Abstract

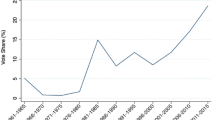

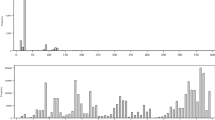

As numerous studies in the US and elsewhere document, voters often hold incumbents accountable for recent economic circumstances. However, our knowledge of the conditions that allow voters to do so remains incomplete. In particular, most findings about economic voting come from studies of modern economies (post World War II). Modern economies have a host of characteristics that seem to lend themselves to economic voting. Their governments play a large role in the economy and have the Keynesian toolset necessary to influence the economy. Their voters are educated and have access to detailed economic data from ubiquitous media. Are these and other modern conditions necessary for economic voting? Would voters still hold politicians accountable even under adverse conditions? Using economic measures now available back to the 1790s, we study economic voting from the earliest days of the US Republic when none of these conditions were met. Voters, we find, appear to judge incumbent presidents on the economy all the way back to George Washington. Consistent with this pattern, we also find that the economy appears to shape presidents' decisions to run again throughout US history. These findings support recent comparative evidence that economic voting is pervasive across a variety of contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Replication materials for this study can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DTSJUI.

Note that Jacobson and Kellner (1981) make a similar argument about the decisions of members of congress to seek re-election.

Specifically, the Fugitive Slave Act split Fillmore’s Whig party, he narrowly lost re-nomination, and the Whig defeat in the general election signaled its end as a national party. Hayes came to power through the Compromise of 1877, and strife over “Rutherfraud’s” ascendance may have spurred him to honor his pre-election pledge of serving only one term (of course, numerous candidates broke such promises). LBJ’s 1968 withdrawal during the nomination process may have been due to the Vietnam War—while he initially ran for a second full term, he withdrew after barely defeating anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary. Ford’s loss may have stemmed in part from his unpopular pardon of Nixon and a primary fight with Ronald Reagan.

Several former presidents sought non-consecutive terms (such as van Buren, Fillmore, Grant, and Theodore Roosevelt), but these do not factor into our analysis.

In part, the absence of autocorrelation arises because we code our dependent variables not based on candidate or party but incumbent. In a regression of our key run-win dependent variable on election-year GDP growth, the Durbin-Watson statistic is almost exactly 2, indicating no presence of autocorrelation at lag 1 in the residuals. The Breusch-Godfrey LM test for autocorrelation yields a p-value of 0.31 for the first lag and 0.10 for the second lag. In our analysis examining incumbent party vote share, we do detect autocorrelation but it's only clearly present post-World War II.

We code the Quasi-War as unpopular in the 1800 election; the War of 1812 as unpopular in 1812 but popular in 1816; the Mexican–American War as popular in 1848; the Civil War as popular in 1864; the Spanish-American war as popular in 1900; World War I as unpopular in 1920; World War II as popular in 1944; the Korean War as unpopular in 1952; the Vietnam War as unpopular in 1968 but popular in 1972; and the Iraq war as unpopular in 2004.

We tried an alternative version coding 1800, 1812, 1848, 1972, and 2004 to neither popular nor unpopular, a more conservative coding. We also tried a liberal version where we coded 1916, 1940, and 1964 as popular (popular for staying out in 1916 and 1940 and for responding to an alleged attack in 1964).

The control variables generally have their expected effects. Imminent death decreases the probability of running again and winning. War has the opposite of the expected effect on running again. The party’s years in power has a negative effect on winning. Further analysis, however, reveals that this effect is absent in America’s first century (SI section 2). Party dominance weakly predicts running again, but better predicts winning. The presence of multiple candidates understandably hurts the incumbent’s chances of winning, although this may just represent a post-treatment consequence of a weak incumbent.

Some states held popular votes before 1824, but the reporting was inconsistent, with totals for individual electors and totals across the candidates' electors sometimes failing to match.

Another possible explanation for the weak relationship between election-year growth and incumbent vote percent is that the composition of the United States changed considerably across elections as states joined the union, making election to election comparisons of incumbent vote percent noisy. To explore this possibility, we recalculated incumbent vote percent only among states in the union in the prior election. We also explored analyzing change in incumbent party and incumbent candidate vote share by controlling for lagged incumbent vote, again focusing only on states in the union in subsequent elections. These analyses, however, yielded very similar estimates to those in Table 3.

References

Achen, C. H. (2016). A baseline for incumbency effects. In A. S. Gerber & E. Schickler (Eds.), Governing in a polarized age: Elections, parties, and political representation in America (pp. 90–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government.s Princeton studies in political behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Anderson, C. J. (2007). The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.050806.155344.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-i Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of Political Economy, 100(2), 223–251. https://doi.org/10.1086/261816.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2018). “Industrial Production Index, 1919–2018.” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2018. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/INDPRO.

Bolt, J., Inklaar, R., de Jong, H., & van Zanden J. L. (2018). Maddison Project Database: ‘Rebasing “Maddison”: New income comparisons and the shape of long-run economic development.

Coyle, D. (2015). GDP: A brief but affectionate history—Revised and expanded edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dalton, R. J. (1984). Cognitive mobilization and partisan dealignment in advanced industrial democracies. The Journal of Politics, 46(1), 264–284. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130444.

