Abstract

Background

People who are homeless have a higher burden of illness and higher rates of hospital admission and readmission compared to the general population. Identifying the factors associated with hospital readmission could help healthcare providers and policymakers improve post-discharge care for homeless patients.

Objective

To identify factors associated with hospital readmission within 90 days of discharge from a general internal medicine unit among patients experiencing homelessness.

Design

This prospective observational study was conducted at an urban academic teaching hospital in Toronto, Canada. Interviewer-administered questionnaires and chart reviews were completed to assess medical, social, processes of care, and hospitalization data. Multivariable logistic regression with backward selection was used to identify factors associated with a subsequent readmission and estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Participants

Adults (N = 129) who were admitted to the general internal medicine service between November 2017 and November 2018 and who were homeless at the time of admission.

Main Measures

Unplanned all-cause readmission to the study hospital within 90 days of discharge.

Key Results

Thirty-five of 129 participants (27.1%) were readmitted within 90 days of discharge. Factors associated with lower odds of readmission included having an active case manager (adjusted odds ratios [aOR]: 0.31, 95% CI, 0.13–0.76), having informal support such as friends and family (aOR: 0.25, 95% CI, 0.08–0.78), and sending a copy of the patient’s discharge plan to a primary care physician who had cared for the patient within the last year (aOR: 0.44, 95% CI, 0.17–1.16). A higher number of medications prescribed at discharge was associated with higher odds of readmission (aOR: 1.12, 95% CI, 1.02–1.23).

Conclusion

Interventions to reduce hospital readmission for people who are homeless should evaluate tailored discharge planning and dedicated resources to support implementation of these plans in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

More than 35,000 people experience homelessness in Canada every night,1 and in the USA, over half a million individuals are homeless at any given time.2 People who are homeless have a high prevalence of acute and chronic illness3,4,5,6,7 and often experience substantial barriers to obtaining healthcare in the community. Challenges described in the literature include lack of a regular care provider, costs associated with obtaining healthcare, and competing priorities such as housing instability and food insecurity.8,9,10,11,12,13,14 As a result, homeless individuals have high levels of unmet healthcare needs15, 16 and higher rates of hospital admission and readmission compared to the general population.17,18,19,20

Readmission to hospital has been a prominent area of focus for healthcare research to improve quality of care and reduce costs for health systems, but relatively few studies have examined readmissions in homeless populations. While the general Canadian and US populations have 30-day readmission rates of 9.4% and 13.9% respectively,21, 22 the 30-day readmission rate among homeless populations ranges from approximately 20 to 50%.18,19,20, 23,24,25,26 Ninety-day readmission rates have been found to be within a similar range.18, 27, 28 Identification of the factors associated with readmission among patients experiencing homelessness could provide insight for healthcare providers and policymakers to better support the transition from hospital to community for these individuals.

Factors associated with 90- or 30-day readmission in the homeless population include race or ethnicity, prior hospital and healthcare service usage, discharge location, and having a primary care provider, as well as hospitalization characteristics such as particular discharge diagnoses, length of stay, and leaving the hospital against medical advice (AMA).19, 23,24,25, 27, 28 In contrast, there is no clear evidence to suggest that age, sex or gender, alcohol or drug use, mental health-related conditions, and illness burden or number of chronic diseases are associated with higher readmission rates.19, 23,24,25, 27,28,29 Some studies have suggested that social support30,31,32,33,34,35 and case management36,37,38 improve health outcomes in this population, while having a primary care provider may benefit healthcare transitions;19, 24, 25, 27 accordingly, these factors need further exploration.

