Abstract

Managed care provides health insurers a unique opportunity for discretion over certain aspects of financial reporting. Specifically, managed care mechanisms provide health insurers with a stronger ability to engage in loss control. To test whether and how health insurers exploit their ability to manage losses, we examine whether insurers with greater opportunity to manage care report significantly better underwriting performance in the fourth quarter relative to other health insurers. Using quarterly statutory filings from 2003 to 2016, we find evidence that a health insurer’s share of enrollment in health maintenance organisation (HMO) plans, characterised by their use of ‘gatekeeper’ physicians, is significantly and negatively related to their reported fourth quarter medical loss ratio (MLR). Additionally, while we find that fourth quarter MLRs are higher for all health insurers following the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), the ACA does not appear to have intensified the loss control efforts of those insurers with more enrollment in HMO plans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Managed care health insurance plans were designed to achieve three interrelated objectives: to curb rising healthcare costs, to control utilisation and to improve the quality of healthcare services (Schield et al. 2001). Health insurers meet these objectives through a combination of mechanisms that include traditional cost-sharing provisions such as deductibles and copayments, contracting with healthcare providers, methods of payment to those providers such as capitation, and mechanisms for monitoring health insurance enrollee utilisation of healthcare services (Glied 2000). While insurers use managed care techniques to varying degrees across different types of plans, the most unique mechanism is the use of a ‘gatekeeper’ healthcare provider, which is used primarily by health maintenance organisation (HMO) plans. A gatekeeper mechanism requires enrollees to visit a primary care provider, who is tasked with preventive care and acts as the gateway for enrollees to access a specialist for care. HMO gatekeepers regulate the enrollee’s access to and use of healthcare services, thus providing the insurer that administers the HMO plan with an important loss control service.Footnote 1

When an insurance contract is established between insurers and insureds, insurers generally have few opportunities to mitigate losses. An auto insurer cannot, for example, require that an auto insurance customer change her driving habits in the middle of the policy year. Health insurers that offer HMO plans, on the other hand, can apply managed care mechanisms, such as evaluating the necessity, appropriateness, and efficiency of healthcare services, to varying degrees over the policy period, allowing them a unique opportunity, relative to insurers that offer other types of health insurance plans, to actively engage in loss control. The ability to directly manage the provision of healthcare services through the gatekeeper provider gives HMO insurers an additional tool for manipulating financial reporting throughout the year as insurers are required to report aggregate premium and claims (i.e. losses) information.

In this paper, we evaluate variation in health insurer underwriting profitability from 2003 to 2016 using data from quarterly and annual statutory statements. Quarterly data allow us to recognise two unique aspects of health insurance: (1) given that health insurance policies are written on a calendar-year basis, we are able to clearly observe the development of underwriting profitability over the course of the year, and (2) the proportion of health insurance enrollees who have met the annual deductible increases throughout the calendar year which could increase enrollee demand for services toward the end of the policy year (i.e. moral hazard).Footnote 2 While U.S. health insurers offer a host of managed care plans, insurers reporting to state regulators are required to report enrollment in one of six types of plans, including HMOs. Along with the gatekeeper requirement, HMOs also restrict enrollees from accessing any providers outside of the insurer’s network. There is no insurance coverage in an HMO for services rendered ‘out-of-network’. Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plans allow enrollees to access specialist services without a gatekeeper and, unlike in HMO plans, enrollees in PPO plans can access out-of-network providers and still receive some coverage from the plan albeit at a higher out-of-pocket cost. PPO plans counteract the restrictive nature of HMO plans. Thus, on a spectrum of managed care intensity, the liberal nature of PPOs places them closer to the traditional indemnity plans, which have been declining in popularity.Footnote 3 HMO plans are the most restrictive type of managed care plan in terms of managed care intensity. In our spectrum of plans, we consider traditional indemnity and PPO plans to be on the liberal end of the spectrum, HMO plans on the conservative side, and Point of Service (POS) plans somewhere in the middle.Footnote 4

Using ordinary least squares (OLS) and quantile regressions, we regress fourth quarter underwriting performance, defined as the medical loss ratio (MLR) on the percentage of an insurer’s enrollment that is in HMOs—which proxies for higher levels of managed care—relative to other types of managed care plans that do not use the gatekeeper mechanism as we are interested in the relation between managed care and fourth quarter underwriting results. While almost all other health insurance plans offered in the U.S. today represent some form of managed care, a visit to a gatekeeper is not generally a requirement for accessing medical services. Thus, HMOs have access to a loss control mechanism that is not available to all other health plans. We also evaluate whether quarterly underwriting performance changed following enactment of key legislation within the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

We provide robust evidence that health insurers with a higher percentage of enrollment in HMOs report significantly lower MLRs in the fourth quarter, suggesting that health insurers with more intense managed care operations (i.e. higher percentage of enrollment in HMO plans) use their managed care mechanisms to improve their financial reporting. Specifically, our results suggest that an insurer with 100% enrollment in HMO plans will have a fourth quarter MLR that is 3% to 9% lower relative to an insurer offering plans with no HMO enrollment. Additionally, we find evidence that this relationship between managed care intensity and fourth quarter underwriting results remains consistent through our sample. Although we find that the post-ACA period is associated with higher MLRs, generally, indicating overall worse performance for all insurers, the regulatory changes introduced with the passage of the ACA did not further incentivise managed care-intensive health insurers (i.e. those insurers with higher percentages of enrollment in HMO plans) to manage fourth quarter reporting. Overall, our results provide evidence that the managed care function may add value to insurers’ ability to smooth underwriting and, therefore, overall performance.

We make several contributions to the literature. First, we contribute to the large body of literature evaluating the function of managed care and the market implications associated with health insurance plans that incorporate loss control. The literature is replete with comparisons of HMOs with fee-for-service (i.e. indemnity) plans that examine demand-side outcomes such as the impact of managed care on quality of care (e.g. Miller and Luft 1997; Hellinger 1998; Scanlon and Chernew 2000), patient satisfaction (e.g. Miller and Luft 1994; Simonet 2005), and patient provider relationships (e.g. Mechanic and Schlesinger 1996; Hall et al. 2002). Explicit evaluations of the financial performance of managed care plans include those that evaluate the role of health insurer profit status (e.g. Bryce 1994; Born and Simon 2001) and the impact of mergers and acquisitions (Weech-Maldonado 2002). We extend this literature by focusing on the additional benefit of loss control inherent in HMO plans that can employ managed care mechanisms—specifically the gatekeeper mechanism—with varying intensity.

We also contribute to the accounting literature by evaluating earnings management within the health insurance context. While there is a rich academic area examining accounting discretion in both the non-health insurance industry (e.g. Petroni 1992; Nelson 2000; Grace and Leverty 2010; Berry-Stölzle et al. 2018) as well as the hospital industry (e.g. Leone and Van Horn 2005; Eldenburg et al. 2011; Vansant 2016), relatively fewer studies examine health insurer accounting practices (e.g. Belina et al. 2019). We are the first, to our knowledge, to link managed care intensity to underwriting profitability in the fourth quarter.

