Abstract

Background

Consumers are more inclined than healthcare professionals (HCPs) to submit adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports, usually because of first-hand experience with an ADR. As consumer ADR reporting has led to important findings in other countries, the Turkish Pharmacovigilance Center (TUFAM) started accepting ADR reports directly from consumers.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to, for the first time in Turkey, review and compare ADR reports from consumers and HCPs.

Methods

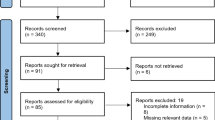

We identified and evaluated all ADR reports that were submitted by TUFAM to VigiBase between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2016 and fulfilled minimum reporting criteria. Minimum reporting criteria required an identifiable reporter, an identifiable patient, at least one suspected active substance/drug and at least one suspected adverse reaction. We compared ADRs submitted by either consumers or HCPs with respect to the reported sex of patients, the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms (PTs) used, designated medical event (DME) terms, the seriousness of the ADRs and the suspect drugs.

Results

We analyzed 9150 spontaneous ADR reports that fulfilled the minimum reporting criteria. Of these, 3141 were submitted by consumers and 6009 were submitted by HCPs. Annual reporting rates (RRs) and the number of consumer ADR reports showed an increasing trend over time. The male:female ratio was 0.85 for consumer reports and 0.76 for HCP reports. In total, 12 of the 20 most frequently used PTs were identical for both consumers and HCPs. For ADRs classified as serious, consumers submitted 33.3% and HCPs submitted 52.2%. Consumers used only ten Designated Medical Event (DME) terms while HCPs used 35 DME terms out of a total of 62 DME terms at least once. Consumers most frequently reported ADRs to nervous system drugs, whereas HCPs most frequently reported ADRs to anti-infective drugs for systemic use. Consumers most frequently reported ADRs linked to gastrointestinal disorders, whereas HCPs most frequently reported ADRs linked to skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders.

Conclusions

This is the first study to compare spontaneous ADR reports from consumers and HCPs in Turkey. Our analysis indicates the reporting of ADRs by both consumers and HCPs is increasing. We found not only similarities in the two groups regarding suspect drugs and classification terms used, but also prominent differences. Consumers and HCPs had 12 of the 20 most frequently used PTs in common, but the remaining eight PTs used by consumers differed from those used by HCPs. This probably reflects the effect an ADR can have on a consumer’s daily life. HCPs also reported more serious ADRs than did consumers. Consumer reports have a secondary contribution to ADR reporting, which might then be used to improve existing pharmacovigilance systems with the consumer’s perspective in mind.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions. WHO Drug Inf. 2000;14(4):211–15. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s2201e/s2201e.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2017.

George C. Reporting adverse drug reactions: a guide for healthcare professionals. London: British Medical Association; 2006.

Aagaard L, Nielsen LH, Hansen EH. Consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions. A retrospective analysis of the Danish Adverse Drug Rection Database from 2004 to 2006. Drug Saf. 2009;32(11):1067–74.

World Health Organization. Safety monitoring of medical products: reporting system for the general public. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2012. http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/EMP_ConsumerReporting_web_v2.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2017.

Robertson J, Newby DA. Low awareness of adverse drug reaction reporting systems: a consumer survey. MJA. 2013;199(10):684–6.

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/canada-vigilance-program.html. Accessed 18 Jul 2017.

van Hunsel F, Harmark L, Pal S, Olsson S, van Grootheest K. Experiences with adverse drug reaction reporting by patients. An 11-country survey. Drug Saf. 2012;35(1):45–60.

Herxheimer A, Crombag R, Alves TL. Direct patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: a fifteen-country survey & literatue review. Amsterdam: Health Action International; 2010.

Anderson TC, Krska J, Murphy E, Avery A, on behalf of the Yellow Card Study Collaboration. The importance of direct patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a patient perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):806–22.

Blenkinsopp A, Wilkie P, Wang M, Routledge PA. Patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a review of published literature and international experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;63(2):148–56.

McLernon DJ, Bond CM, Hannaford PC, Watson MC, Lee AJ, Hazell L, Avery A. Adverse drug reaction reporting in the UK. A retrospective observational comparison of yellow card reports submitted by patients and healthcare professionals. Drug Saf. 2010;33(9):775–88.

Avery AJ, Anderson C, Bond CM, et al. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK “Yellow Card Scheme”: literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(20):i-234.

Santos A. Direct Patient Reporting in the European Union. A Snapshot of Reporting Systems in Seven Member States, 16 September 2015. http://haiweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Direct-Patient-Reporting-in-the-EU.pdf. Accessed 3 Apr 2017.

Directive 2010/84/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010 amending, as regards pharmacovigilance. Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use [online]. http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol1/dir_2010_84/dir_2010_84_en.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2017.

Medawar C, Herxheimer A, Bell A, Jofre S. Paroxetine, Panorama and user reporting of ADRs: consumer intelligence matters in clinical practice and post-marketing drug surveillance. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2002;15:161–9.

van Grootheest K, de Graaf L, de Jong-van den Berg LTW. Consumer adverse drug reaction reporting: a new step in pharmacovigilance? Drug Saf. 2003;26(4):211–7.

van Hunsel F, Passier A, van Grootheest K. Comparing patients’ and healthcare professionals’ ADR reports after media attention: the broadcast of a Dutch television programme about the benefits and risks of statins as an example. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(5):558–64.

Härmark L, van Hunsel F, Grundmark B. ADR reporting by the general public: lessons learnt from the Dutch and Swedish Systems. Drug Saf. 2015;38:337–47.