This study sought to identify the factors associated with hospital readmission within 90 days of discharge from a general internal medicine unit among patients experiencing homelessness. Informed by the existing literature, demographic, medical, social, and processes of care data were obtained in order to evaluate a range of factors potentially associated with readmission.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

This prospective cohort study was conducted at an urban academic teaching hospital in Toronto, Canada. Participants were recruited between November 2017 and November 2018. Eligible participants included individuals 18 years or older, admitted to the general internal medicine service, and who were homeless at the time of admission. Homelessness was defined as being unsheltered (living on the streets or in places not intended for human habitation), emergency sheltered (staying in overnight shelters), or provisionally accommodated (staying in temporary accommodation which lacks security of tenure).39 Individuals were excluded if they did not wish to participate, were too unwell to participate or incapable of providing consent, or were unable to communicate in English.

Research staff identified potentially eligible participants through daily review of the general internal medicine patient census, which includes place of residence. Once identified, a member of the patient’s circle of care obtained permission from the patient to introduce the research staff using a short script. Research staff confirmed eligibility, explained the study, and obtained written informed consent.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was an unplanned hospital readmission within 90 days of discharge. A period of 90 days was chosen to account for the complex health and social challenges that homeless people face following hospitalization, which may last longer than a duration of 30 days. Research staff tracked the discharge and readmission dates of participants by regularly reviewing the individual’s hospital record. If a participant was readmitted more than once during the 90-day follow-up period, only the first readmission was included in this analysis. Admissions to other hospitals were not systematically captured for all participants.

Data Collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire based on the Kaiser Permanente All-Cause Readmissions Diagnostic Tool. This questionnaire consisted of a patient survey and a structured hospital chart review of the electronic patient record for each admission and discharge. The patient survey was administered by research staff during the baseline interview to determine the patient’s self-reported race, socioeconomic status, history of homelessness, alcohol and drug use, and medical and social supports in the community. Participants were considered to be receiving active case management if they had engaged with their case manager in the past 60 days. In a separate survey item, participants were prompted to answer the open-ended question, “When you are discharged from here, what supports (people or services) can you rely on?” to describe their social support. Answers from this question were subsequently categorized into “formal supports” (e.g., medical professionals, social service workers) and “informal supports” (e.g., family, friends, religious groups, volunteer groups). Data on additional demographic factors including age and gender, prior healthcare usage, and current hospitalization characteristics such as length of stay, discharge diagnoses, and comorbidities used in the Charlson Comorbidity Index40 were collected from the chart review. Measures of care transitions were noted, including written documentation of instructions for the patient to follow if their condition worsened and communication of the patient discharge summary to an active primary care provider, defined as a provider who had cared for the patient in the past year, or was referred to the patient at the time of discharge.

Statistical Analysis

The 90-day readmission rate and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated as the proportion of index admissions which resulted in a readmission post-discharge. Other reported descriptive statistics included the 30-day readmission rate, median (interquartile range) time to readmission, and the distribution of the number of readmissions in the 90-day post-discharge period. The proportion of patients who were readmitted for an identical diagnosis as their initial admission was also calculated.

Potential factors associated with readmission within 90 days of discharge were selected based on the literature on readmission in similar populations and the clinical experience of the research team.5, 19, 23,24,25, 27, 28, 30, 41,42,43 The demographic variables of age, gender, and self-identified race were also considered.

Logistic regression models were fit to the data to estimate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Backward selection in the multivariable model was used to retain variables with p values ≤ 0.15. Adequacy of the models was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Model discrimination was evaluated using the area under the curve. All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was defined for p values less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics and Readmission Rate

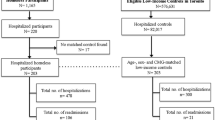

Between November 2017 and November 2018, a total of 206 eligible patients were identified. Of these patients, 55 were not able to be recruited prior to discharge, most often due to severe illness or a brief hospitalization (both admission and discharge occurring outside of study recruitment hours of 9 AM to 4 PM on weekdays). Two patients died before study staff could make contact and 18 declined to participate. In total, 133 patients were enrolled in this study. Four patients were subsequently excluded from this analysis: 2 patients were found to be housed and therefore ineligible, and 2 patients died during their admission. Thus, the total number of participants included in this analysis was 129.