Finally, we contribute to the growing body of literature around the consequences of the ACA. While several studies have examined how ACA provisions have affected insurance demand and issues related to health and market outcomes (e.g. Baicker et al. 2013; Barbaresco et al. 2015; Sommers et al. 2015; Born and Sirmans 2020), our focus is on the supply-side results of imposing new regulations in this industry. While we do not infer a causal connection between the ACA and quarterly management of losses, we provide a review of ACA provisions that may have influenced the opportunities or incentives for health insurers to more closely manage losses through the gatekeeper function in the fourth quarter. We therefore specifically contribute to the literature examining the impact of the ACA on health insurers (e.g. Cicala et al. 2019; Callaghan et al. 2020; Eastman et al. 2021).

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we provide background on managed care, accounting discretion and the ACA. The third section presents our testable hypotheses. In the fourth section, we present our empirical approach. We summarise the results in section five and a final section concludes.

Background

Our analysis of health insurer profitability draws on three areas of the literature: managed care, accounting discretion, and the ACA.

Managed care

Health insurance has evolved over the last century from a marketplace where pre-paid hospital and physician care plans were sold alongside indemnity plans to a heavily-subsidised market dominated by employer- and government-sponsored managed care plans with nearly seventy percent of all healthcare expenditures paid through a private health insurer or government health insurance programme.Footnote 5 The precipitous growth of managed care plans through the 1980s transformed the landscape in which health insurers operated.Footnote 6 Indeed, managed care plans are now ubiquitous in the U.S. market and few plans exist that resemble indemnity or fee-for-service (Kaiser Family Foundation 2019).

Health insurers offer coverage through a variety of managed care plan arrangements with varying degrees of control over medical resource enrollee use. HMO plans exercise the most aggressive use of managed care given that gatekeepers are used for utilisation review to control enrollees’ access to specialists and specialty services. PPO and POS plans, on the other hand, are considered less managed since there is no requirement to obtain approval for specialist services from a gatekeeper and services rendered ‘out-of-network’ are still eligible for payment. All insurers offering managed care plans have the option to exercise utilisation review aggressively to varying degrees throughout the year, but we assume that only in the HMO plan does an insurer have decisive control over losses in the fourth quarter.Footnote 7 Through more aggressive application of utilisation review (e.g. denying or delaying diagnostic tests or procedures) the HMO plans can manipulate the fourth quarter performance, as needed, in a way other plans cannot.

The academic literature on managed care primarily reflects a demand-side perspective, evaluating issues within managed care companies such as patient access to services and quality of care (Miller and Luft 1997; Brockett et al. 2021), patient satisfaction (Miller and Luft 1994, 2002), or the implications of the payment arrangements between providers and health insurers such as capitation (Grumbach et al. 1998).Footnote 8 The extent to which managed care techniques are used by health insurers has received less attention, particularly as it pertains to the stated purpose of controlling costs. Comparisons of HMOs and PPOs, for example, note that the differential restrictions on the enrollee’s choice of provider in these types of plans might explain selection bias in these plans (Hellinger 1995) and the widening appeal of less-restrictive PPOs (Hurley et al. 2004). However, the extent to which HMOs, PPOs or health insurers administering managed care plans more generally, make use of particular managed care techniques is not well addressed by the existing literature.Footnote 9

The literature includes a wide range of studies addressing various legal consequences of managed care. Since its inception, managed care has flirted with various financial incentive arrangements for providers to limit services which has, consequently, fueled a long-running discussion of how to assign liability for bad faith actions (Hall 1988, 1989; Schessler 1992; Havighurst 2000; Arlen and MacLeod 2005). Despite the potential legal liability that may arise from coverage decisions, utilisation review provides one straightforward tool for managing the allocation of premium revenue to claims, thereby managing earnings, especially as it can—at least theoretically—be applied by providers with varying degrees of aggressiveness as needed throughout the contract period. The current literature has not explored this possibility, to our knowledge.

The evaluations most closely related to our study of health insurer financial performance largely involve comparisons of managed care plans based on profit status (Bryce 1994; Born and Simon 2001). Prior research has also linked financial performance to the quality of care (Born and Geckler 1998) which was studied in detail as the industry consolidated through the 1990s, with a focus on the outcomes of mergers and other changes to the health insurance market structure (Pauly 1998). Other studies have considered the response of health insurer stock prices to changes in regulation (Jacobson 1994; Strange and Ezzell 2000). While these studies generally recognise the differentiation of HMOs, PPOs and other forms of managed care, we are not aware of any that explicitly consider how financial performance relates to the extent to which health insurers have enrollment in different types of managed care plans.

Accounting discretion

Earnings management, broadly defined, refers to managers using their discretion over financial reporting “to either mislead some stakeholders about the underlying economic performance of the company, or to influence contractual outcomes that depend on reported accounting numbers” (Healy and Wahlen 1999, p. 368). While there is a broad literature examining all aspects of earnings management (see Dechow et al. (2010) for a literature review), our focus is on the subset of earnings management studies which examine whether firms actively manage earnings on a quarterly basis. Foster (1977) derives initial firm-level models of quarterly earnings and finds two components of quarterly accounting data: an adjacent quarter-to-quarter component and a seasonal component. Jacob and Jorgensen (2007) posit that firms are generally more interested in fiscal year (annual) reports. Because managers are not evaluated on a quarterly target, there is less incentive for quarterly management other than a focus on the fourth quarter. In contrast, Degeorge et al. (1999) find evidence that firms manage quarterly earnings to achieve thresholds. Dhaliwal et al. (2004) find evidence that firms use ‘last chance earnings management’ (i.e. fourth quarter), through the tax expense, to beat analyst forecasts.

An additional strand of the earnings management literature examines whether firms use real earnings management in response to various incentives (e.g. Roychowdhury 2006; Cohen and Zarowin 2010; Eldenburg et al. 2011). Examples of real earnings management include offering price discounts to temporarily increase sales or decreasing discretionary expenditures, such as research and development expenditures. Compared to accrual-based earnings management—which will eventually ‘unwind’ and, therefore, only has a temporary effect—real earnings management can have permanent implications for investors. Real earnings management is relevant to our setting as certain aspects of managed care could have real implications for financial statements (as well as policyholders).

While there are relatively few studies specifically examining health insurer accounting practices, there are two main streams of literature that are adjacent to health insurer earnings management. The first area examines earnings management in the broader healthcare industry, including examining issues such as earnings management within hospitals (Leone and Van Horn 2005; Eldenberg et al. 2011; Boterenbrood 2014) and the impact of regulation on real activities (Mittelstaedt et al. 1995), and on capital expenditures and cost-effective behaviour (Barniv et al. 2000) within healthcare.Footnote 10 Beneish (2001), in his review and perspective on earnings management, emphasises the need for examining which components of revenues and expenses are discretionary within the healthcare industry, as the bounds for discretion may be different from those in other lines of insurance. The second stream of literature examines accounting practices among non-health insurers. The majority of this literature focuses on loss reserving discretion among property-casualty insurers, finding that insurers use discretion over their loss reserves to avoid solvency regulation (Petroni 1992), to smooth earnings (Beaver et al. 2003), and in response to stringent rate regulation (Nelson 2000; Grace and Leverty 2010).

