Abstract

Working memory is a core cognitive system that is thought to support many forms of complex cognition. Mindfulness meditation has shown promise in improving the functioning of the working memory system, but no study has thoroughly tested its benefits by using a well-controlled study design (i.e., using multiple, valid outcome measures and an active, adaptive control group). The main goal of the current study was to more rigorously examine the effects of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity. This was done by comparing 2 weeks of focused attention mindfulness meditation training to active, adaptive cognitive training regarding improvement on multiple, valid indicators of working memory capacity that were different from the tasks participants trained on. The results of the present experiment suggest that 2 weeks of focused attention mindfulness meditation training does not improve working memory capacity when controlling for non-specific effects. Future interventions using similar well-controlled study designs can consider using longer duration, more frequent, or alternative styles of mindfulness meditation training to potentially enhance working memory capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Initially, $20 was offered to all participants for completing the 10th lab session. To recruit additional participants before the close of the semester, payment for completing the 10th lab session was increased to $30 for all participants. 53 participants completed the study when receiving $20, 12 participants completed the study when receiving $30 dollars.

Inclusion of this participant’s posttest OSPAN raw score into their posttest working memory capacity composite score changed the repeated measures ANOVA test of within-subjects contrasts main effect of time to a non-significant value, F(1, 63) = 3.953, p = .051, ηp2 = .059. This score inclusion did not change the results of the paired samples t tests examining within-group changes on the working memory capacity composite from pretest to posttest; only the mindfulness training group had a significantly different posttest from their pretest. Cohen’s d for the mindfulness training group’s pretest to posttest difference changed to d = .42.

As the time by group interaction indicated, the improvement in the mindfulness training group was not significantly different than the improvement in the cognitive training group. The results of the paired samples t tests should not suggest that in this study, mindfulness training improved working memory capacity whereas cognitive training did not. The rationale for and interpretation of these exploratory tests are detailed in the Data Analysis and Discussion sections.

Given the near-ceiling accuracy, one may question whether the executive tasks were challenging enough to induce adaptation and expectations of cognitive improvement. Recall, adaptation on these tasks required participants to increase their speed while maintaining high accuracy.

The amount of mindfulness meditation outside of class may have ranged from 1 h 20 min to 3 h 30 min. Mrazek et al. stated that participants were instructed to practice mindfulness meditation for 10 min per day outside of class. It was not stated whether this meant a low estimate of the 8 days of in-class training or a high estimate of 21 days between the start of training and posttests. Additionally, it was not reported what amount of mindfulness meditation practice occurred outside of the in-class meditation time.

It should be noted that the digit span backwards test used to assess working memory in this study was found to load on a short-term memory factor instead of a working memory capacity factor in Engle et al. (1999).

References

Banks, J. B., Welhaf, M. S., & Srour, A. (2015). The protective effects of brief mindfulness meditation training. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 277–285.

Bennike, I. H., Wieghorst, A., & Kirk, U. (2017). Online-based mindfulness training reduces behavioral markers of mind wandering. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1, 1–10.

Britton, W. B., Davis, J. H., Loucks, E. B., Barnes, P., Cullen, B. H., Reuter, L., Rando, A., Rahrig, H., Lipsky, J., & Lindahl, J. R. (2017). Dismantling mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: creation and validation of 8-week focused attention and open monitoring interventions within a 3-armed randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.010

Chambers, R., Lo, B. C. Y., & Allen, N. B. (2008). The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(3), 303–322.

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 449–464.

Chooi, W. T., & Thompson, L. A. (2012). Working memory training does not improve intelligence in healthy young adults. Intelligence, 40(6), 531–542.

Conway, A. R., & Kovacs, K. (2013). Individual differences in intelligence and working memory: a review of latent variable models. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 58, 233–270.

Conway, A. R., Kane, M. J., Bunting, M. F., Hambrick, D. Z., Wilhelm, O., & Engle, R. W. (2005). Working memory span tasks: a methodological review and user’s guide. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(5), 769–786.

Conway, A. R., Jarrold, C., Kane, M. J., Miyake, A., & Towse, J. N. (2007). Variation in working memory: an introduction. Variation in Working Memory, 3–17.

Engle, R. W. (2002). Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 19–23.

Engle, R. W., Tuholski, S. W., Laughlin, J. E., & Conway, A. R. (1999). Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: a latent-variable approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(3), 309–331.

Foroughi, C. K., Monfort, S. S., Paczynski, M., McKnight, P. E., & Greenwood, P. M. (2016). Placebo effects in cognitive training. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(27), 7470–7474.

Goghari, V. M., & Lawlor-Savage, L. (2017). Comparison of cognitive change after working memory training and logic and planning training in healthy older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 39.