The characteristics of participants and their hospitalizations are shown in Table 1. Within 90 days after discharge, 35 patients (27.1%, 95% CI, 19.5–34.8) had an unplanned all-cause hospital readmission. Among those who had a readmission during this period, 26 patients (74.3%) were readmitted once, 8 (22.9%) were readmitted twice, and 1 (2.9% ) was readmitted 3 times. The median time to readmission was 20 days (interquartile range 7–59 days). Roughly one-third of patients (34.3%) were readmitted for an identical diagnosis as their initial admission (Supplemental Table 1). The readmission rate within 30 days was 17.1% (95% CI, 10.6–23.5).

Factors Associated with Readmission

The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 2.

In the multivariable model, four variables were found to be independently associated with readmission. Having a case manager or social worker (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.31, 95% CI, 0.13–0.76) or having at least one informal support (aOR: 0.25, 95% CI, 0.08–0.78) was associated with significantly lower odds of readmission 90 days post-discharge. For every additional medication prescribed at discharge, the odds of readmission increased by 12% (aOR: 1.12, 95% CI, 1.02–1.23). Sending the discharge plan to an active primary care physician was associated with a 56% reduction in the odds of readmission (aOR: 0.44, 95% CI, 0.17–1.16) but this finding did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.10). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was 0.48 and the area under the ROC curve was 0.75.

DISCUSSION

In a group of people experiencing homelessness who were admitted to a general internal medicine service, we found that one-quarter (27.1%) were readmitted within 90 days. Three studies looking at 90-day readmission rates in the homeless population reported rates of 21.2%,28 24.5%,18 and 34.3%.27 Additional studies focused on a shorter period of 30 days: our observed 30-day readmission rate of 17.1% is at the lower end of the rates reported in the literature, which are between 17.7 and 50.8%.19, 20, 23,24,25,26,27 Study differences such as variation in the definition of homelessness, the types of readmissions included, methods of data collection, and availability of outpatient services may account for the discrepancies between reported rates in both 90- and 30-day time periods. Notably, two retrospective analyses of administrative health data in similar Canadian populations reported 30-day readmission rates of 22.2% and 22.6%.19, 27 While we captured readmissions to a single institution, these groups included readmissions to all of the hospitals in the region through administrative data review. Although our study hospital provides a large proportion of inpatient care for people experiencing homelessness in our community, our analysis likely missed a subset of admissions to 3 nearby hospitals that may account for this difference.

Our study showed that for each additional medication a patient was prescribed at discharge, their odds of readmission increased by 12% (95% CI, 2–23). Two other study variables, the Charlson Comorbidity Index and discharge diagnoses, were also indicators of a patient’s burden and severity of disease; however, these variables were not associated with a change in odds of readmission. Thus, a higher number of medications prescribed may signify a more challenging treatment regimen in addition to increased illness complexity. Homeless patients face multiple structural and personal barriers to obtaining and adhering to medication such as costs, limited access to primary care for prescription renewals, few options to safely store medication, concurrent alcohol or substance use, and insufficient support to self-manage medication administration.44,45,46 Given these barriers, a lack of appropriate post-discharge support to adhere to complex treatment plans may lead to higher odds of readmission.

Our analyses suggest that non-medical support post-discharge may reduce the odds of readmission. Consistent with existing literature, self-reported informal social support after discharge was a significant protective factor in our model.30,31,32,33 Previous studies have noted that supportive relationships can help patients transition from hospital by providing emotional, financial, and tangible support such as providing transportation to appointments. While we used an open-ended prompt for this outcome, in future studies, nuanced questioning on the size and involvement of patients’ support networks would enrich analyses on the impact of social support on readmission.

Having a case manager or social worker also reduced the odds of readmission in our analysis.36 However, a recent systematic review noted substantial variation in the effects of different case management models for people experiencing homelessness or who are vulnerably housed.37 Though this review did not explore hospital readmission as an outcome, some assertive community treatment and critical time intervention programs were found to reduce the amount of time hospitalized. Studies examining standard and intensive case management models did not report reductions for this outcome. Our results, taken with this finding, point to the potential benefits of case management and the necessity of determining the best model of support to positively affect health and hospitalization.