Dassonneville, R., & Lewis-Beck, M. (2017). Rules, institutions and the economic vote: Clarifying clarity of responsibility. West European Politics, 40(3), 534–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1266186.

Dassonneville, R., & Lewis-Beck, M. (2019). A changing economic vote in Western Europe? Long-term vs. short-term forces. European Political Science Review, 11(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000231.

Davis, J. H. (2004). An annual index of U. S. industrial production, 1790–1915. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1177–1215.

Davis, J. H. (2006). An improved annual chronology of U.S. Business Cycles since the 1790s. The Journal of Economic History, 66(1), 103–121.

Duch, R. M. (2001). A developmental model of heterogeneous economic voting in new democracies. American Political Science Review, 95(4), 895–910. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400400080.

Duch, R. M., & Stevenson, R. T. (2008). The economic vote: How political and economic institutions condition election results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, R. S. (1989). Economic conditions and the presidential vote. The American Political Science Review, 83(2), 567–573. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962406.

Fair, R. C. (1996). The effect of economic events on votes for president: 1992 update. Political Behavior, 18(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01498787.

Flood, C. B. (2009). 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History (1st Simon & Schuster hardcover). New York: Simon & Schuster.

Healy, A., & Lenz, G. (2014). Substituting the end for the whole: Why voters respond primarily to the election-year economy. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12053.

Healy, A., & Malhotra, N. (2013). Retrospective voting reconsidered. Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-212920.

Hellwig, T., & Samuels, D. (2007). Voting in open economies: The electoral consequences of globalization. Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 283–306.

Hibbs, D.A. 1989. The American Political Economy. Harvard University Press.

Impartial Observer. 1808, December 3, 1808.

Johnston, L., & Williamson, S. H. (2018). Measuring worth—Gross domestic product—What was the U.S. GDP then? 2018. https://www.measuringworth.com/usgdp/.

Jacobson, G. C., & Kellner, S. (1981). Strategy and choice in congressional elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kiewiet, D. R., & Udell, M. (1998). Twenty-five years after Kramer: An assessment of economic retrospective voting based upon improved estimates of income and unemployment. Economics & Politics, 10(3), 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0343.00045.

Kramer, G. H. (1971). Short-term fluctuations in U.S. voting behavior, 1896–1964. The American Political Science Review, 65(1), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955049.

Krause, G. A. (1997). Voters, information heterogeneity, and the dynamics of aggregate economic expectations. American Journal of Political Science, 41(4), 1170–1200. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960486.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. (1988). Economics and elections: The major western democracies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Ratto, M. C. (2013). Economic voting in Latin America: A general model. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.023.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 183–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183.

Lynch, G. P. (1999). Presidential elections and the economy 1872 to 1996: The Times they are a ’Changin or the Song Remains the Same? Political Research Quarterly, 52(4), 825–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299905200408.

Mann, B. H. (2002). Republic of debtors: Bankruptcy in the age of American independence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Markus, G. B. (1992). The impact of personal and national economic conditions on presidential voting, 1956–1988. American Journal of Political Science, 36(3), 829–834. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111594.

McCusker, J. J. (2000). Estimating early American gross domestic product. Historical Methods, 33(3), 155–162.

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2018). US business cycle expansions and contractions. 2018. http://www.nber.org/cycles.html.

New-Hampshire Gazette. 1840, August 4, 1840.

Norpoth, H. (2004). Bush v. Gore: The recount of economic voting. In H. F. Weisberg & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Models of voting in presidential elections. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Powell, G. B., & Whitten, G. D. (1993). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 391–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111378.

Shafer, R. G. (2016). The Carnival Campaign: How the Rollicking 1840 Campaign of “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” changed presidential elections forever. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press.

Singer, M. M., & Carlin, R. E. (2013). Context counts: The election cycle, development, and the nature of economic voting. The Journal of Politics, 75(3), 730–742. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000467.

The Balance, and Columbian Repository. 1804. “Editorial,” September 25, 1804.

The Pittsfield Sun. 1840, November 5, 1840.

Thorp, W. L., & Thorp, H. E. (1926). Business annals: United States, England, France, Germany, Austria, Russia, Sweden, Netherlands, Italy, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, Australia, India, Japan, China. Publications of the National Bureau of Economic Research, no. 8. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Tufte, E. R. (1980). Political control of the economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Vavreck, L. (2009). The message matters: The economy and presidential campaigns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wetherell, C. (1986). The log percent (L%): An absolute measure of relative change. Historical Methods, 19(1), 25–26.

Weekly Aurora. (1816). National Economy Banking No. IV, January 30, 1816, VI:51 edition.

Wlezien, C. (2015). The myopic voter? The economy and US presidential elections. Electoral Studies, 39, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.03.010.

Woolley, J. T., & Peters, G. (2020). The American Presidency Project [online]. Santa Barbara, CA. Available from the World Wide Web: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=9259.

Zaller, J. (2004). Floating voters in U.S. presidential elections, 1948–2000. In W. E. Saris & P. M. Sniderman (Eds.), Studied in public opinion: attitudes, nonattitudes, measurement error, and change. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guntermann, E., Lenz, G.S. & Myers, J.R. The Impact of the Economy on Presidential Elections Throughout US History. Polit Behav 43, 837–857 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09677-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09677-y