The three closest studies to ours are Mensah et al. (1994), Cicala et al. (2019) and Eastman et al. (2021). Mensah et al. (1994) find evidence that financially weak managed care plans (specifically, HMOs) systematically understate incurred but not reported (IBNR) claims. Cicala et al. (2019) find that the MLR requirements imposed by ACA legislation incentivised insurers to increase costs. Claims rose nearly one-for-one with distance below the required minimum while premiums were unaffected. Eastman et al. (2021) empirically examine whether health insurers inflate their loss estimates in an attempt to pay lower rebates in response to the ACA’s minimum MLR standards. They find evidence that consumer rebates would be 10% higher if insurers perfectly forecasted losses. Unlike the studies noted above, our study examines the potential for the managed care function to increase opportunities for accounting discretion.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The ACA represented substantial healthcare reform with direct implications for health insurer operations (Harrington 2010). Below, we discuss specific provisions of the ACA which had the potential to not only transform the scope of the insurance industry as a whole but also impose incentives for health insurers to manage losses (i.e. claims) through utilisation review.

Three key provisions encouraged substantial increases in health insurance enrollment which, in turn, may have incentivised health insurers to control losses simply due to a greater number of applicants for coverage and the uncertainty of the risk-level of enrollees: the individual mandate, expansion of the Medicaid programme to include coverage for working, childless adults up to a certain percentage of the Federal Poverty Level, and the implementation of state-level online exchanges for the individual and small group markets. The individual mandate for coverage requires proof of health insurance coverage during the year.Footnote 11 This mandate was a partial means to mitigate adverse selection in the market by potentially inducing low-risk enrollees to take up health insurance coverage (NAIC 2011). Medicaid expansion broadens coverage under the Medicaid programme to include health insurance for low-income, non-disabled adults provided the state chose to adopt the Medicaid expansion provision. Medicaid expansion may impact health insurer operations given that the majority of states rely on the private market to provide coverage for Medicaid enrollees and those Medicaid managed care organisations bear the risk for those enrollees (Rudowitz et al. 2018).Footnote 12 The individual/small group market exchanges, mandated by the ACA, have the potential to alter health insurer operations by standardising coverage and creating economies of scale where health insurers can participate in the individual market with fewer barriers to entry and potentially reduced administrative costs.Footnote 13,Footnote 14

Mandated adjusted community rating and the prohibition on medical underwriting has the potential to incentivise health insurers to control losses because, theoretically, in a rating environment that lacks risk classification, insurers may experience higher-than-expected losses.Footnote 15 While the resulting adverse selection may not impact the entire market at the extensive margin, when coverage is nearly universal, it has the potential to impact the intensive margin of adverse selection against particular plans (Buchmueller and DiNardo 2002).Footnote 16 Additionally, because coverage is guaranteed under the ACA, insurers do not have sufficient means to deny coverage at the extensive margin and so the incentive may be increased for closer management of earned premiums and losses once the contracts are in place.

Finally, minimum MLR requirements post-ACA dictate that a certain percentage of premiums be spent on claims and other allowable expenses in specific markets for health insurance lest rebates be paid to policyholders. This provision is of particular interest to our study as there is evidence that health insurers systematically overstate claims estimates following the ACA (Eastman et al. 2021) and insurers manage MLRs toward the standard requirement in the post-ACA period (Callaghan et al. 2020).Footnote 17,Footnote 18

Overall, health insurer usage of the managed care function, namely the use of gatekeeper providers in managing fourth quarter performance, remains an empirical question. As noted above, health insurers have varying incentives and opportunities to manage fourth quarter performance using the unique aspect of HMOs, which requires enrollees to access care through a gatekeeper. Additionally, given that our data span a time during which health insurance markets saw substantial reform, the impact of the ACA on health insurer operations remains an empirical question as well. Research on health insurer response to the legislation and/or health insurer performance following the reform is sparse. However, given the changes to the health insurer risk-bearing environment noted above, incentives for managing fourth quarter performance may be increased.

Hypotheses development

Health insurer performance, particularly across quarters, has largely not been investigated in the literature. The function of managed care is designed to address an agency problem. Containment of healthcare costs is nearly impossible in the traditional indemnity coverage environment, as healthcare providers who are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis have little incentive to control utilisation of these services. The unique feature of managed care plans, generally, is that loss control is integrated with the insurance product by design. As noted above, health insurers operate on a calendar-year basis allowing us to evaluate performance between and across quarters. Management of care and, consequently, management of losses (i.e. claims) can occur throughout the calendar year, but the fourth quarter is the insurer’s last opportunity to control annual experience.Footnote 19 Additionally, health insurers may face higher demand for services in the fourth quarter from enrollees who have met an annual deductible and therefore may have increased incentives to utilise coverage.Footnote 20 Thus, there may be incentives to smooth income annually by focusing on the fourth quarter in particular. Additionally, as noted above, health insurers operating with more enrollment in HMO plans, relative to other types of managed care plans, may have greater opportunity to manage losses due to the gatekeeper function inherent in the HMO plan relative to the plans that do not have the gatekeeper restriction. Therefore, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1

Fourth quarter MLRs are lower for health insurers that have a greater share of HMO enrollment.

Further, as discussed previously, several ACA provisions had the potential to transform the environment in which health insurers operate. Provisions to increase enrollment may have incentivised management of fourth quarter performance by changing the risk characteristics of the population insured, exacerbating adverse selection through rating restrictions, or inducing management of accounting information. While we do not formally test each provision of the ACA, we hypothesise that the provisions generally hinder insurers’ ability to manage performance, which may materialise more profoundly in the fourth quarter experience. To an extent, then, the provisions may have incentivised health insurers to further manage performance, perhaps employing greater use of managed care techniques such as utilisation review. Insurers with greater opportunities to manage performance (i.e. those with a higher percentage of enrollment in HMO plans) might exhibit additional earnings management in the fourth quarter when compared to health insurers with fewer opportunities. Thus, we propose,

H2

Fourth quarter MLRs in the post-ACA period are higher than in the pre-ACA period.

H3

Compared to pre-ACA fourth quarter MLRs, fourth quarter MLRs post-ACA are lower for health insurers that have a greater share of HMO enrollment.

Ultimately, we expect to find a relationship between fourth quarter MLRs and a greater percentage of business in HMO plans. We expect fourth quarter MLRs of all insurers to be higher in the post-ACA period, but that health insurers with more enrollment in HMOs have significantly lower fourth quarter MLRs.