Patients whose discharge plan was communicated with their active primary care provider were less than half as likely to be readmitted than those whose discharge summary was not sent to an outpatient provider. Though we did not systematically ascertain if all participants had received post-discharge support in the community, our finding shows a potential benefit to communication between the hospital and the patient’s primary care provider. In a similar finding, Racine et al. reported that having a primary care provider at the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program reduced the odds of patient readmission.24 Other work on the continuity of care between hospital and outpatient services has not suggested the same direction and degree of association, however. Doran et al. found that having a follow-up appointment made for the patient at the time of discharge did not affect patients’ likelihood of readmission; however, the authors note that most participants did not attend their appointment.25 Furthermore, Saab et al. determined that having a primary care provider actually increases the odds of readmission.19 This association may be related to the study design: hospitalizations were captured in administrative data up to 5 years after primary care data was obtained through interviewer-administered questionnaires. The authors could not therefore ascertain if the participant was connected to a primary care provider at the time of hospitalization or readmission, nor if the patient attended an appointment. Currie et al. found that using outpatient services within 7 days of discharge was not protective of 60-day readmission; this study cohort was defined as having mental illness, and the majority of hospitalizations were psychiatric, which differs from ours and other studies.27 Thus, the role of communication between hospital-based and primary care providers to improve post-discharge care for patients experiencing homelessness merits further exploration.

Previous research has suggested that the challenges of discharge planning can be attenuated by discharging patients to respite care, medical facilities, and temporary housing24, 25, 28, 47 though we did not find an association between discharge location and readmission. Respite centers, with centralized medical and social services, have been found to be particularly useful for homeless individuals.24, 28, 47 We did not examine respite care use specifically due to the very small number of patients who were discharged to this service, though this variable would be of interest in future studies.

Literature suggests leaving against medical advice may be associated with a higher odds of readmission in homeless patients.19, 23,24,25, 42, 48 Our study found that 14.3% of readmitted patients (n = 5) left AMA during their initial hospitalization compared to 10.6% of non-readmitted participants (n = 10). Saab et al., also in Toronto, found a significant difference in the self-discharge rates between readmitted patients (14.8%) and non-readmitted patients (7.8%).19 Though our rates are comparable with Saab et al., our study may have lacked the power to show statistical significance in this finding. Additionally, our longer follow-up period of 90 days may have diluted the effect of leaving AMA, which has been suggested to be concentrated within the first 1–2 weeks of discharge.48,49,50 The overall percentage of patients who left AMA in our study is exceptionally high compared to that of the general public, for which only 1–2% of all admissions to inpatient acute care end in self-discharge.51, 52 This difference may speak to the unique needs of patients experiencing homelessness who may require tailored, in-hospital services to support and assist the completion of their inpatient stay.

We included mental health and substance use variables because of their association with higher readmission rates in comparable low-income populations53 and their prevalence within the homeless population,6 but we did not find an association between readmission and either variable. In 5 similar studies examining readmission rates in the homeless population, these factors were also not found to be associated.19, 24, 25, 27, 28

