Abstract

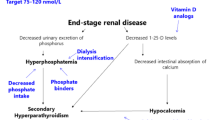

Hyperphosphataemia is prevalent among chronic renal failure and dialysis patients. It is known to stimulate parathyroid hormone and suppress vitamin D3 production, thereby inducing hyperparathyroid bone disease. In addition, it may independently contribute to cardiac causes of death through increased myocardial calcification and enhanced vascular calcification. Hyperphosphataemia is also associated with cardiac microcirculatory abnormalities. Therefore, phosphate control is of prime importance.

It is important to control phosphate levels early in the course of chronic renal failure in order to avoid and treat secondary hyperparathyroidism, and cardiovascular and soft tissue calcifications. Dietetic restrictions are often difficult to follow long term. Because of its large sphere of hydration and the complex kinetics of phosphate elimination, phosphate is not easily removed by dialysis. Long, slow dialysis may be effective, but this needs logistics and acceptance by patients. Thus, oral phosphate binders are generally required to control serum levels. None of the existing phosphate binding agents is truly satisfactory. Aluminium-containing agents are highly efficient but many clinicians have abandoned their use because of the potential toxicity. Despite of the wide use of calcium-containing agents, there was a link with hypercalcaemia and soft tissue calcifications. Novel phosphate binders in the form of polyallylamine hydrochloride, polyuronic acid derivatives and lanthanum carbonate appear promising. In this review, we discuss causes of hyperphosphataemia, pathological consequences and modalities of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE. Association of serum phosphorus and calcium X phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic haemodialysis patients: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 31: 607–17

Lowrie EG, Lew NL. death risk in haemodialysis patients: the predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am J Kidney Dis 1990; 15: 458–82

Delmez J, Slatopolsky E. Hyperphosphataemia: its consequences and treatment in patients with chronic renal disease. Am J Kid Dis 1992; 4: 303–17

Chan JCM, Bell N. Disorders of phosphate metabolism. In: Chan JCM, Gill JR, editors. Kidney electrolyte disorders. New York: Churchill Livingston, 1990: 223–60

Lee DBN, Kurokawa K. Physiology of phosphorus metabolism. In: Maxwell MH, Kleeman CR, Narins RG, editors. Clinical disorders of fluid electrolyte metabolism. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987: 245

Malluche HH, Monier-Faugere MC. Understanding and managing hyperphosphataemia in patients with chronic renal disease. Clin Nephrol 1999; 52(5): 267–77

Bijvoet OLM. Relation of plasma phosphorus concentration to renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate. Clin Sci 1969; 37: 26

Walton RJ, Bijvoet OLM. Nomogram for the derivation of renal threshold phosphate concentration. Lancet 1975; II: 309–10

Slatopolsky E, Robson AM, Elkan AM, et al. Control of phosphate excretion in uraemic man. J Clin Invest 1968; 47: 1865–74

Hruska KA, Teitelbaum SL. Mechanisms of disease: renal osteodystrophy. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 166–75

Brautbar N, Kleeman CR. Hypophosphataemia and hyperphosphataemia: clinical and pathological aspects. In: Maxwell MH, Kleeman CR, Narins RG, editors. Clinical disorders of fluid electrolyte metabolism. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987: 789

BrickerNS, Slatopolsky E, Reiss E, et al. Calcium, phosphorus and bone in renal disease and transplantation. Arch Intern Med 1969; 123: 543–53

Slatopolsky E. Phosphate restriction prevents parathyroid cell growth in uremic rats and high phosphate directly stimulates PTH secretion in tissue culture. J Clin Invest 1996; 97: 2534–40

Almaden Y. High phosphate directly stimulates PTH secretion and synthesis by human parathyroid tissue. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998; 9: 1845–52

Kilav R, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. Parathyroid hormone gene expression in hypophosphatemic rats. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 327–33

Almaden Y, Canalejo A, Ballesteros E, et al. Regulation of arachidonic acid production by intracellular calcium in parathyroid cells: effect of extracellular phosphate. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002 Mar; 13(3): 693–8