Research design

Data and sample selection

Our initial dataset consists of all health insurers that file quarterly and annual statutory statements to state regulators. Those statements are then compiled by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) for the years 2003 to 2016, the database from which we draw the data for our study. We primarily draw from two health insurer exhibits: (1) the Exhibit of Premiums, Enrollment, and Utilization, which is reported quarterly and annually. The data include health premiums earned, amount incurred for provision of healthcare services (i.e. losses or claims), member months and utilisation. (2) The Exhibit 1—Enrollment by Product Type for Health Business Only, which lists member months by product type (e.g. HMO, PPO, POS or indemnity). We supplement this data with information on insurer characteristics such as ownership structure and insurer size taken from the annual health insurer statutory filing. We exclude observations where the insurer primarily operated in dental and vision (percent of premiums written in dental plus vision is greater than 50% of total premiums). We additionally exclude observations where premium and loss information is not available for all four quarters in a given year. All continuous variables are winsorised at the 1 and 99 percent levels. Our final sample consists of 4278 insurer-year observations representing 685 unique health insurers.

Our main variable of interest is the quarterly MLR, defined as the quarterly provision of healthcare services (i.e. claims or losses) divided by quarterly premiums earned. Since our main analysis is at the insurer-year level, each insurer-year observation has a separate MLR for each quarter (labeled MLR Q1, MLR Q2, MLR Q3, and MLR Q4). Our key control variable, HMO Percent, is the percentage of HMO member months relative to total member months.Footnote 21,Footnote 22

We additionally include a vector of insurer-level control variables commonly associated with insurer performance to isolate the relationship between managed care and fourth quarter MLRs. While the variation in underwriting performance due to differential insurer characteristics is likely captured in each of the quarterly MLRs, inclusion of insurer controls assures that we are isolating the effect of managed care activities in the fourth quarter from these drivers. For example, we control for insurer size (ln(Assets)) to account for economies of scale that arise from increased potential bargaining power among larger insurers (e.g. Dafny 2010). Larger insurers typically report more favorable underwriting performance. Hence, we expect size to be negatively related to an insurer’s MLR, generally, all else equal. We control for an insurer’s capital structure (Premiums-to-Surplus) to control for their capacity to bear risk (Winter 1994). Empirical studies generally include this ratio in analyses of underwriting performance in the property and casualty industry but provide mixed evidence of a relationship (Higgins and Thistle 2000). We suspect that underwriting leverage may play into fourth quarter decisions for health insurers, particularly those with business in product lines that are constrained by ACA minimum loss ratio requirements, such that fourth quarter MLRs may be higher for insurers with higher premiums-to-surplus ratios. Indicators for ownership structure (i.e. binary variables, Public and Mutual) control for potential differences in agency costs and monitoring ability in different organisational forms (Mayers et al. 1981).We propose that a public or mutual insurer may be less likely to institute adjustments to utilisation review protocols than a stock company that must satisfy shareholders’ dividend expectations.Footnote 23 Finally, we control for changes in the interest rate environment that may influence rate calculations by including T-Bill. We report variable definitions in Table 1.

Determinants of fourth quarter MLRs

To test our hypothesis of whether the MLR Q4 is related to managed care intensity (i.e. HMO Percent), we estimate the following model for the entire sample period using OLS:

where MLR Q4i,t is insurer i’s fourth quarter MLR (defined as the fourth quarter provision of healthcare services (i.e. claims or losses) incurred to fourth quarter premiums earned) in year t. HMO Percenti,t is insurer i’s member months in HMO plans divided by total member months in year t.Footnote 24Xi,t is a vector of insurer-level control variables. It and Ii are year and insurer fixed effects, respectively. \(\epsilon_{i,t}\) is a random error term. Standard errors account for insurer-level clustering. Positive coefficient estimates represent a higher fourth quarter MLR while negative coefficients represent a lower fourth quarter MLR. Therefore, a negative and statistically significant coefficient estimate for HMO Percenti,t (β < 0) would be consistent with our hypothesis that the percentage of HMO enrollment can lead to better fourth quarter performance, as measured by MLRs.

In addition to estimating the model using OLS (with and without insurer fixed effects) we estimate the model using quantile regressions.Footnote 25 In our final analysis, we use OLS again to estimate the model presented in Eq. (1) with controls to test whether our empirical findings are affected by implementation of key provisions of the ACA. We define a variable ACA which is one if the year is 2011 or later since 2010 is the year the ACA was signed into law.

Results

Descriptive statistics

We present summary statistics for our sample in Table 2. Just over 69% of member months in our sample are in HMOs. The median insurer-year in our sample, however, has over 99% of member months in HMOs. The average quarterly MLRs are all relatively similar across the four quarters, though the average fourth quarter MLR is the highest at 86.58.

We provide univariate differences based on managed care status for our quarterly MLRs in Table 3. In this analysis we define all insurer-years in our sample as either an HMO insurer or a non-HMO insurer based on the most prevalent enrollment type (i.e. if an insurer has more member months in HMO than PPO or POS they are defined as an HMO insurer, while all others are defined as non-HMOs). In column (1), examining only HMO insurers, we observe that the fourth quarter MLR is not statistically significantly different from the first or second quarters, but is statistically significantly higher than the third quarter MLR. While this runs counter to our expectation, this univariate analysis does not account for other potentially correlated, but omitted, variables that we will account for in our multivariate tests.

When we examine differences between HMO insurers and non-HMO insurers in Table 3, we observe that fourth quarter MLRs are statistically significantly lower for HMO insurers. This result is consistent with our hypothesis that managed care insurers—specifically those with a greater percentage of enrollment in HMO plans—have a greater ability to manage care in the fourth quarter in an effort to improve performance in financial reporting. We additionally observe that first quarter MLRs are statistically significantly higher for HMO insurers relative to non-HMO insurers. One potential explanation for this result is that HMO insurers are forced to ‘undo’ any care management they perform in the fourth quarter when the new year begins in quarter one (e.g. all delayed appointments are scheduled in the first quarter instead of the fourth quarter), which is reflected in relatively worse first quarter performance. The pattern of MLRs across the four quarters differentiates these two types of insurers; the annual MLRs are not significantly different.

Table 4 provides univariate differences for all variables used in our study in the pre- and post-ACA periods. The mean of HMO Percent does not differ statistically in the pre- and post-ACA periods. While the mean and median differences for first quarter MLRs do not differ significantly, the remaining three quarters do differ across the pre- and post-ACA periods. Specifically, we observe that second, third and fourth quarter MLRs were significantly lower at the mean and median in the pre-ACA period, indicating overall worse performance for all health insurers post-ACA.

Determinants of 4th quarter MLRs

We present results of our empirical estimation of Eq. (1) in Table 5. The dependent variable is MLR Q4. Columns (1) and (2) include year fixed effects while column (2) also includes insurer fixed effects. Each coefficient estimate is presented along with standard errors in parentheses underneath. The standard errors are clustered at the insurer level. Positive coefficient estimates indicate higher fourth quarter MLRs (i.e. worse performance) while negative coefficients indicate lower fourth quarter MLRs (i.e. better performance).