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study used patient surveys as well as administrative data to capture a range of variables. This methodology provided detailed information on participants’ living situations as well as their connection to social support and care providers, which is not generally available through solely administrative sources. Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. Patients were recruited during their hospital stay; therefore, patients who were too ill to consent and those who left before they could be approached by study staff were not included. It is therefore likely we missed patients who had the highest and lowest acuity of illness and as such, findings may not be representative of all admissions. Furthermore, all participants were enrolled at a single hospital, and readmissions were ascertained only at that hospital. Given the mobility of individuals experiencing homelessness, it is likely that our readmission rate is an underestimate. Lastly, our relatively small sample size of 129 patients may have limited our ability to analyze certain variables, such as the effect of leaving against medical advice.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the 90-day readmission rate among homeless patients was substantially higher than that observed in the general population. Identifying the factors associated with readmission among homeless individuals can help meet the unique needs of patients while potentially reducing healthcare spending. We found that case management, informal support post-discharge, and increased communication between the hospital and the patient’s primary care provider were potentially protective against readmission, while an increased number of medications raised the odds of readmission. Our findings emphasize the necessity of both developing tailored discharge plans for people experiencing homelessness and bolstering resources to assist in the implementation of these plans. Interventions to address the transition from hospital to community for people who are homeless should evaluate whether focused support in these areas is effective.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gaetz S, Erin D, Richter T, Redman M. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2016.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington, DC; 2020.

Schanzer B, Dominguez B, Shrout PE, Caton CL. Homelessness, health status, and health care use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):464-9.

Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, Geddes J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(12):e225.

Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529-1540.

Hwang S. Mental illness and mortality among homeless people. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(2):81-2.

Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10117):241-250.

Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71-7.

Lim YW, Andersen R, Leake B, Cunningham W, Gelberg L. How accessible is medical care for homeless women? Med Care. 2002;40(6):510-20.

Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200-6.

Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217-20.

Rosenheck R, Lam JA. Client and site characteristics as barriers to service use by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(3):387-90.

Omerov P, Craftman AG, Mattsson E, Klarare A. Homeless persons’ experiences of health- and social care: A systematic integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(1):1-11.

Greysen SR, Allen R, Lucas GI, Wang EA, Rosenthal MS. Understanding transitions in care from hospital to homeless shelter: a mixed-methods, community-based participatory approach. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1484-91.

Kertesz SG, McNeil W, Cash JJ, et al. Unmet need for medical care and safety net accessibility among Birmingham’s homeless. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):33-45.

Argintaru N, Chambers C, Gogosis E, et al. A cross-sectional observational study of unmet health needs among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:577.

Buck DS, Brown CA, Mortensen K, Riggs JW, Franzini L. Comparing homeless and domiciled patients’ utilization of the Harris County, Texas public hospital system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(4):1660-70.

Khatana SAM, Wadhera RK, Choi E, et al. Association of Homelessness with Hospital Readmissions-an Analysis of Three Large States. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2576-2583.

Saab D, Nisenbaum R, Dhalla I, Hwang SW. Hospital Readmissions in a Community-based Sample of Homeless Adults: a Matched-cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1011-8.

Miyawaki A, Hasegawa K, Figueroa JF, Tsugawa Y. Hospital Readmission and Emergency Department Revisits of Homeless Patients Treated at Homeless-Serving Hospitals in the USA: Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2560-2568.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Your Health System: All Patients Readmitted to Hospital. https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/inbrief.#!/indicators/006/all-patients-readmitted-to-hospital/;mapC1;mapLevel2;provinceC5001;trend(C1,C5001);/. Accessed February 19, 2020.

Bailey MK, Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Characteristics of 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Readmissions, 2010-2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #248. 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp. Accessed February 19, 2020.

Dirmyer VF. The frequent fliers of New Mexico: hospital readmissions among the homeless population. Soc Work Public Health. 2016;31(4):288-98.

Racine MW, Munson D, Gaeta JM, Baggett TP. Thirty-Day Hospital Readmission Among Homeless Individuals With Medicaid in Massachusetts. Med Care. 2020;58(1):27-32.

Doran KM, Ragins KT, Iacomacci AL, Cunningham A, Jubanyik KJ, Jenq GY. The revolving hospital door: hospital readmissions among patients who are homeless. Med Care. 2013;51(9):767-73.

Rosendale N, Guterman EL, Betjemann JP, Josephson SA, Douglas VC. Hospital admission and readmission among homeless patients with neurologic disease. Neurology. 2019;92(24):e2822-e2831.

