Abstract

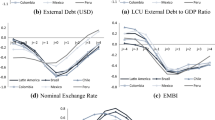

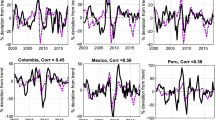

Fluctuations in commodity prices are often associated with macroeconomic volatility. But not all nations are created equal in this regard. The macro response to commodity booms and busts depends both on the structural characteristics of the economy and on the policy framework that is in place. This paper investigates the macro response of a group of commodity-producing nations in episodes of large commodity prices shocks. First, it provides a theoretical framework to analyze how shocks to commodity prices affect the domestic economy. For this the paper uses a simple open-economy model with nominal rigidities and financial frictions. Then it provides empirical evidence (using commodity price boom and bust episodes) that commodity price shocks have a significant impact on output and investment dynamics. Economies with more flexible exchange rate regimes exhibit less pronounced responses of output during these episodes. The paper also provides evidence that the impact of those shocks on investment tends to be larger for economies with less developed financial markets. Moreover, it finds that international reserve accumulation, more stable political systems, and less open capital accounts tend to reduce the real exchange rate appreciation (depreciation) in episodes of commodity price booms (busts).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Current-period variables have no time subscripts. Future-period variables have a 1 as subscript.

This can be derived from utility maximization by workers if their objective function is logarithmic in consumption and C.E.S. in labor effort. See Céspedes, Chang, and Velasco (2004) and Velasco (2001).

The assumption that capitalists consume only foreign goods (in the second period) does not affect qualitatively the results. As it will become clear later, allowing capitalists to consume domestic goods in the second period would affect the market-clearing condition for the second period but it would not alter qualitatively our results.

Notice that we have assumed that all the natural resource endowment belongs to capitalists. Alternatively, a fraction of this endowment may belong to workers or the government (in a model with a government sector). In this case, the impact of terms-of-trade shocks on capitalists’ net worth will feature an additional channel: revenues coming from domestic production associated to higher consumption and government expenditures. Obviously, given differences in preferences over domestic and foreign goods, the quantitative impact may be different depending on who owns the natural resource endowment. For simplicity we shut down this channel.

This is similar to Krugman (1999), and can be justified by positing that the foreign intratemporal elasticity of substitution in consumption is one, but that foreigners’ expenditure share on domestic goods is negligible.

It is given by production function (2), evaluated at the inherited K and L=1 as indicated by Equation (3).

For this to be the case we need β> (1+λ)α, which we assume from now on.

Under the flexible-price equilibrium, output of the domestic good should be equal to the output level under the nonshock equilibrium.

Given that the countries under empirical analysis are mainly middle-income economies, we expect to capture the negative portion of the relationship described.

This last effect requires X>(1+λ)−1(1+ρ)F, meaning that exports of the home good have to be sufficiently high relative to debt service.

The 50-year moving average in each year is computed averaging 40 years back and 10 years ahead. The commodity price trend for the 2000s is assumed to be equal to the commodity price trend for the year 2000.

Nonetheless, the original export-based index is used in the regression analysis.

For the bust episodes we consider the dynamics during the whole episode.

The variables real output, investment, real exchange rate, domestic credit to the private sector, and international reserves come from the WDI. The sources of the remaining variables used in the empirical analysis are described in the main text.

In the exchange rate classification constructed by Ilzetzki, Reinhart, and Rogoff, there are 14 categories: no separate legal tender, preannounced peg or currency board arrangement, preannounced horizontal band that is narrower than or equal to +/−2 percent, de facto peg, preannounced crawling peg, preannounced crawling band that is narrower than or equal to +/−2 percent, de facto crawling peg, de facto crawling band that is narrower than or equal to +/−2 percent, preannounced crawling band that is wider than or equal to +/−2 percent, de facto crawling band that is narrower than or equal to +/−5 percent, moving band that is narrower than or equal to +/−2 percent, managed floating, freely floating and freely falling. In our analysis we ignore the freely falling category in a similar way than Aghion and others (2009). In one extreme, a no separate legal tender regime takes a value of 1 while in the other extreme a freely floating regime takes a value of 13.

The rule of law index is constructed by the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). It ranges from 0 to 6, where a higher number is associated with stronger law and order tradition.

We use for this computation the average for the statistically significant coefficients computed in Table 3 for the response of changes in the output gap to changes in the commodity price index during the episode.

A freely floating regime takes a value of 13 while a de facto peg regime takes a value of 3. We use for this computation the average for the statistically significant coefficients computed in Table 3 for the response of changes in the output gap to the exchange rate flexibility variable.

The results obtained using the production-based commodity price index are similar to the ones obtained using the export-based commodity price index. They are presented in the last panel of Table 7.