Overall, the results in Table 5 are consistent with our hypothesis. Specifically, the coefficient estimate on HMO Percent is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level in both specifications. This result is consistent with our hypothesis that more managed care intensive insurers experience lower fourth quarter MLRs. Our finding is economically significant in addition to achieving statistical significance—the influence on fourth quarter MLRs of going from no HMO enrollment to all HMO enrollment without insurer fixed effects is equal to an increase of 3.17 points while the influence with insurer fixed effects is an increase of 9.14 points.

For robustness, and because MLR distributions are often skewed, we estimate Eq. (1) again using quantile regression methodology. We present these results in Table 6. Column (1) presents our OLS model (identical to column (1) of Table 5) for ease of comparison. Columns (2) through (6) present results at different quantiles (0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75 and 0.90). All models include year fixed effects.Footnote 26,Footnote 27

The results in Table 6 are consistent with our first hypothesis that insurers with a greater proportion of managed care intensive enrollment (as measured by HMO Percent) tend to have lower fourth quarter MLRs. The coefficient estimate for HMO Percent is negative and statistically significant in all five quantiles. Also, the coefficients are all relatively close in magnitude, ranging from − 0.0178 to − 0.0375. This suggests that the behaviour we observe in our OLS model is not driven by behaviour at any particular part of the distribution (e.g. insurers with the highest fourth quarter MLRs)—the effect appears across the entire distribution of MLRs and managed care.

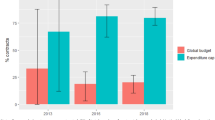

To provide further evidence that this effect occurs across the entire distribution, we present Fig. 1. In addition to the five quantiles in Table 5, we estimate quantile regressions of Eq. (1) at all quantiles from 0.05 to 0.95. We take the estimated coefficient of HMO Percent in each of these models (as well as the 95% confidence interval) and plot them in Fig. 1. We also provide the coefficient estimate and confidence interval for HMO Percent from OLS regression (column (1) of Table 5). Overall, Fig. 1 indicates that while the quantile estimates are closer to zero relative to OLS estimates, the quantile coefficients for HMO Percent are nearly always negative and statistically significantly different from zero (the 95% confidence interval only goes below zero at the low quantiles. Combined with the results in Table 5, Fig. 1 provides evidence that insurers with managed care have better underwriting results (lower MLRs) in the fourth quarter relative to insurers with lower levels of managed care.

This figure reports coefficients on HMO Percent from quantile regressions on the determinants of fourth quarter MLRs (MLR Q4). MLRs are defined as losses incurred divided by premiums earned. The solid gray line is the coefficient estimate of HMO Percent from OLS regressions and the dotted gray lines are the 95% confidence intervals from the OLS regression. The solid blue line represents the coefficient estimate of HMO Percent for quantiles from 5 to 95. The dashed red lines represent the 95% confidence interval around each coefficient estimate

Finally, in Table 7 we examine whether the implementation of the ACA has influenced fourth quarter reporting for health insurers and consider whether the ACA had a differential impact on more managed care-intensive insurers. We evaluate this potential impact in two separate ways. First, we construct a binary variable, ACA, that is equal to one during the ACA period and zero otherwise.Footnote 28 Second, we construct a variable, ACA Trend, that begins counting at the implementation of the ACA and adds one each year.Footnote 29 We then examine separate models on the determinants of fourth quarter MLRs with all prior controls, as well as ACA and ACA Trend on their own, and interacted with HMO Percent.

Table 7 presents our results examining how the ACA influences the behaviour we had previously documented across the entire sample period. We define the ACA period as 2011 and later. First, we observe that the estimated coefficients on HMO Percent are negative and statistically significant in all four specifications. This suggests that controlling for the ACA does not eliminate our previously documented statistical relationship between managed care and fourth quarter MLRs. Additionally, we note that the coefficient estimates for our ACA control variables (ACA and ACA Trend) are positive and statistically significant in all four specifications. These estimates suggest that the ACA resulted in higher fourth quarter MLRs for all insurers in our sample, consistent with higher losses relative to premiums following the passage of the new regulation. Finally, we note that the coefficient estimates on the interaction between managed care and the ACA (HMO Percent*ACA and HMO Percent*ACA Trend) are not statistically significantly different from zero in any of the four models. Taken together, these results suggest that while insurers with a higher percentage of enrollment in HMO plans are able to achieve significantly lower fourth quarter MLRs relative to their peer insurers with a lower percentage of enrollment in HMO plans, and while the ACA resulted in higher fourth quarter MLRs for all insurers relative to the pre-ACA period, the ACA does not differentially impact insurers with a higher percentage of enrollment in HMO plans relative to other insurers: insurers with a higher percentage of HMO plan enrollment, therefore, are performing the same degree of fourth quarter management in the ACA period as they had been previously. In other words, the ACA does not seem to have strengthened or mitigated the ability of insurers to exploit the higher HMO plan enrollment to manage fourth quarter reporting.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examine quarterly underwriting performance across health insurers with differing opportunities for managing enrollee utilisation of the health insurance plan. Our analysis of a large sample of U.S. health insurers over the period 2003–2016 indicates that, controlling for the performance in the first three quarters, managed care intensity—measured by the percentage of enrollment in HMO plans—is negatively related to fourth quarter MLRs. Our finding is economically significant—the estimated influence on fourth quarter MLRs of going from no HMO enrollment to all HMO enrollment ranges from 3.17 to 9.1 points.

Our results provide evidence that the gatekeeper function may add value to insurers’ ability to smooth underwriting and, therefore, overall performance. We expect demand for services in the fourth quarter to increase due to the higher proportion of enrollees who have met their calendar-year deductible, but we find the opposite to be true as managed care intensity—a larger share of enrollees subject to gatekeepers—increases. This suggests that managed care intensive insurers employ the opportunity to manage the provision of healthcare services more aggressively in order to manage their reported earnings in the fourth quarter. Our results highlight the fact that the entities with the greatest opportunity for managing care may exercise this option differentially over the year in order to manage earnings. The fourth quarter finding may be of concern to state and federal regulators to the extent that some health insurers might employ managed care mechanisms excessively at the end of the year, such that necessary services are delayed or denied.

We further analyse the disparity in MLRs across different types of managed care plans in the context of health insurance reform. The ACA provisions—many of which significantly altered the health insurer underwriting environment—appear to have affected health insurers similarly. We find that fourth quarter MLRs are higher in the post-ACA period when compared to the pre-ACA period for all insurers in our sample. Our results indicate that the fourth quarter MLRs of insurers with a greater percentage of enrollment in HMO plans relative to less managed care-intensive enrollment, are not significantly affected by the ACA.

Since its inception, managed care has had to balance the avowed objective of reducing healthcare costs with the criticism and potential legal liability that comes with imposing constraints on utilisation within the health insurance plan. The changing regulatory landscape may compel health insurers to increasingly employ opportunities to manage earnings through the management of care. Although the fourth quarter behaviour of managed care-intensive health insurers may be concerning for policymakers, they may find it reassuring that the ACA provisions do not seem to have amplified this behaviour.

