content validity. Soc Indic Res. 1998;45(1–3):83–117. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006985528729.

Burns K, Duffett M, Kho M, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys for clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179(3):245–52.

Hsu CS. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. Br Med J. 1995;311(7001):376–80.

Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. J Pain Symptom Manage BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:6–20.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. SPOR Support Units https://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45859.html. Accessed 11 Mar 2019.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Slocumb E, Cole F. A practical approach to content validation. Appl Nurs Res. 1991;4:192–5.

Grant J, Davis L. Selection and use of content experts for instrument development. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:269–74.

Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005.

Polit D, Beck C. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:489–97.

Polit D, Beck C, Owen S. Is the CVI and acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30:459–67.

Davis LL. Instrument review: getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl Nurs Res. 1992;5:194–7.

Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. Qualitative Research Practice. London: Sage; 2003. p. 219–262.

Rattray J, Jones M. Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(2):234–43.

Nichols P, Sugrue B. The lack of fidelity between cognitively complex constructs and conventional test development practice. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 1999;18:18–29.

Bowling A. Research methods in health. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997.

Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwisk R. Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care ScaleTM. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):1005–100.

Lee Y, Seomun G. Development and validation of an instrument to measure nurses’ compassion competence. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:76–82.

Burnell L, Agan D. Compassionate care can it be defined and measured? The development of the compassionate care assessment tool. Int J Caring Sci. 2013;6:180–7.

Collins D. Analysing and interpreting cognitive interview data: a qualitative approach. Quest 2007 Proceedings; 2007. pp. 64–73. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/QBank/Quest/2007/QUEST%202007%20Proceedings-all%20papers.pdf#page=74 Accessed 11 Mar 2019.

American Educational Research Association. American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: AERA; 2014.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their support in this study: the Subject Matter Experts, Dr. Mary Vachon, Dr. Nathan Consedine, Dr. Philip Larkin, Dr. Betty Ferrell, Dr. Stephen Post, Dr. Stephen Smith, Dr. Latha Chandran, and Dr. Antonio Fernando, and Mark Hall, Research Associate, Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary, for providing support with the data analysis.

Funding

This study was funded through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Scheme Grant (#364041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (1) made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; (2) were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) gave final approval of the version to be published and have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; and (4) agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors (SS, PJ, TFH, LR, SEM, LC, LES, and CL) declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB #17-0754).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinclair, S., Jaggi, P., Hack, T.F. et al. Initial Validation of a Patient-Reported Measure of Compassion: Determining the Content Validity and Clinical Sensibility among Patients Living with a Life-Limiting and Incurable Illness. Patient 13, 327–337 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00409-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00409-8