Abstract

Background

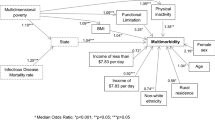

Disparities in adult morbidity and mortality may be rooted in patterns of biological dysfunction in early life. We sought to examine the association between pathogen burden and a cumulative deficits index (CDI), conceptualized as a pre-clinical marker of an unhealthy biomarker profile, specifically focusing on patterns across levels of social disadvantage.

Methods

Using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004 wave (aged 20–49 years), we examined the association of pathogen burden, composed of seven pathogens, with the CDI. The CDI comprised 28 biomarkers corresponding to available clinical laboratory measures. Models were stratified by race/ethnicity and education level.

Results

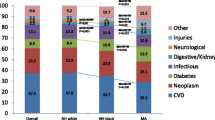

The CDI ranged from 0.04 to 0.78. Nearly half of Blacks were classified in the high burden pathogen class compared with 8% of Whites. Among both Mexican Americans and other Hispanic groups, the largest proportion of individuals were classified in the common pathogens class. Among educational classes, 19% of those with less than a high school education were classified in the high burden class compared with 7% of those with at least a college education. Blacks in the high burden pathogen class had a CDI 0.05 greater than those in the low burden class (P < 0.05). Whites in the high burden class had a CDI only 0.03 greater than those in the low burden class (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Our findings suggest there are significant social disparities in the distribution of pathogen burden across race/ethnic groups, and the effects of pathogen burden may be more significant for socially disadvantaged individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mann KD, et al. Differing lifecourse associations with sport-, occupational-and household-based physical activity at age 49–51 years: the Newcastle Thousand Families Study. Int J Publ Health. 2013;58(1):79–88.

Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–41.

Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. US disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–52.

Belsky DW, et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(30):E4104–10.

Williams DR, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annu Rev Sociol. 1995;21(1):349–86.

Geronimus AT. To mitigate, resist, or undo: addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):867–72.

Lantz PM, Lynch JW, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Mero RP, Musick MA, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health change in a longitudinal study of US adults: the role of health-risk behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(1):29–40.

Evans GW, Kantrowitz E. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23(1):303–31.

Hajat A, Diez-Roux AV, Adar SD, Auchincloss AH, Lovasi GS, O’Neill MS, et al. Air pollution and individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status: evidence from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(11–12):1325–33.

Juster R-P, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16.

Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–33.

Needham BL, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2015;26(4):528.

Noppert G, et al. Investigating pathogen burden in relation to a cumulative deficits index in a representative sample of US adults. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(15):1968–76.

King KE, Fillenbaum GG, Cohen HJ. A cumulative deficit laboratory test–based frailty index: personal and neighborhood associations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):1981–7.

Feinstein L, Douglas CE, Stebbins RC, Pawelec G, Simanek AM, Aiello AE. Does cytomegalovirus infection contribute to socioeconomic disparities in all-cause mortality? Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;158:53–61.

Itzhaki RF, Cosby SL, Wozniak MA. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease: the autophagy connection. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(1):1–4.

Roberts ET, Haan MN, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Cytomegalovirus antibody levels, inflammation, and mortality among elderly Latinos over 9 years of follow-up. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):363–71.

Nazmi A, et al. The influence of persistent pathogens on circulating levels of inflammatory markers: a cross-sectional analysis from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):706.

Epstein SE, Zhu J, Burnett MS, Zhou YF, Vercellotti G, Hajjar D Infection and atherosclerosis: potential roles of pathogen burden and molecular mimicry. Am Heart Assoc. 2000; 1417–1420.

Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Pawelec G, Melzer D, Dutta A, Aiello AE. Seropositivity to cytomegalovirus, inflammation, all-cause and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the United States. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16103.

Schmaltz HN, Fried LP, Xue QL, Walston J, Leng SX, Semba RD. Chronic cytomegalovirus infection and inflammation are associated with prevalent frailty in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):747–54.

Pawelec G, McElhaney JE, Aiello AE, Derhovanessian E. The impact of CMV infection on survival in older humans. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(4):507–11.

Pawelec G, Akbar A, Caruso C, Solana R, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Wikby A. Human immunosenescence: is it infectious? Immunol Rev. 2005;205(1):257–68.

Simanek A, et al. Unpacking the ‘black box’of total pathogen burden: is number or type of pathogens most predictive of all-cause mortality in the United States? Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(12):2624–34.

Bray BC, Lanza ST, Tan X. Eliminating bias in classify-analyze approaches for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 2015;22(1):1–11.

Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(Supplement_1):S3–S28.

McQuillan GM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the seroprevalence of 6 infectious diseases in the United States: data from NHANES III, 1988–1994. Am J Publ Health. 2004;94(11):1952–8.

Malaty HM, el-Kasabany A, Graham DY, Miller CC, Reddy SG, Srinivasan SR, et al. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: a follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359(9310):931–5.