Harrison, T. L., Shipstead, Z., Hicks, K. L., Hambrick, D. Z., Redick, T. S., & Engle, R. W. (2013). Working memory training may increase working memory capacity but not fluid intelligence. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2409–2419.

Hollis, R. B., & Was, C. A. (2016). Mind wandering, control failures, and social media distractions in online learning. Learning and Instruction, 42, 104–112.

Isbel, B., & Summers, M. J. (2017). Distinguishing the cognitive processes of mindfulness: developing a standardised mindfulness technique for use in longitudinal randomised control trials. Consciousness and Cognition, 52, 75–92.

Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., & Perrig, W. J. (2008). Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(19), 6829–6833.

Jaušovec, N., & Jaušovec, K. (2012). Working memory training: improving intelligence–changing brain activity. Brain and Cognition, 79(2), 96–106.

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., Kiyonaga, A., Wong, L., & Gelfand, L. (2010). Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion, 10(1), 54–64.

Jha, A. P., Witkin, J. E., Morrison, A. B., Rostrup, N., & Stanley, E. (2017). Short-form mindfulness training protects against working memory degradation over high-demand intervals. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 154–171.

Johnson, S., Gur, R. M., David, Z., & Currier, E. (2015). One-session mindfulness meditation: a randomized controlled study of effects on cognition and mood. Mindfulness, 6(1), 88–98.

Kane, M. J., Conway, A. R., Hambrick, D. Z., & Engle, R. W. (2007). Variation in working memory capacity as variation in executive attention and control. Variation in working memory, 1, 21–48.

Klingberg, T. (2010). Training and plasticity of working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(7), 317–324.

Knauff, M., & Wolf, A. G. (2010). Complex cognition: the science of human reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163–169.

Lutz, A., Jha, A. P., Dunne, J. D., & Saron, C. D. (2015). Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. American Psychologist, 70(7), 632–658.

McNamara, D. S., & Scott, J. L. (2001). Working memory capacity and strategy use. Memory & Cognition, 29(1), 10–17.

McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2009). Conducting the train of thought: working memory capacity, goal neglect, and mind wandering in an executive-control task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(1), 196–204.

Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 49(2), 270–291.

Morrison, A. B., Goolsarran, M., Rogers, S. L., & Jha, A. P. (2014). Taming a wandering attention: short-form mindfulness training in student cohorts. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 897. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00897

Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24(5), 776–781.

Quach, D., Mano, K. E. J., & Alexander, K. (2016). A randomized controlled trial examining the effect of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(5), 489–496.

Redick, T. S., Broadway, J. M., Meier, M. E., Kuriakose, P. S., Unsworth, N., Kane, M. J., & Engle, R. W. (2012). Measuring working memory capacity with automated complex span tasks. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 164–171.

Redick, T. S., Shipstead, Z., Harrison, T. L., Hicks, K. L., Fried, D. E., Hambrick, D. Z., Kane, M., & Engle, R. W. (2013). No evidence of intelligence improvement after working memory training: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 359.

Semple, R. J. (2010). Does mindfulness meditation enhance attention? A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 1(2), 121–130.

Shipstead, Z., Hicks, K. L., & Engle, R. W. (2012a). Cogmed working memory training: does the evidence support the claims? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(3), 185–193.

Shipstead, Z., Redick, T. S., & Engle, R. W. (2012b). Is working memory training effective? Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 628.

Shipstead, Z., Lindsey, D. R., Marshall, R. L., & Engle, R. W. (2014). The mechanisms of working memory capacity: primary memory, secondary memory, and attention control. Journal of Memory and Language, 72, 116–141.

Simons, D. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., Gathercole, S. E., Chabris, C. F., Hambrick, D. Z., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. (2016). Do “brain-training” programs work? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17(3), 103–186.

Teasdale, J. D., & Chaskalson, M. (2011a). How does mindfulness transform suffering? I: the nature and origins of dukkha. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(01), 89–102.

Teasdale, J. D., & Chaskalson, M. (2011b). How does mindfulness transform suffering? II: the transformation of dukkha. Contemporary Buddhism, 12(01), 103–124.

Thompson, T. W., Waskom, M. L., Garel, K. L. A., Cardenas-Iniguez, C., Reynolds, G. O., Winter, R., Chang, P., Pollard, K., Lala, N., Alvarez, G. A., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2013). Failure of working memory training to enhance cognition or intelligence. PLoS One, 8(5), e63614.

Turley-Ames, K. J., & Whitfield, M. M. (2003). Strategy training and working memory task performance. Journal of Memory and Language, 49(4), 446–468.

Unsworth, & Engle. (2007). The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychological Review, 114, 104–132.

Unsworth, N., Heitz, R. P., Schrock, J. C., & Engle, R. W. (2005). An automated version of the operation span task. Behavior Research Methods, 37(3), 498–505.