Rolfes L, Wilkes S, van Hunsel F, van Puijenbroek E, van Grootheest K. Important information regarding reporting of adverse drug reactions:a qualitative study. IJPP. 2014;22:231–3.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Wilkes S, van Grootheest K, van Puijenbroek E. Adverse drug reaction reports of patients and healthcare professionals-differences in reported information. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:152–8.

Härmark L, Raine J, Leufkens H, Edwards IR, Moretti U, Sarinic VM, Kant A. Patient-reported safety information:a renaissance of pharmacovigilance? Drug Saf. 2016;39(10):883–90.

Banovac M, Candore G, Slattery J, Houÿez F, Haerry D, Genov G, Arlett P. Patient reporting in the EU: analysis of EudraVigilance data. Drug Saf. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0534-1.

Inácio P, Cavaco A, Airaksinen M. The value of patient reporting to the pharmacovigilance system:a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:227–46.

Hughes CM. Monitoring self-medication. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2003;2(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2.1.1.

Herxheimer A, Mintzes. Antidepressants and adverse effects in young patients: uncovering the evidence. CMAJ. 2004;170(4):487–9.

Mitchell AS, Henry DA, Sanson-Fischer R, O’Connell DL. Patients as a direct source of information on adverse drug reactions. BMJ. 1988;297:891–3.

Egberts TCG, Smulders M, Koning FHP, Meyboom RHB, Leufkens HGM. Can adverse drug reactions be detected earlier? A comparison of reports by patients and professionals. BMJ. 1996;313:530–1.

van Hunsel F, Talsma A, van Puijenbroek E, de de Jong-van den Berg L, van Grootheest K. The proportion of patient reports of suspected ADRs to signal detection in the Netherlands: case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:286–91.

van Hunsel F, de Waal S, Härmark L. The contribution of direct patient reported ADRs to drug safety signals in the Netherlands from 2010–2015. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4236.

Aagaard L, Hansen EH. Consumers’ reports of suspected adverse drug reactions volunteered to a consumer magazine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;69(3):317–8.

van Hunsel F, van Puijenbroek E, de de Jong-van den Berg L, van Grootheest K. Grootheest K. Media attention and the influence on the reporting odds ratio in disproportionality analysis: an example of partient reporting of statins. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:26–32.

van Grootheest K, de Jong-van den Berg L. Patients’ role in reporting adverse drug reactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3(4):363–8.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, van der Linden L, Taxis K, van Puijenbroek E. The quality of clinical information in adverse drug reaction reports by patients and healthcare professionals: a retrospective comparative analysis. Drug Saf. 2017;40(7):607–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0530-5.

Bongard V, Ménard-Taché S, Bagheri H, Kabiri K, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Perception of the risk of adverse drug reactions: differences between health professionals and non health professionals. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:433–6.

Jarernsiripornkul N, Krska J, Capps PAG, Richards RME, Lee A. Patient reporting of potential adverse drug reactions: a methodological study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:318–25.

Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use (Off J L. 2004;311:67–128).

Beşeri Tıbbi Ürünlerin Güvenliğinin İzlenmesi ve Değerlendirilmesi Hakkında Yönetmelik, 22 Mart 2005. http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2005/03/20050322-7.htm. Accessed 22 Jul 2017.

Pal SN, Olsson S, Brown EG. The monitoring medicines project: a multinational pharmacovigilance and public health project. Drug Saf. 2015;38:319–28.

İlaçların Güvenliliği Hakkında Yönetmelik, 15 Nisan 2014. http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2014/04/20140415-6.htm. Accessed 22 Jul 2017.

Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. https://www.whocc.no/filearchive/publications/1_2013guidelines.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2017.

ICH harmonised tripartite guideline. Clinical safety data management:definitions and standards for expedited reporting E2A. https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E2A/Step4/E2A_Guideline.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr 2017.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Designated medical event (DME) list 17 August 2016. EMA/557113/2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/includes/document/document_detail.jsp?webContentId=WC500212079&mid=WC0b01ac058009a3dc. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Turkish Statistical Institute. Main statistics: population and demography. 2016. http://www.turkstat.gov.tr. Accessed 16 May 2017.

Köse MR et al. General Directorate of Health Research, The Ministry of Health of Turkey Health Statistics Yearbook 2016, Ankara, 2017.

de Langen J, van Hunsel F, Passier A, de de Jong-van den Berg L, van Grootheest K. Adverse drug reaction reporting by patients in the Netherlands. Three years of experience. Drug Saf. 2008;31(6):515–24.

Tharpe N. Adverse drug reactions in women’s health care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:205–13.

Stabile S, Ruggiero F, Taurasi F, Russo L, Vigano M, Borin F. Gender difference as risk factor for adverse drug reactions: data analysis in Salvini Hospital. PhOL. 2014;2:75–80.

Yu Y, Chen J, Li D, Wang L, Wang W, Liu H. Systematic analysis of adverse event reports for sex differences in adverse drug events. Sci Rep. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24955.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ali Alkan and Hakkı Gürsöz for their continuous support, Nergiz Temiz Nemutlu, Filiz Özel, and Hacer Ebru Aydoğan’s for collecting the data, and Onur Can Serinyel for his support on graphic design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Conflict of ınterest

NDemet Aydınkarahaliloğlu, Emel Aykaç, Özge Atalan, and Nilcan Demir are employed by the Turkish Medicines and Medical Devices Agency. They have no other conflicts of interest. Mutlu Hayran has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aydınkarahaliloğlu, N.D., Aykaç, E., Atalan, Ö. et al. Spontaneous Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions by Consumers in Comparison with Healthcare Professionals in Turkey from 2014 to 2016. Pharm Med 32, 353–364 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-018-0244-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-018-0244-8