Meier HC, et al. Early life socioeconomic position and immune response to persistent infections among elderly Latinos. Soc Sci Med. 2016;166:77–85.

Dowd JB, Bosch JA, Steptoe A, Jayabalasingham B, Lin J, Yolken R, et al. Persistent herpesvirus infections and telomere attrition over 3 years in the Whitehall II cohort. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(5):565–72.

Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Biomarkers of human immunosenescence: impact of Cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(4):440–5.

Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202(5):673–85.

Pourgheysari B, Khan N, Best D, Bruton R, Nayak L, Moss PAH. The cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T-cell response expands with age and markedly alters the CD4+ T-cell repertoire. J Virol. 2007;81(14):7759–65.

Vescovini R, Biasini C, Fagnoni FF, Telera AR, Zanlari L, Pedrazzoni M, et al. Massive load of functional effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against cytomegalovirus in very old subjects. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):4283–91.

Dowd JB, Zajacova A, Aiello A. Early origins of health disparities: burden of infection, health, and socioeconomic status in US children. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(4):699–707.

Dowd JB, Palermo TM, Aiello AE. Family poverty is associated with cytomegalovirus antibody titers in US children. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):5–10.

Gares V, et al. The role of the early social environment on Epstein Barr virus infection: a prospective observational design using the Millennium Cohort Study. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(16):3405–12.

Glaser R. Stress-associated immune dysregulation and its importance for human health: a personal history of psychoneuroimmunology. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(1):3–11.

Glaser R, Friedman SB, Smyth J, Ader R, Bijur P, Brunell P, et al. The differential impact of training stress and final examination stress on herpesvirus latency at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Brain Behav Immun. 1999;13(3):240–51.

Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Chronic stress modulates the virus-specific immune response to latent herpes simplex virus type 1. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):78–82.

McDade TW, Stallings JF, Angold A, Costello EJ, Burleson M, Cacioppo JT, et al. Epstein-Barr virus antibodies in whole blood spots: a minimally invasive method for assessing an aspect of cell-mediated immunity. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(4):560–8.

Herbert TB, Cohen S. Stress and immunity in humans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(4):364–79.

Mehta SK, Stowe RP, Feiveson AH, Tyring SK, Pierson DL. Reactivation and shedding of cytomegalovirus in astronauts during spaceflight. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(6):1761–4.

Esterling BA, Antoni MH, Kumar M, Schneiderman N. Defensiveness, trait anxiety, and Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen antibody titers in healthy college students. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):132–9.

Martin CL, Kane JB, Miles GL, Aiello AE, Harris KM. Neighborhood disadvantage across the transition from adolescence to adulthood and risk of metabolic syndrome. Health Place. 2019;57:131–8.

Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:258–76.

Goodman E, McEwen BS, Dolan LM, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler NE. Social disadvantage and adolescent stress. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(6):484–92.

Friedman EM, Herd P. Income, education, and inflammation: differential associations in a national probability sample (the MIDUS study). Psychosom Med. 2010;72(3):290–300.

Pollitt R, et al. Cumulative life course and adult socioeconomic status and markers of inflammation in adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(6):484–91.

Fagundes CP, Bennett JM, Alfano CM, Glaser R, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, et al. Social support and socioeconomic status interact to predict Epstein-Barr virus latency in women awaiting diagnosis or newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):11–9.

Janicki-Deverts D, Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Marsland AL, Bosch J. Childhood environments and cytomegalovirus serostatus and reactivation in adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;40:174–81.

Prather AA, et al. Sleep habits and susceptibility to upper respiratory illness: the moderating role of subjective socioeconomic status. Ann Behav Med. 2016;51(1):137–46.

Cohen S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ, Adler N, Treanor JJ, Turner RB. Objective and subjective socioeconomic status and susceptibility to the common cold. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):268–74.

Stebbins RC, Noppert GA, Aiello AE, Cordoba E, Ward JB and Feinstein L. Persistent Socioeconomic and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pathogen Burden in the United States, 1999-2014. Epidemiology and Infection., 2019. In press.

Funding

G.A. Noppert received support from the National Institute on Aging through Duke University (grant number 5 T32-AG000029-41), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute of Child Health and Human Develpoment through the Unversity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (grant number T32-HD-091058), and the National Institute on Aging through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (grant number K99AG0627-01A1). A.M.O'Rand received support from the National Institute on Aging through the Duke Center for Population Health and Aging (grant number P30 AG034424).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Responsibilities of Authors

This manuscript has not been submitted to more than one journal for simultaneous consideration and has not been published previously. No data have been fabricated or manipulated to support the conclusions. Consent to submit has been received explicitly from all co-authors. Authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 77.4 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noppert, G.A., Aiello, A.E., O’Rand, A.M. et al. Race/Ethnic and Educational Disparities in the Association Between Pathogen Burden and a Laboratory-Based Cumulative Deficits Index. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 7, 99–108 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00638-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00638-0