Unsworth, N., Redick, T. S., Heitz, R. P., Broadway, J. M., & Engle, R. W. (2009). Complex working memory span tasks and higher-order cognition: a latent-variable analysis of the relationship between processing and storage. Memory, 17(6), 635–654.

Van Dam, N. T., van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2017). Mind the hype: a critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13, 1–26.

Wallace, B. A. (1999). The Buddhist tradition of Samatha: methods for refining and examining consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6(2–3), 175–187.

Was, C. A., Rawson, K. A., Bailey, H., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Content-embedded tasks beat complex span for predicting comprehension. Behavior Research Methods, 43(4), 910–915.

Watier, N., & Dubois, M. (2016). The effects of a brief mindfulness exercise on executive attention and recognition memory. Mindfulness, 7(3), 745–753.

Wilhelm, O., Hildebrandt, A. H., & Oberauer, K. (2013). What is working memory capacity, and how can we measure it? Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 433.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. As both of the authors practice mindfulness meditation, a reviewer astutely questioned whether this can be a conflict of interest. There is no gain for the authors other than scientific knowledge.

Appendices

Appendix A: Training overviews provided to mindfulness and cognitive training groups

Mindfulness training (MT) overview

Please read this page every day for the first week of training, as different parts will stand out to you on different days.

You will practice mindfulness training (MT) to cultivate awareness of yourself as well as your environment. MT also teaches you how to regulate your emotional responses to everyday stressful events. You will practice finding a balance between a relaxed state of mind and a highly attentive one. This involves learning to rest your mind in its natural awareness, uncluttered by the distractions of daily life, memories of the past, or concerns about the future.

We are going to be training you, just like you would train your biceps in a gym, to train your mind to attend to the present moment and to control the way it responds to stressors and different emotions. Therefore, MT is a practice that will teach you moment to moment awareness of all the things inside your mind.

Being mindful is something you can do at any point during your day, as many times as you would like. You simply take a deep breath, bring your attention to what is happening in the present moment, and observe what is going on in your mind, your body, and your environment.

You will likely notice that your mind is very busy and will wander off during MT. Mentally noting or becoming aware of how busy your mind can be is one of the most important aspects of MT. What you do is acknowledge when your mind has wandered, let the distraction go, and gently bring your attention back to the MT instructions. You simply start over. Most importantly, you do not judge yourself or get frustrated: you take it easy on yourself. You can start over hundreds to thousands of times. It is part of the training. You are training your mind.

Each time you practice, sit upright in a comfortable position with your back straight and your feet flat on the floor. You may close your eyes or keep them open; whatever feels comfortable to you.

Cognitive training (CT) overview

Please read this page every day for the first week of training, as different parts will stand out to you on different days.

You will practice frequent cognitive training (CT) to develop your abilities across a range of tasks. By engaging in frequent and varied forms of CT, you may be able to improve your cognitive functioning. This may occur not only for the tasks you practice with, but may also transfer to other non-practiced tasks.

We are going to be training you, just like you would train your biceps in a gym, to train your mind to improve on various tasks. Try your best to be fully engaged in each task and complete it to the best of your current abilities. Different tasks will have different goals, such as remembering as many items as possible (i.e. item span tasks) or working with distractions (i.e. executive tasks). Your goal is to keep improving on each task; for example, in the item span tasks this means increasing the number of items you can remember. It is OK if you improve more or faster on some tasks than others, or even if you don’t improve at all on some tasks.

The tasks you will be training on involve skills and abilities you will likely find useful outside of the laboratory. As previously mentioned, your tasks will involve remembering as many items as possible or responding to certain stimuli instead of irrelevant stimuli. In your day to day life, you’ve likely noticed that it is often helpful to remember more things at a given time than less; for example, numbers in a phone number, items in a grocery list, or facts in a lecture. Similarly, it is often helpful to respond only to certain stimuli rather than others; for example, hitting the brakes for a red light rather than the gas pedal, reading your textbook rather than listening to music, or making healthy eating choices instead of ordering fast food.

The abilities you develop during CT may carry over into unpracticed tasks. Work as quickly and as accurately as possible. Do not be discouraged if a task seems difficult or if you don’t improve as much as on other tasks.

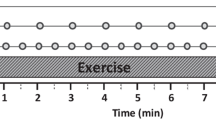

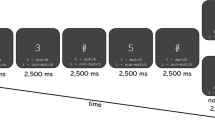

Appendix B: Mindfulness meditation and cognitive training group activities, days 2–9

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baranski, M.F.S., Was, C.A. A More Rigorous Examination of the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Working Memory Capacity. J Cogn Enhanc 2, 225–239 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0064-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0064-5