Hernandez A. High phosphate diet increases prepro PTH mRNA independent of calcium and calcitriol in normal rats. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 1872–8

Slatopolsky E, Caglar S, Pennell JP, et al. On the pathogenesis of hyperparathyroidism in chronic experimental insufficiency in the dog. J Clin Invest 1971; 50: 492–9

Naveh-Many T, Silver J. Regulation of parathyroid hormone gene expression by hypocalcaemia, hypercalcaemia, and vit D in the rat. J Clin Invest 1990; 86: 1313–9

Silver J, Moallem E, Kilav R, et al. New insights into the regulation of parathyroid hormone synthesis and secretion in chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11: 2–5

Naveh-Many T, Rahaminov R, Livni N, et al. Parathyroid cell proliferation in normal and chronic renal failure rats: the effects of calcium, phosphate and vit D. J Clin Invest 1995; 96: 1786–93

Naveh-Many T, Friedlaender MM, Mayer H, et al. Calcium regulates parathyroid hormone messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), but not calcitonin mRNA in vivo in the rat. Dominant role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Endocrinology 1989; 125: 275–80

Silver J, Sela SB, Naveh-Many T, et al. Regulation of parathyroid cell proliferation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1997; 6: 321–6

Moallem E, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. Post-transcriptional regulation of PTH gene expression by hypocalcaemia due to protein binding to the PTH mRNA 3’ UTR [abstract]. J Bone Miner Res 1995; 10: 142

Moallem E, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. RNA-protein binding and post-transcriptional regulation of parathyroid hormone gene expression by calcium and phosphate. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 5253–9

Prafitt AM. Soft tissue calcification in uraemia. Arch Intern Med 1969; 124: 544–55

Selye H. Calciphylaxis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962

Gipstein RM, Coburn JW, Adama DA, et al. Calciphylaxis in man. Arch Intern Med 1976; 136: 1273–80

Androgue HJ, Frazier MR, Zeluff B, et al. Systemic calciphylaxis: successful treatment with parathyroidectomy. J Urol 1983; 129: 362–3

Massry SG, Coburn JW, Hartenbower DL, et al. Mineral content of human skin in uraemia: effect of secondary hyperparathyroidism and haemodialysis. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 1970; 7: 146–8

Almaden Y, Canalejo A, Ballesteros E, et al. Effects of high extracellular phosphate concentration on arachidonic acid production by parathyroid tissue in vitro. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000 Sep; 11(9): 1712–8

Katz AI, Hampers CL, Merrill JP. Secondary hyperparathyroidism and renal osteodystrophy in chronic renal failure: analysis of 195 patients, with observations on effects of chronic dialysis, kidney transplantation and subtotal parathyroidectomy. Medicine 1969; 48: 333–74

Hsu CM, Patel S. Factors influencing calcitriol metabolism in renal failure. Kidney Int 1990; 37: 44–50

Hsu CM, Patel SR, Young EW. Mechanism of decreased calcitriol degradation in renal failure. Am J Physiol 1992; 262: F192–8

Dusso A, Lopez-Hilker S, Lewis-Fich J, et al. Metabolic clearance rate and production rate of calcitriol in uraemia. Kidney Int 1989; 35: 860–4

Korkor AB. Reduced binding of 3 (H) 1,25-dihydroxyvit D3 in the parathyroid glands of patients with renal failure. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1573–7

Dusso A, Lopez-Hilker S, Rapp N, et al. Extra-renal production of calcitriol in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 1988; 34: 368–75

Dusso A, Finch J, Delmez J, et al. Extrarenal production of calcitriol. Kidney Int 1990; 38: S36–40

Brown AJ, Berkoben M, Ritter CS, et al. Binding and metabolism of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in cultured parathyroid cells. Endocrinology 1992; 130: 276–81

US Renal Data System: annual data report. Bethesda (MD): The National Institutes of Health. National Instate of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 1999

Block GA, Port FK. Re-evaluation of risks associated with hyperphosphataemia and hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients: recommendations for a change in management. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35: 1226–37

