Abstract

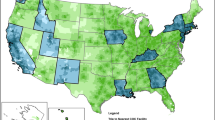

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) offer primary and preventive healthcare, including cancer screening, for the nation’s most vulnerable population. The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between access to FQHCs and cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs). One-way analysis of variance was conducted to compare the mean MIRs for breast, cervical, prostate, and colorectal cancers for each U.S. county for 2006–2010 by access to FQHCs (direct access, in-county FQHC; indirect access, adjacent-county FQHC; no access, no FQHC either in the county or in adjacent counties). ArcMap 10.1 software was used to map cancer MIRs and FQHC access levels. The mean MIRs for breast, cervical, and prostate cancer differed significantly across FQHC access levels (p < 0.05). In urban and healthcare professional shortage areas, mean MIRs decreased as FQHC access increased. A trend of lower breast and prostate cancer MIRs in direct access to FQHCs was found for all racial groups, but this trend was significant for whites only. States with a large proportion of rural and medically underserved areas had high mean MIRs, with correspondingly more direct FQHC access. Expanding FQHCs to more underserved areas and concentrations of disparity populations may have an important role in reducing cancer morbidity and mortality, as well as racial-ethnic disparities, in the United States.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel, R., Ma, J., Zou, Z., & Jemal, A. (2014). Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64(1), 9–29.

Schoen, R. E., Pinsky, P. F., Weissfeld, J. L., et al. (2012). Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(25), 2345–2357.

Tabár, L., Vitak, B., Chen, T. H., et al. (2011). Swedish two-county trial: Impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology, 260(3), 658–663.

Tangen, C. M., Hussain, M. H., Higano, C. S., et al. (2012). Improved overall survival trends of men with newly diagnosed M1 prostate cancer: a SWOG phase III trial experience (S8494, S8894 and S9346). Journal of Urology, 188(4), 1164–1169.

Saslow, D., Solomon, D., Lawson, H. W., et al. (2012). American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 62(3), 147–172.

Simard, E. P., Naishadham, D., Saslow, D., & Jermal, A. (2012). Age-specific trends in black–white disparities in cervical cancer incidence in the United States: 1975–2009. Gynecologic Oncology, 127(3), 611–615.

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D., & Jemal, A. (2012). Cancer statistics for hispanics/latinos, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 62(5), 283–298.

Hopenhayn, C., Bush, H., Christian, A., & Shelton, B. J. (2005). Comparative analysis of invasive cervical cancer incidence rates in three Appalachian states. Preventive Medicine, 41(5), 859–864.

Shin, P., Rosenbaum, S., Paradise, J. (2012). Community health centers: The challenge of growing to meet the need for primary care in medically underserved communities. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/DHP_Publications/pub_uploads/dhpPublication_3B043800-5056-9D20-3D5DCAA18AC4BD43.pdf.

Bureau of Primary Health Care, US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. HRSA geospatial data warehouse. http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/HRSAActivityStatus.aspx. Accessed September 3, 2013.

Human Resources and Service Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. Health centers and the affordable care act fact sheet. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/healthcenterfactsheet.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2014.

Hébert, J. R., Daguise, V. G., Hurley, D. M., et al. (2009). Mapping cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios to illustrate racial and sex disparities in a high-risk population. Cancer, 115(11), 2539–2552.

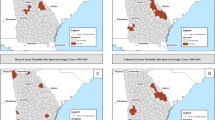

Wagner, S. E., Hurley, D. M., Hébert, J. R., McNamara, C., Bayakly, A. R., & Vena, J. E. (2012). Cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios in Georgia. Cancer, 118(16), 4032–4045.

National Cancer Institute. State Cancer Profiles: Dynamic views of cancer statistics for prioritizing caner control efforts in the nation, states, and counties. http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/index.html. Accessed September 3, 2013.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Area Resource File (ARF). http://www.arfsys.com. Accessed September 2, 2012.

U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey. http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/data_main/. Accessed October 25, 2013.

Bodenheimer, T., & Pham, H. H. (2010). Primary care: Current problems and proposed solutions. Health Affairs, 29(5), 799–805.

National Association of Community Health Centers. (2013). A sketch of community health centers: Chart book. http://www.nachc.com/client/Chartbook2013.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2013.

Shi, L., & Stevens, G. D. (2007). The role of community health centers in delivering primary care to the underserved: experiences of the uninsured and Medicaid insured. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 30(2), 159–170.

Starfield, B., Powe, N. R., Weiner, J. R., et al. (1994). Costs vs quality in different types of primary care settings. JAMA, 272(24), 1903–1908.

Probst, J. C., Laditka, S. B., Wang, J. Y., & Johnson, A. O. (2007). Effects of residence and race on burden of travel for care: Cross sectional analysis of the 2001 US National Household Travel Survey. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 40.

Pucher, J., & Renne, J. L. (2005). Rural mobility and mode choice: Evidence from the 2001 National Household Travel Survey. Transportation, 32(2), 165–186.

Jemal, A., Siegel, R., Xu, J., & Ward, E. (2010). Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60(5), 277–300.

Moyer, V. A. (2012). Screening for prostate cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 157(2), 120–134.

Adams, S. A., Fleming, A., Brandt, H. M., et al. (2009). Racial disparities in cervical cancer mortality in an African American and European American cohort in South Carolina. Journal-South Carolina Medical Association, 105(7), 237–244.

Moyer, A., Sohl, S. J., Knapp-Oliver, S. K., & Schneider, S. (2009). Characteristics and methodological quality of 25 years of research investigating psychosocial interventions for cancer patients. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 35(5), 475–484.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U48/DP001936 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Prevention Research Centers) and the National Cancer Institute (PIs: Dr. Hébert, Dr. Friedman). This work also was partially supported by: an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention and Control from the Cancer Training Branch of the NCI to Dr. Hébert (K05 CA136975), U54 CA153461-01 from the National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (Community Networks Program) to the South Carolina Cancer Disparities Community Network-II (SCCDCN-II), and an NCI K01 Career Development Grant to Dr. Tucker-Seeley (K01 CA169041). Dr. Yip was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA 124397; PI: S-P Tu).

Conflict of interest

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10900_2014_9978_MOESM1_ESM.eps

Figure S1. Access to FQHCs and colorectal cancer MIRs by region. (a) West, (b) Midwest, (c) Northeast, (d) Southwest, (e) Southeast. Supplementary material 1 (EPS 4107 kb)

10900_2014_9978_MOESM2_ESM.eps

Figure S2. Access to FQHCs and prostate cancer MIRs by region. (a) West, (b) Midwest, (c) Northeast, (d) Southwest, (e) Southeast. Supplementary material 2 (EPS 4107 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, S.A., Choi, S.K., Khang, L. et al. Decreased Cancer Mortality-to-Incidence Ratios with Increased Accessibility of Federally Qualified Health Centers. J Community Health 40, 633–641 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9978-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9978-8