Currie LB, Patterson ML, Moniruzzaman A, McCandless LC, Somers JM. Continuity of care among people experiencing homelessness and mental illness: does community follow-up reduce rehospitalization? Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3400-3415.

Kertesz SG, Posner MA, O’Connell JJ, et al. Post-hospital medical respite care and hospital readmission of homeless persons. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(2):129-42.

Cheung A, Somers JM, Moniruzzaman A, et al. Emergency department use and hospitalizations among homeless adults with substance dependence and mental disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10:17.

Chambers C, Katic M, Chiu S, et al. Predictors of medical or surgical and psychiatric hospitalizations among a population-based cohort of homeless adults. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S380-8.

Hwang SW, Kirst MJ, Chiu S, et al. Multidimensional social support and the health of homeless individuals. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):791-803.

Lam JA, Rosenheck R. Social support and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):13-28.

Toro PA, Tulloch E, Ouellette N. Stress, social support, and outcomes in two probability samples of homeless adults. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(4):483-498.

Johnstone M, Parsell C, Jetten J, Dingle G, Walter Z. Breaking the cycle of homelessness: housing stability and social support as predictors of long-term well-being. Hous Stud. 2015;31(4):410-426.

Riley ED, Neilands TB, Moore K, Cohen J, Bangsberg DR, Havlir D. Social, structural and behavioral determinants of overall health status in a cohort of homeless and unstably housed HIV-infected men. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35207.

Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Lambert M, Dufour I, Krieg C. Effectiveness of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012353.

Ponka D, Agbata E, Kendall C, et al. The effectiveness of case management interventions for the homeless, vulnerably housed and persons with lived experience: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;5(4): e0230896.

Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771-8.

Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, et al. Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2012.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-82.

Russolillo A, Moniruzzaman A, Parpouchi M, Currie LB, Somers JM. A 10-year retrospective analysis of hospital admissions and length of stay among a cohort of homeless adults in Vancouver, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:60.

White BM, Ellis C, Jr, Simpson KN. Preventable hospital admissions among the homeless in California: a retrospective analysis of care for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:511.

Small LF. Determinants of physician utilization, emergency room use, and hospitalizations among populations with multiple health vulnerabilities. Health (London). 2011;15(5):491-516.

Law MR, Cheng L, Dhalla IA, Heard D, Morgan SG. The effect of cost on adherence to prescription medications in Canada. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):297-302.

Nyamathi A, Shuler P. Factors affecting prescribed medication compliance of the urban homeless adult. Nurse Pract. 1989;14(8):47-8, 51-2, 54.

Hunter CE, Palepu A, Farrell S, Gogosis E, O’Brien K, Hwang SW. Barriers to prescription medication adherence among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(3):154-61.

Buchanan D, Doblin B, Sai T, Garcia P. The effects of respite care for homeless patients: a cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1278-81.

Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459.

Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003;168(4):417-20.

Garland A, Ramsey CD, Fransoo R, et al. Rates of readmission and death associated with leaving hospital against medical advice: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2013;185(14):1207-14.

Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-9.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Leaving Against Medical Advice: Characteristics Associated With Self-Discharge. 2013. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/LAMA_aib_oct012013_en.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2020.

Becker MA, Boaz TL, Andel R, Hafner S. Risk of early rehospitalization for non-behavioral health conditions among adult Medicaid beneficiaries with severe mental illness or substance use disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(1):113-121.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants of this study for sharing their experiences, information, and their time with us; the staff of St. Michael’s Hospital general internal medicine ward for their assistance with recruitment; Dr. Yayi Huang for her contribution to developing the study protocol; and the Survey Research Unit at the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, in particular Paula Smith and Sonia Zawitkowski, who coordinated and administered questionnaires with patients and completed patient chart reviews.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital (now Unity Health Toronto) Research Ethics Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 39 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, A., Pridham, K.F., Nisenbaum, R. et al. Factors Associated with Readmission Among General Internal Medicine Patients Experiencing Homelessness. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1944–1950 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06483-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06483-w