Block GA. Prevalence and clinical consequences of elevated Ca X P product in haemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2000; 54: 318–24

Giachelli CM, Shuichi J, Shioi A, et al. Vascular calcification and inorganic phosphate. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 38(4) Suppl. 1: S34–7

London GM, Guerin AP, Marchis SJ, et al. Cardiac and arterial interactions in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 600–8

Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, et al. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2001 Oct; 38(4): 938–42

Kuzela DC, Huffer WE, Conges JD, et al. Soft tissue calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Pathol 1977 Feb; 86(2): 403–24

Ribeiro S, Ramos A, Brandao A, et al. Cardiac valve calcification in haemodialysis patients: role of calcium-phosphate metabolism. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13(8): 2037–40

Achenbach S, Moshage W, Ropers D, et al. Value of electron-beam computed tomography for the non-invasive detection of high-grade coronary artery stenoses and occlusion. N Engl J Med 1998; 31: 1964–71

Guerin AP, London GM, Marchais SJ, et al. Arterial stiffening and vascular calcifications in end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15(7): 1014–21

Mourad JJ, Girerd X, Boutouyrie P, et al. Increased stiffness of radial artery wall material in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 1997, 30

Schwarz U, Buzello M, Ritz E, et al. Morphology of coronary atherosclerotic lesions in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 218–33

Amann K, Ritz E. Microvascular disease-the Cinderella of uremic heart disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 1493–503

Clyne N, Lins LE, Pehrsson SK. Occurrence and significance of heart disease in uraemia: an autopsy study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1986; 20: 307–11

Braun J, Oldendrof M, Heilder R, et al. Electron beam computed tomography in the evaluation of cardiac calcification in chronic dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996; 27: 394–401

Raine AE. Acquired aortic stenosis in dialysis patients. Nephron 1994; 68: 159–68

Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342(20): 1478–83

Goldsmith DJ, Covic A, Sambrook PA, et al. Vascular calcification in long-term haemodialysis patients in a single unit: a retrospective analysis. Nephron 1997; 77: 37–43

Nisizawa Y, Shoji T, Kawagishi T, et al. Atherosclerosis in uraemia: possible roles of hyperparathyroidism and intermediate density lipoprotein accumulation. Kidney Int 1997; 52 Suppl. 62: S90–2

Bro S, Olgaard K. Effects of excess PTH on nonclassical target organs. Am J Kidney Dis 1997; 30(5): 606–20

Ganesh SK, Stack AG, Levin NW, et al. Association of elevated serum PO4, Ca X P product, and parathyroid hormone with cardiac mortality risk in chronic haemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 12: 2125–30

Alfrey AC, Solomons CC, Ciricillo J, et al. Extraosseous calcification: evidence of pyrophosphate metabolism in uremia. J Clin Invest 1976; 57: 692–9

Stivelman JC. Refractoriness to recombinant human epoetin treatment. In: Nissenson AR, Fine RN, editors. Dialysis therapy. St Louis (MO): Mosby-Year Book, 1993: 236

Daculsi G, Bouler JM, LeGeros RZ. Adaptive crystal formation in normal and pathological calcifications in synthetic calcium phosphate and related biomaterials. Int Rev Cytol 1997; 172: 129–91

Rose BD, Rush JM, eds. Nephrology and hypertension. Available from URL: http://www.uptodate.com [Accessed 2003 Jan 29]

Davison AM, ed. Oxford textbook of clinical nephrology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998

Levine NW, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Strawderman RL. Which causes of death are related to hyperphosphataemia in haemodialysis (HD) patients? [abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998: 217A

Raggi P. Detection and quantification of cardiovascular calcifications with electron beam tomography to estimate risk in haemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2000; 54(4): 325–33

Amann K, Gross ML, London GM, et al. Hyperphosphataemia-a silent killer of patients with renal failure? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 2085–7

Rumberger JA, Brundage BH, Rader DJ, et al. Electron beam computed tomographic coronary calcium scanning: a review and guidelines for use in asymptomatic persons. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 243–52