Notes

An HMO plan dictates which ‘in-network’ providers may be used, and which services may be rendered. If the enrollee receives services outside of this contracted arrangement, payment on services is not rendered. Indemnity plans and other forms of managed care allow more flexibility for enrollees, and therefore a lower degree of control for insurers. For example, enrollees are not subject to the gatekeeper mechanism nor are they barred from receiving reimbursement, albeit often at a lower rate, on services rendered ‘out-of-network’ for most other managed care plans.

As managed care plans have grown over the last few decades, indemnity or fee-for-service plans have become all but obsolete in the U.S. market. In the group market, traditional indemnity plans represent one percent of plan types whereas, on average, HMOs plans represent over half of the market, alongside other types of managed care plans (Kaiser Family Foundation 2019).

Point of Service (POS) plans may also use a gatekeeper mechanism. However, these plans provide some coverage for out-of-network services which limits their ability to control losses. Our study focuses on HMO plans because these insurers have more absolute control over claims.

Of the USD 3.2 trillion spend on healthcare in 2016, private health insurance plans paid out USD 1.1 trillion on healthcare, Medicaid programs paid out USD 565.5 billion and Medicare spending totaled USD 672.1 billion (Hartman et al. 2018).

For a review of the U.S. health insurance market, including a discussion on the growth of managed care and the implications for the market, see Cutler and Zeckhauser (2000).

Other managed care mechanisms include the selection and organisation of provider networks and profiling of physicians to encourage cost-effective provision of services. See Glied (2000) for a comprehensive review of these mechanisms.

In a study conducted in 1998, 57% of physicians surveyed reported that they felt pressure from the health insurer to limit referrals, and 38% reported that their compensation included some type of incentive in the form of a bonus (Grumbach et al. 1998).

Mays et al. (2003) report that health plans in the early 2000s were increasingly seeking cost savings through new provider networks, payment systems and referral practices.

Leone and Van Horn (2005) find that non-profit hospitals adjust discretionary spending to manage earnings and significant use of discretionary accruals to meet earnings objectives. Eldenberg et al. (2011) find real activities manipulation in the non-profit hospital context, including a decrease in non-operating and non-revenue-generating expenditures. Barniv et al. (2000) find a significant decline in capital expenditures following Medicare regulation and that this could have negative long-term effects on public health.

From 2014 through 2018, a tax penalty was imposed on those who did not furnish such proof. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (2017) eliminated the tax penalty, effective 1 January 2019, though an unpenalised mandate still exists.

As of March 2019, two thirds of all Medicaid enrollees are serviced by a Medicaid managed care organisation (MCO), which is a private market health insurer required to file statutory statements to state regulators. Only five states do not utilise MCOs in the process of executing state Medicaid objectives. See Rudowitz et al. (2018) for more details regarding the current state of the Medicaid programme.

Insurers operating in the individual market reported lower performance after the exchanges opened in 2014. MLRs and losses per enrollee were significantly higher in the post-reform period and administrative expenses were significantly lower (Born and Sirmans 2018).

It was the individual/small group market exchanges and Medicaid expansion, not the individual mandate, that explain coverage gains in the post-ACA period (Frean et al. 2017).

See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (2010). In Sec. 2701, mandated adjusted community rating dictates rating of plans in the individual and small group markets “with respect to the premium rate charged by a health insurance issuer for health insurance coverage offered in the individual or small group market—such a rate shall vary with respect to the particular plan or coverage involved only by (i) whether such plan or coverage covers an individual or family; (ii) rating area; (iii) age; and (iv) tobacco use.” In Sec. 2704, the use of medical underwriting is banned through the prohibition of pre-existing condition exclusions, “a group health plan and a health insurance issuer offering group or individual health insurance coverage may not impose any preexisting condition exclusion with respect to such plan or coverage.”

See Born and Sirmans (2020) for evidence of adverse selection in the individual and group markets post-ACA.

There are several confounding factors that make direct tests related to the ACA’s MLR requirement difficult in our setting. First, the ACA’s MLR provision is administered at the insurer-state-year-line level, while we are examining aggregate insurer-level data. Second, the ACA’s MLR calculation includes components (i.e., quality improvement expenses) that are not reported prior to the ACA, making reproduction of a comparable MLR impossible. Third, the accounting treatment of incurred claims under statutory filings are different compared to reporting requirements for MLR purposes. Finally, while statutory data is reported on a calendar-year basis, MLR reports are not due until 31 March, meaning that the incentive to manipulate reported MLRs in response to MLR regulations would not appear in the fourth quarter. Therefore, while we acknowledge that MLR regulation changed during our sample period, we do not explicitly test for how this regulation influenced MLRs reported in statutory accounting statements.

The provisions discussed above suggest that health insurers have reasons to significantly change their operations and control losses post-ACA enactment. However, we recognise that the ACA also offers new opportunities for health insurers to manage risk, particularly in the individual and small group markets through state-level programmes such as the permanent risk adjustment programme, which began in 2014 and the temporary risk corridors and reinsurance programmes which were in effect from 2014 through 2016. The state-level risk adjustment programme redistributes funds from lower-risk plans to higher-risk plans in the individual and small group markets both on- and off-exchanges through payments from plans with lower actuarial risk made to plans with higher actuarial risk. The temporary state-level reinsurance programme provided payments to plans with higher-cost enrollees in the individual market from a reinsurance fund to which all health insurance issuers and self-insured plans contributed. Finally, the temporary state-level risk corridors programme limits the losses and gains of Qualified Health Plans offered on the exchanges. See Cox et al. (2016) for a comprehensive review of these three programmes.

While a profit-maximising insurer will be incentivised to manage utilisation regardless of the quarter, we argue that this perspective ignores both costs of utilisation management as well as issues regarding timing. Since utilisation management is costly (e.g. additional effort, potential reputational concerns) insurers will not intensively manage utilisation in all cases. Insurers, therefore, may only want to ramp up utilisation management when it can provide a benefit. As losses occur and are reported throughout the year, the insurer will gain information on how their performance has turned out. By waiting until the beginning of the fourth quarter to decide whether to manage utilisation (or whether they even want to), insurers can minimise potential costs while still gaining potential accounting benefits.

One potential concern in our study is whether managed care organisations (i.e. HMOs) have systematically different deductibles compared to PPOs. However, according to the Employer Health Benefits Survey of 2019, produced by Kaiser Family Foundation, the average deductible in a single coverage plan was USD 1200 for an HMO and USD 1,206 for a PPO plan. Thus, at least in single coverage plans, deductibles appear to be similar for HMOs and PPOs. While, the average deductible with family coverage for those in an aggregate structure do appear to differ (USD 861 vs. USD 1091), there is little difference in family coverage with separate per-person structure (USD 2905 vs. USD 2883). Based on this report, the assumption in our paper that HMOs and PPOs have similar deductibles seems reasonable.

Data on enrollment are from page 17, Exhibit 1—Enrollment by Product Type for Health Business Only in the annual statutory statement.

We define ‘total member months’ as all member months aside from member months in ‘PSO’ or ‘Other’ plans. Our results are robust to including PSO and Other member months in the denominator of HMO Percent.