Table 7 Macroeconomic Dynamics in Commodity Price Boom and Bust Episodes

References

Adler, G., and C. Tovar, 2011, “Foreign Exchange Intervention: A Shield Against Appreciation Winds?” IMF Working Paper 11/165 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Aghion, P., P. Bacchetta, R. Rancière, and K. Rogoff, 2009, “Exchange Rate Volatility and Productivity Growth: The Role of Financial Development,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 56, No. 4, pp. 494–513.

Aizenman, Joshua, Sebastian Edwards, and Daniel Riera-Crichton, 2011, “Adjustment Patterns to Commodity Terms of Trade Shocks: The Role of Exchange Rate and International Reserves policies,” NBER Working Papers 17692 (National Bureau of Economic Research).

Broda, Christian, 2004, “Terms of Trade and Exchange Rate Regimes in Developing Countries,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 31–58.

Cashin, Paul, Luis F Cespedes, and Ratna Sahay, 2004, “Commodity Currencies and the Real Exchange Rate,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 75, No. 1, pp. 239–268.

Céspedes, L., R. Chang, and A. Velasco, 2003, “IS-LM-BP in the Pampas,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 50, No. Special Issue, pp. 143–156.

Céspedes, L., R. Chang, and A. Velasco, 2004, “Balance Sheets and Exchange Rate Policy,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 4, pp. 1183–1193.

Céspedes, Luis F., and Andres Velasco, 2011, “Was This Time Different?: Fiscal Policy in Commodity Republics,” BIS Working Papers 365 (Bank for International Settlements).

Chen, Y., and K. S. Rogoff, 2003, “Commodity Currencies,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 60, No. 1, pp. 133–160.

Chinn, Menzie D., and Hiro Ito, 2008, “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 309–322.

Deaton, Angus, and Ronald Miller, 1996, “International Commodity Prices, Macroeconomic Performance, and Politics in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of African Economies, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 99–191.

De Gregorio, J., and F. Labbé, 2011, “Copper, the Real Exchange Rate and Macroeconomic Fluctuations in Chile,” in Beyond the Curse: Policies to Harness the Power of Natural Resources, ed. by. Arezki R., T. Gylfason and A. Sy (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Edwards, Sebastian, and Eduardo Levy Yeyati, 2005, “Flexible Exchange Rates as Shock Absorbers,” European Economic Review, Vol. 49, No. 8, pp. 2079–2105.

Frankel, J., 2010, “A Comparison of Monetary Policy Anchor Options, Including Product Price Targeting, for Commodity-Exporters in Latin America,” NBER Working Paper No. 16362.

Ilzetzki, E., C.M. Reinhart, and K.S. Rogoff, 2008, “Exchange Rate Arrangements Entering the 21st Century: Which Anchor Will Hold?” mimeo.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2012, World Economic Outlook, World Economic and Financial Surveys (Washington, April).

Kearns, Jonathan, and Roberto Rigobon, 2005, “Identifying the Efficacy of Central Bank Interventions: Evidence from Australia and Japan,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 31–48.

Kose, M.Ayhan, 2002, “Explaining Business Cycles in Small Open Economies ‘How Much do World Prices Matter?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 299–327.

Krugman, P., 1999, “Balance Sheets, The Transfer Problem, and Financial Crises,” in International Finance and Financial Crises: Essays in Honor of Robert Flood, ed. by Isard P., Razin A., Rose A. (Dordrecht, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers-IMF).

La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny, 1997, “The Legal Determinants of External Finance,” The Journal of Finance, Vol. LII, No. 3, pp 1131–1150.

Mendoza, E.G., 1995, “The Terms of Trade, the Real Exchange Rate, and Economic Fluctuations,” International Economic Review, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 101–137.

Ricci, L.A., G.M. Milesi-Ferretti, and J. Lee, 2008, “Real Exchange Rates and Fundamentals: A Cross-Country Perspective,” IMF Working Paper 08/13 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Spatafora, Nikola, and Irina Tytell, 2009, “Commodity Terms of Trade: The History of Booms and Busts,” IMF Working Paper 09/205 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Velasco, Andrés, 2001, “The Impossible Duo? Globalization and Monetary Independence in Emerging Markets,” Brookings Trade Forum, Vol. 2001, No. 1, pp. 69–111.

Additional information

Prepared for the IMF-CBRT “Policy Responses to Commodity Price Movements” Conference—April 6–7, 2012.

*Luis Felipe Céspedes is an Associate Professor of Economics in the Business School at Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez. Andrés Velasco is Visiting Professor in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and a Research Associate at the NBER. The authors are grateful to Juan Matamala for excellent research assistantship. They are also grateful to Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and Ayhan Kose (the editors), two anonymous referees, and our discussant Silvana Tenreyro for useful comments and suggestions. The authors thank Gustavo Adler, Cesar Calderon, Luis Catao, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, and Nikola Spatafora for sharing their data with them.