Feest T, Ansell D. Serum calcium, phosphate and parathyroid hormone. London: The UK Renal Registry, 2000 Dec: 99–111

Kopple JD, Coburn JW. Metabolic studies of low protein diets in uraemia: II. calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. Medicine (Baltimore) 1973; 52: 597–607

Rufino M, Bonis ED, Martin M, et al. Is it possible to control hyperphosphataemia with diet, without inducing protein malnutrition? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13 (Suppl. 3): 65–7

Coburn JW. Mineral metabolism and renal bone disease: effects of CAPD versus haemodialysis. Kidney Int 1993; 43 (Suppl. 40): S92–S100

Delmez JA, Slatopolsky E, Martin KJ, et al. Minerals, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 1982; 21: 862–7

Cannata JB, Briggs JD, Fell GS, et al. Comparison of control serum phosphate levels during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and during haemodialysis. Perit Dial Bull 1983; 3: 97–8

Zuccheli P, Santoro A. Inorganic phosphate removal during different dialytic procedures. Int J Artif Organs 1987; 10: 173–8

Zehnder C, Gutzwiller JP, Renggli K. Haemodiafiltration: a new treatment option for hyperphosphataemia in haemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1999 Sep; 52(3): 152–9

Haas T, Hillion D, Dongradi G. Phosphate kinetics in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1991; 6 Suppl. 2: S108–13

Charra B, Calemard E, Ruffet M, et al. Survival as an index of adequacy of dialysis. Kidney Int 1992; 41: 1286–91

Kooistra MP, Vos J, Koomans HA, et al. Daily home haemodialysis in the Netherlands: effects on metabolic control, haemodynamics, and the quality of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13: 2853–60

Spalding EM, Chamney PW, Farrington K. Phosphate kinetics during haemodialysis: evidence for biphasic regulation. Kidney Int 2002 Feb; 61(2): 655–62

Mucsi I, Hercz G, Uldall R, et al. Control of serum phosphate without any phosphate binders in patients treated with nocturnal haemodialysis. Kidney Int 1998; 53: 1399–404

Fernandez E, Montoliu J. Successful treatment of massive uraemic tumoral calcinosis with daily haemodialysis and very low calcium dialysate. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994; 9(8): 1207–9

Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Norwood K, et al. Long-term effects of calcium carbonate and 2.5 m Eq/1 calcium dialysate on mineral metabolism. Kidney Int 1989; 36: 897–903

Cunningham J. Reduced calcium dialysate in CAPD patients: efficacy and limitations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997 Jun; 12(6): 1223–8

Bender FH, Bernardini J, Piraino B. Calcium mass transfer with dialysate containing 1.25 and 1.75 mmol/L calcium in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1992 Oct; 20(4): 367–71

Hutchison AJ, Freemont AJ, Boulton HF, et al. Low-calcium dialysis fluid and oral calcium carbonate in CAPD: a method of controlling htperphosphataemia whilst minimizing aluminium exposure and hypercalcaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1992; 7: 1219–25

Argiles A, Kerr PG, Canaud B, et al. Calcium kinetics and the long-term effects of lowering dialysate calcium concentration. Kidney Int 1993; 43: 630–40

Weinreich T, Ritz E, Passlick-Deetjen J, et al. Long-term dialysis with low calcium solution (1.0 mmol/L) in CAPD: effects on bone mineral metabolism. Perit Dial Int 1996; 16: 260–8

Gokal R. The preferred phosphate binder in dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19: 405–8

Schiller L, Santa A, Sheikh M, et al. Effect of the time of administration of calcium acetate on phosphorus binding. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 1110–3

Moriniere PH, Roussel A, Tahiri Y, et al. Substitution of aluminium hydroxide by high doses of calcium carbonate in patients on chronic haemodialysis: disappearance of hyper-aluminiumaemia and equal control of hyperparathyroidism. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 1983; 19: 784–7

Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Lopez-Itilker S, et al. Calcium carbonate as a phosphate binder in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 157–61