Unlike our Mutual variable, there is no direct measure in insurer statutory statements to identify if an insurer is publicly traded. We, therefore, determine whether a group is publicly traded using data from Schedule Y Part 1, which provides information on the entire group structure for insurers. We attempt to merge this data to the merged CRSP/Compustat database (where a firm must be publicly traded if it has data in CRSP) using employer identification numbers (which are present in both Schedule Y Part 1 and Compustat). If a firm has a match, we treat it as being publicly traded.

Our results are also robust if we calculate HMO Percenti,t defining managed care as the percent of member months in both HMO and POS plans.

In untabluated tests, we also weigh each observation by total member months. Our main results are unchanged.

We also estimate this model with bootstrapped standard errors as well as with insurer fixed effects. In both cases, the results are quantitatively similar. These results are available on request.

For robustness, we estimate this model without controlling for MLR Q1, MLR Q2 and MLR Q3. Results are quantitatively similar. The results are available on request.

Even though the act was passed in 2010 and the implementation of certain provisions were staggered, minimum MLR requirements went into effect in 2011. Since minimum MLR requirements could impact fourth quarter MLRs, we define the ACA as beginning in 2011. For robustness, we re-define ACA as one if the year is 2014 or later, since 2014 represents implementation of some of the primary provisions of the ACA, including the opening of the online exchanges for individual and small group markets and the expansion of Medicaid. The results of this exercise are qualitatively similar and are available from the authors upon request.

ACA Trend is equal to 0 for all years prior to 2011, 1 in 2011, 2 in 2012, 3 in in 2013, 4 in 2014, 5 in 2015, and 6 in 2016 (the final year of our sample). Unlike our binary variable (ACA), this variable construction acknowledges that the staggered introduction of certain provisions could have differential effects over time.

References

Arlen, J., and W.B. MacLeod. 2005. Torts, expertise, and authority: Liability of physicians and managed care organizations. RAND Journal of Economics 36 (3): 494–519.

Aron-Dine, A., L. Einav, A. Finkelstein, and M. Cullen. 2015. Moral hazard in health insurance: Do dynamic incentives matter? Review of Economics and Statistics 97 (4): 725–741.

Baicker, K., S.L. Taubman, H.L. Allen, M. Bernstein, J.H. Gruber, J.P. Newhouse, E.C. Schneider, B.J. Wright, A.M. Zaslavsky, and A.N. Finkelstein. 2013. The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 368 (18): 1713–1722.

Barbaresco, S., C.J. Courtemanche, and Y. Qi. 2015. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage provision on health-related outcomes of young adults. Journal of Health Economics 40: 54–68.

Barniv, R., K. Danvers, and J. Healy. 2000. The impact of Medicare capital prospective payment regulation on hospital capital expenditures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 19 (1): 9–40.

Beaver, W.H., M.F. McNichols, and K.K. Nelson. 2003. Management of the loss reserve accrual and the distribution of earnings in the property-casualty insurance industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics 35 (3): 347–376.

Belina, H., K. Surysekar, and M. Weismann. 2019. On the medical loss ratio (MLR) and sticky selling general and administrative costs: Evidence from health insurers. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 38 (1): 53–61.

Beneish, M.D. 2001. Earnings management: A perspective. Managerial Finance 27 (12): 3–17.

Berry-Stölzle, T.R., E.M. Eastman, and X. Jianren. 2018. CEO overconfidence and earnings management: Evidence from property-liability insurers’ loss reserves. North American Actuarial Journal 22 (3): 380–404.

Born, P., and C. Geckler. 1998. HMO quality and financial performance: Is there a connection? Journal of Health Care Finance 24 (2): 65–77.

Born, P.H., and C.J. Simon. 2001. Patients and profits: The relationship between HMO financial performance and quality of care. Health Affairs 20 (2): 167–174.

Born, P.H., and E.T. Sirmans. 2020. Restrictive rating and adverse selection in health insurance. Journal of Risk and Insurance 87 (4): 919–933.

Born, P.H., and E. Sirmans. 2018. Individual market underwriting profitability in health insurance. Journal of Insurance Regulation 37 (7).

Boterenbrood, R. 2014. Income smoothing by Dutch hospitals. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 33 (5): 510–524.

Brockett, P., L. Golden, C.C. Yang, and D. Young. 2021. Medicaid managed care: Efficiency, medical loss ratio, and quality of care. North American Actuarial Journal 25 (1): 1–16.

Brot-Goldberg, Z.C., A. Chandra, B.R. Handel, and J.T. Kolstad. 2017. What does a deductible do? The impact of cost-sharing on health care prices, quantities, and spending dynamics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (3): 1261–1318.

Bryce, H.J. 1994. Profitability of HMOs: Does non-profit status make a difference? Health Policy 28 (3): 197–210.

Buchmueller, T., and J. DiNardo. 2002. Did community rating induce an adverse selection death spiral? Evidence from New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. American Economic Review 92 (1): 280–294.

Callaghan, S.R., E. Plummer, and W.F. Wempe. 2020. Health insurers’ claims and premiums under the Affordable Care Act: Evidence on the effects of bright line regulations. Journal of Risk and Insurance 87 (1): 67–93.

Cicala, S., E.M.J. Lieber, and V. Marone. 2019. Regulating markups in us health insurance. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11 (4): 71–104.

Cohen, D.A., and P. Zarowin. 2010. Accrual-based and real earnings management activities around seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (1): 2–19.

Cox, C., A. Semanskee, G. Claxton, and L. Levitt. 2016. Explaining health care reform: Risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Cutler, D.M., and R.J. Zeckhauser. 2000. The anatomy of health insurance. In Handbook of Health Economics, vol. 1, 563–643. Elsevier.

Dafny, L.S. 2010. Are health insurance markets competitive? American Economic Review 100 (4): 1399–1431.

Dechow, P., W. Ge, and C. Schrand. 2010. Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 344–401.

Degeorge, F., J. Patel, and R. Zeckhauser. 1999. Earnings management to exceed thresholds. Journal of Business 72 (1): 1–33.

Dhaliwal, D.S., C.A. Gleason, and L.F. Mills. 2004. Last-chance earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (2): 431–459.

Eastman, E.M., D.L. Eckles, and A. Van Buskirk. 2021. Accounting-based regulation: Evidence from health insurers and the Affordable Care Act. The Accounting Review 96 (2): 231–259.

Eichner, M.J. 1998. The demand for medical care: What people pay does matter. American Economic Review 88 (2): 117–121.

Einav, L., A. Finkelstein, S.P. Ryan, P. Schrimpf, and M.R. Cullen. 2013. Selection on moral hazard in health insurance. American Economic Review 103 (1): 178–219.

Eldenburg, L.G., K.A. Gunny, K.W. Hee, and N. Soderstrom. 2011. Earnings management using real activities: Evidence from nonprofit hospitals. The Accounting Review 86 (5): 1605–1630.

Foster, G. 1977. Quarterly accounting data: Time-series properties and predictive-ability results. The Accounting Review 1–21.