Mai M, Emmett M, Sheikh M, et al. Calcium acetate, an effective phosphorus binder in patients with renal failure. Kidney Int 1989; 36: 690–5

Shaefer K, Scheer J, Asmus G, et al. The treatment of uraemic hyperphosphataemia with calcium acetate and calcium carbonate: a comparative study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1991; 6: 170–5

Sheikh MS, Maguire JA, Emmett M, et al. Reduction of dietary phosphorus absorption by phosphate binders: theoretical, in vitro and in vivo study. J Clin Invest 1989; 83: 66–73

Janssen MJ A, Kuy AV, Ter Wee PM, et al. Aluminium hydroxide, calcium carbonate and calcium acetate in chronic intermittent haemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1996; 45(2): 111–9

Schaefer K. Alternative phosphate binders: an update. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1993; 1: 35–9

Korbin SM, Goldstein SJ, Shangraw RF, et al. Variable efficacy of calcium carbonate tablets. Am J Kidney Dis 1989; 14: 461–5

Molitoris BA, Froment DH, Mackenzie TA, et al. Citrate: a major factor in the toxicity of orally administered aluminium compounds. Kidney Int 1989; 36: 949–53

Schneider HW, Kulbe KD, Weber H, et al. In vitro and in vivo studies with a non-aluminium phosphate-binding compound. Kidney Int Suppl 1986; 18: S120–3

Passlick J, Wilhelm M, Busch TH, et al. Calcium alginate, an aluminium: free phosphate binder, in patients on CAPD. Clin Nephrol 1989; 32(2): 96–100

Riedel E, Hampl H. Steudle V. Calcium-alpha-ketoglutarate administration to malnourished haemodialysis patients improves plasma argenine concentrations. Miner Electrolyte Metab 1996; 22: 119–22

Zimmermann E, Wassmer S, Steudle V. Long-term treatment with calcium-alpha-ketoglutarate corrects secondary hyperparathyroidism. Miner Electrolyte Metab 1996; 22(1-3): 196–9

Macia M, Cornel F, Navarro JF, et al. Calcium salts of keto-amino acids: a phosphate binder alternative for patients on CAPD. Clin Nephrol 1997 Sep; 48(3): 181–4

Brick R, Zimmermann E, Wassmer S, et al. Calcium keto-glutarate versus calcium acetate for treatment of hyperphosphataemia in patients on maintenance haemodialysis: a crossover study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 1475–9

Bro S, Rasmussen RA, Handberg J, et al. Randomised crossover study comparing the phosphate binding efficacy of calcium ketoglutarate versus calcium carbonate in patients on chronic haemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 2: 257–62

Alfrey AC. Aluminium metabolism. Kidney Int 1986; 18 Suppl.: S8–11

Salusky IB, Foley J, Nelson P, et al. Aluminium accumulation during treatment with aluminium hydroxide and dialysis in children and young adults with chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 527–31

Slatopolsky E. The interaction of parathyroid hormone and aluminium on renal osteodystrophy. Kidney Int 1987; 31: 842–54

McCarthy J, Milliner D, Johnson W. Clinical experience with desferrioxamine in dialysis patients with aluminium toxicity. Q J Med 1990; 74: 257–76

Jenkins DA, Gouldesbrough D, Smith GD, et al. Can low-dosage aluminium hydroxide controls the plasma phosphate without bone toxicity? Nephrol Dial Transplant 1989; 4: 51–6

Canterbury JM, Bricker NA, Levey GS. Metabolism of bovine parathyroid Hormone: immunological and biological characteristics of fragments generated by liver perfusion. J Clin Invest 1975; 55: 1245–52

Llach F, Bover J. al osteodystrophies In: Brenner BM, Rector FC, editors. Brenner & Rector’s the kidney. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders Company, 2000: 2103–86

O’Donovan R, Baldwin D, Hammer, et al. ubstitution of aluminium salts by magnesium salts in control of dialysis hyperphosphataemia. Lancet 1986; I: 880–1

Parsons V, Baldwin D, Moniz C, et al. Successful control of hyperpparathyroidism inpatients on CAPD using magnesium carbonate and calcium carbonate as phosphate binders. Nephron 1993; 63: 79–83

Hergesell O, Ritz E. Stabilized polynuclear iron hydroxide is an efficient oral phosphate binder in uraemic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 863–7

Weaver CM, Schulze DG, Peck LW, et al. Phosphate-binding capacity of ferrihydrite versus calcium acetate in rats. Am J Kidney Dis 1999 Aug; 34(2): 324–7

Spengler K, Follmann H, Boos KS, et al. Cross-linked iron dextran is an efficient oral phosphate binder in the rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11: 808–12

Graff L, Burnel D. Reduction of dietary phosphorus absorption by oral Phosphorus binders. Res Common Mol Pathol Pharmacol 1995 Dec; 90(3): 389–401

Slatopolsky E, Burke SK, Dillon MA, et al. RenaGel, a nonab-sorbed calcium-and aluminium-free phosphate binder, lowers serum phosphorus and parathyroid hormone. Kidney Int 1999; 55: 299–307

Chertow GM, Burke SK, Lazarus JM, et al. Poly[allylamine hydrochloride] (RenaGel): a noncalcaemic phosphate binder for the treatment of hyperphosphataemia in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 1997; 29: 66–71

Goldberg DI, Dillon MA, Slatopolsky E, et al. Effect of RenaGel, a non-absorbed, calcium-and aluminium-free phosphate binder, on serum phosphorus, calcium, and intact parathyroid hormone in end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13: 2303–10

Chertow GM, Dillon M, Burke SK, et al. A randomised trial of sevelamer hydrochloride (RenaGel) with and without supplemental calcium-strategies for the control of hyperphosphataemia and hyperparathyroidism in haemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1999; 51: 18–26

Bleyer AJ, Burke SK, Dillon M, et al. A comparison of the calcium-free phosphate binder sevelamer hydrochloride with calcium acetate in the treatment of hyperphosphataemia in haemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 33: 694–701

Wiles BM, Reiner D, Kern M, et al. Simultaneous lowering of serum phosphate and LDL-cholesterol by sevelamer hydrochloride (RenaGel) in dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1998; 50: 381–6

Raggi P, Burke SK, Dillon MA, et al. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification compared to calcium-based phosphate binders [abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: A1232

Chertow GM, Burke SK, Dillon MA, et al. for the RenaGel study group. Long-term effects of sevelamer hydrochloride on the calcium x phosphate product and lipid profile of haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14(12): 2907–14

Hergesell O, Ritz E. Phosphate binders in uraemia: pharmaco-dynamics, pharmacoeconomics, and pharmacoethics. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17: 14–7

Hutchison AJ. Calcitriol, lanthanum carbonate and other new phosphate Binders in the management of renal osteodystrophy. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19 Suppl. 2: S408–12

Behets GJ, Dams S, Damment C, et al. assessment of the effects of lanthanum on bone in a chronic renal failure (CRF) rat model [abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: A3862

Albaaj F, Hutchison AJ. Lanthanum carbonate: a novel noncalcaemic phosphate binder in dialysis patients [abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000, A2941

Murer H, Biber J. Molecular mechanisms in renal phosphate reabsorption. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995; 10: 1501–4

Brooks DP, Ali SM, Contino LC, et al. Phosphate excretion and phosphate transporter messanger RNA in uraemic rats treated with phosphonoformic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 281: 1440–5

Vanhofer R, Veys N, Van Biesen W, et al. Alternative timeframes for haemodialysis. Artif Organs 2002 Feb; 26(2): 160–2 Correspondence and offprints: Dr Alastair J. Hutchison, Manchester Institute of Nephrology and Transplantation, The Royal Infirmary, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9WL, UK. E-mail: alastair.hutchison@cmmc.nhs.uk

Acknowledgements

Dr Hutchison has a consultancy agreement with Shire Pharmaceutical Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albaaj, F., Hutchison, A.J. Hyperphosphataemia in Renal Failures. Drugs 63, 577–596 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363060-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200363060-00005