Frean, M., J. Gruber, and B.D. Sommers. 2017. Premium subsidies, the mandate, and Medicaid expansion: Coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Health Economics 53: 72–86.

Glied, S. 2000. Managed care. In Handbook of health economics, vol. 1, 707–753. Elsevier.

Grace, M.F., and J.T. Leverty. 2010. Political cost incentives for managing the property-liability insurer loss reserve. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (1): 21–49.

Grumbach, K., D. Osmond, K. Vranizan, D. Jaffe, and A.B. Bindman. 1998. Primary care physicians’ experience of financial incentives in managed-care systems. New England Journal of Medicine 339 (21): 1516–1521.

Hall, M.A. 1988. Institutional control of physician behavior: Legal barriers to health care cost containment. University of Pa. Law of Review 137: 431.

Hall, M.A. 1989. The malpractice standard under health care cost containment. Law, Medicine and Health Care 17 (4): 347–355.

Hall, M.A., B. Zheng, E. Dugan, F. Camacho, K.E. Kidd, A. Mishra, and R. Balkrishnan. 2002. Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providers. Medical Care Research and Review 59 (3): 293–318.

Havighurst, C.C. 2000. Vicarious liability: Relocating responsibility for the quality of medical care. American Journal of Law & Medicine 26: 7.

Harrington, S.E. 2010. US health-care reform: The patient protection and affordable care act. Journal of Risk and Insurance 77 (3): 703–708.

Hartman, M., A.B. M., N. Espinosa, A. Catlin, and National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. 2018. National health care spending in 2016: Spending and enrollment growth slow after initial coverage expansions. Health Affairs 37 (1): 150–160.

Healy, P.M., and J.M. Wahlen. 1999. A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons 13 (4): 365–383.

Hellinger, F.J. 1995. Selection bias in HMOs and PPOs: A review of the evidence. Inquiry 135–142.

Hellinger, F.J. 1998. The effect of managed care on quality: A review of recent evidence. Archives of Internal Medicine 158 (8): 833–841.

Higgins, M.L., and P.D. Thistle. 2000. Capacity constraints and the dynamics of underwriting profits. Economic Inquiry 38 (3): 442–457.

Hurley, R.E., B.C. Strunk, and J.S. White. 2004. The puzzling popularity of the PPO. Health Affairs 23 (2): 56–68.

Jacobson, C.K. 1994. Investor response to health care cost containment legislation: Is American health policy designed to fail? Academy of Management Journal 37 (2): 440–452.

Jacob, J., and B.N. Jorgensen. 2007. Earnings management and accounting income aggregation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 43 (2–3): 369–390.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2019. Employer health benefits 2019 annual survey. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-Annual-Survey-2019. Accessed 17 Feb 2021.

Leone, A.J., and R.L. Van Horn. 2005. How do nonprofit hospitals manage earnings? Journal of Health Economics 24 (4): 815–837.

Manning, W.G., and M.S. Marquis. 1996. Health insurance: The tradeoff between risk pooling and moral hazard. Journal of Health Economics 15 (5): 609–639.

Mayers, D., and C.W. Smith, Jr. 1981. Contractual provisions, organizational structure, and conflict control in insurance markets. Journal of Business 54 (3): 407–434.

Mays, G.P., R.E. Hurley, and J.M. Grossman. 2003. An empty toolbox? Changes in health plans’ approaches for managing costs and care. Health Services Research 38 (1–2): 375–393.

Mechanic, D., and M. Schlesinger. 1996. The impact of managed care on patients’ trust in medical care and their physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association 275 (21): 1693–1697.

Mensah, Y.M., J.M. Considine, and L. Oakes. 1994. Statutory insolvency regulations and earnings management in the prepaid health-care industry. The Accounting Review 70–95.

Miller, R.H., and H.S. Luft. 1994. Managed care plan performance since 1980: A literature analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association 271 (19): 1512–1519.

Miller, R.H., and H.S. Luft. 1997. Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16 (5): 7–25.

Miller, R.H., and H.S. Luft. 2002. HMO plan performance update: An analysis of the literature, 1997–2001. Health Affairs 21 (4): 63–86.

Mittelstaedt, H.F., W.D. Nichols, and P.R. Regier. 1995. SFAS No. 106 and benefit reductions in employer-sponsored retiree health care plans. The Accounting Review 70 (4): 535–556.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners. 2011. Adverse selection issues and health insurance exchanges under the Affordable Care Act. https://www.naic.org/store/free/ASE-OP.pdf. Accessed 5 July 2018.

Nelson, K.K. 2000. Rate regulation, competition, and loss reserve discounting by property-casualty insurers. The Accounting Review 75 (1): 115–138.

Protection, Patient, and Affordable Care Act. 2010. Patient protection and affordable care act. Public Law 111 (48): 759–762.

Pauly, M.V. 1998. Managed care, market power, and monopsony. Health Services Research 33 (5 Pt 2): 1439.

Petroni, K.R. 1992. Optimistic reporting in the property-casualty insurance industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics 15 (4): 485–508.

Roychowdhury, S. 2006. Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42 (3): 335–370.

Rudowitz, R., R. Garfield, and E. Hinton. 2018. 10 things to know about Medicaid: Setting the facts straight. Kaiser Family Foundation 12. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-medicaid-setting-the-facts-straight/. Accessed 7 March 2019.

Scanlon, D.P., and M. Chernew. 2000. Managed care and performance measurement: Implications for insurance markets. North American Actuarial Journal 4 (2): 128–138.

Schessler, C.E. 1992. Liability implications of utilization review as a cost containment mechanism. Journal of Contemporary Health Law and Policy 8: 379.

Schield, J., J.J. Murphy, and H.J. Bolnick. 2001. Evaluating managed care effectiveness: A societal perspective. North American Actuarial Journal 5 (4): 95–111.

Simonet, D. 2005. Patient satisfaction under managed care. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 18 (6): 424–440.

Sommers, B.D., M.Z. Gunja, K. Finegold, and T. Musco. 2015. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. Journal of the American Medical Association 314 (4): 366–374.

Strange, M.L., and J.R. Ezzell. 2000. Valuation effects of health cost containment measures. Journal of Health Care Finance 27 (1): 54–66.

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. 2017. Tax cuts and job act. Public Law. 2017. No. 115-97.

Vansant, B. 2016. Institutional pressures to provide social benefits and the earnings management behavior of nonprofits: Evidence from the US hospital industry. Contemporary Accounting Research 33 (4): 1576–1600.

Weech-Maldonado, R. 2002. Impact of HMO mergers and acquisitions on financial performance. Journal of Health Care Finance 29 (2): 64–64.

Winter, R.A. 1994. The dynamics of competitive insurance markets. Journal of Financial Intermediation 3 (4): 379–415.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Born, P.H., Eastman, E.M. & Sirmans, E.T. Managed care or carefully managed? Management of underwriting profitability by health insurers. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 48, 5–31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-021-00239-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-021-00239-1